Hitting Streaks Don't Obey Your Rules

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TODAY's HEADLINES AGAINST the OPPOSITION Home

ST. PAUL SAINTS (6-9) vs INDIANAPOLIS INDIANS (PIT) (9-5) LHP CHARLIE BARNES (1-0, 4.00) vs RHP JAMES MARVEL (0-0, 3.48) Friday, May 21st, 2021 - 7:05 pm (CT) - St. Paul, MN - CHS FIeld Game #16 - Home Game #10 TV: FOX9+/MiLB.TV RADIO: KFAN Plus 2021 At A Glance TODAY'S HEADLINES AGAINST THE OPPOSITION Home .....................................................4-5 That Was Last Night - The Saints got a walk-off win of their resumed SAINTS VS INDIANAPOLIS Road ......................................................2-4 game from Wednesday night, with Jimmy Kerrigan and the bottom of the Saints order manufacturing the winning run. The second game did .235------------- BA -------------.301 vs. LHP .............................................1-0 not go as well for St. Paul, where they dropped 7-3. Alex Kirilloff has vs. RHP ............................................5-9 homered in both games of his rehab assignment with the Saints. .333-------- BA W/2O ----------.300 Current Streak ......................................L1 .125 ------- BA W/ RISP------- .524 Most Games > .500 ..........................0 Today’s Game - The Saints aim to preserve a chance at a series win 9 ----------------RUNS ------------- 16 tonight against Indianapolis, after dropping two of the first three games. 2 ----------------- HR ---------------- 0 Most Games < .500 ..........................3 Charlie Barnes makes his third start of the year, and the Saints have yet 2 ------------- STEALS ------------- 0 Overall Series ..................................1-0-1 to lose a game he’s started. 5.00 ------------- ERA ----------- 3.04 Home Series ...............................0-0-1 28 ----------------- K's -------------- 32 Keeping it in the Park - Despite a team ERA of 4.66, the Saints have Away Series ................................0-1-0 not been damaged by round-trippers. -

Atlanta Braves (45-52) Vs

Atlanta Braves (45-52) vs. St. Louis Cardinals (63-34) Game No. 98 July 26, 2015 Busch Stadium St. Louis, Mo. RHP Matt Wisler (4-1, 3.60) vs. RHP Michael Wacha (11-3, 3.20) TODAY’S GAME: The Braves and St. Louis Cardinals play the fi nale of a three-game set and the third of six meetings between the two clubs this season...The Braves and Cardinals wrap up the 2015 campaign with a three-game Braves vs. Cardinals set at Atlanta (Oct. 2-4)...Atlanta trails the Cardinals in the all-time series 890-1037-18, including a 240-273-1 mark 2014 2015 All-Time during the Atlanta era (since 1966)...The Braves also trail 12-19 at Busch Stadium...ROAD TRIPPIN: Last night Overall (since 1900) 2-4 0-1 890-1037-18 Atlanta Era (since ‘66) --- --- 240-273-1 the Braves opened a 10-game road trip to St. Louis (0-2), Baltimore (July 27-29) and Philadelphia (July 30-August 2). at Atlanta 1-2 --- 129-128 SMOLTZ TO BE INDUCTED TODAY: Former Braves pitcher John Smoltz will be inducted into the Na- at Turner Field --- --- 40-24 tional Baseball Hall of Fame today in Cooperstown, NY...Acquired from Detroit by GM Bobby Cox in 1987, Smoltz at St. Louis 1-2 0-1 419-552-11 fashioned his Hall of Fame career by excelling as both a starter and reliever over the span of two decades from 1988 to at Busch Stad. (since ‘06) --- --- 12-19 2008...He is the only pitcher in major league history with 200 or more wins and 150-plus saves...In 14 full seasons as a starter, Smoltz won 14 or more games 10 times...Twice, he led the NL or shared the lead in wins (1996 and 2006), in- nings -

Sabermetrics: the Past, the Present, and the Future

Sabermetrics: The Past, the Present, and the Future Jim Albert February 12, 2010 Abstract This article provides an overview of sabermetrics, the science of learn- ing about baseball through objective evidence. Statistics and baseball have always had a strong kinship, as many famous players are known by their famous statistical accomplishments such as Joe Dimaggio’s 56-game hitting streak and Ted Williams’ .406 batting average in the 1941 baseball season. We give an overview of how one measures performance in batting, pitching, and fielding. In baseball, the traditional measures are batting av- erage, slugging percentage, and on-base percentage, but modern measures such as OPS (on-base percentage plus slugging percentage) are better in predicting the number of runs a team will score in a game. Pitching is a harder aspect of performance to measure, since traditional measures such as winning percentage and earned run average are confounded by the abilities of the pitcher teammates. Modern measures of pitching such as DIPS (defense independent pitching statistics) are helpful in isolating the contributions of a pitcher that do not involve his teammates. It is also challenging to measure the quality of a player’s fielding ability, since the standard measure of fielding, the fielding percentage, is not helpful in understanding the range of a player in moving towards a batted ball. New measures of fielding have been developed that are useful in measuring a player’s fielding range. Major League Baseball is measuring the game in new ways, and sabermetrics is using this new data to find better mea- sures of player performance. -

2021 Sun Devil Baseball GAME NOTES - OREGON

2021 Sun Devil Baseball GAME NOTES - OREGON GAMES 15-17 March 19-21 #23 ARIZONA STATE 4p.m./2 p.m./12 p.m. AZT #19 Oregon 11-3 (0-0 Pac-12) PK Park 8-3/0-0 Pac-12 Eugene, Ore. @ASU_Baseball Watch: Pac-12 Live Stream @OregonBaseball @TheSunDevils Radio: N/A @GoDucks Five -Time NCAA Champions (1965, 1967, 1969, 1977, 1981) | 22 College World Series Appearances | 21 Conference Championships | 128 All-Americans | 14 National Players of the Year | 12 College Baseball Hall of Famers MEDIA RELATIONS CONTACT ASU_BASEBALL SUN DEVIL BASEBALL ASU_BASEBALL Jeremy Hawkes 2021 @ASU_BASEBALL Schedule [email protected] | C: 520-403-0121 | O: 480-965-9544 Date Opponent Time/Score 19-Feb Sacramento State^ L, 2-4 20-Feb Sacramento State^ W, 2-1 #10THINGS (Twitter-Friendly Notes) #BYTHENUMBERS 21-Feb Sacramento State^ W, 3-1 ASU has held its opponents to 5 runs or fewer in 26-Feb Hawaii L, 2-3 27-Feb Hawaii W, 6-5 1. Dating back to last year, ASU has held oppo- 28 of the 31 games since Jason Kelly has come on as 27-Feb Hawaii W, 9-6 nents to five runs or fewer in 28 of the 31 games the pitching coach. For perspective, ASU gave up six or 2-Mar Nevada W, 13-4 5-Mar Utah W, 4-3 since Jason Kelly’s arrival. more runs in 25 of its 57 games in 2019. Even despite a 6-Mar Utah W, 4-1 tough 10-runs allowed against UNLV, ASU is 20th in the 7-Mar Utah W, 5-0 2. -

Baseball Milestones: Barry, Alex, and Tom

University of Central Florida STARS On Sport and Society Public History 8-17-2007 Baseball milestones: Barry, Alex, and Tom Richard C. Crepeau University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Cultural History Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Other History Commons, Sports Management Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Public History at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in On Sport and Society by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Crepeau, Richard C., "Baseball milestones: Barry, Alex, and Tom" (2007). On Sport and Society. 751. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety/751 SPORT AND SOCIETY FOR H-ARETE Baseball milestones: Barry, Alex, and Tom AUGUST 17, 2007 Over two weeks ago before taking a short vacation to escape the heat and humidity of Florida, I saw the Barry Bonds home run that tied Henry Aaron. That same day Alex Rodriguez hit his 500th home run and all those fans with steroid anxiety suddenly discovered a new hero. Even before Bonds had officially passed Aaron, A-Rod became the Great Clean Hope who would surpass "Mr. Bonds," as Bud Selig so warmly called him, and bring the home run crown back to the kind of people who hold it by divine fiat. The next day Tom Glavine won his 300th game, becoming only the fifth left-hander and the twenty-third member of that exclusive club. -

Edia Informationmedia Relations Department 198 Union Avenue | Memphis, Tennessee 38103 | Phone: 901.722.0293 | | @Memphisredbirds

edia InformationMedia Relations Department 198 Union Avenue | Memphis, Tennessee 38103 | Phone: 901.722.0293 | www.memphisredbirds.com | @memphisredbirds MEMPHIS REDBIRDS (74-48) VS NEW ORLEANS BABY CAKES (60-61) Thursday, August 16 • 7:05 p.m. (CT) • AutoZone Park (10,000) • Memphis, Tennessee Game #123 • Home Game #63 (35-27) LHP Tyler Lyons (0-0, 0.00 ERA) vs. RHP Jeff Brigham (4-0, 2.62 ERA) THE GAME 2.62 ERA in 34.1 innings of work. Brigham has thrown at REDBIRDS VS. BABY CAKES TODAY’S GAME: The Memphis Redbirds and New Orleans least five innings in all but one of his starts. He has yet to 2018: 5-7 Baby Cakes will play the finale of a four-game set tonight allow more than two earned runs in an appearance, and has at Memphis: 3-4 at 7:05 p.m. in Memphis. It is the third of four series the yet to strike out fewer than five batters in a game. at New Orleans: 2-3 two teams will play against one another this season, and All-Time: 163-169 the last they will play at AutoZone Park. The fourth and final HISTORY WITH NEW ORLEANS: Memphis and New All-Time at Home: 94-73 series will take place next week in New Orleans. New Orleans Orleans have played every season dating back to 1998 All-Time at Road: 69-96 has won the first three games of the series, giving them the when the Redbirds joined the PCL. In that span, Memphis 7-5 lead in the season series. -

Name of the Game: Do Statistics Confirm the Labels of Professional Baseball Eras?

NAME OF THE GAME: DO STATISTICS CONFIRM THE LABELS OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL ERAS? by Mitchell T. Woltring A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Leisure and Sport Management Middle Tennessee State University May 2013 Thesis Committee: Dr. Colby Jubenville Dr. Steven Estes ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would not be where I am if not for support I have received from many important people. First and foremost, I would like thank my wife, Sarah Woltring, for believing in me and supporting me in an incalculable manner. I would like to thank my parents, Tom and Julie Woltring, for always supporting and encouraging me to make myself a better person. I would be remiss to not personally thank Dr. Colby Jubenville and the entire Department at Middle Tennessee State University. Without Dr. Jubenville convincing me that MTSU was the place where I needed to come in order to thrive, I would not be in the position I am now. Furthermore, thank you to Dr. Elroy Sullivan for helping me run and understand the statistical analyses. Without your help I would not have been able to undertake the study at hand. Last, but certainly not least, thank you to all my family and friends, which are far too many to name. You have all helped shape me into the person I am and have played an integral role in my life. ii ABSTRACT A game defined and measured by hitting and pitching performances, baseball exists as the most statistical of all sports (Albert, 2003, p. -

2013 Baseball Hall of Fame Natalie Weinberg University of Pennsylvania [email protected]

COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE Winter 2014 MICROECONOMICS 2013 Baseball Hall of Fame Natalie Weinberg University of Pennsylvania [email protected] Abstract The purpose of this paper is to outline potential reasons why the 2013 election vote into the Baseball Hall of Game failed to elect a new player. The paper compares various voting rules, and analyzes specific statistics of players. 6 COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE Winter 2014 MICROECONOMICS When a player is elected into nually (baseballhall.org). sdfsdf Each voter from the BBWAA the Baseball Hall of Fame, he The eligible candidate pool submits his or her top 10 pre- enters the club of the “immor- for the players ballot each year ferred candidates that he or she tals” (New York Times). The consists of all players who were feels is worthy to be inducted Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, part of Major League Baseball into the Hall from the list on New York, is a museum that (the MLB) for at least 10 con- the ballot (bbwaa.com). The honors and preserves the lega- secutive years and have been listed order is not relevant to 1 cy of outstanding baseball play- retired for at least five . Another the voting; each player in the ers throughout the decades. A committee narrows down this group of 10 is treated equally in player receives a great honor by pool to 200 players, and then the the count. In addition, a voter being voted in, and his career is 60-person BBWAA screening is only restricted to nominating stamped with a seal of approv- committee compiles the top 25 10 candidates, but he or she can al by the fans of the game. -

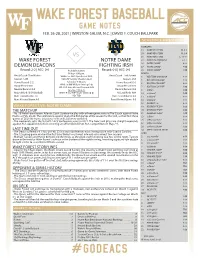

WF BASE Notes -ND.Indd

FEB. 26-28, 2021 | WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. | DAVID F. COUCH BALLPARK SCHEDULE & RESULTS FEBRUARY 19 NORTHEASTERN W, 8-6 20 NORTHEASTERN W, 9-0 VS 21 NORTHEASTERN L, 14-11 WAKE FOREST NOTRE DAME 23 COASTAL CAROLINA L, 4-1 26 NOTRE DAME* 4:00 DEMON DEACONS FIGHTING IRSH 27 NOTRE DAME* 4:00 Record: 2-2 | ACC: 0-0 Probable Starters Record: 0-0 | ACC: 0-0 28 NOTRE DAME* 1:00 Friday- 4:00 p.m. MARCH Head Coach: Tom Walter WAKE: So. RHP Ryan Cusick (0-0) Head Coach : Link Jarrett 3 WESTERN CAROLINA 6:00 Season: 12th ND: LHP Tommy Sheehan (0-0) Season: 2nd 5 BOSTON COLLEGE* 4:00 Saturday- 4:00 p.m. Home Record: 2-2 Home Record: 0-0 6 BOSTON COLLEGE* 4:00 Away Record: 0-0 WAKE: Jr. RHP William Fleming (1-0) Away Record: 0-0 ND: LHP John Michael Betrand (0-0) 7 BOSTON COLLEGE* 1:00 Neutral Record: 0-0 Sunday- 1:00 p.m. Neutral Record: 0-0 9 at Elon 4:00 National Rank: 16 (D1 Baseball) WAKE: R-So. RHP Shane Smith (0-0) National Rank: N/A 12 at Miami* 7:00 Runs Scored/Game: 7.3 ND: TBD Runs Scored/Game: 0.0 13 at Miami* 6:00 Runs Allowed/Game: 6.0 Runs Allowed/Game: 0.0 14 at Miami* 1:00 16 CHARLOTTE 6:00 WAKE FOREST VS. NOTRE DAME 19 GEORGIA TECH* 6:00 THE MATCHUP 20 GEORGIA TECH* 4:00 • No. 16 Wake Forest opens Atlantic Coast Conference play with a three-game series at The Couch against Notre 21 GEORGIA TECH* 1:00 Dame on Feb. -

Lombardozzi Field Staff Infield Ht 5'11" Wt 193 | Bats Switch Throws Right Mlb Service 2 Years, 84 Days | Mlb Debut September 6, 2011 Vs

FRONT OFFICE STEVE LOMBARDOZZI FIELD STAFF INFIELD HT 5'11" WT 193 | BATS SWITCH THROWS RIGHT MLB SERVICE 2 YEARS, 84 DAYS | MLB DEBUT SEPTEMBER 6, 2011 VS. LOS ANGELES-NL (W/WSH) | BIRTHPLACE EDINA, MN BORN SEPTEMBER 20, 1988 | OPENING DAY AGE 28 | CONTRACT STATUS SIGNED THROUGH 2017 PLAYERS ACQUIRED SIGNED AS MINOR LEAGUE FREE AGENT ON FEBRUARY 28, 2017 2016 SUMMARY CAREER BESTS • Spent entire season with Triple-A Syracuse in Washington’s system, batting .253 (57x225) in 62 games. HITS .............................................. 4 (3x) — LAST, 8/15/12 at SF • Best month was July, when he batted .304 (24x79) in 22 RUNS ........................................................... 4 — 8/10/12 at ARI games, with 12 runs scored, two doubles, and a triple. 2016 IN REVIEW 2016 • Had four consecutive multi-hit games from July 7-10, going HOME RUNS ............................. 1 (5x) — LAST, 8/30/13 vs. NYM 9x17 (.529); also had longest hitting streak of the season that RBI ................................................................ 3 — 7/26/12 at MIL month, a seven-game run from July 21-30 (.435/10x23). SB ............................................... 1 (10x) — LAST, 4/16/14 vs. TB MAJOR LEAGUE CAREER HIGHLIGHTS HITTING STREAK ................................. 13 — 6/29/12 to 7/20/12 • Began 2015 with Triple-A Indianapolis before being recalled GRAND SLAMS ........................................................................ — CLUB HISTORY CLUB by the Pirates on May 6; went 0x4 over six games before being CAREER PINCH-HIT HR .............................. 1 — 8/30/13 vs. NYM optioned to Indianapolis on May 16. CAREER GAME-ENDING HR .................................................... — • Recalled by Pittsburgh on June 28, going 0x6 in six games before being designated for assignment on July 23 and outrighted to Indianapolis on July 27. -

Boston College at Duke Dates: Feb

BostonBaseball College 2021 Schedule Boston College at Duke Dates: Feb. 26-28 Times: 3 p.m. • 3 p.m. • 1 p.m. Location: Durham, N.C. Stadium: Durham Bulls Athletic Park Date Opponent Time/Result Watch: ACC Network, ACCNX Listen: n/a Twitter: @BCBirdball Live Stats: BCEagles.com/BSBstats Feb. 19 at Charleston Southern W, 12-4 Feb. 20 at Charleston Southern W, 12-1 Eagles Blue Devils Feb. 21 at Charleston Southern Noon Overall: 3-0 Overall: 2-1 Feb. 26 at #11Duke* [ACCN] 3 p.m. ACC: 0-0 ACC: 0-0 N BA D1B/N CBN Feb. 27 at #11Duke* [ACCNX] 3 p.m. 4-6 Game Rank: RV Rank: 11 /25 /28 Feb. 28 at #11Duke* [ACCNX] 1 p.m. Coach: Mike Gambino Coach: Chris Pollard March 5 at Wake Forest* 4 p.m. Career Record: 217-284/11 Career Record: 632-496-3/22 March 6 at Wake Forest* 4 p.m. Friday (ACC Network) Saturday (ACCNX) Sunday (ACCNX) March 7 at Wake Forest* 1 p.m. Play-by-play ................. Mike Monaco Play-by-play ................Chris Edwards Play-by-play ................Chris Edwards March 9 Holy Cross 4 p.m. TV Color analyst .........Adam Greenberg March 12 at Louisville* 6 p.m. March 13 at Louisville* 1 p.m. First Pitch... All-Time vs. Duke... March 14, at Louisville* 1 p.m. The Boston College baseball team begins ACC play this Boston College is 19-14 all-time against Duke with all 33 March 17 Holy Cross 4 p.m. weekend vs. No. 11 Duke at Durham Bulls Athletic Park. -

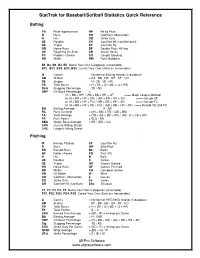

Stattrak for Baseball/Softball Statistics Quick Reference

StatTrak for Baseball/Softball Statistics Quick Reference Batting PA Plate Appearances HP Hit by Pitch R Runs CO Catcher's Obstruction H Hits SO Strike Outs 2B Doubles SH Sacrifice Hit (sacrifice bunt) 3B Triples SF Sacrifice Fly HR Home Runs DP Double Plays Hit Into OE Reaching On-Error SB Stolen Bases FC Fielder’s Choice CS Caught Stealing BB Walks RBI Runs Batted In B1, B2, B3, B4, B5 Name Your Own Categories (renamable) BS1, BS2, BS3, BS4, BS5 Create Your Own Statistics (renamable) G Games = Number of Batting records in database AB At Bats = PA - BB - HP - SH - SF - CO 1B Singles = H - 2B - 3B - HR TB Total Bases = H + 2B + (2 x 3B) + (3 x HR) SLG Slugging Percentage = TB / AB OBP On-Base Percentage = (H + BB + HP) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Major League Method or (H + BB + HP + OE) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Include OE or (H + BB + HP + FC) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Include FC or (H + BB + HP + OE + FC) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Include OE and FC BA Batting Average = H / AB RC Runs Created = ((H + BB) x TB) / (AB + BB) TA Total Average = (TB + SB + BB + HP) / (AB - H + CS + DP) PP Pure Power = SLG - BA SBA Stolen Base Average = SB / (SB + CS) CHS Current Hitting Streak LHS Longest Hitting Streak Pitching IP Innings Pitched SF Sacrifice Fly R Runs WP Wild Pitch ER Earned-Runs Bk Balks BF Batters Faced PO Pick Offs H Hits B Balls 2B Doubles S Strikes 3B Triples GS Games Started HR Home Runs GF Games Finished BB Walks CG Complete Games HB Hit Batter W Wins CO Catcher's Obstruction L Losses SO Strike Outs Sv Saves SH Sacrifice Hit