Kalanda - Christmas Carols in Macedonia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia

XII. The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia by Iakovos D. Michailidis Most of the reports on Greece published by international organisations in the early 1990s spoke of the existence of 200,000 “Macedonians” in the northern part of the country. This “reasonable number”, in the words of the Greek section of the Minority Rights Group, heightened the confusion regarding the Macedonian Question and fuelled insecurity in Greece’s northern provinces.1 This in itself would be of minor importance if the authors of these reports had not insisted on citing statistics from the turn of the century to prove their points: mustering historical ethnological arguments inevitably strengthened the force of their own case and excited the interest of the historians. Tak- ing these reports as its starting-point, this present study will attempt an historical retrospective of the historiography of the early years of the century and a scientific tour d’horizon of the statistics – Greek, Slav and Western European – of that period, and thus endeavour to assess the accuracy of the arguments drawn from them. For Greece, the first three decades of the 20th century were a long period of tur- moil and change. Greek Macedonia at the end of the 1920s presented a totally different picture to that of the immediate post-Liberation period, just after the Balkan Wars. This was due on the one hand to the profound economic and social changes that followed its incorporation into Greece and on the other to the continual and extensive population shifts that marked that period. As has been noted, no fewer than 17 major population movements took place in Macedonia between 1913 and 1925.2 Of these, the most sig- nificant were the Greek-Bulgarian and the Greek-Turkish exchanges of population under the terms, respectively, of the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly and the 1923 Lausanne Convention. -

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman In his speech On the Crown Demosthenes often lionizes himself by suggesting that his actions and policy required him to overcome insurmountable obstacles. Thus he contrasts Athens’ weakness around 346 B.C.E. with Macedonia’s strength, and Philip’s II unlimited power with the more constrained and cumbersome decision-making process at home, before asserting that in spite of these difficulties he succeeded in forging later a large Greek coalition to confront Philip in the battle of Chaeronea (Dem.18.234–37). [F]irst, he (Philip) ruled in his own person as full sovereign over subservient people, which is the most important factor of all in waging war . he was flush with money, and he did whatever he wished. He did not announce his intentions in official decrees, did not deliberate in public, was not hauled into the courts by sycophants, was not prosecuted for moving illegal proposals, was not accountable to anyone. In short, he was ruler, commander, in control of everything.1 For his depiction of Philip’s authority Demosthenes looks less to Macedonia than to Athens, because what makes the king powerful in his speech is his freedom from democratic checks. Nevertheless, his observations on the Macedonian royal power is more informative and helpful than Aristotle’s references to it in his Politics, though modern historians tend to privilege the philosopher for what he says or even does not say on the subject. Aristotle’s seldom mentions Macedonian kings, and when he does it is for limited, exemplary purposes, lumping them with other kings who came to power through benefaction and public service, or who were assassinated by men they had insulted.2 Moreover, according to Aristotle, the extreme of tyranny is distinguished from ideal kingship (pambasilea) by the fact that tyranny is a government that is not called to account. -

Very Short History of the Macedonian People from Prehistory to the Present

Very Short History of the Macedonian People From Prehistory to the Present By Risto Stefov 1 Very Short History of the Macedonian People From Pre-History to the Present Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2008 by Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................4 Pre-Historic Macedonia...............................................................................6 Ancient Macedonia......................................................................................8 Roman Macedonia.....................................................................................12 The Macedonians in India and Pakistan....................................................14 Rise of Christianity....................................................................................15 Byzantine Macedonia................................................................................17 Kiril and Metodi ........................................................................................19 Medieval Macedonia .................................................................................21 -

REGIONAL ACTION PLAN for the REGION of CENTRAL MACEDONIA –GREECE

REGIONAL ACTION PLAN for the REGION OF CENTRAL MACEDONIA –GREECE In the context of PURE COSMOS Project- Public Authorities Role Enhancing Competitiveness of SMEs March 2019 Development Agency of Eastern Thessaloniki’s Local Authorities- ANATOLIKI SA REGION OF CENTRAL MACEDONIA HELLENIC REPUBLIC Thessaloniki 19 /9/2019 REGION OF CENTRAL MACEDONIA, Prot. Number:. Oik.586311(1681) DIRECTORATE OF INNOVATION AND ENTREPRENEUSHIP SUPPORT Address :Vasilissis Olgas 198, PC :GR 54655, Thessaloniki, Greece Information : Mr Michailides Constantinos Telephone : +302313 319790 Email :[email protected] TO: Development Agency of Eastern Thessaloniki’s Local Authorities- ANATOLIKI SA SUBJECT: Approval of the REGIONAL ACTION PLAN for the REGION OF CENTRAL MACEDONIA –GREECE in the context of PURE COSMOS Project-“Public Authorities Role Enhancing Competitiveness of SMEs” Dear All With this letter we would like to confirm ñ that we were informed about the progress of the Pure Cosmos project throughout its phase 1, ñ that we were in regular contact with the project partner regarding the influence of the policy instrument and the elaboration of the action plan, ñ that the activities described in the action plan are in line with the priorities of the axis 1 of the ROP of Central Macedonia, ñ that we acknowledge its contribution to the expected results and impact on the ROP and specifically on the mechanism for supporting innovation and entrepreneurship of the Region of Central Macedonia, ñ that we will support the implementation of the Action Plan during -

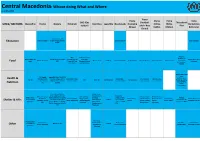

Central Macedonia: Whose Doing What and Where As of May 2016

Central Macedonia: Whose doing What and Where as of May 2016 Pieria Pieria Pieria Pieria Veria EKO (Gas (football Thessalonik Alexandria Cherso Diavata Eidomeni Giannitsa Lagadikia Nea Kavala (Camping (Ktima (Petra (Armatolou SITES/ SECTORS station) pitch- Nea i Port Nireas) Iraklis) Olybou) Kokkinou) Chrani) Humanity Crew, SOS Education Save the Children Children Villages; Save the Save the Children Veria Volunteers children Aristotele MSF, Lighthouse Refugee University of Hellenic Army; IRC Hellenic Army; IRC (cash); UNHCR,Samaritan's Relief, MSF, Hellenic Army ,Veria Hellenic Army; HRC Hellenic Army UNHCR Hellenic Army; HRC Hellenic Army Hellenic Air Force Hellenic Air Force Hellenic Army Thessaloniki, Food (cash) HRC Purse; HRC; Save Samaritan's Purse; Volunteers Hellenic Army , the children Save the children PRAKSIS Agape, Hellenic Red Cross, IFRC, Israaid, Agape,HRC,Mdm,PRAKSIS,SO MdM,National Health & PRAKSIS, WAHA, S Children Villages, WAHA; MSF; MDM; Praksis; IFRC,PRAKSIS, HRC, Voluntary HRC, Voluntary HRC; IRC MSF MDM; IRC UNHCR (MdM) HRC, Volunteers Health Operations Save the Children; MDM; Save the children; Save the children Save the Children Team of Action Team of Action Cener (EKEPY), Nutrition IRC IRC; IFRC WAHA, SolidarityNow Green Helmet, Hellenic Hellenic Army, Army, Lighthouse Refugee Evangelic church Drop in The Hellenic Army, Save MSF, Lighthouse Hellenic Air Force, Hellenic Air Force, Hellenic Army, Relief, Chef's Club - Ecopolis, of Greece, Ocean, Hellenic PRAKSIS, the Children, Terre des hommes, Refugee Relief, -

Ottoman Macedonia (Late 14Th – Late 17Th Century)

VI. Ottoman Macedonia (late 14th – late 17th century) by Phokion Kotzageorgis 1. The Ottoman conquest The Ottoman period in Macedonia begins with the region’s conquest in the late 14th cen- tury.1 The Ottoman victory against the combined Serb forces at Çirmen in Evros in 1371 was the turning point that permitted the victors to proceed with ease towards the west and, around a decade later, to cross the river Nestos and enter the geographic region of Mace- donia. 1383 marked their first great victory in Macedonia, the fall of the important administrative centre of Serres.2 By the end of the century all the strategically important Macedonian cities had been occupied (Veroia, Monastir, Vodena, Thessaloniki).3 The process by which the city of Thessaloniki was captured was somewhat different than for the others: it was initially given to the Ottomans in 1387 – after a siege of four years – and re- mained autonomous for a period. In 1394 it was fully incorporated into the Ottoman state, only to return to Byzantine hands in 1403 with the agreement they made with the Otto- mans, drawn up after the (temporary) collapse of the Ottoman state.4 In 1423 the Byzantine governor of the city, Andronikos Palaiologos, handed it over to the Venetians, and the en- suing Venetian period in Thessaloniki lasted for seven years. On 29 March 1430, the Ottoman regiments under Murad II raided and occupied the city, incorporating it fully into their state.5 Ioannis Anagnostis, eyewitness to Thessaloniki’s fall, described the moment at which the Ottomans entered the city:6 Because in those parts they found a number of our people, pluckier than the others and with large stones, they threw them down, along with the stairways, and killed many of them. -

Veria Site Snapshot 020118

VERIA SITE SNAPSHOT 2 January 2018 | Greece HIGHLIGHTS • 226 residents in the site of Veria, as of 31st of December 2017, including an unregistered family of 4. • 21 new arrivals were received throughout December from Chios and Evros border crossing. They were all provided with food and non-food items by NRC Shelter/WASH team. • 8 residents departed spontaneously and 13 under accommodation scheme. • Protection services, including Legal Assistance and Asylum Information are still provided by UNHCR, DRC, and EASO. • IRC is handling Psychosocial Support and Child Protection. Sexual/Gender-Based Violence or any other Protection cases are referred to UNHCR. • Healthcare Services are provided by Kitrinos with support from KEELPNO (public health actor). More than 60 children were vaccinated before their official starting date in Greek public schools. • The formal Kindergarten of MoE (Ministry of Education) started operating on site. • Bridge2 interrupted their activities early December (distribution of extra food, clothing, recreational activities) and stopped operating on site later the same month. • NRC Shelter/WASH program are continuously providing diesel fuel for the heating system which is operating for a total of 13 hours throughout the day. • IFRC replaced their cash-cards with new ones with extended expiration date. • NRC SMS arranged an excursion trip to Edessa waterfalls for 90 beneficiaries of the site, in the context of Geo-cultural integration activities. • Cooking contest was also held in the site and prizes awarded to the top 3 contestants by NRC SMS. • NRC SMS liaised 3 site residents with the local Municipality and helped participate in celebration for the World Human-Rights’ day in the context of social cohesion activities with the host community of Veria. -

In the Kingdom of Alexander the Great Ancient Macedonia

Advance press kit Exhibition From October 13, 2011 to January 16, 2012 Napoleon Hall In the Kingdom of Alexander the Great Ancient Macedonia Contents Press release page 3 Map of main sites page 9 Exhibition walk-through page 10 Images available for the press page 12 Press release In the Kingdom of Alexander the Great Exhibition Ancient Macedonia October 13, 2011–January 16, 2012 Napoleon Hall This exhibition curated by a Greek and French team of specialists brings together five hundred works tracing the history of ancient Macedonia from the fifteenth century B.C. up to the Roman Empire. Visitors are invited to explore the rich artistic heritage of northern Greece, many of whose treasures are still little known to the general public, due to the relatively recent nature of archaeological discoveries in this area. It was not until 1977, when several royal sepulchral monuments were unearthed at Vergina, among them the unopened tomb of Philip II, Alexander the Great’s father, that the full archaeological potential of this region was realized. Further excavations at this prestigious site, now identified with Aegae, the first capital of ancient Macedonia, resulted in a number of other important discoveries, including a puzzling burial site revealed in 2008, which will in all likelihood entail revisions in our knowledge of ancient history. With shrewd political skill, ancient Macedonia’s rulers, of whom Alexander the Great remains the best known, orchestrated the rise of Macedon from a small kingdom into one which came to dominate the entire Hellenic world, before defeating the Persian Empire and conquering lands as far away as India. -

Budapest and Thessaloniki As Slavic Cities (1800-1914): Urban Infrastructures, National Organizations and Ethnic Territories

Central and Eastern European Online Library E3 Budapest and Thessaloniki as Slavic Cities (1800-1914): Urban Infrastructures, National Organizations and Ethnic Territories <<Budapestand Thessaloniki as Slavic Cities (1800-1 914): Urban Infrastructures, National Organizations and Ethnic Territories), by Alexander Maxwell Source: Ethnologia Balkanica (Ethnologia Balkanica), issue: 09 12005, pages: 43-64, on www.ceeol.com. ETHNOLOGIA BALKANICA, VOL. 9 (2005) Budapest and Thessaloniki as Slavic Cities (1800-1914): Urban Infrastructures, National Organizations and Ethnic Territories Alexander Mmtwell, Reno (Nevada) The rise of nationalism is an essential element in nineteenth-century urban life, since the social and material conditions that give rise to nationalism first appeared in urban areas. This paper explores national movements arising in a city that (1) was dominated by another ethnic group and (2) lay outside the national ethnoterritory. Specifically, I examine Slavic national movements in Thessaloniki and Budapest1. The emergence of Slavic nationalism in these cities demonstrates that urban institutions were more important to emerging national movements than a demographically national environment. The foreign surroundings, however, seem to have affected the ideology and political strategy of early nationalists, encouraging them to seek reconciliation with other national groups. "Nationalism" had spawned several distinct and competing literatures; any author discussing the subject must describe how he or she uses the term. Follow- ing the comparative work of Miroslav Hroch (1985), I am examining the social basis of movements thatjustified their demands with reference to the "nation". But while Hroch is mainly concerned with the emergence of movements seeking political independence, I examine several Slavic patriots who fought for cultural rights, usually limpistic rights, while simultaneously defending the legitimacy of the existing state. -

The Shaping of the New Macedonia (1798-1870)

VIII. The shaping of the new Macedonia (1798-1870) by Ioannis Koliopoulos 1. Introduction Macedonia, both the ancient historical Greek land and the modern geographical region known by that name, has been perhaps one of the most heavily discussed countries in the world. In the more than two centuries since the representatives of revolutionary France introduced into western insular and continental Greece the ideas and slogans that fostered nationalism, the ancient Greek country has been the subject of inquiry, and the object of myth-making, on the part of archaeologists, historians, ethnologists, political scientists, social anthropologists, geographers and anthropogeographers, journalists and politicians. The changing face of the ancient country and its modern sequel, as recorded in the testimonies and studies of those who have applied themselves to the subject, is the focus of this present work. Since the time, two centuries ago, when the world’s attention was first directed to it, the issue of the future of this ancient Greek land – the “Macedonian Question” as it was called – stirred the interest or attracted the involvement of scientists, journalists, diplomats and politicians, who moulded and remoulded its features. The periodical cri- ses in the Macedonian Question brought to the fore important researchers and generated weighty studies, which, however, with few exceptions, put forward aspects and charac- teristics of Macedonia that did not always correspond to the reality and that served a variety of expediencies. This militancy on the part of many of those who concerned themselves with the ancient country and its modern sequel was, of course, inevitable, given that all or part of that land was claimed by other peoples of south-eastern Europe as well as the Greeks. -

The Process of Schooling of the Refugee Children in the Greek Schools

The process of schooling of the refugee children in the Greek schools Case study: Open Cultural Center as a mediator and supporter. A study carried out in the region of Central Macedonia, Northern Greece Clara Esparza Mengual, Project Manager and Researcher at Open Cultural Center Presented within the European Joint Master’s Degree Program Migration and Intercultural Mediation (Master MIM Crossing the Mediterranean) May 2018 The process of schooling of the refugee children in the Greek schools Case study: Open Cultural Center as a mediator and supporter. A study carried out in the region of Central Macedonia, Northern Greece Clara Esparza Mengual. Master MIM Crossing the Mediterranean and Open Cultural Center Introduction The current situation regarding forced migration has had an impact on European society by calling into question the preparation and capacities of governments to face the arrival of thousands of people who should have the same rights as European citizens: Basic rights such as the right to a decent housing, to receive a medical care or to access to education. This has been especially the case of countries such as Italy and Greece, who have received the main number of people running away from the war in Syria. This phenomenon has revealed the strengths and weaknesses of each country, as well as its capacity of mobilising its citizens, thereby forcing the different governments to rethink their policies and resources. In this context, new tools appear necessary in order to face the necessities of treating forced migrants as equals, providing to them the same access to basic rights as to the regular citizens. -

DENYING ETHNIC IDENTITY the Macedonians of Greece

DDDENYING EEETHNIC IIIDENTITY The Macedonians of Greece Human Rights Watch/Helsinki (formerly Helsinki Watch) Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ Los Angeles $$$ London Copyright April 1994 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 94-75891 ISBN: 1-56432-132-0 Human Rights Watch/Helsinki Human Rights Watch/Helsinki, formerly Helsinki Watch, was established in 1978 to monitor and promote domestic and international compliance with the human rights provisions of the 1975 Helsinki accords. It is affiliated with the International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights, which is based in Vienna. The staff includes Jeri Laber, executive director; Lois Whitman, deputy director; Holly Cartner and Julie Mertus, counsels; Erika Dailey, Rachel Denber, Ivana Nizich and Christopher Panico, research associates; Christina Derry, Ivan Lupis, Alexander Petrov and Isabelle Tin-Aung, associates. The advisory committee chair is Jonathan Fanton; Alice Henkin is vice chair. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments.............................................................................................................................................viii Frequently Used Abbreviations................................................................................................................... ix Introduction and Conclusions........................................................................................................................1 Background................................................................................................................................................................4