Volume 15, Issue 1, January-April

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anterograde Fixation of Inverted Oblique Medial Malleolus Fractures

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30795/jfootankle.2021.v15.1230 Case Report Anterograde fixation of inverted oblique medial malleolus fractures: case report Sávio Manhães Chami1 , Thiago Lopes Lima1 , Alexandre Bustamante Pallottino1 , Breno Jorge Scorza1 , José Sérgio Franco 1,2, Rogério Carneiro Bitar3 1. Casa de Saúde São José, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. 2. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. 3.Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil. Abstract Fractures of the medial malleolus are common, with avulsion being the main trauma mechanism. In simple transverse fractures, re- trograde fixation with interfragmentary screws is the most common means of achieving anatomical reduction and absolute stability. However, greater attention must be paid in cases of inverted oblique fractures, which make traditional fixation difficult. We report a case in which anatomical reduction and stabilization were achieved using a reduction clamp and two headless compression screws placed anteriorly, resulting in a mechanically stable, safe and effective repair. Level of Evidence V, Therapeutic Studies; Expert Opinion. Keywords: Ankle Injuries/surgery; Bone screws; Fracture fixation, internal/methods; Range of motion, articular; Treatment outcome. Introduction In the medial malleolus, variation in the direction of the fracture line is responsible for different bone injury presen- Different mechanisms of trauma to the ankle result in diffe- tations, as well as the involvement of the deltoid ligament, (1-2) rent fracture patterns and associated ligament injuries . The especially its deep portion(6). precise identification of these injuries, as well as defining the Several techniques have been described for the internal fi- direction of the fracture line, is essential for the best surgical xation of medial malleolus fractures, the most common being planning and treatment. -

Anterior Reconstruction Techniques for Cervical Spine Deformity

Neurospine 2020;17(3):534-542. Neurospine https://doi.org/10.14245/ns.2040380.190 pISSN 2586-6583 eISSN 2586-6591 Review Article Anterior Reconstruction Techniques Corresponding Author for Cervical Spine Deformity Samuel K. Cho 1,2 1 1 1 https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7511-2486 Murray Echt , Christopher Mikhail , Steven J. Girdler , Samuel K. Cho 1Department of Orthopedics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA Department of Orthopaedics, Icahn 2 Department of Neurological Surgery, Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 425 NY, USA West 59th Street, 5th Floor, New York, NY, USA E-mail: [email protected] Cervical spine deformity is an uncommon yet severely debilitating condition marked by its heterogeneity. Anterior reconstruction techniques represent a familiar approach with a range Received: June 24, 2020 of invasiveness and correction potential—including global or focal realignment in the sagit- Revised: August 5, 2020 tal and coronal planes. Meticulous preoperative planning is required to improve or prevent Accepted: August 17, 2020 neurologic deterioration and obtain satisfactory global spinal harmony. The ability to per- form anterior only reconstruction requires mobility of the opposite column to achieve cor- rection, unless a combined approach is planned. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion has limited focal correction, but when applied over multiple levels there is a cumulative ef- fect with a correction of approximately 6° per level. Partial or complete corpectomy has the ability to correct sagittal deformity as well as decompress the spinal canal when there is an- terior compression behind the vertebral body. -

Clinical Efficacy of Extended Modified Posteromedial Approach Versus

Clinical ecacy of extended modied posteromedial approach versus posterolateral approach for surgical treatment of posterior pilon fracture: a retrospective analysis Qin-Ming Zhang Aliated Hospital of Jining Medical University Hai-Bin Wang Aliated Hospital of Jining Medical University Xiao-Yan Li Aliated Hospital of Jining Medical University Feng-Long Chu Aliated Hospital of Jining Medical University Liang Han Aliated Hospital of Jining Medical University Dong-Mei Li Aliated Hospital of Jining Medical University Bin Wu ( [email protected] ) Alited Hospital of Jining Medical University https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3707-0056 Research article Keywords: posterior pilon fracture, approach, fracture xation, buttress plate Posted Date: March 30th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-19392/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/12 Abstract Background: Posterior pilon fracture is a type of ankle fracture associated with poorer treatment results compared to the conventional ankle fracture. This is partly related to the lack of consensus on the classication, approach selection, and internal xation method for this type of fracture. This study aimed to investigate the clinical ecacy of posterolateral approach versus extended modied posteromedial approach for surgical treatment of posterior pilon fracture. Methods: Data of 67 patients with posterior pilon fracture who received xation with a buttress plate between January 2015 and December 2018 were retrospectively reviewed. Patients received steel plate xation through either the posterolateral approach (n = 35, group A) or the extended modied posteromedial approach (n = 32, group B). Operation time, intraoperative blood loss, excellent and good rate of reduction, fracture healing time, American Orthopaedic Foot & Ankle Society (AOFAS) Ankle- Hindfoot Scale score, and Visual Analogue Scale score were compared between groups A and B. -

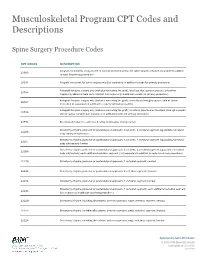

Musculoskeletal Program CPT Codes and Descriptions

Musculoskeletal Program CPT Codes and Descriptions Spine Surgery Procedure Codes CPT CODES DESCRIPTION Allograft, morselized, or placement of osteopromotive material, for spine surgery only (List separately in addition 20930 to code for primary procedure) 20931 Allograft, structural, for spine surgery only (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); local (eg, ribs, spinous process, or laminar 20936 fragments) obtained from same incision (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); morselized (through separate skin or fascial 20937 incision) (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); structural, bicortical or tricortical (through separate 20938 skin or fascial incision) (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) 20974 Electrical stimulation to aid bone healing; noninvasive (nonoperative) Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22206 body subtraction); thoracic Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22207 body subtraction); lumbar Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22208 body subtraction); each additional vertebral segment (List separately in addition to code for -

Osteotomy Around the Knee: Evolution, Principles and Results

Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc DOI 10.1007/s00167-012-2206-0 KNEE Osteotomy around the knee: evolution, principles and results J. O. Smith • A. J. Wilson • N. P. Thomas Received: 8 June 2012 / Accepted: 3 September 2012 Ó Springer-Verlag 2012 Abstract to other complex joint surface and meniscal cartilage Purpose This article summarises the history and evolu- surgery. tion of osteotomy around the knee, examining the changes Level of evidence V. in principles, operative technique and results over three distinct periods: Historical (pre 1940), Modern Early Years Keywords Tibia Osteotomy Knee Evolution Á Á Á Á (1940–2000) and Modern Later Years (2000–Present). We History Results Principles Á Á aim to place the technique in historical context and to demonstrate its evolution into a validated procedure with beneficial outcomes whose use can be justified for specific Introduction indications. Materials and methods A thorough literature review was The concept of osteotomy for the treatment of limb defor- performed to identify the important steps in the develop- mity has been in existence for more than 2,000 years, and ment of osteotomy around the knee. more recently pain has become an additional indication. Results The indications and surgical technique for knee The basic principle of osteotomy (osteo = bone, tomy = osteotomy have never been standardised, and historically, cut) is to induce a surgical transection of a bone to allow the results were unpredictable and at times poor. These realignment and a consequent transfer of weight bearing factors, combined with the success of knee arthroplasty from a damaged area to an undamaged area of joint surface. -

Periacetabular Osteotomy (PAO) of the Hip

UW HEALTH SPORTS REHABILITATION Rehabilitation Guidelines For Periacetabular Osteotomy (PAO) Of The Hip The hip joint is composed of the femur (the thigh bone) and the Lunate surface of acetabulum acetabulum (the socket formed Articular cartilage by the three pelvic bones). The Anterior superior iliac spine hip joint is a ball and socket joint Head of femur Anterior inferior iliac spine that not only allows flexion and extension, but also rotation of the Iliopubic eminence Acetabular labrum thigh and leg (Fig 1). The head of Greater trochanter (fibrocartilainous) the femur is encased by the bony Fat in acetabular fossa socket in addition to a strong, (covered by synovial) Neck of femur non-compliant joint capsule, Obturator artery making the hip an extremely Anterior branch of stable joint. Because the hip is Intertrochanteric line obturator artery responsible for transmitting the Posterior branch of weight of the upper body to the obturator artery lower extremities and the forces of Obturator membrane Ischial tuberosity weight bearing from the foot back Round ligament Acetabular artery up through the pelvis, the joint (ligamentum capitis) Lesser trochanter Transverse is subjected to substantial forces acetabular ligament (Fig 2). Walking transmits 1.3 to Figure 1 Hip joint (opened) lateral view 5.8 times body weight through the joint and running and jumping can generate forces across the joint fully form, the result can be hip that is shared by the whole hip, equal to 6 to 8 times body weight. dysplasia. This causes the hip joint including joint surfaces and the to experience load that is poorly previously-mentioned acetabular The labrum is a circular, tolerated over time, resulting in labrum. -

What Is the Impact of a Previous Femoral Osteotomy on THA?

Clin Orthop Relat Res (2019) 477:1176-1187 DOI 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000659 2018 Bernese Hip Symposium What Is the Impact of a Previous Femoral Osteotomy on THA? A Systematic Review Enrico Gallazzi MD, Ilaria Morelli MD, Giuseppe Peretti MD, Luigi Zagra MD 02/11/2020 on BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD30p/TQ0kcqx8yGZO9yTf1dd5lN9ZPVa7AUCC2fdK0Vq4= by https://journals.lww.com/clinorthop from Downloaded Downloaded from Received: 10 August 2018 / Accepted: 8 January 2019 / Published online: 17 April 2019 https://journals.lww.com/clinorthop Copyright © 2019 by the Association of Bone and Joint Surgeons Abstract by Background Femoral osteotomies have been widely used Questions/purposes In this systematic review, we asked: BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD30p/TQ0kcqx8yGZO9yTf1dd5lN9ZPVa7AUCC2fdK0Vq4= to treat a wide range of developmental and degenerative hip (1) What are the most common complications after THA in diseases. For this purpose, different types of proximal fe- patients who have undergone femoral osteotomy, and how mur osteotomies were developed: at the neck as well as at frequently do those complications occur? (2) What is the the trochanteric, intertrochanteric, or subtrochanteric lev- survival of THA after previous femoral osteotomy? (3) Is els. Few studies have evaluated the impact of a previous the timing of hardware removal associated with THA femoral osteotomy on a THA; thus, whether and how a complications and survivorship? previous femoral osteotomy affects the -

Ankle Injuries

Pediatric Fractures of the Ankle Nicholas Frane DO Zucker/Hofstra School of Medicine Northwell Health Core Curriculum V5 Disclosure • Radiographic Images Courtesy of: Dr. Jon-Paul Dimauro M.D or Christopher D Souder, MD, unless otherwise specified Core Curriculum V5 Outline • Epidemiology • Anatomy • Classification • Assessment • Treatment • Outcomes Core Curriculum V5 Epidemiology • Distal tibial & fibular physeal injuries 25%-38% of all physeal fractures • Ankle is the 2nd most common site of physeal Injury in children • Most common mechanism of injury Sports • 58% of physeal ankle fractures occur during sports activities • M>F • Commonly seen in 8-15y/o Hynes D, O'Brien T. Growth disturbance lines after injury of the distal tibial physis. Their significance in prognosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:231–233 Zaricznyj B, Shattuck LJ, Mast TA, et al. Sports-related injuries in school-aged children. Am J Sports Med. 1980;8:318–324. Core Curriculum V5 Epidemiology Parikh SN, Mehlman CT. The Community Orthopaedic Surgeon Taking Trauma Call: Pediatric Ankle Fracture Pearls and Pitfalls. J Orthop Trauma. 2017;31 Suppl 6:S27-S31. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000001014 Spiegel P, et al. Epiphyseal fractures of the distal ends of the tibia and fibula. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60(8):1046-50. Core Curriculum V5 Anatomy • Ligamentous structures attach distal to the physis • Growth plate injury more likely than ligament failure secondary to tensile weakness in physis • Syndesmosis • Anterior Tibio-fibular ligament (AITFL) • Posterior Inferior Tibio-fibular -

Total Knee Arthroplasty After Osteotomies Around the Knee

Review Article Page 1 of 5 Total knee arthroplasty after osteotomies around the knee Salvatore Risitano, Alessandro Bistolfi, Luigi Sabatini, Fabrizio Galetto, Alessandro Massè Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, Città della Salute e della Scienza, CTO Hospital, Turin 10126, Italy Contributions: (I) Conception and design: A Bistolfi, L Sabatini; (II) Administrative support: None; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: None; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: S Risitano, F Galetto; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: A Bistolfi, S Risitano; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Salvatore Risitano, MD. via Zuretti 29, Turin 10126, Italy. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Osteotomies around the knee are procedures that have shown excellent results to treat unicompartmental arthritis delaying the need for knee replacement. Despite the good results, benefits generally deteriorate with time leading to a total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for progression of osteoarthritis and involvement of the other compartments. Conversion of osteotomy to TKA is more surgically demanding compared with a primary prosthesis; in this paper, we analyze surgical difficulties that surgeons can found to perform TKA after an osteotomy around the knee; according to the literature we analyze surgical steps that can differ from standard primary surgery, including skin incision, hardware removal, residual tibial and femoral deformities and balancing of soft tissue. Keywords: Total knee arthroplasty (TKA); high tibial osteotomy (HTO); femoral osteotomy Received: 29 March 2017; Accepted: 07 April 2017; Published: 31 May 2017. doi: 10.21037/aoj.2017.05.11 View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aoj.2017.05.11 Introduction Surgical incision Osteotomies around the knee are procedures that have The knee joint is vulnerable to multiple parallel incision and shown excellent results to treat unicompartmental arthritis skin necrosis is an important issue in this surgery. -

Kyphoplasty/Vertebroplasty, Thoracic Spine

Musculoskeletal Surgical Services: Spine Fusion/Stabilization Surgery; Kyphoplasty/Vertebroplasty, Thoracic Spine POLICY INITIATED: 06/30/2019 MOST RECENT REVIEW: 06/30/2019 POLICY # HH-5641 Overview Statement The purpose of these clinical guidelines is to assist healthcare professionals in selecting the medical service that may be appropriate and supported by evidence to improve patient outcomes. These clinical guidelines neither preempt clinical judgment of trained professionals nor advise anyone on how to practice medicine. The healthcare professionals are responsible for all clinical decisions based on their assessment. These clinical guidelines do not provide authorization, certification, explanation of benefits, or guarantee of payment, nor do they substitute for, or constitute, medical advice. Federal and State law, as well as member benefit contract language, including definitions and specific contract provisions/exclusions, take precedence over clinical guidelines and must be considered first when determining eligibility for coverage. All final determinations on coverage and payment are the responsibility of the health plan. Nothing contained within this document can be interpreted to mean otherwise. Medical information is constantly evolving, and HealthHelp reserves the right to review and update these clinical guidelines periodically. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without permission -

Patient Information for Knee Osteotomy Surgery

Patient information for knee osteotomy surgery Introduction Osteoarthritis (‘wear and tear’) of the knee joint is common and can cause considerable pain and sometimes deformity of the joint. Normally when we are walking or standing, the weight goes through the centre of our knee. Unfortunately, when wear and tear affects one side of the joint, it can cause a bow leg or a knock knee. When this happens the weight is taken by the worn part of the joint, which can become more and more painful over time. This can be seen when looking at the x-rays below. On the left the weight is going through the centre of the knees and on the right it is going through the inner part of the knees, which are worn with bow legs. Normal alignment Knock knees Page 1 of 4 Treatment Early treatment can involve the use of painkillers, physical therapy, injections and weight loss, but when these options no longer control the pain adequately, a major surgical procedure may be required. Often, it is a joint replacement that is required, but this can sometimes be regarded as a risk in a young and relatively active patient due to concerns that the joint replacement may ‘wear out’ in the future, needing further surgery. Osteotomy surgery is an option that can be used instead of performing a joint replacement, particularly when the wear and tear is confined to only one side of the knee joint. The principle is that the leg is re-aligned so that more weight goes through the good side of the knee rather than the bad side that has the wear and tear. -

Hemi-Implant Arthroplasty with Decompression And

Hemi-Implant Arthroplasty with Decompression and Plantarflexion Autograft Osteotomy of the First Metatarsal Head for Hallux Limitus William Montross DPM FACFAS, Austin Brown DPM, Luc Bibeau DPM, Ankurpreet Gill DPM Statement of Purpose Results References Literature Review 1. Roukis, Thomas S. “Metatarsus Primus Elevatus in Hallux Rigidus.” Hallux limitus is often treated with hemi-implant 4 patients that underwent surgery for hallux limitus Analysis and Discussion After failure of conservative care for hallux limitus and In our cohort of patients, we were able to Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association, vol. 95, no. 3, arthroplasty to preserve range of motion while treating the rigidus, surgical gold standard for treatment is were reviewed. Mean follow up for the cohort was 2005, pp. 221–228 successfully implement a decompression and 2. Jones, Mackenzie T., et al. “Assessment of Various Measurement arthritic first metatarsal-phalangeal joint. While this arthrodesis of the great toe joint.3 Despite this, patients 20.5 months (± 7.2). At final follow up, 2 patients had procedure may treat the pain inducing element of hallux complete resolution of pain, 1 patient had continued plantarflexion osteotomy of the first metatarsal Methods to Assess First Metatarsal Elevation in Hallux Rigidus.” Foot often elect to preserve range of motion in attempts to & Ankle Orthopaedics, vol. 4, no. 3, 2019, pp. 1-9 limitus, the inherent anatomical causative factor often pain, and 1 patient did not report whether they had head with radiographic evidence of a significant salvage the joint to avoid first ray stiffness and freedom correction and complete pain relief in 2 of 4 3.