Towards a Deeper Understanding of the Indigenous Experience Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report Still from Infinitude by Scott Portingale, Photo Supplied

2015 annual report Still from Infinitude by Scott Portingale, photo supplied Alberta Cantonese Opera Festival presents War Drum in Golden Mountain, photo supplied “CONFUSEMENT” by Nina Haggerty artist Scott Berry, Michalene Giesbrecht, Sandra Olarte, and Stephanie Gruson in photo by Jenna Turner Firefly Theatre & Circus’ “The Playground”, photo by Studio E Photography 2015 annual report The Edmonton Arts Council The Edmonton Arts Council is a not-for-profit society and charitable organization that supports and promotes the arts community in Edmonton. The EAC works to increase the profile and involvement of arts and culture in all aspects of our community life through activities that: Invest Represent Build Create in Edmonton Edmonton’s arts partnerships and awareness of festivals, arts community to initiate projects the quality, organizations government and that strengthen variety, and and individual other agencies our community. value of artistic artists through and provide work produced municipal, expert advice on in Edmonton. corporate, and issues that affect private funding. the arts. 1 "Navigating Boundaries” by Kelsey Stephenson and Jes McCoy Reconciliation in Solidarity Edmonton (RISE) Community Heart Garden at Harcourt House, photo by Kelsey Stephenson installed at City Hall, photo by Gibby Davis Angela Gladue, Lana Whiskeyjack and Logan Alexis 2 Drummers at Channeling Connections, photo by Brad Crowfoot Katherine Kerr and Edmonton Community Foundation’s Alex Draper, Annette Aslund and Jenna Turner, photo by Brad Crowfoot photo -

SKIPP Virtual Colloquium Event Transcript Friday June 12, 2020 - Connecting with Indigenous-Engaged Research, Research Creation, and Scholarship in the Fine Arts

SKIPP Virtual Colloquium Event Transcript Friday June 12, 2020 - Connecting with Indigenous-engaged Research, Research Creation, and Scholarship in the Fine Arts Thomas Barker: Hello everyone, welcome to the Virtual Colloquium on Indigenous-engaged Research, my name is Tom Barker and I'm a professor in the Communication and Technology Master's Program. I will be your host today. Just as a reminder, we will be recording those presenters today who have given us their permission to do so. For our participants, please keep your video off and your microphones muted, we have a lot of participants we find that that practice works best for us. If you have any trouble viewing any of the PowerPoint presentations today, simply click the “view options” at the top of your screen and select “fit to screen,” that will ensure that your presentation is properly sized for your screen. Our technical moderator today is Rebecca Gray, so if you have any technical questions, please send her a message in the chat. You can click on Rebecca's name in the chat window and privately to her. Our format today is to invite our speakers to share their stories and then we will open it up for discussion. So if you don't mind, hold all your questions until the presentations are complete. Before we move on to our first presenter I would like to remind you that this colloquium is coming from the University of Alberta in Edmonton, we are located on Treaty 6 territory, traditional homelands of the Métis and Papaschase Cree people. -

Abuse of Power in Relationships and Sexual Health

Child Abuse & Neglect 58 (2016) 12–23 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Child Abuse & Neglect Research article Abuse of power in relationships and sexual health a,∗ b b,1 c Dionne Gesink , Lana Whiskeyjack , Terri Suntjens , Alanna Mihic , d,2 Priscilla McGilvery a Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, 155 College St., 6th Floor, Toronto, Ontario M5T 3M7, Canada b Blue Quills First Nations College, Box 279, St. Paul, Alberta T0A 3A0, Canada c University of Toronto, 155 College St., Toronto, Ontario M5T 3M7, Canada d Saddle Lake Health Center, P.O. Box 160, Saddle Lake, Alberta T0A 3T0, Canada a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: STI rates are high for First Nations in Canada and the United States. Our objective was to Received 23 January 2016 understand the context, issues, and beliefs around high STI rates from a nêhiyaw (Cree) Received in revised form 31 May 2016 perspective. Twenty-two in-depth interviews were conducted with 25 community partici- Accepted 2 June 2016 pants between March 1, 2011 and May 15, 2011. Interviews were conducted by community researchers and grounded in the Cree values of relationship, sharing, personal agency and Keywords: relational accountability. A diverse purposive snowball sample of community members Abuse of power were asked why they thought STI rates were high for the community. The remainder of Sexually transmitted infections the interview was unstructured, and supported by the interviewer through probes and Sexual abuse sharing in a conversational style. -

Management Report

MANAGEMENT REPORT Date: March 19, 2021 Authors: Megan Langley, Manager, Neighbourhood Services VanDocs#: DOC/2021/071555 Meeting Date: March 24, 2021 TO: Library Board FROM: Julie Iannacone, Director, Neighbourhood & Youth Services 2019-2020 Actions to address the Truth and Reconciliation SUBJECT: Commission Recommendations SUMMARY This report provides a summary of VPL’s 2019-2020 activities to address the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Calls to Action. In the VPL 2017-2019 Strategic Plan, this work was aligned with operating plan initiative 5.4, Address the TRC Calls to Action within VPL, and it continues in the VPL 2020-2023 Strategic Plan which prioritizes Truth and Reconciliation throughout. PURPOSE This report is for information. RECOMMENDATION That the Board receive this report for information. COMMITTEE DISCUSSION Trustees commented on the value of the report for sharing VPL’s work on Reconciliation and thanked staff for the work and report. Trustee Pruden noted opportunities to provide a definition for decolonization, include references to the TRC Calls to Action, and to share VPL’s work related to governance, including adding Indigenous consideration to policies and having two Indigenous people in leadership roles as trustees. These have been incorporated below. Trustees asked DOC/2021/071555 Page 1 of 10 about challenges in the work and ways of measuring. Trustee Jules noted the importance of establishing ongoing funding for this work in order to effectively address structural biases. POLICY VPL’s 2020-2023 Strategic Plan prioritizes Truth and Reconciliation. During the strategic plan engagement, conversations with the public and key stakeholders highlighted the need to bring Indigenous history, languages and cultures into library spaces and to continue sharing Indigenous voices through our collections and programming. -

English Poetry 140 Poetry for Northern Learners

English Poetry 140 Poetry for Northern Learners English 140 Revised 2019 Acknowledgements The NWT Literacy Council gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance for this project from the Department of Education, Culture and Employment, GNWT. Krystine Hogan chose the poems and songs and developed the activities for this resource. Lisa Campbell did the layout and design. Contact the NWT Literacy Council to get copies of this resource. You can also download it from our website. NWT Literacy Council Box 761, Yellowknife, NT X1A 2N6 Phone toll free: 1-866-599-6758 Phone Yellowknife: (867) 873-9262 Fax: (867) 873-2176 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nwtliteracy.ca Follow us on Facebook and Twitter. We have made every effort to obtain copyright permission to reproduce the materials. We appreciate any information that will help us obtain permission for material we may not have acknowledged. Introduction Table of Contents Introduction/Poems Handouts Page #s 1. Introduction 0 handouts 2-6 What is Poetry? Why Read Poetry? Why Did We Develop a Poetry Resource? Tips for Teaching Poetry Poetry 140 2. Mother to Son 3 Handouts 7-22 Prereading Reading and Responding to the Poem Understanding the Poem 3. Northern Sky Dancers 6 Handouts 23-46 Prereading Reading and Responding to the Poem Understanding the Poem Personification 4. The Harbor 5 Handouts 47-74 Prereading Reading and Responding to the Poem Understanding the Poem Images in the Poem Sound and Meaning 5. One Drum 8 Handouts 75-111 Reviewing the Music Video Thinking about the Song’s Meaning Symbols Drums Poems 1 Poetry 140 Introduction Introduction What is Poetry? Many instructors like to have a clear and complete definition of the subject matter they are planning to teach, but poetry is not easy to define. -

Indigenous Women's Economic Security and Wellbeing

Indigenous Women’s Economic Security and Wellbeing July 2016 – Research Report Project Partners: University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills Alberta Human Services Alberta Indigenous Relations Alberta Center for Child, Family, and Community Research Research Team: Principal Investigator: Dr. Sherri Chisan Nadia Bourque Darlene Auger Lana Whiskeyjack Dale Steinhauer Carol Melnyk-Poliakiwski Sharon Steinhauer 1 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Methodology 4 Results and Analysis I. HOW DID WE SURVIVE? 9 Economy was created. It did not create us. Inclusive economics Mixed economics Reciprocity and healing Knowledge transmission Summary The disruption 12 II. HOW ARE WE SURVIVING NOW? 16 Education and training Programs and policy Funding sustainability and program measures Costs of the new economy Technology Summary III. HOW WILL WE SURVIVE IN THE FUTURE? 23 Dialogue Language and land Social economics and policy Identified actions and strategies 25 Ethical Considerations 26 Who owns the knowledge gathered in the research process? How do we know our results were valid and reliable? Axiology Limitations of the Research Conclusion 28 Appendices a. Circle questions/guidelines/community posters 30 b. List of Participating Communities 33 c. Forum poster/agenda 34 d. Consent Form 34 e. References 37 2 ABSTRACT In the summer of 2014, Blue Quills First Nations College (now University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills, UnBQ) was awarded funding from Alberta Human Services through the Alberta Centre for Child, Family, and Community Research to research the relationship between community disparity and Indigenous women’s economic security. The purpose of the study was to gain a deeper understanding of how Indigenous women, in the northeastern region of Alberta, feel and think about the economic welfare of their respective communities. -

The Key of She at the Nook Singer-Songwriters & Spoken Word

SKIRTSAFIRE’S MAINSTAGE PRODUCTION MARCH 1-11 SKIRTSAFIRE MARCH 7-17 FESTIVAL 2019 EDMONTON’S ONLY THEATRE AND MULTIDISCIPLINARY ARTS FESTIVAL FEATURING AND LIVE AT THE WINSPEAR ELEVATING THE WORK MARCH M Tick arcentre.com/tickets OF WOMEN! FESTIVAL EVENTS BY DONATION AT THE DOOR MAINSTAGE TICKETS AVAILABLE AT TIX ON THE SQUARE WELCOME TO SKIRTSAFIRE MAKING #YEGHERSTORY SINCE 2012! Welcome to SkirtsAfire 2019; our year of growth. As some venues began spilling over in 2018, we are so excited this year to be a 10 day festival and to start creeping into downtown with 3 new venues where you can see Coeur de pirate Live at the Winspear, singer-songwriters and a poet at The Nook Cafe across the street, and our SkirtsTRIVIA fundraiser in the CKUA Performance Space. As part of this expansion, we are thrilled to offer a 2nd A-Line Variety show since it’s one of our most popular events. Plus, this year it will include an expanded finale each night to end off the jam-packed events filled with amazing artists from all genres and disciplines. Back this year are all our other popular events as well: singer-songwriters in The Key of She; Words Unzipped in the Nina where you can also take in our visual art exhibit curated by Lana Whiskeyjack, Because of her, I am.; The Women’s Choir Festival, which this year will feature a Mezzo Soprano from the Edmonton Opera; Yoga in the Art; and Bellydancing at Bedouin Beats. Our theme for 2019 is Identity and we salute Marni Panas as our Honorary Skirt for 2019. -

Augmented Reality As a Resource for Indigenous–Settler Relations

International Journal of Communication 13(2019), 4530–4552 1932–8036/20190005 Sweetgrass AR: Exploring Augmented Reality as a Resource for Indigenous–Settler Relations ROB MCMAHON1 AMANDA ALMOND GREG WHISTANCE-SMITH University of Alberta, Canada DIANA STEINHAUER STEWART STEINHAUER Saddle Lake Cree Nation, Canada DIANE P. JANES Southern Alberta Institute of Technology, Canada Augmented reality (AR) is increasingly used as a digital storytelling medium to reveal place- based content, including hidden histories and alternative narratives. In the context of Indigenous–settler relations, AR holds potential to expose and challenge representations of settler colonialism while invoking relational ethics and Indigenous ways of knowing. However, it also threatens to disseminate misinformation and commodify Indigenous Knowledge. Here, we focus on collaborative AR design practices that support critical, reflective, and reciprocal relationship building by teams composed of members from Indigenous and settler communities. After a short history of Indigenous media development in Canada, we describe how we operationalized a participatory AR design process to strengthen Indigenous–settler relations. We document a series of iterative design steps that teams can use to work through Rob McMahon: [email protected] Amanda Almond: [email protected] Greg Whistance-Smith: [email protected] Diana Steinhauer: [email protected] Stewart Steinhauer: [email protected] Diane P. Janes: [email protected] Date submitted: 2019–03–14 1 We thank colleagues at the University of Alberta who advised us: Patricia Makokis, Fay Fletcher, Jason Daniels, Lana Whiskeyjack, and Jennifer Ward. Jennifer Wemigwans, Jane Anderson, Catherine Bell, and the Alberta First Nations Information Governance Centre also provided support and guidance for this project. -

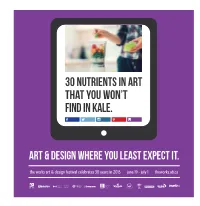

30 Nutrients in Art That You Won't Find in Kale

30 nutrients in art that you won’t find in kale. ART & DESIGN WHERE YOU LEAST EXPECT IT. the works art & design festival celebrates 30 years in 2015 june 19 - july 1 theworks.ab.ca THANK YOU 1 FOUNDING SPONSOR VENUE SUPPORTERS (Cont’d) ENBRIDGE ART INTERNS: The Works Art & Design Festival Downtown Business Association of Edmonton Unit B WORKS TO WORK 10635-95 Street NW Edmonton, AB T5H 2C3 Edmonton Chamber of Commerce Tel: 780-426-2122 SPONSORS Francis Winspear Centre for Music Production Team Fax: 780-426-4673 RBC Building Supervisor Laura Campbell During Festival, call Information Services on Churchill Square The City of Edmonton Melcor Developments Ltd. Coordinator Kasie Campbell at: 780-818-4420 Edmonton Arts Council [email protected] Alberta Foundation for the Arts Assistant Tegan Bowers CONTRIBUTORS www.theworks.ab.ca Canadian Heritage, Government of Canada Assistant Natalie Castrogiovanni Alberta Craft Council Assistant Matthew Carr vol.30, 2015 Bikeology: Festival Assistant Kezia Rooke SPONSORING PARTNERS, EDUCATION The Works takes an entire year to produce with 3 full- Enbridge Pipelines Inc. City Centre Mall Assistant Evan Terlesky time year round staff, 3 part-time staff, and 50 Seasonal/ Edmonton Business Council for Visual Arts Discount Flags contract workers. Each year, hundreds of individuals The Works Art Festival Fund at Edmonton Community Foundation Edmonton Bicycle Commuters Society Curatorial Team contribute over five thousand volunteer hours to The Edmonton Cash Register Co. Ltd. Supervisor Lucille Frost Works -

Cree Language) Kyle Napier and Lana Whiskeyjack

Document generated on 10/02/2021 9:56 a.m. Engaged Scholar Journal Community-Engaged Research, Teaching and Learning wahkotowin: Reconnecting to the Spirit of nêhiyawêwin (Cree Language) Kyle Napier and Lana Whiskeyjack Indigenous and Trans-Systemic Knowledge Systems Article abstract Volume 7, Number 1, 2021 The Spirit of the Language project looks to the Spirit of nêhiyawêwin (Cree language), sources of disconnection between nêhiyawak (Cree people) in URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1078626ar Treaty 6 and the Spirit of nêhiyawêwin, and the process of reconnection to the DOI: https://doi.org/10.15402/esj.v7i1.69979 Spirit of the language as voiced by nêhiyawak. The two researchers behind this project are nêhiyaw language-learners who identify as insider-outsiders in this See table of contents work. The work is founded in Indigenous Research Methodologies, with a particular respect to ceremony, community protocol, consent, and community participation, respect and reciprocity. We identified the Spirit of the language as having three distinct strands: history, harms, and healing. The Spirit of Publisher(s) Indigenous languages is dependent on its history of land, languages, and laws. University of Saskatchewan We then identified the harms or catalysts of disconnect from the Spirit of the language as colonization, capitalism, and Christianity. The results of our community work have identified the methods for healing, or reconnecting to ISSN the Spirit of language, by way of autonomy, authority, and agency. 2369-1190 (print) 2368-416X (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Napier, K. & Whiskeyjack, L. (2021). wahkotowin: Reconnecting to the Spirit of nêhiyawêwin (Cree Language). -

Thursday, November 20, 2014

Thursday, November 20, 2014 7:15 Registration and Continental Breakfast Colony Ballroom and Foyer 8:00 Opening Ceremony and Welcome Colony Ballroom 8:30 Justice Murray Sinclair: Colony Ballroom Truth and Reconciliation Commission 9:30 Dr. Evan Adams: Transforming Systems, Transforming Ourselves – an Update on the First Nations Health Authority in BC Colony Ballroom 10:15 Refreshment Break with Posters and Exhibits 10:30 Workshop Session #1 Room Suicide W01 Complementary Competencies Through Lombard Prevention Collaboration for First Nations and Mainstream Addictions 2nd Floor Managers and Workers Carol Hopkins, Robert Eves, Raymond Deleary National Native Addictions Partnership Foundation, Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse Mental Health W02 Connecting the Dots: An Innovative Urban Aboriginal St. David Mental Health Project North Jessa Williams, Johanna Denduyf 3rd Floor Canadian Mental Health Association British Columbia Division, British Columbia Association of Aboriginal Friendship Centres Women's W03 Supporting First Nations, Métis and Inuit Women to St. David Health Engage in Shared Decision Making: A Skill Building South Workshop 3rd Floor Janet Elizabeth Jull, Minwaashin Lodge, Dawn Stacey University of Ottawa, Institute of Population Health, Minwaashin Lodge - The Aboriginal Women's Support Centre, University of Ottawa Traditional W05 Atikowisi miýw-ay¯awin, Ascribed Health and Elm Wellness, to Kaskitamasowin miýw-ay¯awin¯, Achieved 2nd Floor Health and Wellness: Shifting the Paradigm Madeleine Dion Stout, Elder Food security -

IFNMI17-114 Visual Expression and Creating Relations - Confronting History: Resilience and Reconciliation

IFNMI17-114 Visual Expression and Creating Relations - Confronting History: Resilience and Reconciliation Presented By: Lana Whiskeyjack & Alsena White Date(s): Session Location: Registration Fee: Tuesday, April 04, 2017 St. Paul Regional High School Room 220 $105.00 9:30 AM - 3:00 PM 4701 - 44 Street, St. Paul, AB Audience: Grade Level: Special Notes: Registration fee includes a continental breakfast and lunch. About the Session: This interactive workshop of confronting history will begin with a traditional Cree introduction of the facilitator Lana Whiskeyjack. Lana will weave her personal stories and mini-art breaks throughout a historical presentation of Indigenous worldviews and exploring the relationship between the Indigenous Peoples and the Canadian government. The second part of the workshop will be a presentation of transcending Indian Residential School (IRS) trauma through a documentary film called Gently Whispering Back the Circle (2013). The day will close with a circle dialogue on the presentations and reconciliation as understood by each of the participants. Participants are encouraged to bring paper/sketchbook and pen/pencils/crayons to help process the conversation. This learning opportunity is being provided through a grant from Alberta Education. About the Presenter(s): Lana Whiskeyjack & Alsena White Lana Whiskeyjack ayisîyiniw ôta asiskiy - I am human from this earth. Lana is a multidisciplinary artist and educator and member of the Saddle Lake Cree Nation, Treaty 6 Territory, Canada. Lana began her artistic training as a toddler drawing on blank empty walls followed by formal training in ceramic sculpture at Red Deer College (1996), University of Alberta (1999) and environmental sculpture at Pont Aven School of Art in France (2000).