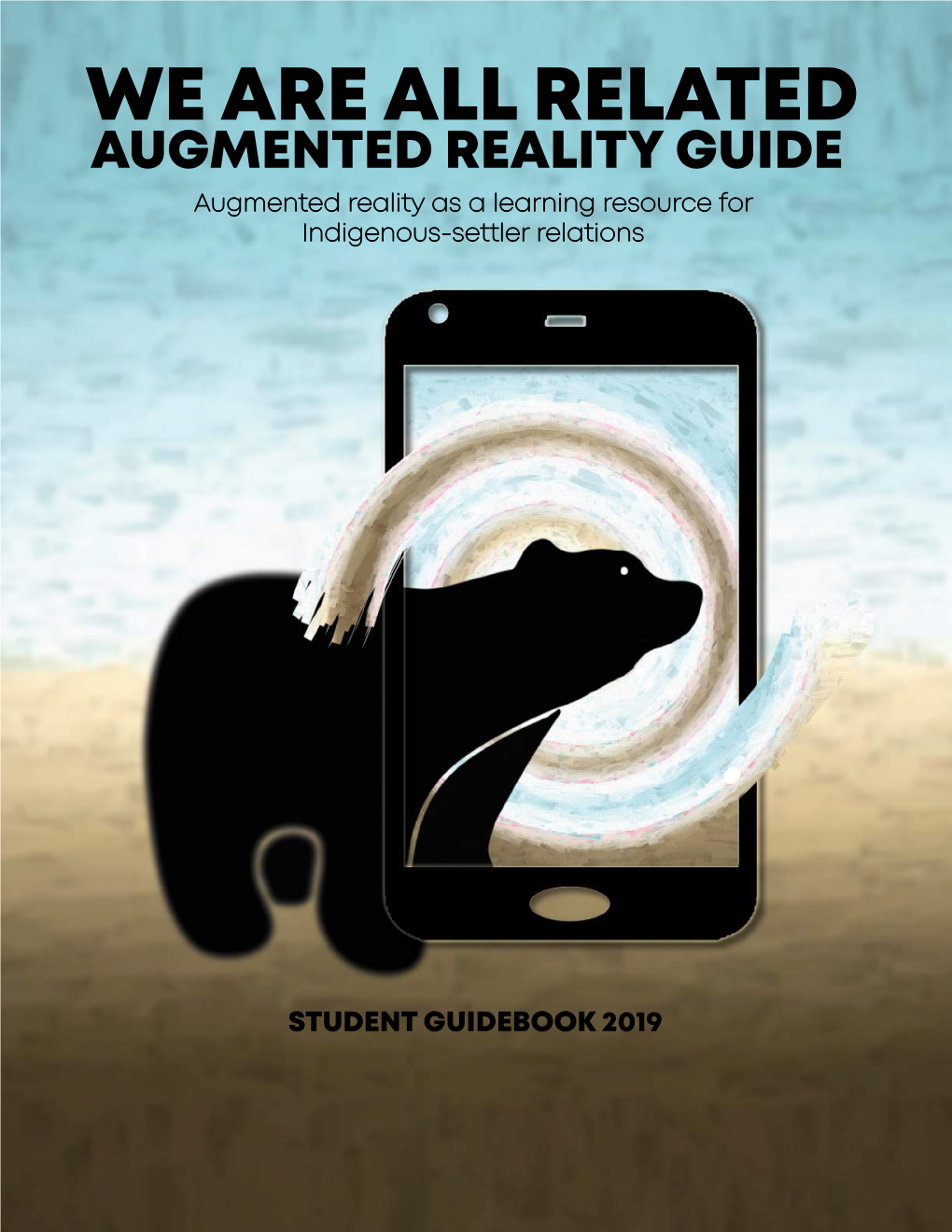

WE ARE ALL RELATED AUGMENTED REALITY GUIDE Augmented Reality As a Learning Resource for Indigenous-Settler Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chief Raymond Arcand Alan Paul Edwin Paul CEO Alexander First Nation Alexander First Nation IRC PO Box 3419 PO Box 3510 Morinville, AB T8R 1S3 Morinville, AB T8R 1S3

Chief Raymond Arcand Alan Paul Edwin Paul CEO Alexander First Nation Alexander First Nation IRC PO Box 3419 PO Box 3510 Morinville, AB T8R 1S3 Morinville, AB T8R 1S3 Chief Cameron Alexis Rosaleen Alexis Chief Tony Morgan Alexis Nakota Sioux First Nation Gitanyow First Nation PO Box 7 PO Box 340 Glenevis, AB T0E 0X0 Kitwanga, BC V0J 2A0 Fax: (780) 967-5484 Chief Alphonse Lameman Audrey Horseman Beaver Lake Cree Nation HLFN Industrial Relations Corporation PO Box 960 Box 303 Lac La Biche, AB T0A 2C0 Hythe, AB T0H 2C0 Chief Don Testawich Chief Rose Laboucan Ken Rich Driftpile First Nation Duncan’s First Nation General Delivery PO Box 148 Driftpile, AB T0G 0V0 Brownvale, AB T0H 0L0 Chief Ron Morin Chief Rick Horseman Irene Morin Arthur Demain Enoch Cree Nation #440 Horse Lake First Nation PO Box 29 PO Box 303 Enoch, AB T7X 3Y3 Hythe, AB T0H 2C0 Chief Thomas Halcrow Kapawe’no First Nation Chief Daniel Paul PO Box 10 Paul First Nation Frouard, AB T0G 2A0 PO Box 89 Duffield, AB T0E 0N0 Fax: (780) 751-3864 Chief Eddy Makokis Chief Roland Twinn Saddle Lake Cree Nation Sawridge First Nation PO Box 100 PO Box 3236 Saddle Lake, AB T0A 3T0 Slave Lake, AB T0G 2A0 Chief Richard Kappo Chief Jaret Cardinal Alfred Goodswimmer Sucker Creek First Nation Sturgeon Lake Cree PO Box 65 PO Box 757 Enilda, AB T0G 0W0 Valleyview, AB T0H 3N0 Chief Leon Chalifoux Chief Leonard Houle Ave Dersch Whitefish Lake First Nation #128 Swan River First Nation PO Box 271 PO Box 270 Goodfish Lake, AB T0A 1R0 Kinuso, AB T0G 0W0 Chief Derek Orr Chief Dominic Frederick Alec Chingee Lheidli T’enneh McLeod Lake Indian Band 1041 Whenun Road 61 Sekani Drive, General Delivery Prince George, BC V2K 5X8 McLeod Lake, BC V0J 2G0 Grand Chief Liz Logan Chief Norman Davis Kieran Broderick/Robert Mects Doig River First Nation Treaty 8 Tribal Association PO Box 56 10233 – 100th Avenue Rose Prairie, BC V0C 2H0 Fort St. -

Annual Report Still from Infinitude by Scott Portingale, Photo Supplied

2015 annual report Still from Infinitude by Scott Portingale, photo supplied Alberta Cantonese Opera Festival presents War Drum in Golden Mountain, photo supplied “CONFUSEMENT” by Nina Haggerty artist Scott Berry, Michalene Giesbrecht, Sandra Olarte, and Stephanie Gruson in photo by Jenna Turner Firefly Theatre & Circus’ “The Playground”, photo by Studio E Photography 2015 annual report The Edmonton Arts Council The Edmonton Arts Council is a not-for-profit society and charitable organization that supports and promotes the arts community in Edmonton. The EAC works to increase the profile and involvement of arts and culture in all aspects of our community life through activities that: Invest Represent Build Create in Edmonton Edmonton’s arts partnerships and awareness of festivals, arts community to initiate projects the quality, organizations government and that strengthen variety, and and individual other agencies our community. value of artistic artists through and provide work produced municipal, expert advice on in Edmonton. corporate, and issues that affect private funding. the arts. 1 "Navigating Boundaries” by Kelsey Stephenson and Jes McCoy Reconciliation in Solidarity Edmonton (RISE) Community Heart Garden at Harcourt House, photo by Kelsey Stephenson installed at City Hall, photo by Gibby Davis Angela Gladue, Lana Whiskeyjack and Logan Alexis 2 Drummers at Channeling Connections, photo by Brad Crowfoot Katherine Kerr and Edmonton Community Foundation’s Alex Draper, Annette Aslund and Jenna Turner, photo by Brad Crowfoot photo -

Superintendent's Memo

Superintendent’s Memo For the Week of March 13th -17th, 2017 FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT... This month our trustee showcase in “Meet the Trustee” is Lanie Parr. Lanie was INSIDE THIS ISSUE elected in 2010 and will have served the students of BTPS for seven years at the end of this term in October! Technology ........................... 2 Curriculum ............................ 3 Lanie Parr – A Little Bit About Me HR/Payroll.......……….............4 I was born in Port Alberni, BC, but moved Extras .................................... 5 to Calgary to attend school. I finished Around BTPS………………….6-9 school in Calgary and went on to study Earth Sciences at the University of Calgary, graduating with a Bachelor of Science. During University, I was fortunate to be able to study abroad, completing a Field School in Question of the week is on Page 5! New prizes this year!!! Geography in the Mediterranean, introducing me to a love of travel. After graduation, I spent a year living and working in Vancouver and doing some fieldwork in Northern BC and the Yukon, but eventually moved back to Alberta. I then headed off backpacking in Asia for four months before returning to work for a pipeline company in Email: [email protected] Alberta and the US. In the meantime, I met my future husband, and we now farm near Dewberry and are raising three busy, active daughters. We love the outdoors, the mountains and are avid COMMENTS ABOUT snowboarders and skiers! THIS NEWSLETTER? Lanie is the Vice Chair of the Board of Buffalo Trail Public Schools. Please send your comments or She serves on the Policy Committee and is a Director for the Public suggestions to [email protected] School Boards Association of Alberta. -

SKIPP Virtual Colloquium Event Transcript Friday June 12, 2020 - Connecting with Indigenous-Engaged Research, Research Creation, and Scholarship in the Fine Arts

SKIPP Virtual Colloquium Event Transcript Friday June 12, 2020 - Connecting with Indigenous-engaged Research, Research Creation, and Scholarship in the Fine Arts Thomas Barker: Hello everyone, welcome to the Virtual Colloquium on Indigenous-engaged Research, my name is Tom Barker and I'm a professor in the Communication and Technology Master's Program. I will be your host today. Just as a reminder, we will be recording those presenters today who have given us their permission to do so. For our participants, please keep your video off and your microphones muted, we have a lot of participants we find that that practice works best for us. If you have any trouble viewing any of the PowerPoint presentations today, simply click the “view options” at the top of your screen and select “fit to screen,” that will ensure that your presentation is properly sized for your screen. Our technical moderator today is Rebecca Gray, so if you have any technical questions, please send her a message in the chat. You can click on Rebecca's name in the chat window and privately to her. Our format today is to invite our speakers to share their stories and then we will open it up for discussion. So if you don't mind, hold all your questions until the presentations are complete. Before we move on to our first presenter I would like to remind you that this colloquium is coming from the University of Alberta in Edmonton, we are located on Treaty 6 territory, traditional homelands of the Métis and Papaschase Cree people. -

Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta Community Profiles

For additional copies of the Community Profiles, please contact: Indigenous Relations First Nations and Metis Relations 10155 – 102 Street NW Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4G8 Phone: 780-644-4989 Fax: 780-415-9548 Website: www.indigenous.alberta.ca To call toll-free from anywhere in Alberta, dial 310-0000. To request that an organization be added or deleted or to update information, please fill out the Guide Update Form included in the publication and send it to Indigenous Relations. You may also complete and submit this form online. Go to www.indigenous.alberta.ca and look under Resources for the correct link. This publication is also available online as a PDF document at www.indigenous.alberta.ca. The Resources section of the website also provides links to the other Ministry publications. ISBN 978-0-7785-9870-7 PRINT ISBN 978-0-7785-9871-8 WEB ISSN 1925-5195 PRINT ISSN 1925-5209 WEB Introductory Note The Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta: Community Profiles provide a general overview of the eight Metis Settlements and 48 First Nations in Alberta. Included is information on population, land base, location and community contacts as well as Quick Facts on Metis Settlements and First Nations. The Community Profiles are compiled and published by the Ministry of Indigenous Relations to enhance awareness and strengthen relationships with Indigenous people and their communities. Readers who are interested in learning more about a specific community are encouraged to contact the community directly for more detailed information. Many communities have websites that provide relevant historical information and other background. -

Abuse of Power in Relationships and Sexual Health

Child Abuse & Neglect 58 (2016) 12–23 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Child Abuse & Neglect Research article Abuse of power in relationships and sexual health a,∗ b b,1 c Dionne Gesink , Lana Whiskeyjack , Terri Suntjens , Alanna Mihic , d,2 Priscilla McGilvery a Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, 155 College St., 6th Floor, Toronto, Ontario M5T 3M7, Canada b Blue Quills First Nations College, Box 279, St. Paul, Alberta T0A 3A0, Canada c University of Toronto, 155 College St., Toronto, Ontario M5T 3M7, Canada d Saddle Lake Health Center, P.O. Box 160, Saddle Lake, Alberta T0A 3T0, Canada a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: STI rates are high for First Nations in Canada and the United States. Our objective was to Received 23 January 2016 understand the context, issues, and beliefs around high STI rates from a nêhiyaw (Cree) Received in revised form 31 May 2016 perspective. Twenty-two in-depth interviews were conducted with 25 community partici- Accepted 2 June 2016 pants between March 1, 2011 and May 15, 2011. Interviews were conducted by community researchers and grounded in the Cree values of relationship, sharing, personal agency and Keywords: relational accountability. A diverse purposive snowball sample of community members Abuse of power were asked why they thought STI rates were high for the community. The remainder of Sexually transmitted infections the interview was unstructured, and supported by the interviewer through probes and Sexual abuse sharing in a conversational style. -

Indian Band Revenue Moneys Order Décret Sur Les Revenus Des Bandes D’Indiens

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Indian Band Revenue Moneys Décret sur les revenus des Order bandes d’Indiens SOR/90-297 DORS/90-297 Current to October 11, 2016 À jour au 11 octobre 2016 Last amended on December 14, 2012 Dernière modification le 14 décembre 2012 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (3) of the Legislation Revision and Les paragraphes 31(1) et (3) de la Loi sur la révision et la Consolidation Act, in force on June 1, 2009, provide as codification des textes législatifs, en vigueur le 1er juin follows: 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published consolidation is evidence Codifications comme élément de preuve 31 (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or consolidated 31 (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou d'un règlement regulation published by the Minister under this Act in either codifié, publié par le ministre en vertu de la présente loi sur print or electronic form is evidence of that statute or regula- support papier ou sur support électronique, fait foi de cette tion and of its contents and every copy purporting to be pub- loi ou de ce règlement et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire lished by the Minister is deemed to be so published, unless donné comme publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi the contrary is shown. publié, sauf preuve contraire. -

Table of Contents

Post-Secondary Education Gathering October 15, 2018 Pinnacle Hotel Harbourfront Table of Contents Document Description Page Tab 1: WELCOME AND REVIEW OF DRAFT AGENDA 1.0 Draft Agenda 1 Tab 2: PARTNERSHIPS 2.0 Aboriginal Post-Secondary Education and Training Memorandum of Understanding 2 2.1 ABCDE-FNESC-IAHLA Memorandum of Understanding 3 2.2 AEST-FNESC/IAHLA Protocol Agreement 5 Tab 3: CONTEXT Summary of United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 3.0 Articles and Truth and Reconciliation Calls to Action related to Post-Secondary 12 Education and Training Aboriginal Post-Secondary Education and Training Policy Framework 2020 Vision 3.1 15 for the Future 3.2 BC First Nations PSE Student Data Summary 56 Tab 4: BC PSE MODEL CONSIDERATIONS 4.0 Graphic BC-Specific PSE Funding Model 59 Tab 5: BC CONTEXT Honourable Minister Melanie Mark (Advanced Education, Skills and Training) 5.0 60 Mandate Letter 5.1 Honourable Minister Rob Fleming (Education) Mandate Letter 63 Draft Principles that Guide the Province of BC’s Relationship with Indigenous 5.2 66 Peoples Letter to First Nations Leadership Council Members from Honourable Minister 5.3 74 Scott Fraser RE: Endorsement of Commitment Document Aboriginal Student Data Report: “Aboriginal Learners in British Columbia’s Public 5.4 77 Post-Secondary System” Tab 6: NATIONAL CONTEXT 6.0 Honourable Minister Jane Philpott (Indigenous Services Canada) Mandate Letter 129 Honourable Minister Carolyn Bennett (Crown-Indigenous Relations Canada) 6.1 134 Mandate Letter Principles Respecting the -

0.41 MB Saddle Lake Lateral

450 - 1 Street SW Calgary, Alberta T2P 5H1 Tel: (403) 920-7425 Fax: (403) 920-2347 E-mail: [email protected] November 30, 2020 Filed Electronically Canada Energy Regulator Suite 210, 517 Tenth Avenue SW Calgary, AB T2R 0A8 Attention: Mr. Jean-Denis Charlebois, Secretary of the Commission Dear Mr. Charlebois: Re: NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. (NGTL) Saddle Lake Lateral Loop (Cold Lake Section) Project (Project) Order XG-016-2020 (Order) Condition 4: Commitments Tracking Table No. 4 File No.: OF-Fac-Gas-N081-2019-11 01 Pursuant to Condition 4(b), NGTL submits the Project Commitments Tracking Table No. 4 for the month of November. For ease of reference, modifications to the Commitments Tracking Table have been blacklined. As required, NGTL will notify all potentially affected Indigenous peoples who have expressed interest in the Project, and post the Commitments Tracking Table to TC Energy’s pipeline projects webpage for public viewing at the following link: https://www.tcenergy.com/operations/natural-gas/saddle-lake-lateral-loop/ If the CER requires additional information with respect to this filing, please contact me by phone at (403) 920-7425 or by email at [email protected] Yours truly, NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. Originally signed by Kenneth Pountney Regulatory Project Manager Regulatory Facilities, Canadian Natural Gas Pipelines Enclosure cc: Erin Estoy, Canada Energy Regulator Condition 4 NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. Commitments Tracking Table No. 4 – November Saddle Lake Lateral Loop (Cold Lake Section) XG-016-2020 Table 1: Commitment Tracking Table No. 4 - November Document Commitment Commitment References Number To Category Description of Commitment Source (CER Filing ID) Status Project Phase Accountability Comments Order XG-016-2020 CER Order Conditions NGTL must comply with all of the conditions contained in Order XG-016-2020 C07372 Ongoing Pre-Construction Regulatory Project Manager this Order unless the Commission otherwise directs. -

CHILDREN's SERVICES DELIVERY REGIONS and INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES

CHILDREN'S SERVICES DELIVERY REGIONS and INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES DELEGATED FIRST NATION AGENCIES (DFNA) 196G Bistcho 196A 196D Lake 225 North Peace Tribal Council . NPTC 196C 196B 196 96F Little Red River Cree Nation Mamawi Awasis Society . LRRCN WOOD 1 21 223 KTC Child & Family Services . KTC 3 196E 224 214 196H Whitefish Lake First Nation #459 196I Child and Family Services Society . WLCFS BUFFALO Athabasca Tribal Council . ATC Bigstone Cree First Nation Child & Family Services Society . BIGSTONE 222 Lesser Slave Lake Indian Regional Council . LSLIRC 212 a Western Cree Tribal Council 221 e c k s a a 211 L b Child, Youth & Family Enhancement Agency . WCTC a NATIONAL th Saddle Lake Wah-Koh-To-Win Society . SADDLE LAKE 220 A 219 Mamowe Opikihawasowin Tribal Chiefs 210 Lake 218 201B Child & Family (West) Society . MOTCCF WEST 209 LRRCN Claire 201A 163B Tribal Chief HIGH LEVEL 164 215 201 Child & Family Services (East) Society . TCCF EAST 163A 201C NPTC 162 217 201D Akamkisipatinaw Ohpikihawasowin Association . AKO 207 164A 163 PARK 201E Asikiw Mostos O'pikinawasiwin Society 173B (Louis Bull Tribe) . AMOS Kasohkowew Child & Wellness Society (2012) . KCWS 201F Stoney Nakoda Child & Family Services Society . STONEY 173A 201G Siksika Family Services Corp. SFSC 173 Tsuu T'ina Nation Child & Family Services Society . TTCFS PADDLE Piikani Child & Family Services Society . PIIKANI PRAIRIE 173C Blood Tribe Child Protection Corp. BTCP MÉTIS SMT. 174A FIRST NATION RESERVE(S) 174B 174C Alexander First Nation . 134, 134A-B TREATY 8 (1899) Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation . 133, 232-234 174D 174 Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation . 201, 201A-G Bearspaw First Nation (Stoney) . -

Alberta First Nations Contact Listing (May 2019)

Postal Band Office Treaty First Nation Title First Name Last Name Mailing Address City Province Code Phone #'s Fax # Appeal period End Date 6 Alexander First Nation Chief Kurt Burnstick PO Box 3419 Morinville Alberta T8R 1S3 780-939-5887 780-939-6166 6 Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation Chief Clayton (Tony) Alexis PO Box 7 Glenevis Alberta T0E 0X0 780-967-2225 780-967-5484 8 Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation Chief Allan Adam PO Box 366 Fort Chipewyan Alberta T0P 1B0 780-697-3730 780-697-3500 7 Bearspaw First Nation Chief Darcy Dixon PO Box 40 Morley Alberta T0L 1N0 403-881-2660 403-881-2676 8 Beaver First Nation Chief Trevor Mercredi PO Box 270 High Level Alberta T0H 1Z0 780-927-3544 780-927-4064 6 Beaver Lake Cree Nation Chief Germaine Anderson PO Box 960 Lac La Biche Alberta T0A 2C0 780-623-4549 780-623-4523 8 Bigstone Cree Nation Chief Silas Yellowknee PO Box 960 Wabasca Alberta T0G 2K0 780-891-3836 780-891-3942 7 Blood Tribe (Kainai Nation) Chief Roy Fox PO Box 60 Stand Off Alberta T0L 1Y0 403-737-3753 403-737-2336 7 Chiniki First Nation Chief Aaron Young PO Box 40 Morley Alberta T0L 1N0 403-881-2265 403-881-2676 8 Chipewyan Prairie First Nation Chief Vern Janvier General Delivery Chard Alberta T0P 1G0 780-559-2259 780-559-2213 6 Cold Lake First Nations Chief Bernice Martial Box 1769 Cold Lake Alberta T9M 1P4 780-594-7183 780-594-3577 8 Dene Tha' First Nation Chief James Ahnassay PO Box 120 Chateh Alberta T0H 0S0 780-321-3775 780-321-3886 8 Driftpile Cree Nation Chief Dwayne Laboucan Box 30 Driftpile Alberta T0G 0V0 780-355-3868 780-355-3650 -

2004-2009 Strategic Plan Entire

June 21, 2004 The Honourable Diane McGifford Minister of Advanced Education and Training 156 Legislative Building Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 0V8 Dear Minister McGifford, I am pleased to submit Bringing Together the Past, Present and Future: Building a System of Post-Secondary Education in Northern Manitoba, a Five Year Strategic Plan for the University College of the North as the final report for the work of the UCN Implementation Team. Many people provided support to the UCN Implementation Team, including the members of the Steering Committee, the Elders’ Consultations, the Focus Groups, the people we met during presentations, the staff of Keewatin Community College and Inter-Universities North, KCC President Tony Bos as well as many others in the north. The senior staff of Advanced Education and Training, and other individuals within government have also been a support to the Team in many ways. There is still much to be done. The work is just beginning for the innovation and creativity to be put to use, to implement the visions and dreams of many people. The future is where the challenge will be. With continued cooperation and support, all those dreams of meeting the post-secondary educational needs of northern people, especially the young people, can be met. In working together we can do so much. Yours Sincerely, Don Robertson Chairperson, University College of the North Implementation Team University College of the North Implementation Team Don Robertson, Chair Veronica Dyck, Manager John Burelle Peter Geller Gina Guiboche Heather McRae