Ornithology at the University of Kansasl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Phylogenetic Position of Ambiortus: Comparison with Other Mesozoic Birds from Asia1 J

ISSN 00310301, Paleontological Journal, 2013, Vol. 47, No. 11, pp. 1270–1281. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2013. The Phylogenetic Position of Ambiortus: Comparison with Other Mesozoic Birds from Asia1 J. K. O’Connora and N. V. Zelenkovb aKey Laboratory of Evolution and Systematics, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, 142 Xizhimenwai Dajie, Beijing China 10044 bBorissiak Paleontological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Profsoyuznaya ul. 123, Moscow, 117997 Russia email: [email protected], [email protected] Received August 6, 2012 Abstract—Since the last description of the ornithurine bird Ambiortus dementjevi from Mongolia, a wealth of Early Cretaceous birds have been discovered in China. Here we provide a detailed comparison of the anatomy of Ambiortus relative to other known Early Cretaceous ornithuromorphs from the Chinese Jehol Group and Xiagou Formation. We include new information on Ambiortus from a previously undescribed slab preserving part of the sternum. Ambiortus is superficially similar to Gansus yumenensis from the Aptian Xiagou Forma tion but shares more morphological features with Yixianornis grabaui (Ornithuromorpha: Songlingorni thidae) from the Jiufotang Formation of the Jehol Group. In general, the mosaic pattern of character distri bution among early ornithuromorph taxa does not reveal obvious relationships between taxa. Ambiortus was placed in a large phylogenetic analysis of Mesozoic birds, which confirms morphological observations and places Ambiortus in a polytomy with Yixianornis and Gansus. Keywords: Ornithuromorpha, Ambiortus, osteology, phylogeny, Early Cretaceous, Mongolia DOI: 10.1134/S0031030113110063 1 INTRODUCTION and articulated partial skeleton, preserving several cervi cal and thoracic vertebrae, and parts of the left thoracic Ambiortus dementjevi Kurochkin, 1982 was one of girdle and wing (specimen PIN, nos. -

Current Perspectives on the Evolution of Birds

Contributions to Zoology, 77 (2) 109-116 (2008) Current perspectives on the evolution of birds Per G.P. Ericson Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 50007, SE-10405 Stockholm, Sweden, [email protected] Key words: Aves, phylogeny, systematics, fossils, DNA, genetics, biogeography Contents (cf. Göhlich and Chiappe, 2006), making feathers a plesiomorphy in birds. Indeed, only three synapo- Systematic relationships ........................................................ 109 morphies have been proposed for Aves (Chiappe, Genome characteristics ......................................................... 111 2002), although monophyly is never seriously ques- A comparison with previous classifications ...................... 112 Character evolution ............................................................... 113 tioned: 1) the caudal margin of naris nearly reaching Evolutionary trends ............................................................... 113 or overlapping the rostral border of the antorbital Biogeography and biodiversity ............................................ 113 fossa (in the primitive condition the caudal margin Differentiation and speciation ............................................. 114 of naris is farther rostral than the rostral border of Acknowledgements ................................................................ 115 the antorbital fossa), 2) scapula with a prominent References ................................................................................ 115 acromion, -

Breeding Ecology and Extinction of the Great Auk (Pinguinus Impennis): Anecdotal Evidence and Conjectures

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VOL. 101 JANUARY1984 No. 1 BREEDING ECOLOGY AND EXTINCTION OF THE GREAT AUK (PINGUINUS IMPENNIS): ANECDOTAL EVIDENCE AND CONJECTURES SVEN-AXEL BENGTSON Museumof Zoology,University of Lund,Helgonavi•en 3, S-223 62 Lund,Sweden The Garefowl, or Great Auk (Pinguinusimpen- Thus, the sad history of this grand, flightless nis)(Frontispiece), met its final fate in 1844 (or auk has received considerable attention and has shortly thereafter), before anyone versed in often been told. Still, the final episodeof the natural history had endeavoured to study the epilogue deservesto be repeated.Probably al- living bird in the field. In fact, no naturalist ready before the beginning of the 19th centu- ever reported having met with a Great Auk in ry, the GreatAuk wasgone on the westernside its natural environment, although specimens of the Atlantic, and in Europe it was on the were occasionallykept in captivity for short verge of extinction. The last few pairs were periods of time. For instance, the Danish nat- known to breed on some isolated skerries and uralist Ole Worm (Worm 1655) obtained a live rocks off the southwesternpeninsula of Ice- bird from the Faroe Islands and observed it for land. One day between 2 and 5 June 1844, a several months, and Fleming (1824) had the party of Icelanderslanded on Eldey, a stackof opportunity to study a Great Auk that had been volcanic tuff with precipitouscliffs and a flat caught on the island of St. Kilda, Outer Heb- top, now harbouring one of the largestsgan- rides, in 1821. nettles in the world. -

Selected Bibliography of American History Through Biography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 763 SO 007 145 AUTHOR Fustukjian, Samuel, Comp. TITLE Selected Bibliography of American History through Biography. PUB DATE Aug 71 NOTE 101p.; Represents holdings in the Penfold Library, State University of New York, College at Oswego EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$5.40 DESCRIPTORS *American Culture; *American Studies; Architects; Bibliographies; *Biographies; Business; Education; Lawyers; Literature; Medicine; Military Personnel; Politics; Presidents; Religion; Scientists; Social Work; *United States History ABSTRACT The books included in this bibliography were written by or about notable Americans from the 16th century to the present and were selected from the moldings of the Penfield Library, State University of New York, Oswego, on the basis of the individual's contribution in his field. The division irto subject groups is borrowed from the biographical section of the "Encyclopedia of American History" with the addition of "Presidents" and includes fields in science, social science, arts and humanities, and public life. A person versatile in more than one field is categorized under the field which reflects his greatest achievement. Scientists who were more effective in the diffusion of knowledge than in original and creative work, appear in the tables as "Educators." Each bibliographic entry includes author, title, publisher, place and data of publication, and Library of Congress classification. An index of names and list of selected reference tools containing biographies concludes the bibliography. (JH) U S DEPARTMENT Of NIA1.114, EDUCATIONaWELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OP EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED ExAC ICY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIGIN ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILYREPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTEOF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY PREFACE American History, through biograRhies is a bibliography of books written about 1, notable Americans, found in Penfield Library at S.U.N.Y. -

Birdobserver17.4 Page183-188 an Honor Without Profit Richard K

AN HONOR WITHOUT PROFIT by Richard K. Walton eponymy n The derivation of a name of a city, country, era, institution, or other place or thing from the name of a person. Gruson in his Words for Birds gives seven categories for the origins of common bird names: appearance (Black-capped Chickadee), eponymy (Henslow’s Sparrow), echoics (Whooping Crane), habitat (Marsh Wren), behavior (woodpecker), food (oystercatcher), and region (California Condor). The second category comprises people and places memorialized in bird names. Many of our most famous ornithologists as well as a fair number of obscure friends and relations have been so honored. A majority of these names were given during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the pioneering era of North American ornithology. While some of these tributes are kept alive in our everyday birding language, others have slipped into oblivion. Recognition or obscurity may ultimately hinge on the names we use for birds. There is no more famous name in the birding culture than that of John James Audubon. His epic The Birds of America was responsible for putting American science, art, and even literature on the international map. This work was created, produced, promoted, and sold largely by Audubon himself. In the years since his death in 1851, the Audubon legend has been the inspiration for a multitude of ornithological pursuits and causes, both professional and amateur. Audubon painted some five hundred birds in Birds of America and described these in his five-volume Ornithological Biographies. Many of the names given by Audubon honored men and women of his era. -

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber's Advocacy for Gender

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber’s Advocacy for Gender Equality in Ornithology TANJA HAMMEL Department of History, University of Basel This article explores parts of the first South African woman ornithologist’s life and work. It concerns itself with the micro-politics of Mary Elizabeth Barber’s knowledge of birds from the 1860s to the mid-1880s. Her work provides insight into contemporary scientific practices, particularly the importance of cross-cultural collaboration. I foreground how she cultivated a feminist Darwinism in which birds served as corroborative evidence for female selection and how she negotiated gender equality in her ornithological work. She did so by constructing local birdlife as a space of gender equality. While male ornithologists naturalised and reinvigorated Victorian gender roles in their descriptions and depictions of birds, she debunked them and stressed the absence of gendered spheres in bird life. She emphasised the female and male birds’ collaboration and gender equality that she missed in Victorian matrimony, an institution she harshly criticised. Reading her work against the background of her life story shows how her personal experiences as wife and mother as well as her observation of settler society informed her view on birds, and vice versa. Through birds she presented alternative relationships to matrimony. Her protection of insectivorous birds was at the same time an attempt to stress the need for a New Woman, an aspect that has hitherto been overlooked in studies of the transnational anti-plumage -

The Artist and the American Land

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1975 A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land Norman A. Geske Director at Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska- Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Geske, Norman A., "A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land" (1975). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 112. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/112 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME I is the book on which this exhibition is based: A Sense at Place The Artist and The American Land By Alan Gussow Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 79-154250 COVER: GUSSOW (DETAIL) "LOOSESTRIFE AND WINEBERRIES", 1965 Courtesy Washburn Galleries, Inc. New York a s~ns~ 0 ac~ THE ARTIST AND THE AMERICAN LAND VOLUME II [1 Lenders - Joslyn Art Museum ALLEN MEMORIAL ART MUSEUM, OBERLIN COLLEGE, Oberlin, Ohio MUNSON-WILLIAMS-PROCTOR INSTITUTE, Utica, New York AMERICAN REPUBLIC INSURANCE COMPANY, Des Moines, Iowa MUSEUM OF ART, THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY, University Park AMON CARTER MUSEUM, Fort Worth MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON MR. TOM BARTEK, Omaha NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, Washington, D.C. MR. THOMAS HART BENTON, Kansas City, Missouri NEBRASKA ART ASSOCIATION, Lincoln MR. AND MRS. EDMUND c. -

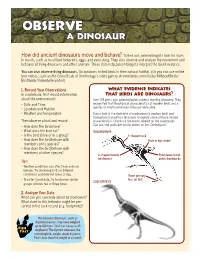

Observebserve a D Dinosaurinosaur

OOBSERVEBSERVE A DDINOSAURINOSAUR How did ancient dinosaurs move and behave? To fi nd out, paleontologists look for clues in fossils, such as fossilized footprints, eggs, and even dung. They also observe and analyze the movement and behavior of living dinosaurs and other animals. These data help paleontologists interpret the fossil evidence. You can also observe living dinosaurs. Go outdoors to fi nd birds in their natural habitat. (Or you can use online bird videos, such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s video gallery at www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/ BirdGuide/VideoGallery.html) 1. Record Your Observations What Evidence IndiCates In a notebook, fi rst record information That Birds Are Dinosaurs? about the environment: Over 125 years ago, paleontologists made a startling discovery. They • Date and Time recognized that the physical characteristics of modern birds and a • Location and Habitat species of small carnivorous dinosaur were alike. • Weather and temperature Take a look at the skeletons of roadrunner (a modern bird) and Coelophysis (an extinct dinosaur) to explore some of these shared Then observe a bird and record: characteristics. Check out the bones labeled on the roadrunner. • How does the bird move? Can you fi nd and label similar bones on the Coelophysis? • What does the bird eat? ROADRUNNER • Is the bird alone or in a group? S-shaped neck • How does the bird behave with Hole in hip socket members of its species? • How does the bird behave with members of other species? V-shaped furcula Pubis bone in hip (wishbone) points backwards Tips: • Weather conditions can affect how animals behave. -

Mammal Collections Accredited by the American Society of Mammalogists, Systematics Collections Committee

MAMMAL COLLECTIONS ACCREDITED BY THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF MAMMALOGISTS The collections on this list meet or exceed the basic curatorial standards established by the ASM Systematic Collections Committee (Appendix V). Collections are listed alphabetically by country, then province or state. Date of accreditation (and reaccreditation) are indicated. Year of Province Collection name and acronym accreditation or state ARGENTINA Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Colección de Mamíferos Lillo (CML) 1999 Tucumán CANADA Provincial Museum of Alberta (PMA) 1985 Alberta University of Alberta, Museum of Zoology (UAMZ) 1985 Alberta Royal British Columbia Museum (RBCM) 1976 British Columbia University of British Columbia, Cowan Vertebrate Museum (UBC) 1975 British Columbia Canadian Museum of Nature (CMN) 1975, 1987 Ontario Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) 1975, 1995 Ontario MEXICO Colección Nacional de Mamíferos, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (CNMA) 1975, 1983 Distrito Federal Centro de Investigaciones Biologicas del Noroeste (CIBNOR) 1999 Baja California Sur UNITED STATES University of Alaska Museum (UAM) 1975, 1983 Alaska University of Arizona, Collection of Mammals (UA) 1975, 1982 Arizona Arkansas State University, Collection of Recent Mammals (ASUMZ) 1976 Arkansas University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALRVC) 1977 Arkansas California Academy of Sciences (CAS) 1975 California California State University, Long Beach (CSULB) 1979, 1980 California Humboldt State University (HSU) 1984 California Natural History Museum of Los -

The Making of a Conservationist: Audubon's Ecological Memory

Journal of Ecocriticism 5(2) July 2013 The Making of a Conservationist: Audubon’s Ecological Memory Christian Knoeller (Purdue University)* Abstract While Audubon’s exploits as consummate artist, accomplished naturalist, and aspiring entrepreneur are widely recognized, his contributions as author and nascent conservationist remain less fully appreciated. Extensive travels observing and documenting wildlife as an artist-naturalist gave him a unique perspective on how human-induced changes to the landscape impacted wildlife. He lamented the reduction in range of many species and destruction of historic breeding grounds, as well as declining populations caused by overhunting and habitat loss. His understanding of changing landscapes might be thought of in terms of ecological memory reflected in his narratives of environmental history. He described the destruction of forests and fisheries as well as the shrinking ranges of species including several now extinct such as the Passenger Pigeon, Carolina Parakeet, and Ivory-billed Woodpecker. Quadrupeds of North America and the Missouri River Journals depict the impact of environmental destruction he witnessed taking place in the first half of the 19th century. While these later works suggest a growing interest in conservation, Audubon had already voiced such concerns frequently in his earlier writings. Copious journals kept throughout his career in the field on America’s westering frontier reveal a keen appreciation for environmental history. By the time he arrived on the Upper Missouri in 1843, his values regarding the preservation of wildlife and habitat had been forged by writing for decades about his observations in the wild. What began as a quest to celebrate the natural abundance of North America by documenting every species of bird took on new dimensions as he expressed increasing concerns about conservation having recognized the extent of development and declines in wildlife during his lifetime. -

Elan Margulies May 2007

William J. Hamilton, Jr. of Cornell, The Man and the Myth Honors Thesis Presented to the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Department of Natural Resources of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Research Honors Program by Elan Margulies May 2007 Under the Supervision of Professor Charles R. Smith 1 We refer to a certain elusive quality, which doubtless will be explored and exploited many, many years hence by some future biographer in a privately circulated volume entitled; William J. Hamilton, Jr. of Cornell, The Man and the Myth (Robert W. Harrington, Jr., Dear Bill Book1) 1 The Dear Bill Book is a compilation of letters which was given to Professor Hamilton upon his retirement in 1963; it will be referred to from here on as DBB. 2 55Table of Contents 1. Preface......................................................................................................................... 5 2. Introduction:................................................................................................................ 6 3. Childhood.................................................................................................................. 10 4. Cornell Student ......................................................................................................... 13 5. Starting a Family....................................................................................................... 17 6. Cornell Professor ..................................................................................................... -

(Evolution) Prior to Darwin's Origin of Species

Theories of Species Change (Evolution) Prior to Darwin’s Origin of Species Theories of Species Change Prior to Darwin Entangled with: 1. Theories of geological change. 2. Theories of heredity. 3. And theories of ontogenesis, that is, of individual development– embryology. Notions of Species in the Classical Period of Greece Plato: the essence or form of an organism is eternal and unchanging; embodiment only the appearance of that form. Aristotle: the essence or form of an organism is incorporated in the physical body; the only kind of eternity enjoyed is through continued reproduction. Theories of Species Change in the Early Modern Period Descartes: gradual evolution of physical system according to fix laws (Discourse on Method, 1628). Buffon (1707-88) and Linnaeus (1707-78): God created a limited number of species, but through hybridization and impact of environment, new species appear. Kant: evolutionary development from earth possible only if earth already construed as purposive; species change possible but no evidence (Critique of Judgment, 1790). Transformation of one species into another through change of scaling, from D’Arcy Thompson, On Growth and Form (1942). Carus’s illustration of the Richard Owen’s illustration of the archetype archetype, from his On the Nature of Limbs (1849) Georges Cuvier (1769-1832). Portrait by François-André Vincent Adam’s Mammoth, found in Siberia in 18th century; St. Petersburg Natural History Museum Cuvier’s illustration of the Siberian mammoth; he identified it as an extinct species of elephant (1796). Cuvier’s illustration of the “Ohio Animal,” which he named “mastodon.” Megatherium (i.e., “large animal”), discovered in South America, described by Cuvier as an extinct creature similar to the modern sloth.