The Impact of Housing and Husbandry on the Personality of Cheetah (Acinonyx Jubatus) OPEN a C CESS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

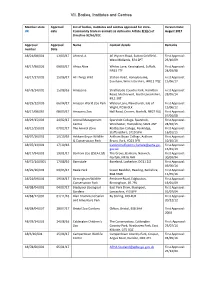

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

ATIC0943 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 0208 2257636 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0943 {By Email} 4 October 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos which we received on 26 September 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “Please can you provide me with a full list of the names of all Zoos in the UK. Under the classification of 'Zoos' I am including any place where a member of the public can visit or observe captive animals: zoological parks, centres or gardens; aquariums, oceanariums or aquatic attractions; wildlife centres; butterfly farms; petting farms or petting zoos. “Please also provide me the date of when each zoo has received its license under the Zoo License act 1981.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on current licensed zoos affected by the Zoo License Act 1981 in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 26 September 2016 (date of request). The information relating to Northern Ireland is not held by APHA. Any potential information maybe held with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland (DAERA-NI). Where there are blanks on the zoo license start date that means the information you have requested is not held by APHA. Please note that the Local Authorities’ Trading Standard departments are responsible for administering and issuing zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981. -

Annual Report 2018

Annual Report 2018 © Land of the Leopard National Park Annual Report 2018 Contents About WildCats 3 Fundraising activities 6 Generated income 8 Administration funding 9 Project funding 10 Project summaries 11 Summary of activities and impact 16 Acknowledgements 17 © NTNC 2 Annual Report 2018 About WildCats Conservation Alliance Bringing together the knowledge and experience of 21st Century Tiger and ALTA, WildCats Conservation Alliance (WildCats) is a conservation initiative implemented by Dreamworld Wildlife Foundation (DWF) and the Zoological Society of London (ZSL). Hosted by ZSL at its headquarters in Regent’s Park, London, the running costs including the salaries for the three part -time employees, are covered by an annual grant provided by DWF, continuing the support first allocated to 21st Century Tiger in 2006. This, plus the generous in-kind support provided by ZSL, enables us to continue giving 100% of donations to the wild tiger and Amur leopard conservation projects we support, which in 2018 amounted to a fantastic £261,885. Mission Statement Our mission is to save wild tigers and Amur leopards for future generations by funding carefully chosen conservation projects. We work with good zoos, individuals and companies to raise significant funds for our work and pride ourselves in providing a transparent and fair way to conserve wild cats in their natural habitat. We do this by: Raising funds that significantly contribute to the conservation of tigers and Amur leopards in the wild Selecting appropriate projects based on strict criteria agreed by the partners Raising the profile of tigers and Amur leopards and promoting public awareness of their conservation through effective communication Defining Features The conservation projects we support are carefully chosen and subjected to peer review to ensure best practice and good conservation value. -

Appendix 1 Licensed Zoos Zoo 1 Licensing Authority Macduff Marine

Appendix 1 Licensed zoos Zoo 1 Licensing Authority Macduff Marine Aquarium Aberdeenshire Council Lake District Coast Aquarium Allerdale Borough Council Lake District Wildlife Park (Formally Trotters) Allerdale Borough Council Scottish Sea Life Sanctuary Argyll & Bute Council Arundel Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust Arun Distict Council Wildlife Heritage Foundation Ashford Borough Council Canterbury Oast Trust, Rare Breeds Centre Ashford Borough Council (South of England Rare Breeds Centre) Waddesdon Manor Aviary Aylesbury Vale District Council Tiggywinkles Visitor Centre Aylesbury Vale District Council Suffolk Owl Sanctuary Babergh and Mid Suffolk District Council Safari Zoo (Formally South Lakes Wild Animal Barrow Borough Council Park) Barleylands Farm Centre Basildon District Council Wetlands Animal Park Bassetlaw District Council Chew Valley Country Farms Bath & North East Somerset District Council Avon Valley Country Park Bath & North East Somerset District Council Birmingham Wildlife Conservation Park Birmingham City Council National Sea Life Centre Birmingham City Council Blackpool Zoo Blackpool Borough Council Sea Life Centre Blackpool Borough Council Festival Park Owl Sanctuary Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Smithills Open Farm Bolton Council Bolton Museum Aquarium Bolton Council Animal World Bolton Council Oceanarium Bournemouth Borough Council Banham Zoo Ltd Breckland District Council Old MacDonalds Educational & Leisure Park Brentwood Borough Council Sea Life Centre Brighton & Hove City Council Blue Reef Aquarium Bristol City -

Licensed Zoos Zoo 1 Address Zoo 1 Zoo 1 Zoo 1 Zoo 1 Zoo 1 Zoo 1 Address 1 Licensing Authority 2 Address 3 Town/City Postcode Dispensation

APPENDIX 1 Licensed zoos Zoo 1 Address Zoo 1 Zoo 1 Zoo 1 Zoo 1 Zoo 1 Zoo 1 Address 1 Licensing Authority 2 Address 3 Town/City Postcode Dispensation Macduff 11 High Shore Macduff AB44 1SL 14.2 Aberdeenshire Council Marine Aquarium Lake District Coalbeck Farm Bassenthwaite Keswick CA12 14.2 Allerdale Borough Council Wildlife Park 4RD (Formally Trotters) Lake District South Quay Maryport CA15 14.2 Allerdale Borough Council Coast 8AB Aquarium Scottish Sea Barcaldie, By Oban PA37 1SE 14.2 Argyll & Bute Council Life Sanctuary Arundel Mill Road Arundel BN18 None Arun Distict Council Wildfowl and 9PB Wetlands Trust Wildlife Marley Farm Headcorn Smarden Ashford TN27 8PJ 14.2 Ashford Borough Council Heritage Road Foundation Canterbury Highlands Farm Woodchurch Ashford TN26 3RJ 14.2 Ashford Borough Council Oast Trust, Rare Breeds Centre (South of England Rare Breeds Centre) Waddesdon Waddesdon Waddesdon Aylesbury HP18 14.2 Aylesbury Vale District Council Manor Aviary Manor 0JH APPENDIX 1 Licensed zoos Zoo 1 Address Zoo 1 Zoo 1 Zoo 1 Zoo 1 Zoo 1 Zoo 1 Address 1 Licensing Authority 2 Address 3 Town/City Postcode Dispensation Tiggywinkles Aston Road Haddenham Aylesbury HP17 14.2 Aylesbury Vale District Council Visitor Centre 8AF The Green Claydon Road Hogshaw MK18 14.2 Aylesbury Vale District Council Dragon Rare 3LA Breeds Farm & Eco Centre Suffolk Owl Stonham Barns Pettaugh Stonham Stowmarket IP14 6AT 14.2 Babergh and Mid Suffolk District Council Sanctuary Road Aspal Wigfield Farm Haverlands Lane Worsbrough Barnsley S70 5NQ 14.1.a Barnsley Metropolitan -

Mixed-Species Exhibits with Civets and Genets (Viverridae)

MIXED-SPECIES EXHIBITS WITH CARNIVORANS IV. Mixed-species exhibits with Civets and Genets (Viverridae) Written by KRISZTIÁN SVÁBIK Assistant Curator, Budapest Zoo and Botanical Garden, Hungary Email: [email protected] 28th June 2018 Refreshed: 25th May 2020 Cover photo © Espace Zoologique de Saint-Martin-la-Plaine Mixed-species exhibits with Civets and Genets (Viverridae) 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 3 Viverrids with viverrids ........................................................................................... 4 LIST OF SPECIES COMBINATIONS – VIVERRIDAE.................................................. 5 Binturong, Arctictis binturong ............................................................................... 6 Small-toothed Palm Civet, Arctogalidia trivirgata ................................................7 Common Palm Civet, Paradoxurus hermaphroditus ............................................ 8 Masked Palm Civet, Paguma larvata .................................................................... 9 Owston’s Palm Civet, Chrotogale owstoni ............................................................10 Malayan Civet, Viverra tangalunga ...................................................................... 11 Common Genet, Genetta genetta .......................................................................... 12 Cape Genet, Genetta tigrina ................................................................................. -

A Review of Introduced Cervids in Chile

POSSIBILITY OF TWO REPRODUCTIVE SEASONS PER YEAR IN SOUTHERN PUDU (PUDU PUDA) FROM A SEMI-CAPTIVE POPULATION Fernando VidalA,B,C,G, Jo Anne M. Smith-FlueckC,D, Werner T. FlueckC,D,E, Luděk BartošF AFundación Fauna Andina Los Canelos. Casilla 102 Km 11, Villarrica, Chile. BUniversity Santo Tomas, School of Veterinarian Medicine, Conservation Unit, Temuco, Chile. CCaptive Breeding Specialist Group, IUCN/SSC. DInstitute of Natural Resources Analysis, Universidad Atlantida Argentina, Mar del Plata. Mailing address: C.C. 592, 8400 Bariloche. ENational Council of Scientific and Technological Research, Argentina; Swiss Tropical Institute, University Basel. FDepartment of Ethology, Institute of Animal Science, Praha 10 - Uhříněves, 104 01, Czech Republic. GCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Pudu (Pudu puda), occurring in the southern cone of Latin America, has been classified as vulnerable by the IUCN, yet little is known about this animal in the wild, with most knowledge on the breeding behavior coming from captive animals. For this second smallest deer in the world, delayed implantation has been suggested to explain the two peaks in the annual cycle of male sexual hormones based upon the accepted tenet that the breeding period occurs only once a year between March and June. However, in this study, birth dates from fawns born at the Los Canelos semi-captive breeding center in Chile and male courting behavior revealed possibility of two rutting periods: autumn and spring. To our knowledge, this is the first time that late fall/early winter births (May through early June) have been recorded for the southern pudu; two of these four births were conceived by females in the wild. -

November/December 2014 • Volume 58 Issue 6 January/February

November/December 2014 • Volume 58 Issue 6 January/February 2015 • Volume 59 Issue 1 TABLE OF NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2014 | VOLUME 58, ISSUE 6 contentscontents JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2015 | VOLUME 59, ISSUE 1 Features We had a Wild Time at the Animal Keeper’s 6 Safety Conference! 33 Debi Willoughby reports on topics from 33 OSHA to USDA and more. Three Cat Book Reviews 9 Pat Callahan picks out some oldies and goodies for us to read. Tales from a Tiger Groupie 10 Irving Kornheiser introduces us to experiences that shaped his life. Blast from the Past: News from Around the 18 Jungle FCF reprints margay and ocelot stories from the 1960s. Wild Cats on Postage Stamps 23 Turns out Jim Sanderson is a cat stamp collector. FCF Convention 2015 is Awaiting You in 24 Wichita, Kansas Mark your calendar for June 25 through June 27. Bobcat Trail Camera Project 26 Debi Willoughby updates her findings on native Massachusetts wildlife. Happy to be in Cougar Country 28 Peggy Jane Knight speaks for Mandala, a lucky lady puma. 2626 1818 1414 Feline Conservation Federation Volume 58, Issue 6 • Nov/Dec 2014 Volume 59, Issue 1 • Jan/Feb 2015 JOIN THE FCF IN ITS CONSERVATION EFFORTS WWW.FELINECONSERVATION.ORG A membership to the FCF entitles you to six issues of the Journal, the back-issue DVD, an invitation to FCF husbandry and wildlife education courses and annual convention, and participation in our online discussion group. The FCF works to improve captive feline husbandry and conservation. The FCF supports captive and wild habitat protection, and provides support for captive husbandry, breeding programs, and public education. -

EAZA Annual Report 2009

Annual Report 2009 Annual Report 2009 EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS AND AQUARIA 1 Annual Report 2009 Contents 3 Mission and Vision 4 Report from the Chairman 5 Report from the EAZA Executive Office 8 Aquarium Committee Report 9 Conservation Committee Report 10 Education and Exhibit Design Committee Report 11 EEP Committee Report 12 Legislation Committee Report 13 Membership & Ethics Committee Report 14 Research Committee Report 15 Technical Assistance Committee Report 16 Veterinary Committee Report 17 Treasurer’s Report 18 Financial Report 19 Governance and Organisational Structure 21 EAZA Executive Office 22 EAZA Members 29 Corporate Members Cover image: wolverine (Gulo gulo), © Peter Cairns/toothandclaw.org.uk The wolverine is one of the species covered by the EAZA European Carnivore Campaign. In September 2009 the campaign was extended for an extra year to cover a wider range of meat-eaters, bringing in raptors and marine mammals. For more information about the campaign visit: www.carnivorecampaign.eu 2 Annual Report 2009 Mission and Vision Our Mission “EAZA’s mission is to facilitate co-operation within the European zoo and aquarium community with the aim of furthering its professional quality in keeping animals and presenting them for the education of the public, and of contributing to scientific research and to the conservation of global biodiversity. It will achieve these aims through stimulation, facilitation and co-ordination of the community’s efforts in education, conservation and scientific research, through the enhancement of co-operation with all relevant organisations and through influencing relevant legislation within the EU.” (EAZA Strategy 2009-2012) Our Vision “To be the most dynamic, innovative and effective zoo and aquarium membership organisation in Europe” 3 Annual Report 2009 Report from the Chairman SImoN TONGE, CHAIrmaN Having been Chairman for all of three months what the problems are and the likely outcomes by the close of the year I feel that my major if they are not addressed. -

Licensed Zoos

Appendix 1 Licensed zoos Current licence start Zoo date Africa Alive 01 July 2008 Alladale Wilderness Reserve Alton Towers Sealife 05 March 2013 Amazon World 06 June 2008 Amazona Zoo 12 June 2012 Amazonia Anglesey Sea Zoo Animal Enterprises Ltd 14 July 2010 Animal Experience 01 April 2013 Animal Gardens 01 March 2009 Animal World 18 March 2010 Arundel Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust 09 November 2007 Auchingarrich Wildlife Centre Avon Valley Country Park 17 October 2013 Axe Valley Bird and Animal Park 01 January 2012 Banham Zoo Ltd 02 July 2013 Barleylands Farm Centre Barn Owl Centre 14 August 2008 Barnes Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust 01 June 2010 Battersea Park Childrens Zoo 16 September 2011 Battlefield Falconry Centre 24 January 2012 Baytree Owl Centre 10 July 2010 Beale Park 09 July 2008 Beaver Zoological Gardens and Reptile Rescue Ltd 26 July 2013 Beaverhall 12 February 2015 Becky Fall's Woodland Park Ltd 21 April 2010 Bentley Wildfowl Collection 01 July 2013 Berkshire College of Agriculture 13 July 2015 Birdland Park Ltd 23 January 2009 Birdworld and Underwater World 10 February 2007 Birmingham Wildlife Conservation Park 17 November 2013 Black Isle Wildlife & Country Park Blackpool Zoo 28 May 2007 Blair Drummond Safari & Adventure Park Blenheim Palace Butterfly House 11 June 2013 Blue Planet Aquarium 08 January 2013 Blue Reef 12 June 2008 Blue Reef Aquarium 05 July 2011 Blue Reef Aquarium 15 October 2013 Appendix 1 Licensed zoos Current licence start Zoo date Blue Reef Aquarium 31 March 2011 Blue Reef Aquarium 25 May 2012 Bodafon Farm Park -

EAZA Annual Report 2011

Annual Report 2011 EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS AND AQUARIA Annual Report 2011 C ontents 3 Mission and Vision 4 Report from the Chairman 5 Report from the Executive Director 9 Conservation Committee 10 Education and Exhibit Design Committee 11 Legislation Committee 12 EEP Committee 14 Membership & Ethics Committee 15 Research Committee 16 Technical Assistance Committee 17 Veterinary Committee 18 EAZA Academy 20 Treasurer’s Report 21 Financial Report 23 Governance and Organisational Structure 24 EAZA Council 25 EAZA Executive Office 26 EAZA Members 33 Corporate Members Cover image: Pink-backed pelican (Pelecanus rufescens) at Odense Zoo, © Ard Jongsma In 2010, Odense Zoo opened one of the largest aviaries in Europe, and it’s already enjoying several breeding successes 2 Annual Report 2011 Mission and Vision Our Mission “EAZA’s mission is to facilitate co-operation within the European zoo and aquarium community with the aim of furthering its professional quality in keeping animals and presenting them for the education of the public, and of contributing to scientific research and to the conservation of global biodiversity. It will achieve these aims through stimulation, facilitation and co-ordination of the community’s efforts in education, conservation and scientific research, through the enhancement of co-operation with all relevant organisations and through influencing relevant legislation within the EU.” (EAZA Strategy 2009-2012) Our Vision “To be the most dynamic, innovative and effective zoo and aquarium membership organisation in Europe” 3 Annual Report 2011 R eport from the EAZA Chairman am old enough to remember 1973 when the world as we know it nearly came to an end when the oil price doubled overnight, so it is Iwith some amazement that I observe that despite fuel prices reaching record levels the world seems to shrug and carry on regardless, and our members are no exception. -

ZSL Conservation Review 2016-17 Zsl.Org WELCOME

CONSERVATION REVIEW 2016-17 CONSERVATION ZSL Conservation Review | 2016-17 Front cover: Apo Reef in the Philippines, by ZSL’s Kirsty Richards. Below: Teeming tuna exemplify CONTENTS the ocean biodiversity ZSL is working to protect Welcome 3 Introduction 4 ZSL’s mission targets 7 ZSL’s global impact 8 Mission targets Monitoring the planet 10 Saving threatened species 14 Protecting habitats 18 Engaging with business 22 Inspiring conservation action 24 Funding and partners What you helped us achieve 28 Conservation funders 30 Conservation partners 32 Governance 34 2 ZSL Conservation Review 2016-17 zsl.org WELCOME The President and Director General of ZSL (Zoological Society of London) introduce our Conservation Review of January 2016 to April 2017. s President of ZSL, it is my pleasure to present SL’s conservation work has continued to grow in 2016, the 2016-17 Conservation Review, highlighting supported by the passion and expertise of our people. our efforts around the world to ensure a future After launching our biggest conservation partnership for wildlife. to date last year in South Sumatra – the KELOLA This year has been a positive one for the Sendang Project, intended as a model for sustainable Society, with many achievements to be proud landscape management – work is well under way to of in the conservation of animals and their address the challenges of deforestation, peatland habitats. In Nepal, where ZSL has been working degradation, wildfires and human-wildlife conflict. with government and in-country partners for decades, we were Encompassing 206 villages, 42 agribusiness concessions and 37 priority honoured to receive two awards from the Nepalese Government in species, the project landscape – and the challenges – are huge, but the recognition of our contributions, including the gratifying 90% increase opportunity is there to secure a long-term future for many threatened inA tiger numbers in Parsa Wildlife Reserve since our involvement began Zspecies, as well as a sustainable livelihood for the communities involved.