The Geological Heritage of Clare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mountmellick, Mountrath, Abbeyleix, Co. Laois, Monasterevin, Co

3. Group 2: Mountmellick, Mountrath, Abbeyleix, Co. Laois, and Monasterevin, Co. Kildare. 3.1. Mountmellick, Co. Laois 3.1.1. Summary Details: Mountmellick is located 11km from the regional hub town of Portlaoise. The population of Mountmellick is currently 2,872 as per the results of the 2006 Census. This is projected to increase to 4,540 by 2018 (see Appendix B). It is forecast that up to 500 houses will be connected in Mountmellick over the next ten years. The projected figure is based on housing completion figures, census population report, Laois housing strategy and Laois County Development Plan. The main employer in the town is St. Vincent’s Hospital. Another significant I/C load in the town is Standex Ireland Ltd. It is expected that with population growth at least a proportional increase in I/C customers will develop. Mountmellick is situated 7km from the existing Portarlington feeder main. 3.1.2. Summary Load Analysis: Mountmellick, Co. Laois. Source: Networks cost estimates report June 2007 Industrial/Commercial Load Summary Forecast: Total EAC 2014 6,639 MWh 226,600 Therms Peak Day 2014 37,958 kWh 1,295 Therms New Housing Summary Forecast: New Housing Load (Therm) 260,000 (year 10) New Housing Load (MWh) 7,620 (year 10) 3.1.3. Solutions: The most economic option for supplying Mountmellick town is by installing a 250mm PE100 SDR17 feeder main from Portlaoise (6.8 km approx). A reinforcement of the Portlaoise network is also required as a result of the connection of Mountmellick to this network, the costs of which have been included in the analysis. -

Wales-Ireland Travelogue 2009

WALES AND IRELAND TRIP MAY 12 TO JUNE 4, 2009 What a coincidence! Meaningless, to be sure - but a coincidence, nonetheless. Our trip to the British Isles in 2009 began and ended one day earlier than our trip to Scotland, May 14 to June 5, 2001. (One can only hope that September of this year doesn't hold the same sort of unpleasant surprise that was visited upon us eight years ago.) OK, so I made a "small" error - we are departing two days earlier, not one. And, OK, so it wasn't much of a coincidence, was it? I mean, a real coincidence - one of excruciating consequence - occurred at the Polo Grounds in NYC on October 3, 1951 when Ralph Branca of the Blessed Brooklyn Dodgers was called in to pitch in the 9th inning and, by coincidence, Bobby Thomson of the Bestial New York Giants happened to come to bat, and, by coincidence, Mr. Branca happened to throw a pitch that the aforementioned Mr. Thomson happened to swing at, and, by coincidence, made contact with said pitch and drove it a miserable 309 feet into the first row of the left- field seats of the absurdly apportioned Polo Grounds, thus ending the Dodgers' season and causing a certain 12-year-old, watching on TV, in Brooklyn to burst into tears. Now that was a coincidence! But I digress. Tuesday, May 12 to Wednesday, May 13 Rather than leaving our car at the Seattle Airport Parking Garage (cost for three-plus weeks $468) or at an airport hotel (about $335) we decide to try the new Gig Harbor Taxi (at $95 each way, including tip). -

Inistioge Local Area Plan

INISTIOGE LOCAL AREA PLAN KILKENNY COUNTY COUNCIL PLANNING DEPARTMENT 19th July 2004 Inistioge Local Area Plan 2004 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 LEGAL BASIS 1 1.2 PLANNING CONTEXT 1 1.3 LOCATIONAL CONTEXT 2 1.4 PREVIOUS PLANS / STUDIES 2 1.5 HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT 2 1.6 URBAN STRUCTURE 3 1.6.1 THE WATER FRONT 4 1.6.2 THE CENTRE 5 1.6.3 THE OTHER APPROACHES 5 1.7 POPULATION 6 1.8 PLANNING HISTORY 6 1.9 DESIGNATIONS 6 1.9.1 NATURAL HERITAGE AREAS AND SPECIAL AREA OF CONSERVATION 6 1.9.2 ARCHAEOLOGY 6 1.9.3 RECORD OF PROTECTED STRUCTURES 7 1.9.4 ECOLOGY 7 1.10 NATIONAL SPATIAL STRATEGY 7 1.11 PUBLIC CONSULTATION 8 2 POLICIES AND OBJECTIVES 10 2.1 COMMUNITY FACILITIES/AMENITY / RECREATION 10 2.2 EDUCATION 11 2.3 HOUSING AND POPULATION 11 2.4 STREET LIGHTING 12 2.5 STREET FURNITURE 13 2.6 EMPLOYMENT 13 2.7 BOUNDARY TREATMENT OF APPROACH ROADS INTO THE VILLAGE 13 2.8 MAINTENANCE OF BUILDINGS 14 2.9 TIDINESS 15 2.9.1 TIDY TOWNS 15 2.9.1.1 The River Bank 15 2.9.1.2 The Square 15 2.9.2 GRAVEYARDS 16 2.10 SERVICES 16 2.11 SEWAGE TREATMENT 17 2.12 SURFACE WATER DRAINAGE 17 2.13 WATER SUPPLY 18 2.14 CAR PARKING 18 2.15 TRANSPORTATION / ROADS / FOOTPATHS 19 2.16 ADVERTISING 21 2.17 HEALTHCARE 22 2.18 SIGNPOSTING 22 2.19 CONSERVATION 22 2.19.1 ARCHAEOLOGY 22 2.19.2 THE RECORD OF PROTECTED STRUCTURES 23 2.19.3 THE ARCHITECTURAL CONSERVATION AREA 23 2.20 TOURISM 26 2.20.1 WOODSTOCK 26 2.20.2 THE RIVER NORE 27 _ ____________________________________________________________________ i Inistioge Local Area Plan 2004 2.21 WASTE DISPOSAL 27 3 DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVES -

The Castlecomer Plateau

23 The Castlecomer plateau By T. P. Lyng, N.T. HE Castlecomer Plateau is the tableland that is the watershed between the rivers Nore and Barrow. Owing T to the erosion of carboniferous deposits by the Nore and Barrow the Castlecomer highland coincides with the Castle comer or Leinster Coalfield. Down through the ages this highland has been variously known as Gower Laighean (Gabhair Laighean), Slieve Margy (Sliabh mBairrche), Slieve Comer (Sliabh Crumair). Most of it was included within the ancient cantred of Odogh (Ui Duach) later called Ui Broanain. The Normans attempted to convert this cantred into a barony called Bargy from the old tribal name Ui Bairrche. It was, however, difficult territory and the Barony of Bargy never became a reality. The English labelled it the Barony of Odogh but this highland territory continued to be march lands. Such lands were officially termed “ Fasach ” at the close of the 15th century and so the greater part of the Castle comer Plateau became known as the Barony of Fassadinan i.e. Fasach Deighnin, which is translated the “ wi lderness of the river Dinan ” but which officially meant “ the march land of the Dinan.” This no-man’s land that surrounds and hedges in the basin of the Dinan has always been a boundary land. To-day it is the boundary land between counties Kil kenny, Carlow and Laois and between the dioceses of Ossory, Kildare and Leighlin. The Plateau is divided in half by the Dinan-Deen river which flows South-West from Wolfhill to Ardaloo. The rim of the Plateau is a chain of hills averag ing 1,000 ft. -

Prior-Wandesforde Papers (Additional)

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 173 Prior-Wandesforde Papers (Additional) (SEE ALSO COLLECTION LISTS No. 52 & 101) (MSS 48,342-48,354) A small collection of estate and colliery papers of the Prior-Wandesforde family of Castlecomer, Co. Kilkenny, 1804-1969. Compiled by Owen McGee, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction....................................................................................................................... 3 I. The Castlecomer Colliery ............................................................................................. 5 I.i. Title deeds to the mines (1819-1869)........................................................................ 5 I.ii. Business accounts for the Castlecomer mines (1818-1897)..................................... 8 I.iii. Castlecomer Collieries Ltd. (1903-1969).............................................................. 10 I.iii.1 Business correspondence (1900-1928)............................................................ 10 I.iii.2 General accounts (1920-1963) ........................................................................ 12 I.iii.3 Company stock and production accounts (1937-1966)................................... 14 I.iii.4 Staff-pay accounts (1940-1966)...................................................................... 15 I.iii.5 Accident insurance claims (1948-1967).......................................................... 16 I.iii.6 Employer and Trade Union related material (1949-1959)............................. -

Laois TASTE Producer Directory

MEET the MAKERS #WelcomeToTASTE #LaoisTASTE #WelcomeToTASTE #LaoisTASTE Aghaboe Farm Foods Product: Handmade baking Main Contact: Niamh Maher Tel: +353 (0)86 062 9088 Email: [email protected] Address: Keelough Glebe, Pike of Rushall, Portlaoise, Co. Laois, Ireland. Aghaboe Farm Foods was set up by Niamh Maher in 2015. From as far back as Niamh can remember, she has always loved baking tasty cakes and treats. Today, Aghaboe Farm Foods has grown into an award-winning artisan bakery. Specialising in traditional handmade baking, Niamh uses only natural ingredients. “Our flavours change with the seasons and where possible we use local ingredients to ensure the highest AWARDS quality and flavour possible”. Our selection includes cakes, GOLD MEDAL WINNER Blas na hÉireann 2019 tarts, muffins & brownies. Aghaboe Farm Foods sell directly BEST IN LAOIS through farmers’ markets and by private orders through Blas na hÉireann 2019 Facebook. “All of our bespoke products are made to order to BEST IN FARMERS’ MARKET suit customer’s needs”. Blas na hÉireann 2019 In 2017 Aghaboe Farm Foods won Silver at Blas na hÉireann, and in 2018 they achieved a Great Taste Award. In 2019 Niamh has once again been successful, winning a Blas na hÉireann award for her Christmas cake. @aghaboefarmfoods @aghaboefarmfoods #WelcomeToTASTE #LaoisTASTE An Sean-Teach www.anseanteach.com Product: Botanical Gins & Cream Liqueurs Main Contact: Brian Brennan / Carla Taylor Tel: +353 (0)87 261 9151 / +353 (0)86 309 5235 Email: [email protected] Address: Aughnacross, Ballinakill, Co. Laois, Ireland. An Sean-Teach, meaning The Old House in Irish, is named after the traditional thatched house on the farm where the business is located in Co. -

Laois-Kilkenny Reinforcement Project

Laois-Kilkenny Reinforcement Project Application for Planning Approval Planning Report ESBI Engineering Solutions Stephen Court, 18/21 St Stephen‟s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland Telephone+353-1-703 8000 Fax+353-1-661 6600 www.esbi.ie January 2013 File Reference: PE687-F261 Client / Recipient: EirGrid Project Title: Laois-Kilkenny Reinforcement Project Report Title: Planning Application Report Report No.: PE687-F261-R261-022-003 Rev. No.: 003 Volume 1 of 1 Prepared by: Brendan Allen Title: Senior Planner Spatial Planning Unit APPROVED: B.Dee DATE: January 2013 TITLE: Team Leader Spatial Planning Unit Latest Revision Summary: COPYRIGHT © ESB INTERNATIONAL LIMITED ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, NO PART OF THIS WORK MAY BE MODIFIED OR REPRODUCED OR COPIES IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS - GRAPHIC, ELECTRONIC OR MECHANICAL, INCLUDING PHOTOCOPYING, RECORDING, TAPING OR INFORMATION AND RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, OR USED FOR ANY PURPOSE OTHER THAN ITS DESIGNATED PURPOSE, WITHOUT THE WRITTEN PERMISSION OF ESB INTERNATIONAL LIMITED. Laois-Kilkenny Reinforcement Project Planning Report Table of Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Report Context 1 1.2 Details of the Applicant 1 1.3 Project Overview 1 1.4 Purpose and Structure of this Planning Report 4 2 Project Need and Alternatives Considered 5 2.1 Project Justification 5 2.2 Existing Electricity Transmission Infrastructure 5 2.3 Limitations of the Existing Electricity Infrastructure 9 2.4 Reinforcement Options Considered 10 2.5 Preferred Reinforcement Option 13 3 Project Development 15 3.1 EirGrid‟s Project Development and Consultation -

Ireland P a R T O N E

DRAFT M a r c h 2 0 1 4 REMARKABLE P L A C E S I N IRELAND P A R T O N E Must-see sites you may recognize... paired with lesser-known destinations you will want to visit by COREY TARATUTA host of the Irish Fireside Podcast Thanks for downloading! I hope you enjoy PART ONE of this digital journey around Ireland. Each page begins with one of the Emerald Isle’s most popular destinations which is then followed by several of my favorite, often-missed sites around the country. May it inspire your travels. Links to additional information are scattered throughout this book, look for BOLD text. www.IrishFireside.com Find out more about the © copyright Corey Taratuta 2014 photographers featured in this book on the photo credit page. You are welcome to share and give away this e-book. However, it may not be altered in any way. A very special thanks to all the friends, photographers, and members of the Irish Fireside community who helped make this e-book possible. All the information in this book is based on my personal experience or recommendations from people I trust. Through the years, some destinations in this book may have provided media discounts; however, this was not a factor in selecting content. Every effort has been made to provide accurate information; if you find details in need of updating, please email [email protected]. Places featured in PART ONE MAMORE GAP DUNLUCE GIANTS CAUSEWAY CASTLE INISHOWEN PENINSULA THE HOLESTONE DOWNPATRICK HEAD PARKES CASTLE CÉIDE FIELDS KILNASAGGART INSCRIBED STONE ACHILL ISLAND RATHCROGHAN SEVEN -

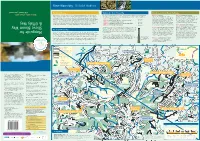

Mapguide for Slieve Bloom Way & Offaly

Slieve Bloom Way Slí Sliabh Bladhma Siúl tamall, fan tamall fan tamall, Siúl Walk a while, stay a while a stay while, a Walk The Slieve Blooms Walking the Slieve Bloom Way Directions to Slieve Bloom Trailheads Situated close to the geographical centre of Ireland, the Slieve Bloom Region is made up of forests, The Slieve Bloom Way is best accessed at one of six key trailheads which provide car parking and are Trailhead 1 Glenbarrow Trailhead 4 Kinnitty Forest Entrance blanket bog of a type which is unique to Ireland, interspersed with hidden valleys of great character, reasonably close to services such as shops, restaurants and accommodation. They are located at; Start from Rosenallis village on the R422 Kinnitty village is located on the R421 between and interest to lovers of archaeology and nature. It is an extremely peaceful area which permits the between the towns of Mountmellick and Birr. At the towns of Mountmellick and Birr. Take the opportunity to be close to nature. The wild and mysterious Slieve Bloom Mountains form a link between Trailhead 1 - Glenbarrow Carpark N 367 081 the sharp bend opposite the Church take the R421 following the signposts for Cadamstown but the counties of Laois and Offaly and boast hidden valleys and rocks ranging in age from 300 to 450 Trailhead 2 - Brittas Woods Entrance at Clonaslee Village N 317 106 minor road signposted Glenbarrow. After 2.5Km after only 200m veer right onto the R440 & Offaly Way Offaly & turn right at a 3-way junction, and after a signposted Mountrath. [The trailhead is million years. -

En — 24.03.1999 — 003.001 — 1

1985L0350 — EN — 24.03.1999 — 003.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 27 June 1985 concerning the Community list of less-favoured farming areas within the meaning of Directive 75/ 268/EEC (Ireland) (85/350/EEC) (OJ L 187, 19.7.1985, p. 1) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Council Directive 91/466/EEC of 22 July 1991 L 251 10 7.9.1991 ►M2 Council Directive 96/52/EC of 23 July 1996 L 194 5 6.8.1996 ►M3 Commission Decision 1999/251/EC of 23 March 1999 L 96 29 10.4.1999 Corrected by: ►C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 266, 9.10.1985, p. 18 (85/350/EEC) ►C2 Corrigendum, OJ L 281, 23.10.1985, p. 17 (85/350/EEC) ►C3 Corrigendum, OJ L 74, 19.3.1986, p. 36 (85/350/EEC) 1985L0350 — EN — 24.03.1999 — 003.001 — 2 ▼B COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 27 June 1985 concerning the Community list of less-favoured farming areas within the meaning of Directive 75/268/EEC (Ireland) (85/350/EEC) THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Having regard to Council Directive 75/268/EEC of 28 April 1975 on mountain and hill farming and farming in certain less-favoured areas( 1), aslastamended by Directive 82/786/EEC ( 2), and in particular Article 2 (2) thereof, Having regard to the proposal from the Commission, Having regard to the opinion of the European Parliament (3), WhereasCouncil Directive 75/272/EEC of 28 April 1975 concerning the Community list of less-favoured farming areas within -

Midlands-Our-Past-Our-Pleasure.Pdf

Guide The MidlandsIreland.ie brand promotes awareness of the Midland Region across four pillars of Living, Learning, Tourism and Enterprise. MidlandsIreland.ie Gateway to Tourism has produced this digital guide to the Midland Region, as part of suite of initiatives in line with the adopted Brand Management Strategy 2011- 2016. The guide has been produced in collaboration with public and private service providers based in the region. MidlandsIreland.ie would like to acknowledge and thank those that helped with research, experiences and images. The guide contains 11 sections which cover, Angling, Festivals, Golf, Walking, Creative Community, Our Past – Our Pleasure, Active Midlands, Towns and Villages, Driving Tours, Eating Out and Accommodation. The guide showcases the wonderful natural assets of the Midlands, celebrates our culture and heritage and invites you to discover our beautiful region. All sections are available for download on the MidlandsIreland.ie Content: Images and text have been provided courtesy of Áras an Mhuilinn, Athlone Art & Heritage Limited, Athlone, Institute of Technology, Ballyfin Demense, Belvedere House, Gardens & Park, Bord na Mona, CORE, Failte Ireland, Lakelands & Inland Waterways, Laois Local Authorities, Laois Sports Partnership, Laois Tourism, Longford Local Authorities, Longford Tourism, Mullingar Arts Centre, Offaly Local Authorities, Westmeath Local Authorities, Inland Fisheries Ireland, Kilbeggan Distillery, Kilbeggan Racecourse, Office of Public Works, Swan Creations, The Gardens at Ballintubbert, The Heritage at Killenard, Waterways Ireland and the Wineport Lodge. Individual contributions include the work of James Fraher, Kevin Byrne, Andy Mason, Kevin Monaghan, John McCauley and Tommy Reynolds. Disclaimer: While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy in the information supplied no responsibility can be accepted for any error, omission or misinterpretation of this information. -

Balkatach Hypothesis: a New Model for the Evolution of the Pacific, Tethyan, and Paleo-Asian Oceanic Domains

Research Paper GEOSPHERE Balkatach hypothesis: A new model for the evolution of the Pacific, Tethyan, and Paleo-Asian oceanic domains 1,2 2 GEOSPHERE, v. 13, no. 5 Andrew V. Zuza and An Yin 1Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada 89557, USA 2Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095-1567, USA doi:10.1130/GES01463.1 18 figures; 2 tables; 1 supplemental file ABSTRACT suturing. (5) The closure of the Paleo-Asian Ocean in the early Permian was accompanied by a widespread magmatic flare up, which may have been CORRESPONDENCE: avz5818@gmail .com; The Phanerozoic history of the Paleo-Asian, Tethyan, and Pacific oceanic related to the avalanche of the subducted oceanic slabs of the Paleo-Asian azuza@unr .edu domains is important for unraveling the tectonic evolution of the Eurasian Ocean across the 660 km phase boundary in the mantle. (6) The closure of the and Laurentian continents. The validity of existing models that account for Paleo-Tethys against the southern margin of Balkatach proceeded diachro- CITATION: Zuza, A.V., and Yin, A., 2017, Balkatach hypothesis: A new model for the evolution of the the development and closure of the Paleo-Asian and Tethyan Oceans criti- nously, from west to east, in the Triassic–Jurassic. Pacific, Tethyan, and Paleo-Asian oceanic domains: cally depends on the assumed initial configuration and relative positions of Geosphere, v. 13, no. 5, p. 1664–1712, doi:10.1130 the Precambrian cratons that separate the two oceanic domains, including /GES01463.1. the North China, Tarim, Karakum, Turan, and southern Baltica cratons.