Considering Lead Poisoning As a Criminal Defense Deborah W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republican Appointees and Judicial Discretion: Cases Studies from the Federal Sentencing Guidelines Era

Republican Appointees and Judicial Discretion: Cases Studies From the Federal Sentencing Guidelines Era Professor David M. Zlotnicka Senior Justice Fellow – Open Society Institute Nothing sits more uncomfortably with judges than the sense that they have all the responsibility for sentencing but little of the power to administer it justly.1 Outline of the Report This Report explores Republican-appointed district court judge dissatisfaction with the sentencing regime in place during the Sentencing Guideline era.2 The body of the Report discusses my findings. Appendix A presents forty case studies which are the product of my research.3 Each case study profiles a Republican appointee and one or two sentencings by that judge that illustrates the concerns of this cohort of judges. The body of the Report is broken down as follows: Part I addresses four foundational issues that explain the purposes and relevance of the project. Parts II and III summarizes the broad arc of judicial reaction to aThe author is currently the Distinguished Service Professor of Law, Roger Williams University School of Law, J.D., Harvard Law School. During 2002-2004, I was a Soros Senior Justice Fellow and spent a year as a Visiting Scholar at the George Washington University Law Center and then as a Visiting Professor at the Washington College of Law. I wish to thank OSI and these law schools for the support and freedom to research and write. Much appreciation is also due to Dan Freed, Ian Weinstein, Paul Hofer, Colleen Murphy, Jared Goldstein, Emily Sack, and Michael Yelnosky for their helpful c omments on earlier drafts of this Report and the profiles. -

The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History The Advocate Student Publications 3-27-1995 The Advocate The Advocate, Fordham Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/student_the_advocate Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation The Advocate, Fordham Law School, "The Advocate" (1995). The Advocate. Book 117. http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/student_the_advocate/117 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Advocate by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ADVOCATE Fordham Law School',? Student Newspaper since 1967 Vol. XXVII, No.9 Fordham University School of Law • © 1995 The Advocate March 27, 1995 Auction Breaks the Bank .-------------------......;---__. Annual Public Service New Yorker. The auction's Event Reaps Record proceeds help finance pub Batts On Hotnophobia, S90,OOO! lic interest work by the law students. by David Bowen and Earl A. Wilson First Years, and O.}. More than one auction Fordham's Fourth An rhere are, in effect two By Jeffrey Jackson auctions: a silent and a live I was running a little late on nual StudentSp onsored Fel my way to the interview withJ udge lowship Goods and Services auction. The Silent Auction, Batts. Radcliffe College. Harvard Auction raised more than which began at about 7:00 Law School. Clerk for Judge Pierce. Associate at Cravath, Swain and $90,000 on Tuesday March 7 PM in theAtriUm,had tables Moore. -

President Donald Trump's War on Federal Judicial Diversity

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2019 President Donald Trump's War on Federal Judicial Diversity Carl Tobias University of Richmond - School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Courts Commons Recommended Citation Carl Tobias, President Donald Trump's War on Federal Judicial Diversity, 54 Wake Forest L. Rev. 531 (2019). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP'S WAR ON FEDERAL JUDICIAL DIVERSITY Carl Tobias• In Donald Trump's 2016 presidential campaign, the candidate promised to nominate and confirm federal judges who would possess ideologically conservative perspectives. Across President Trump's first twenty-seven months, the chief executive implemented numerous actions to effectuate his campaign pledge. Indeed, federal judicial selection may be the area in which President Trump has achieved the most substantial success throughout his first twenty-seven months in office, as many of Trump's supporters within and outside the government recognize. Nevertheless, the chief executive's achievements, principally when nominating and confirming stalwart conservatives to the appellate court bench, have imposed numerous critical detrimental effects. Most important for the purposes of this Article, a disturbing pattern that implicates a stunning paucity of minority nominees materialized rather quickly. Moreover, in the apparent rush to install staunch conservative ideologues in the maximum possible number of appeals court vacancies, the Republican White House and Senate majority have eviscerated numerous invaluable, longstanding federal judicial selection conventions. -

SUPREME COURT of the UNITED STATES ALED OCTOBER TERM, 2018 DEC 12 2018 DEAN LOREN, Petitioner, OFFICE of the CLERK SUPREME COURT U C

&Iflui-- No. 18-5925 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES ALED OCTOBER TERM, 2018 DEC 12 2018 DEAN LOREN, Petitioner, OFFICE OF THE CLERK SUPREME COURT U C, V. CITY OF NEW YORK, NEW YORK, et al. ON PETITION OFR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT PETITION FOR REHEARING TO JOIN 18-5925 ARGUMENT WITH 17-1702: (1) JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR FAILURE TO RECUSE re: PRIOR RECUSAL BLAKELY V. WELL, 05-cv- 4846, RECORDED ON TAPE CALLING LOREN "A MISERABLE FAG" FROM 2 CIR BENCH; (2) JUSTICE BADER GINSBURG FAILURE TO RECUSE re: BLACKLISTING ATTORNEY DORIS SASSOWER AND DEAN LOREN FOR EXPOSING MADOFF; BOTH RECUSALS (1) & (2) SUBSTANTIALLY RELATED TO CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS' RECUSAL, WHO , RECUSED HIMSELF IN THIS PETITION FOR PERSONAL INVOLVEMENT IN LOREN V. LEVY, US SUPREME CT CASE 05-6091, 2ND CIR 05-cv- 4846, MADOFF RENTED COURTS AND JUDICIARY EMPLOYEE KYLE WOOD. DEAN LOREN, ESQ. Petitioner Pro Se, IFP 203 West 107th Street, Apt. 98A New York, New York 10025 dean!orengmai1.com C (718)277-1367 December 12, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES..........................................................................................................ii PETITION FOR REHEARING ......................................................................................................1 REASONS FOR GRANTING THE PETITION.............................................................................1 1. Should Justice Sotomayor's Failure To Recuse re: Prior Recusal - September 11, 2006 taped bench remarks 2' Cir 05-cv-4846 calling Loren a "Miserable Fag"; Father O'Hare relationship; and failing to note Loren recusal on her US Supreme Court Application - constitute substantial prejudice to Loren's 18-5925 argument with 17-1702, that substantially involves Chief Justice Roberts and his recusal? .............................3 H. -

Considering Lead Poisoning As a Criminal Defense

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 20 Number 3 Article 1 1993 Considering Lead Poisoning as a Criminal Defense Deborah W. Denno Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Deborah W. Denno, Considering Lead Poisoning as a Criminal Defense, 20 Fordham Urb. L.J. 377 (1993). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol20/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSIDERING LEAD POISONING AS A CRIMINAL DEFENSE Deborah W. Denno* I. Introduction No doubt, Frank XI stood apart from his peers. At age twenty- three, he already had an extensive criminal record: twenty-seven offi- cially recorded offenses asa juvenile and ten offenses as an adult. His first recorded offense was for truancy at age ten. From ages twelve to twenty-two, he had at least two and as many as six recorded offenses every year. These offenses included robbery, assault, theft, and re- peated disorderly conduct. Frank was a subject in the "Biosocial Study," one of this country's largest "longitudinal" studies of biological, sociological, and environ- mental predictors of crime.2 A longitudinal study analyzes the same group of individuals over a period of time.' The Biosocial Study is unique because it analyzed numerous variables relating to a group of nearly one thousand males and females during the first twenty-four years of their lives: from the time the subjects' mothers were admitted into the same Philadelphia hospital to give birth until the subjects' twenty-fourth birthday. -

Case 1:14-Md-02542-VSB-SLC Document 1323 Filed 05/07/21 Page 1 of 35

Case 1:14-md-02542-VSB-SLC Document 1323 Filed 05/07/21 Page 1 of 35 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK x : IN RE: KEURIG GREEN MOUNTAIN SINGLE-SERVE No. 1:14-md-02542 (VSB) COFFEE ANTITRUST LITIGATION : No. 1:14-cv-04391 (VSB) : This Relates to the Indirect-Purchaser Actions x DECLARATION OF ROBERT N. KAPLAN IN SUPPORT OF INDIRECT PURCHASER PLAINTIFFS’ (1) MOTION FOR FINAL APPROVAL OF CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT AND APPROVAL OF PLAN OF ALLOCATION AND (2) MOTION FOR AN AWARD OF ATTORNEYS’ FEES, FOR REIMBURSEMENT OF EXPENSES, AND INCENTIVE AWARDS FOR THE NAMED PLAINTIFFS Case 1:14-md-02542-VSB-SLC Document 1323 Filed 05/07/21 Page 2 of 35 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page(s) TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ........................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 II. PROCEEDURAL HISTORY ................................................................................................. 4 A. Settlement Class Counsel’s Pre-Filing Investigation and Initial Proceedings Before this Court ............................................................................. 4 B. The Consolidated Amended Complaints and Defendant’s Motions to Dismiss ................................................................................................................... 5 C. Discovery ............................................................................................................... -

Nikolay Alexeyev RUSSIAN B

NIKOLAY ALEXEYEV RUSSIAN b. December 23, 1977 ACTIVIST “Without an ideal, nothing is possible.” Nikolay Alexeyev is Russia’s best-known and most quoted LGBT activist and the His leadership founder of Moscow Pride. In 2010 he won the first case on LGBT rights violations in Russia at the European Court of Human Rights. brought international Alexeyev was born and raised in Moscow. He graduated with honors from attention to LGBT Lomonosov Moscow State University, where he pursued postgraduate studies in rights in Russia. constitutional law. In 2001 the university forced him out, refusing to except his thesis on the legal restrictions of LGBT Russians. Claiming discrimination, he filed an appeal, but the Moscow district court denied it. In 2005, after publishing multiple books and legal reports on LGBT discrimination, Alexeyev fully dedicated himself to LGBT activism. He realized “that it wouldn’t be possible to change things in Russia just by writing” and that he should be involved in more direct activism. Despite an official ban on LGBT events, Alexeyev founded and served as the chief organizer of Gay Pride in Moscow. Participants in the Gay Pride parades were attacked and bullied by anti-gay protesters. Police arrested Alexeyev and fellow activists multiple times. Through both illegal public protests and legal appeals, Alexeyev’s uncompromising fight for the right to hold Moscow Pride drew international attention to the issue of LGBT rights in his country. In 2009, alongside Russian, French and Belarusian LGBT activists, Alexeyev organized a protest to denounce the inaction of the European Court in considering the legality of the Moscow Pride bans. -

Speaker Biographies

BRIEF BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES OF TODAY’S PROGRAM PRESENTERS FEATURED SPEAKER Kevin Richardson April 19, 1989 started off as a normal day for 14 year-old Kevin D. Richardson, but that night would change the course of his life and American society forever. After the brutal attack and sexual assault of jogger Trisha Ellen Meili in Central Park, the New York Police Department rounded up and arrested a total of 10 suspects, including Richardson. Despite there being no DNA and little evidence connecting himself and the four other teens to the crime, Richardson was charged and sentenced to serve 5 to 10 years in jail. After serving seven years for a crime he did not commit, Richardson was put on probation and released from prison. However, years later the conviction for the attack remained on his record. In 2002, New York District Attorney Robert Richardson joined forces with the other men falsely convicted and filed a lawsuit for $41 million, which was finally settled in 2014. In 2019, Netflix released When They See Us, a mini- series portraying the famous events of the case. The celebrated and award- winning show has brought the injustices Kevin Richardson along with Antron McCray, Raymond Santana, Korey Wise, and Yusef Salaam experienced back into the public’s attention. 30 years later, Kevin Richardson is an advocate for criminal justice reform and uses his personal experience with false coercions and unjust convictions to bring about change. He has partnered with the Innocence Project, a non- profit organization dedicated to exonerating wrongfully convicted people through DNA testing. -

Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law Yeshiva University

37-1 List of Faculty 11/19/2015 10:17 PM Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law Yeshiva University ADMINISTRATION Richard M. Joel, J.D., President, Yeshiva University. Melanie Leslie, J.D., Dean, Professor of Law. Richard A. Bierschbach, J.D., Vice Dean, Professor of Law. Matthew Levine, M.B.A., Associate Dean for Finance and Administration. David G. Martinidez, M.A., Associate Dean for Admissions. Judy Mender, J.D., Associate Dean for Students. Patricia J. Morrissy, B.A., Associate Dean for Career Advancement & Professionalism. Carissa Vogel, M.L.I.S., J.D., Associate Dean for Library Services, Director of the Law Library, Professor of Legal Research. Patricia Weiss, M.A., Associate Dean for Institutional Advancement. John DeNatale, B.A., Assistant Dean of Communications and Public Affairs. Valbona Myteberi, LL.B., LL.M., Assistant Dean of Graduate and International Programs. Jeanne Estilo Widerka, J.D., Assistant Dean for Admissions. David Udell, J.D., Executive Director of the National Center for Access to Justice, Visiting Professor from Practice. Christine Arlene N. Arrozal, B.S., M.A., Director of the Dean’s Office, Associate Director of Academic Affairs. Julie Anna Alvarez, J.D., Director of Alumni Career Services. Hasani Anthony, M.B.A., Director of Faculty Services. Kirsty Dymond, J.D., Director of Special Events. Joshua Epstein, J.D., Director of Graduate and International Programs. Jillian Gautier, J.D., Director of the Samuel and Ronnie Heyman Center for Corporate Governance. Jon D. Goldberg, M.A., Director of Student Finance. Sharon Lewis, J.D., Director of Alumni Affairs. Leslie S. Newman, J.D., Director of Lawyering and Legal Writing, Professor of Law. -

Office of the District Court Executive February 5, 2020 To

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T S O U T H E R N DISTRICT OF NEW YORK Office of the District Court Executive COLLEEN MCMAHON EDWARD A. FRIEDLAND Chief Judge District Court Executive February 5, 2020 To: Members of the Bar It is with a heavy heart, that the Southern District of New York advises you of, the passing of Senior Federal District Judge Deborah A. Batts on February 3, 2020. Judge Batts was the first openly gay Article III Judge. Judge Batts was appointed to the SDNY by President Clinton in 1994. She received her undergraduate degree from Radcliffe College in 1969 and she graduated from Harvard Law School in 1972. Following law school, she clerked for SDNY District Court Judge Lawrence W. Pierce. In 1973, Judge Batts became an associate at Cravath, Swaine & Moore. In 1979, she became an Assistant United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York in the Criminal Division. And, in 1984, Judge Batts joined the faculty at Fordham University School of Law and became an Associate Professor of Law in May, 1990. Judge Batts was a member of the CUNY School of Law Board of Visitors and the Board of Managers of the Havens Relief Fund Society. In June 2001, Judge Batts was appointed Team Member of the Crowley Program on International Human Rights’ Mission to Ghana to assess women’s rights in inheritance. In October, 2001, an oil portrait of Judge Batts by Simmie Knox, commissioned by the HSLA Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual Alumni/ae Committee, was unveiled at and presented to Harvard Law School. -

Deborah Batts, Federal Judge Set to Oversee Avenatti's Stormy Daniels

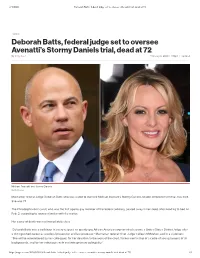

2/4/2020 Deborah Batts, federal judge set to oversee Avenatti trial, dead at 72 METRO Deborah Batts, federal judge set to oversee Avenatti’s Stormy Daniels trial, dead at 72 By Emily Saul February 3, 2020 | 1:13pm | Updated Michael Avenatti and Stormy Daniels Getty Images Manhattan federal Judge Deborah Batts who was slated to oversee Michael Avenatti’s Stormy Daniels-related embezzlement trial, has died. She was 72. The Philadelphia-born jurist, who was the ¼rst openly gay member of the federal judiciary, passed away in her sleep after heading to bed on Feb. 2, according to sources familiar with the matter. Her cause of death was not immediately clear. “Deborah Batts was a trailblazer in every respect: an openly gay African-American woman who became a United States District Judge after a distinguished career as a federal prosecutor and law professor,” Manhattan federal Chief Judge Colleen McMahon said in a statement. “She will be remembered by her colleagues for her devotion to the work of the court, for her mentorship of a cadre of young lawyers of all backgrounds, and for her infectious smile and extraordinary collegiality.” https://nypost.com/2020/02/03/deborah-batts-federal-judge-set-to-oversee-avenattis-stormy-daniels-trial-dead-at-72/ 1/2 2/4/2020 Deborah Batts, federal judge set to oversee Avenatti trial, dead at 72 “Our hearts are broken at her premature passing,” said McMahon. The Clinton appointee was set to preside over the upcoming trial of embattled attorney Avenatti on embezzlement charges, for allegedly pocketing money meant for his well-known client Daniels, also known as Stephanie Cliºord. -

100 Years of Women at Fordham Law: a Foreword and Reflection

100 YEARS OF WOMEN AT FORDHAM: A FOREWORD AND REFLECTION Elizabeth B. Cooper* As we reflect back on 100 Years of Women at Fordham Law School, we have much to celebrate. In contrast to the eight women who joined 312 men at the Law School in 1918—or 2.6 percent of the class—women have constituted approximately 50 percent of our matriculants for decades.1 Life for women at the Law School has come a long way in more than just numbers. For example, in 1932, the Law School recorded the first known practice of “Ladies’ Day,” a day on which some professors would call on women, who otherwise were expected to be silent in their classes.2 In this context, one can only imagine the experience of Mildred Fischer, the first woman to serve as Editor-in-Chief of the Fordham Law Review, in 1936.3 We have come a long way and, thankfully, it is no longer unusual to see a woman voted Editor-in-Chief of the Law Review and our other scholarly journals. Women also have rightly claimed their place at the head of the Student Bar Association and countless student organizations. From the very start, however, women have succeeded as scholars and advocates at the Law School and in their careers. Fordham Law alumnae have a strong tradition of public service. Early on, Ruth Whitehead Whaley, the first African American woman to graduate from the Law School (1924), finished her studies with cum laude honors at the age * Associate Professor of Law, Fordham University School of Law; Faculty Director, Feerick Center for Social Justice and Faculty Co-Director of the Stein Scholars program.