DROUGHT: a Litmus Test for Watershed Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cpmg / Ka / Bg-Gpo/13/2003-2005

The Karnataka Value Added Tax Act, 2003 Act 32 of 2004 Keyword(s): Assessment, Business, Capital Goods, To Cultivate Personally, Dealer, Export, Goods Vehicle, Import, Input Tax, Maximum Retail Price, Output Tax, Place of Business, Published, Registered Dealer, Return, Sale, State Representative, Taxable Sale, Tax Invoice, Tax Period, Taxable Turnover, Total Turnover, Works Contract Amendments appended; 5 of 2009, 32 of 2013, 54 of 2013, 5 of 2015 DISCLAIMER: This document is being furnished to you for your information by PRS Legislative Research (PRS). The contents of this document have been obtained from sources PRS believes to be reliable. These contents have not been independently verified, and PRS makes no representation or warranty as to the accuracy, completeness or correctness. In some cases the Principal Act and/or Amendment Act may not be available. Principal Acts may or may not include subsequent amendments. For authoritative text, please contact the relevant state department concerned or refer to the latest government publication or the gazette notification. Any person using this material should take their own professional and legal advice before acting on any information contained in this document. PRS or any persons connected with it do not accept any liability arising from the use of this document. PRS or any persons connected with it shall not be in any way responsible for any loss, damage, or distress to any person on account of any action taken or not taken on the basis of this document. 301 KARNATAKA ACT NO. 32 OF 2004 THE KARNATAKA VALUE ADDED TAX ACT, 2003 Arrangement of Sections Sections: Chapter I Introduction 1. -

Sri Ramakrishna & His Disciples in Orissa

Preface Pilgrimage places like Varanasi, Prayag, Haridwar and Vrindavan have always got prominent place in any pilgrimage of the devotees and its importance is well known. Many mythological stories are associated to these places. Though Orissa had many temples, historical places and natural scenic beauty spot, but it did not get so much prominence. This may be due to the lack of connectivity. Buddhism and Jainism flourished there followed by Shaivaism and Vainavism. After reading the lives of Sri Chaitanya, Sri Ramakrishna, Holy Mother and direct disciples we come to know the importance and spiritual significance of these places. Holy Mother and many disciples of Sri Ramakrishna had great time in Orissa. Many are blessed here by the vision of Lord Jagannath or the Master. The lives of these great souls had shown us a way to visit these places with spiritual consciousness and devotion. Unless we read the life of Sri Chaitanya we will not understand the life of Sri Ramakrishna properly. Similarly unless we study the chapter in the lives of these great souls in Orissa we will not be able to understand and appreciate the significance of these places. If we go on pilgrimage to Orissa with same spirit and devotion as shown by these great souls, we are sure to be benefited spiritually. This collection will put the light on the Orissa chapter in the lives of these great souls and will inspire the devotees to read more about their lives in details. This will also help the devotees to go to pilgrimage in Orissa and strengthen their devotion. -

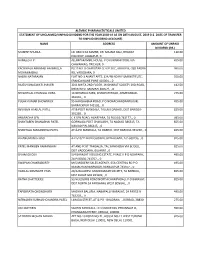

APL Details Unclaimed Unpaid Interim Dividend F.Y. 2019-2020

ALEMBIC PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID INTERIM DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2019‐20 AS ON 6TH APRIL, 2020 (I.E. DATE OF TRANSFER TO UNPAID DIVIDEND ACCOUNT) NAME ADDRESS AMOUNT OF UNPAID DIVIDEND (RS.) MUKESH SHUKLA LIC CBO‐3 KA SAMNE, DR. MAJAM GALI, BHAGAT 200.00 COLONEY, JABALPUR, 0 HAMEED A P . ALUMPARAMBIL HOUSE, P O KURANHIYOOR, VIA 900.00 CHAVAKKAD, TRICHUR, 0 RAJESH BHAGWATI JHAVERI 30 B AMITA 2ND FLOOR, JAYBHARAT SOCIETY 3RD ROAD, 750.00 KHAR WEST MUMBAI 400521, , 0 NALINI NATARAJAN FLAT NO‐1 ANANT APTS, 124/4B NEAR FILM INSTITUTE, 1000.00 ERANDAWANE PUNE 410004, , 0 ANURADHA SEN C K SEN ROAD, AGARPARA, 24 PGS (N) 743177, , 0 900.00 SWAPAN CHAKRABORTY M/S MODERN SALES AGENCY, 65A CENTRAL RD P O 900.00 NONACHANDANPUKUR, BANACKPUR 743102, , 0 PULAK KUMAR BHOWMICK 95 HARISHABHA ROAD, P O NONACHANDANPUKUR, 900.00 BARRACKPUR 743102, , 0 JOJI MATHEW SACHIN MEDICALS, I C O JUNCTION, PERUNNA P O, 1000.00 CHANGANACHERRY, KERALA, 100000 MAHESH KUMAR GUPTA 4902/88, DARYA GANJ, , NEW DELHI, 110002 250.00 M P SINGH UJJWAL LTD SHASHI BUILDING, 4/18 ASAF ALI ROAD, NEW 900.00 DELHI 110002, NEW DELHI, 110002 KOTA UMA SARMA D‐II/53 KAKA NAGAR, NEW DELHI INDIA 110003, , NEW 500.00 DELHI, 110003 MITHUN SECURITIES PVT LTD 1224/5 1ST FLOOR SUCHET CHAMBS, NAIWALA BANK 50.00 STREET, KAROL BAGH, NEW DELHI, 110005 ATUL GUPTA K‐2,GROUND FLOOR, MODEL TOWN, DELHI, DELHI, 1000.00 110009 BHAGRANI B‐521 SUDERSHAN PARK, MOTI NAGAR, NEW DELHI 1350.00 110015, NEW DELHI, 110015 VENIRAM J SHARMA G 15/1 NO 8 RAVI BROS, NR MOTHER DAIRY, MALVIYA 50.00 -

Cummins India Limited Annual Report 2018-19

Annual Report 2018 - 19 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAIRMAN’S LETTER 1 TO THE SHAREHOLDERS 2 MANAGING DIRECTOR’S LETTER 2 TO THE SHAREHOLDERS 4 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 3 12 DIRECTORS’ REPORT AND 4 ANNEXURE 14 STANDALONE AND CONSOLIDATED 5 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 105 BUSINESS RESPONSIBILITY 6 REPORT 240 1 Mark Levett Chairman, Cummins India Limited Dear Shareholders, I begin this letter with a sense of pride about being a Cummins in India has been a significant contributor not part of Cummins, an organization whose mission is just to Cummins Inc. but also to the Indian economy to make people’s lives better. While creating financial through the innovative and dependable solutions they stability and wealth for our stakeholders is essential to have been providing for over five decades. India is our future, doing so sustainably is equally important also one of the key emerging markets and like all other and it is this belief that has been central to the success markets, has its own unique set of challenges. With strategy of Cummins. stringent emission norms and massive infrastructure growth posing as the primary drivers of the economy, It has been a year since I have taken on this role with we look at these as an opportunity to provide even better Cummins India and it has been an exciting journey solutions that meet the diverse needs of our customers. topped with remarkable results. Last year, I shared with you the Mission, Vision and Values that serve I am confident of our future as we move ahead. Our as our guiding principles in delivering value to all our strengths remain. -

Name Address Amount of Unpaid Dividend (Rs.) Mukesh Shukla Lic Cbo‐3 Ka Samne, Dr

ALEMBIC PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2018‐19 AS ON 28TH AUGUST, 2019 (I.E. DATE OF TRANSFER TO UNPAID DIVIDEND ACCOUNT) NAME ADDRESS AMOUNT OF UNPAID DIVIDEND (RS.) MUKESH SHUKLA LIC CBO‐3 KA SAMNE, DR. MAJAM GALI, BHAGAT 110.00 COLONEY, JABALPUR, 0 HAMEED A P . ALUMPARAMBIL HOUSE, P O KURANHIYOOR, VIA 495.00 CHAVAKKAD, TRICHUR, 0 KACHWALA ABBASALI HAJIMULLA PLOT NO. 8 CHAROTAR CO OP SOC, GROUP B, OLD PADRA 990.00 MOHMMADALI RD, VADODARA, 0 NALINI NATARAJAN FLAT NO‐1 ANANT APTS, 124/4B NEAR FILM INSTITUTE, 550.00 ERANDAWANE PUNE 410004, , 0 RAJESH BHAGWATI JHAVERI 30 B AMITA 2ND FLOOR, JAYBHARAT SOCIETY 3RD ROAD, 412.50 KHAR WEST MUMBAI 400521, , 0 SEVANTILAL CHUNILAL VORA 14 NIHARIKA PARK, KHANPUR ROAD, AHMEDABAD‐ 275.00 381001, , 0 PULAK KUMAR BHOWMICK 95 HARISHABHA ROAD, P O NONACHANDANPUKUR, 495.00 BARRACKPUR 743102, , 0 REVABEN HARILAL PATEL AT & POST MANDALA, TALUKA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐ 825.00 391230, , 0 ANURADHA SEN C K SEN ROAD, AGARPARA, 24 PGS (N) 743177, , 0 495.00 SHANTABEN SHANABHAI PATEL GORWAGA POST CHAKLASHI, TA NADIAD 386315, TA 825.00 NADIAD PIN‐386315, , 0 SHANTILAL MAGANBHAI PATEL AT & PO MANDALA, TA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐391230, , 0 825.00 B HANUMANTH RAO 4‐2‐510/11 BADI CHOWDI, HYDERABAD, A P‐500195, , 0 825.00 PATEL MANIBEN RAMANBHAI AT AND POST TANDALJA, TAL.SANKHEDA VIA BODELI, 825.00 DIST VADODARA, GUJARAT., 0 SIVAM GHOSH 5/4 BARASAT HOUSING ESTATE, PHASE‐II P O NOAPARA, 495.00 24‐PAGS(N) 743707, , 0 SWAPAN CHAKRABORTY M/S MODERN SALES AGENCY, 65A CENTRAL RD P O 495.00 -

Cpmg / Ka / Bg-Gpo/13/2003-2005

KARNATAKA ACT NO 27 OF 2005 THE KARNATAKA VALUE ADDED TAX (SECOND AMENDMENT) ACT, 2005 Arrangement of Sections Sections: 1. Short title and commencement 2. Amendment of section 4 3. Amendment of section 11 4. Amendment of section 15 5. Amendment of section 16 6. Amendment of first Schedule 7. Amendment of second Schedule 8. Amendment of third Schedule 9. Repeal and Savings STATEMENT OF OBJECTS AND REASONS To give effect to the decisions of the Empowered Committee of State Finance Ministers making modifications in the lists of commodities exempt from tax and commodities taxable at four percent and also to provide for optional payment of tax on medicines on maximum retail price basis, the Karnataka Value Added Tax Act, 2003, had to be amended for their implementation. As the Empowered Committee had also resolved that the changes in the tax rates must be given effect to from the first day of May, 2005 and as the Government of India has agreed to compensate any loss of revenue incurred by the States on introduction of VAT, only if the States implement VAT as per the design decided by the Empowered Committee, considering that the State Legislative Council was not in session, the Karnataka Value Added Tax (Amendment) Ordinance, 2005 was promulgated on seventh day of June, 2005 to bring in the above changes in the Karnataka Value Added Tax Act, 2003. Opportunity was also taken to bring in certain clarificatory amendments, to extend composition facility to sweet meat stalls and ice cream parlours on par with hoteliers and to extend input tax rebate to all goods dispatched outside the State on stock transfer. -

INDIA 6 PERMACULTURE 1 NORTHERN INDIA This Is a Non-Commercial Abstract for Educational Purpose Only

INDIA_6_PERMACULTURE 1 NORTHERN INDIA This is a non-commercial abstract for e!"cational p"r#ose onl$% Pict"res shown here' and texts use! are taken from various so"rces incl"!ing Google an! Wi)i#e!ia% 6.1 WATER 2 Trenches 3 Chec) Dam 4 Catchment / Pon! 6 Rechar+e Well 7 Tank Drinking Well 0 Hand Pump P"ri ication 9 (Kundi) (Kui) (design Anil Laul) 6.2 INRA2TRUCTURE Dr$ Stone 10 Wall Gate R ad 2he! .. 3io Fence 12 Hedge !" #ns 13 $spalier 14 %am& 6.3 SOIL 4ast Trees 1' Cover Crop 16 Com#ost 17 Pit Toilet 1( 2ealing 19 6.6 FORE2T -ood 20 4r"it Trees 21 4lower Trees 22 Others 23 Palms 24 (Ka)"na#) (*"almali) + 3anana 2' 6./ CROP No-Till 26 2ee!balls 27 ,rains 2( ,rasses 29 3hang (,asan &u Fu.u .a) 6.6 GARDEN /u#se#0 Pandal 7ines 30 4lowers 31 Herbs 32 6.8 PROCE22IN, $nerg0 - d St #age P#eser1ati n Medi)ine 6.0 ANIMAL2 Inse)ts %ees %i#ds G shala D"ng 33 639 PLAN!* 4- /4RTHER/ 2/5IA A& ut 140 plants 6# m / #t"e#n India3 Left ut a#e all poisen us plants, and (alm st) all 6# m t"e Ameri)as. -# m Wi.ipedia and Religious & Useful Plants of Nepal & India (5#3 R "it Kuma# ,a8upu#ia)3 THORN29 9abra (ma:3 1m)7 9aranda (3)7 ,"++"l (4)7 9air (')7 2hi)akai ()limbing710)7 3er (1')7 K"ai# (1')7 %abul (20)3 E2PALIER9 All t#ees, &ut esp. -

Government of India Indian Institute of Management (IIM), Kashipur IIM Kashipur Dated: 19/11/2019 To

Print Government of India Indian Institute of Management (IIM), Kashipur IIM Kashipur Dated: 19/11/2019 To Shri Shri Mantosh Kumar Dr. Shakuntala Misra National Rehabilitation University, Male Hostel, Block -1, room no. 203 Mohan Road, Lucknow 226017 Registration Number : IIMKP/R/2019/00023 Dear Sir/Madam I am to refer to your Request for Information under RTI Act 2005, received vide letter dated 09/10/2019 and to say that point wise reply is attached for perusal. In case, you want to go for an appeal in connection with the information provided, you may appeal to the Appellate Authority indicated below within thirty days from the date of receipt of this letter. Mahesh Chandra Joshi FAA & CHIEF ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICER Address: IIM KASHIPURKUNDESHWARI, KASHIPURUDHAM SINGH NAGAR, UTTARAKHAND Phone No.: 7088270882 Yours faithfully ( Ravi Gupta) CPIO & Administrative Officer Phone No.: 9759588803 Email : [email protected] / Government of India Indian Institute of Management (IIM), Kashipur IIM Kashipur Dated: 19/11/2019 To Shri NARIMETI RAKESH 3-5-139/5 HYDERGUDA, SHIVANAGAR COONY HYDERABAD 500048 Registration Number : IIMKP/R/2019/80029 Dear Sir/Madam I am to refer to your Request for Information under RTI Act 2005, received vide letter dated 28/08/2019 and to say that point wise reply is attached for perusal. In case, you want to go for an appeal in connection with the information provided, you may appeal to the Appellate Authority indicated below within thirty days from the date of receipt of this letter. Mahesh Chandra Joshi FAA & CHIEF -

Power Grid Corporation of India Limited (Cin: L40101dl1989goi038121)

POWER GRID CORPORATION OF INDIA LIMITED (CIN: L40101DL1989GOI038121) LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS WHOSE SHARES ARE TRANSFERRED TO IEPF AUTHORITY Nominal Investor Middle Investor Last No. of Value of Actual date of Sl.No. Investor First Name Name Name Address State Pin Folio No. DP id-Client id shares shares transfer to IEPF 1 BHANU PRAKASH AGRAWAL D-64/132-2 MADHOPUR SIGRA VARANASI UTTARUTTAR PRADESH PRADESH 221010 C12010600-12010600-00360049 583 5830.00 23-APR-2018 2 MAHESHKUMAR LALBHAI PATEL BHARAT NAGAR AT-HANSOT BHARUCH GUJARATGUJARAT 393030 C12010600-12010600-00658579 65 650.00 23-APR-2018 3 BAVIRISETTY RAJENDAR NO. 4-5-53 MAHAMBUBABAD WARANGAL ANDHRAANDHRA PRADESH PRADESH 506101 C12010600-12010600-00726110 3 30.00 23-APR-2018 4 SHAM ACHUTRAO JADHAV SUVARNAKAR NAGAR JALNA MAHARASHTRAMAHARASHTRA 431203 C12010600-12010600-00758263 100 1000.00 23-APR-2018 5 B S HIRERADDI H NO 413 TQ - RAMDURG DIST- BELGAUM AVARADIKARNATAKA KARNATAKA 591127 C12010600-12010600-00857218 9 90.00 23-APR-2018 6 CHANDRA KANTA BORA P.G.C.I POWER GRID CORPORATION OF INDIA LTD.ASSAM 400 KV MISA S/S VELUGURI,782427 KATHIATOLI NAGAONC12010600-12010600-00875803 ASSAM 314 3140.00 23-APR-2018 7 GOYAL DIMPLE H.NO.16-04-1122 SHIVNAGAR OPPOSITE SATYAANDHRA SAI BHAJAN PRADESH MANDIR WARANGAL506002 ANDHRA PRADESHC12010600-12010600-00899757 100 1000.00 23-APR-2018 8 DAMODAR SAMAL AT- JAGANNATHPUR (NEAR SALES TAX COLONY)ORISSA BHADRAK ODISHA 756100 C12010600-12010600-00975411 65 650.00 23-APR-2018 9 BAJRANG LAL AGRAWAL MAIN ROAD KAWARDHA CHHATTISGARH CHHATTISGARH 491995 C12010600-12010600-01025817 -

CSC E Governance Services Ltd

CSC e_Governance Services Ltd. Sr.No Agent Name Agent Address Dist name State name Pincode 1 Aayuesh Goel Kalsi Road Dakpathar Vikasnagar Dehradun Dehradun Uttarakhand 248125 Gandhi Bomma Center Road, Beside Vro Office, Alamuru, East 2 Achanta Srinivasarao East Godavari Andhra Pradesh 533233 Godavari, Ap 3 Ajay Joshi Pitgara, Badnawar, Dist. Dhar Dhar Madhya Pradesh 454660 4 Ajay Kumar Noukri Point, Rani Bajaar,Nohar Hanumangarh Rajasthan 335523 5 Akhilesh Thakur Court Road Dhar Dhar Madhya Pradesh 454446 4-125, Gandhi Center, Paritala, Kanchikacherla, Krishna, Andhra 6 Akula Narasimhaswamy Krishna Andhra Pradesh 521180 Pradesh 7 Anil Kumar Manjeri Csc Center,Poonthottathil Tower Nilambur Road Manjeri Malappuram Kerala 676121 8 Anil Namta Yashmehul Studio,Bagbera Colony J.P. Road East Singhbhum Jharkhand 831002 9 Ankit Saini Sarthak Computer Education Holi Tiba Tijara Alwar Rajasthan 301411 10 Arvind Madan Teli Near Bus Stand, Jalgaon Road, Jamner, Jalgaon Jalgaon Maharashtra 424206 11 Aziz Gohar Khan Tareen Vill Thapal, Najibabad Distt Bijnor Up Bijnor Uttar Pradesh 246763 12 Balwinder Singh Near Sub Tehsil, Alal Road Sherpur Sangrur Punjab 148025 13 Basavaraj Hiremath Maheshwar Digital,509, Main Road Pathade Galli Akkol-591211 Belgaum Karnataka 591211 14 Bhera Ram Prime Computers Opp. Rajasthan Marudhar Bank Bilara Jodhpur Jodhpur Rajasthan 342602 15 Chekka Suresh Kumar 7-135 Main Road Opp Sbi Rayavaram, East Godavari, Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Andhra Pradesh 533346 16 Chitikesu Harisuman H No 8-1-70 ,Opp.Mamatha Hospital , Jammikunta -

Agent List - East Zone

Agent List - East Zone OFFICE_ AGENT_COD AGENT_NAME ADDRESS PINCODE CONTACT_NO PAN_NO DATE_OF_ENROLLMENT CODE E 1 NO.TOWN,PURANI MASJIDSUBHASH MARG,BARA 210405 AGD0116231 AAFTAB ALAM 825301 9308975372 AKQPA9346P 22/07/2014 BAZAR 260400 AGD0050974 ABANISH PANDA BHABANI FIELDDHANUPALISAMBALPUR 768005 9437175339 AHCPP5325L 08/01/2002 130200 AGI0027715 ABDUL MUEZE CHOWDHURY ARUN PRAKASH MANSION 781005 9435041413 AEHPC0112J 25/06/2011 270500 AGD0081237 ABDUL GANI ISMAIL 34, RDA COLONY, SANJAY NAGAR, RAIPUR 492001 7587050021 AJJPG6250E 27/04/2012 130604 AGD0057842 ABDUL HALIM VILL.JOYPUR,P.O.JOYPUR BAZAR,P.S.B 783101 9401159982 ABUPH7432A 01/01/2010 031602 AGD0005761 ABDUL HAMID MONDAL SHIKRA , SHIKRA P.O.-PADDAMALA, DI 741101 9732546545 AJHPM7840E 28/03/2002 131001 AGD0120342 ABDUL HANNAN MAIRABARI, NAGAON 782125 9854783857 AFHPH9273G 30/01/2012 VILL:DINKAR, P.O: KAMALPUR, VIA: BAIHATA CHARIALI, 130184 AGD0117607 ABDUL JALIL 600014 9854509487 AFOPJ2805H 23/09/2013 P.S: KAMALPUR,DIST: KAMRUP ,ASSAM. 130602 AGD0030284 ABDUL KADDUS ALI AHMED VILL.:SATRAKANARA 6 NO.SIT,PO.:SAT 781315 9954255369 AKZPA0506E 14/09/2007 210604 AGD0101517 ABDUL LATIF DR. B.N COMPLEX 834002 9955120720 ABEPL9090Q 16/01/2011 031402 AGD0113910 ABDUL MOID BABUYA S/O- ABANI GHOSH 742202 9153084278 AGMPB8612P 14/05/2012 260300 AGD0078062 ABDUL RAHMAN KHAN B-V-88,KRISHAN NAGAR, KAPURTHALA 144001 9778860153 AGWPK7612E 22/10/2013 035101 AGD0006006 ABDUL SALEK ALI SIBESWAR,GOBRA CHHRA,DINHATA,COOCH 736101 9547393135 AGIPA6197J 26/12/2012 130604 AGD0086068 ABDUL WAHHAB KHANDAKAR VILL.KALLYANPUR,P.O.BAGUAN 783121 9954321568 BAGPK0467E 12/08/2011 130681 AGD0102894 ABDULKHALEQUE SAGUNMARIPT.-II,P.O.BILASIPARA,DT.DHUBRI 783348 9957084509 AWMPK1267F 11/09/2007 VILL.ANANDANAGAR,W/NO.1,P.O.BILASIPARA,DIST.DHUB 130681 AGD0102652 ABDULLAALMAMUN 783348 9954648114 AYRPM1481A 29/09/2007 RI,ASSAM-783348 S/O.LT.MAHEJALI.AHMED,MENDHIRJHAR,WARDNO.8,P.O. -

Indigenous Uses of Wild and Tended Plant Biodiversity Maintain Ecosystem Services in Agricultural Landscapes of the Terai Plains of Nepal

Indigenous uses of wild and tended plant biodiversity maintain ecosystem services in agricultural landscapes of the Terai Plains of Nepal Jessica P. R. Thorn ( [email protected] ) University of York https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2108-2554 Thomas F. Thornton University of Oxford School of Geography and Environment Ariella Helfgott University of Oxford Katherine J. Willis University of Oxford Department of Zoology, University of Bergen Department of Biology, Kew Royal Botanical Gardens Research Keywords: agrobiodiversity conservation; ethnopharmacology; ethnobotany; ethnoecology; ethnomedicine; food security; indigenous knowledge; medicinal plants; traditional ecological knowledge Posted Date: March 26th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.18028/v2 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published at Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine on June 8th, 2020. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-020-00382-4. Page 1/32 Abstract Background Despite a rapidly accumulating evidence base quantifying ecosystem services, the role of biodiversity in the maintenance of ecosystem services in shared human-nature environments is still understudied, as is how indigenous and agriculturally dependent communities perceive, use and manage biodiversity. The present study aims to document traditional ethnobotanical knowledge of the ecosystem service benets derived from wild and tended plants in rice-cultivated agroecosystems, compare this to botanical surveys, and analyse the extent to which ecosystem services contribute social-ecological resilience in the Terai Plains of Nepal. Method Sampling was carried out in four landscapes, 22 Village District Committees and 40 wards in the monsoon season.