Marc Bolan, David Bowie, and the Counter-Hegemonic Persona: 'Authenticity', Ephemeral Identities, and the 'Fantastical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Rock Music: 1970-1975

The History of Rock Music: 1970-1975 History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page Inquire about purchasing the book (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Decadence 1969-76 (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") As usual, the "dark age" of the early 1970s, mainly characterized by a general re-alignment to the diktat of mainstream pop music, was breeding the symptoms of a new musical revolution. In 1971 Johnny Thunders formed the New York Dolls, a band of transvestites, and John Cale (of the Velvet Underground's fame) recorded Jonathan Richman's Modern Lovers, while Alice Cooper went on stage with his "horror shock" show. In London, Malcom McLaren opened a boutique that became a center for the non-conformist youth. The following year, 1972, was the year of David Bowie's glam-rock, but, more importantly, Tom Verlaine and Richard Hell formed the Neon Boys, while Big Star coined power-pop. Finally, unbeknownst to the masses, in august 1974 a new band debuted at the CBGB's in New York: the Ramones. The future was brewing, no matter how flat and bland the present looked. Decadence-rock 1969-75 TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. Rock'n'roll had always had an element of decadence, amorality and obscenity. In the 1950s it caused its collapse and quasi-extinction. -

Melodrama, Sickness, and Paranoia: Todd Haynes and the Womanâ•Žs

University of Texas Rio Grande Valley ScholarWorks @ UTRGV Literatures and Cultural Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations College of Liberal Arts Winter 2016 Melodrama, Sickness, and Paranoia: Todd Haynes and the Woman’s Film Linda Belau The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Ed Cameron The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utrgv.edu/lcs_fac Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Belau, L., & Cameron, E. (2016). Melodrama, Sickness, and Paranoia: Todd Haynes and the Woman’s Film. Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal 46(2), 35-45. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/643290. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts at ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. It has been accepted for inclusion in Literatures and Cultural Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Film & History 46.2 (Winter 2016) MELODRAMA, SICKNESS, AND PARANOIA: has so much appeal precisely for its liberation from yesterday’s film culture? TODD HAYNES AND THE WOMAN’S FILM According to Mary Ann Doane, the classical woman’s film is beset culturally by Linda Belau the problem of a woman’s desire (a subject University of Texas – Pan American famously explored by writers like Simone de Beauvoir, Julia Kristeva, Helene Cixous, and Ed Cameron Laura Mulvey). What can a woman want? University of Texas – Pan American Doane explains that filmic conventions of the period, not least the Hays Code restrictions, prevented “such an exploration,” leaving repressed material to ilmmaker Todd Haynes has claimed emerge only indirectly, in “stress points” that his films do not create cultural and “perturbations” within the film’s mise artifacts so much as appropriate and F en scène (Doane 1987, 13). -

Joan Jett and Hal Willner's Friends Talk About His 'Masterpiece,' the T. Rex Tribute Album 'Angelheaded Hipster'

Login HOME > MUSIC > NEWS Sep 4, 2020 11:00am PT Joan Jett and Hal Willner’s Friends Talk About His ‘Masterpiece,’ the T. Rex Tribute Album ‘Angelheaded Hipster’ B y R o y T r a k i n 0 Luiz C. Ribeiro When veteran music producer Hal Willner passed away due to complications believed to be associated with Covid-19 on April 7, a day after his 64th birthday, the music community in New York and beyond was devastated. Willner had been the sketch music producer for “Saturday Night Live” for decades — the show paid homage with a moving four-minute video — and he’d produced albums for Lou Reed, Marianne Faithfull, Lucinda Williams, Laurie Anderson and many more. But his gifts as a producer are perhaps best evidenced in the series of mind-blowing tribute albums he oversaw (although, as we see below, he hated that term), which found artists ranging from Tom Waits — who wrote a heartfelt tribute to Willner — and Ringo Starr to Keith Richards and Wynton Marsalis paying musical homage to Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk, Kurt Weill and even music from Disney lms. ADVERTISEMENT SPONSORED BY THE NEW YORK TIMES TShE Ee M JO RoEy Of Tofu Related Stories VIP Taking the Temperature of Top Media/Tech Companies, Aug. 17-21 ‘Mom’ Star Anna Faris Exits CBS Series Ahead of Season 8 His nal project turned out to be just such an album: a collection of Marc Bolan/ T. Rex covers called “Angelheaded Hipster,” out today (Sept. 4) on BMG, that he’d working on since 2016. -

Dec. 22, 2015 Snd. Tech. Album Arch

SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) Affinity-Affinity S=Trident Studio SOHO, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R=1970 (Vertigo) E=Frank Owen, Robin Geoffrey Cable P=John Anthony SOURCE=Ken Scott, Discogs, Original Album Liner Notes Albion Country Band-Battle of The Field S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Island Studio, St. Peter’s Square, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=1973 (Carthage) E=John Wood P=John Wood SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Albion Dance Band-The Prospect Before Us S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (PARTIALLY TRACKED. MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Olympic Studio #1 Studio, Barnes, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=Mar.1976 Rel. (Harvest) @ Sound Techniques, Olympic: Tracks 2,5,8,9 and 14 E= Victor Gamm !1 SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) P=Ashley Hutchings and Simon Nicol SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Alice Cooper-Muscle of Love S=Sunset Sound Recorders Hollywood, CA. Studio #2. (TRACKED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Record Plant, NYC, A&R Studio NY (OVERDUBS AND MIX) R=1973 (Warner Bros) E=Jack Douglas P=Jack Douglas and Jack Richardson SOURCE: Original Album liner notes, Discogs Alquin-The Mountain Queen S= De Lane Lea Studio Wembley, London (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R= 1973 (Polydor) E= Dick Plant P= Derek Lawrence SOURCE: Original Album Liner Notes, Discogs Al Stewart-Zero She Flies S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. -

The Political Agenda of Todd Haynes's Far from Heaven Niall Richardson, University of Sunderland, UK

Poison in the Sirkian System: The Political Agenda of Todd Haynes's Far From Heaven Niall Richardson, University of Sunderland, UK Certainly Haynes's work does qualify as queer, but in the traditional sense of the word: unusual, strange, disturbing. (Wyatt, 2000: 175) Haynes "queers" heterosexual, mainstream narrative cinema by making whatever might be familiar or normal about it strange, and in the process hypothesising alternatives that disrupt its integrity and ideological cohesiveness. (DeAngelis, 2004: 41) Todd Haynes is one of the most controversial directors of contemporary cinema. From his student film Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (1987), to his most controversial, Poison (1991), Haynes has continually challenged spectators' expectations by making the familiar appear unfamiliar and evoking a sense of the unusual, strange, or "queer" within everyday lives. Committed to an agenda of political filmmaking, Haynes's films not only subvert Hollywood's storytelling conventions and assail the spectator with challenging images (especially Poison) but also ask the spectator to acknowledge the alienation of minority groups from mainstream society. It would, therefore, seem odd that Haynes should have recently directed Far From Heaven (2002), a homage to the melodramas of the 1950s. Unlike Haynes's other films -- Superstar, Poison, Dottie Gets Spanked (1993), Safe (1995) and Velvet Goldmine (1998) -- Far From Heaven is Haynes's first "commercial" success, popular with both mainstream audiences and critics. This paper will argue that Far From Heaven is more than simply an affectionate pastiche of Douglas Sirk's classic melodrama All That Heaven Allows (1955). Instead, Far From Heaven combines the social critique of the "Sirkian System" with the political agenda found in Poison. -

Taking Note Cover Star

WHERE IS THE LOVE? The Story behind Japan’s Frozen Population Growth TAKING NOTE Global Perspectives and New Designs in Education COVER STAR Songstress May J Breaks Through with “Let It Go” ALSO: A Chocolate Movement Comes to Tokyo, Valentine’s Gift Guide, Art around Town, Agenda, Movies,www.tokyoweekender.com and more... FEBRUARY 2015 Your Move. Our World. C M Y CM MY CY Full Relocation CMY K Services anywhere in the world. Asian Tigers Mobility provides a comprehensive end-to-end mobility service tailored to your needs. Move Management – office, households, Tenancy Management pets, vehicles Family programs Orientation and Cross-cultural programs Departure services Visa and Immigration Storage services Temporary accommodation Home and School search Asian Tigers goes to great lengths to ensure the highest quality service. To us, every move is unique. Please visit www.asiantigers-japan.com or contact us at [email protected] Customer Hotline: 03-6402-2371 FEBRUARY 2015 www.tokyoweekender.com Your Move. Our World. FEBRUARY 2015 CONTENTS 10 C MAY J. M How letting go and learning to love the Y cover song rekindled a music career CM MY CY Full Relocation 7 14 18 CMY K Services anywhere in the world. Asian Tigers Mobility provides a comprehensive end-to-end mobility service tailored to your needs. Move Management – office, households, Tenancy Management LEXUS TEST DRIVE TOKYOFIT BEAN-TO-BAR CHOCOLATE pets, vehicles Family programs Pernod Ricard Japan CEO Tim Paech takes Getting in touch with your inner child— Bringing a chocolate revolution -

Internalized Homophobia of the Queer Cinema Movement

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2010 If I Could Choose: Internalized Homophobia of the Queer Cinema Movement James Joseph Flaherty San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Flaherty, James Joseph, "If I Could Choose: Internalized Homophobia of the Queer Cinema Movement" (2010). Master's Theses. 3760. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.tqea-hw4y https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3760 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IF I COULD CHOOSE: INTERNALIZED HOMOPHOBIA OF THE QUEER CINEMA MOVEMENT A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Television, Radio, Film and Theatre San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by James J. Flaherty May 2010 © 2010 James J. Flaherty ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled IF I COULD CHOOSE: INTERNALIZED HOMOPHOBIA OF THE QUEER CINEMA MOVEMENT by James J. Flaherty APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF TELEVISION, FILM, RADIO AND THEATRE SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY May 2010 Dr. Alison McKee Department of Television, Film, Radio and Theatre Dr. David Kahn Department of Television, Film, Radio and Theatre Mr. Scott Sublett Department of Television, Film, Radio and Theatre ABSTRACT IF I COULD CHOOSE: INTERNALIZED HOMOPHOBIA OF THE QUEER CINEMA MOVEMENT By James J. -

PDF Schedule

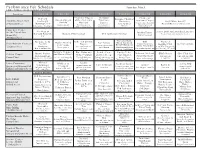

Performance Fair Schedule Saturday, May 5, 1pm - 5 pm (See also other Saturday event listings.) Location 1:00-1:20 1:30-1:50 2:00-2:20 2:30-2:50 3:00-3:20 3:30-3:50 4:00-4:20 4:30-4:50 Harvard Chamber Singers Heliodor Clerkes of Harvard Organ of the Collegium Trombone Baroque Chamber Adolphus Busch Hall University Orchestra Appleton Chapel Early Music Society Society Musicum Quartet 27 Kirkland Street Morning Choir HandelÕs ÒWater Choral music from the MozartÕs ÒBastien and BastienneÓ Organ concert Renaissance to Jazz-inspired Middle Ages and Renaissance madrigals MusicÓ 20th century music improvisation Renaissance Carpenter Center The Best of Jessica Boyd and Jonathan Laurence for the Visual Arts Dudley House Harvard-Radcliffe Student Film Festival VES Animation Festival Scenes from contemporary theater Film Festival Room BO4 TV 24 Quincy Street Gilbert & Sullivan Nicholas Bath, Harvard Baroque Cello Robbie Merfeld Sae Takada Minsu Longiaru, H-R Fogg Museum Courtyard Society Players Contemporary Juggling Club No event scheduled and Friends Selections from Satie David Miyamoto Sonatas by Music Ensemble 32 Quincy Street Selections from the and Chopin MendelssohnÕs Piano Feats that defy gravity Benedetto Marcello Piano quintet New works by students repertoire Trio no. 1 in D Minor and challenge the mind Julianna Dempsey Kate Nyhan and Jennifer Caine Lucido Felice Daniel Pietras Deborah Abel and ÕCliffe Notes Glee Club Lite Holden Chapel and Dimitri Dover Michael Callahan and Ben Steege Pops Quartet BeethovenÕs Piano Susan Davidson Jazz and pop Pop, jazz, and folk Seven early songs by HaydnÕs ÒArianna ProkofievÕs Sonata no. -

Claimed Studios Self Reliance Music 779

I / * A~V &-2'5:~J~)0 BART CLAHI I.t PT. BT I5'HER "'XEAXBKRS A%9 . AFi&Lkz.TKB 'GMIG'GCIKXIKS 'I . K IUOF IH I tt J It, I I" I, I ,I I I 681 P U B L I S H E R P1NK FLOWER MUS1C PINK FOLDER MUSIC PUBLISH1NG PINK GARDENIA MUSIC PINK HAT MUSIC PUBLISHING CO PINK 1NK MUSIC PINK 1S MELON PUBL1SHING PINK LAVA PINK LION MUSIC PINK NOTES MUS1C PUBLISHING PINK PANNA MUSIC PUBLISHING P1NK PANTHER MUSIC PINK PASSION MUZICK PINK PEN PUBLISHZNG PINK PET MUSIC PINK PLANET PINK POCKETS PUBLISHING PINK RAMBLER MUSIC PINK REVOLVER PINK ROCK PINK SAFFIRE MUSIC PINK SHOES PRODUCTIONS PINK SLIP PUBLISHING PINK SOUNDS MUSIC PINK SUEDE MUSIC PINK SUGAR PINK TENNiS SHOES PRODUCTIONS PiNK TOWEL MUSIC PINK TOWER MUSIC PINK TRAX PINKARD AND PZNKARD MUSIC PINKER TONES PINKKITTI PUBLISH1NG PINKKNEE PUBLISH1NG COMPANY PINKY AND THE BRI MUSIC PINKY FOR THE MINGE PINKY TOES MUSIC P1NKY UNDERGROUND PINKYS PLAYHOUSE PZNN PEAT PRODUCTIONS PINNA PUBLISHING PINNACLE HDUSE PUBLISHING PINOT AURORA PINPOINT HITS PINS AND NEEDLES 1N COGNITO PINSPOTTER MUSIC ZNC PZNSTR1PE CRAWDADDY MUSIC PINT PUBLISHING PINTCH HARD PUBLISHING PINTERNET PUBLZSH1NG P1NTOLOGY PUBLISHING PZO MUSIC PUBLISHING CO PION PIONEER ARTISTS MUSIC P10TR BAL MUSIC PIOUS PUBLISHING PIP'S PUBLISHING PIPCOE MUSIC PIPE DREAMER PUBLISHING PIPE MANIC P1PE MUSIC INTERNATIONAL PIPE OF LIFE PUBLISHING P1PE PICTURES PUBLISHING 882 P U B L I S H E R PIPERMAN PUBLISHING P1PEY MIPEY PUBLISHING CO PIPFIRD MUSIC PIPIN HOT PIRANA NIGAHS MUSIC PIRANAHS ON WAX PIRANHA NOSE PUBL1SHING P1RATA MUSIC PIRHANA GIRL PRODUCTIONS PIRiN -

Joan Jett & the Blackhearts

Joan Jett & the Blackhearts By Jaan Uhelszki As leader of her hard-rockin’ band, Jett has influenced countless young women to pick up guitars - and play loud. IF YOU HAD TO SIT DOWN AND IMAGINE THE IDEAL female rocker, what would she look like? Tight leather pants, lots of mascara, black (definitely not blond) hair, and she would have to play guitar like Chuck Berry’s long-lost daughter. She wouldn’t look like Madonna or Taylor Swift. Maybe she would look something like Ronnie Spector, a little formidable and dangerous, definitely - androgynous, for sure. In fact, if you close your eyes and think about it, she would be the spitting image of Joan Jett. ^ Jett has always brought danger, defiance, and fierceness to rock & roll. Along with the Blackhearts - Jamaican slang for loner - she has never been afraid to explore her own vulnerabilities or her darker sides, or to speak her mind. It wouldn’t be going too far to call Joan Jett the last American rock star, pursuing her considerable craft for the right reason: a devo tion to the true spirit of the music. She doesn’t just love rock & roll; she honors it. ^ Whether she’s performing in a blue burka for U.S. troops in Afghanistan, working for PETA, or honoring the slain Seattle singer Mia Zapata by recording a live album with Zapata’s band the Gits - and donating the proceeds to help fund the investigation of Zapata’s murder - her motivation is consistent. Over the years, she’s acted as spiritual advisor to Ian MacKaye, Paul Westerberg, and Peaches. -

Price Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price Follow Us on Twitter

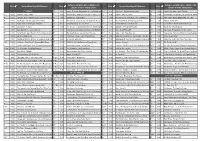

Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ updates on items selling out etc. updates on items selling out etc. 7" SINGLES 7" 14.99 Queen : Bohemian Rhapsody/I'm In Love With My Car 12" 22.99 John Grant : Remixes Are Also Magic 12" 9.99 Lonnie Liston Smith : Space Princess 7" 12.99 Anderson .Paak : Bubblin' 7" 13.99 Sharon Ridley : Where Did You Learn To Make Love The 12" Way You 11.99Do Hipnotic : Are You Lonely? 12" 10.99 Soul Mekanik : Go Upstairs/Echo Beach (feat. Isabelle Antena) 7" 16.99 Azymuth : Demos 1973-75: Castelo (Version 1)/Juntos Mais 7" Uma Vez9.99 Saint Etienne : Saturday Boy 12" 9.99 Honeyblood : The Third Degree/She's A Nightmare 12" 11.99 Spirit : Spirit - Original Mix/Zaf & Phil Asher Edit 7" 10.99 Bad Religion : My Sanity/Chaos From Within 7" 12.99 Shit Girlfriend : Dress Like Cher/Socks On The Beach 12" 13.99 Hot 8 Brass Band : Working Together E.P. 12" 9.99 Stalawa : In East Africa 7" 9.99 Erykah Badu & Jame Poyser : Tempted 7" 10.99 Smiles/Astronauts, etc : Just A Star 12" 9.99 Freddie Hubbard : Little Sunflower 12" 10.99 Joe Strummer : The Rockfield Studio Tracks 7" 6.99 Julien Baker : Red Door 7" 15.99 The Specials : 10 Commandments/You're Wondering Now 12" 15.99 iDKHOW : 1981 Extended Play EP 12" 19.99 Suicide : Dream Baby Dream 7" 6.99 Bang Bang Romeo : Cemetry/Creep 7" 10.99 Vivian Stanshall & Gargantuan Chums (John Entwistle & Keith12" Moon)14.99 : SuspicionIdles : Meat EP/Meta EP 10" 13.99 Supergrass : Pumping On Your Stereo/Mary 7" 12.99 Darrell Banks : Open The Door To Your Heart (Vocal & Instrumental) 7" 8.99 The Straight Arrows : Another Day In The City 10" 15.99 Japan : Life In Tokyo/Quiet Life 12" 17.99 Swervedriver : Reflections/Think I'm Gonna Feel Better 7" 8.99 Big Stick : Drag Racing 7" 10.99 Tindersticks : Willow (Feat. -

Marc Bolan the Best of '72-'77 - Volume Two Mp3, Flac, Wma

Marc Bolan The Best Of '72-'77 - Volume Two mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: The Best Of '72-'77 - Volume Two Country: UK Released: 1998 Style: Glam MP3 version RAR size: 1849 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1459 mb WMA version RAR size: 1164 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 689 Other Formats: MP2 MP4 DMF ASF WMA AA AIFF Tracklist 1-1 Rock On 3:26 1-2 The Slider 3:21 1-3 Baby Boomerang 2:16 1-4 Buick Mackane 3:29 1-5 Main Man 4:12 1-6 Tenement Lady 2:54 1-7 Broken-Hearted Blues 2:02 1-8 Country Honey 1:46 1-9 Electric Slim & The Factory Hen 3:02 1-10 Highway Knees 2:32 1-11 Explosive Mouth 2:26 1-12 Liquid Gang 3:17 1-13 Interstellar Soul 3:26 1-14 Solid Baby 2:36 1-15 Space Boss 2:47 1-16 Zip Gun Boogie 3:18 1-17 Think Zinc 3:20 1-18 Sensation Boulevard 3:48 1-19 Dreamy Lady 2:51 1-20 Ride My Wheels 2:25 2-1 Theme For A Dragon 2:00 2-2 Dawn Storm 3:42 2-3 Dandy In The Underworld 4:33 2-4 I'm A Fool For You Girl 2:16 2-5 I Love To Boogie 2:14 2-6 Jason B. Sad 3:22 2-7 Groove A Little 3:24 2-8 Sugar Baby 1:39 2-9 Fast Blues - Easy Action 3:22 2-10 Sky Church Music 4:15 2-11 Sad Girl 0:54 2-12 (By The Light Of A) Magical Moon 3:03 2-13 Petticoat Lane 2:42 2-14 Hot George 1:40 2-15 Classic Rap 2:14 2-16 Funky London Childhood 2:25 2-17 Jeepster [Live] 4:05 2-18 Telegram Sam [Live] 7:08 2-19 Debora [Live] 3:59 2-20 Hot Love [Live] 3:31 Companies, etc.