The Pennsylvania State University University Park, Pa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENGLISH Only

FOM.GAL/3/19/Rev.1 4 July 2019 ENGLISH only Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe The Representative on Freedom of the Media Harlem Désir 4 July 2019 Regular Report to the Permanent Council for the period from 22 November 2018 to 4 July 2019 1 Introduction Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen, I have the honour to present to you my latest report to the Permanent Council, which covers the period from November last year until today. In introducing this report I would like to focus on two key issues that we are facing when it comes to freedom of the media and freedom of expression. The first and greatest challenge facing journalists and other media actors which I wish to address is safety. I would like to warn, in particular, against the risk of normalization and indifference. Just two weeks ago, Vadim Komarov, a journalist from Cherkasy in Ukraine, died from his wounds following a brutal attack in May. His death did not generate much international attention or outrage, but it is no less revolting and sends a clear and sordid message of intimidation to many of his colleagues working on the same issues in the country. Komarov was investigating corruption and abuses of power in his city for many years and had been attacked in the past. He was the second journalist killed this year in the OSCE region. In April, 29-year-old journalist Lyra McKee was shot while covering riots in Northern Ireland, in the United Kingdom. She was a passionate and talented young journalist, known for her investigative reporting on the political history in the region. -

Committee of Ministers Secrétariat Du Comité Des Ministres

SECRETARIAT / SECRÉTARIAT SECRETARIAT OF THE COMMITTEE OF MINISTERS SECRÉTARIAT DU COMITÉ DES MINISTRES Contact: Zoë Bryanston-Cross Tel: 03.90.21.59.62 Date: 07/05/2021 DH-DD(2021)474 Documents distributed at the request of a Representative shall be under the sole responsibility of the said Representative, without prejudice to the legal or political position of the Committee of Ministers. Meeting: 1406th meeting (June 2021) (DH) Communication from NGOs (Public Verdict Foundation, HRC Memorial, Committee against Torture, OVD- Info) (27/04/2021) in the case of Lashmankin and Others v. Russian Federation (Application No. 57818/09). Information made available under Rule 9.2 of the Rules of the Committee of Ministers for the supervision of the execution of judgments and of the terms of friendly settlements. * * * * * * * * * * * Les documents distribués à la demande d’un/e Représentant/e le sont sous la seule responsabilité dudit/de ladite Représentant/e, sans préjuger de la position juridique ou politique du Comité des Ministres. Réunion : 1406e réunion (juin 2021) (DH) Communication d'ONG (Public Verdict Foundation, HRC Memorial, Committee against Torture, OVD-Info) (27/04/2021) dans l’affaire Lashmankin et autres c. Fédération de Russie (requête n° 57818/09) [anglais uniquement] Informations mises à disposition en vertu de la Règle 9.2 des Règles du Comité des Ministres pour la surveillance de l'exécution des arrêts et des termes des règlements amiables. DH-DD(2021)474: Rule 9.2 Communication from an NGO in Lashmankin and Others v. Russia. Document distributed under the sole responsibility of its author, without prejudice to the legal or political position of the Committee of Ministers. -

Page 01 Feb 11.Indd

www.thepeninsulaqatar.com BUSINESS | 23 SPORT | 32 GDI and Dolphin Sixes galore as Energy in deal for McCullum’s ton drilling services rescues hosts NZ SUNDAY 21 FEBRUARY 2016 • 12 Jumada I 1437 • Volume 20 • Number 6713 thepeninsulaqatar @peninsulaqatar @peninsula_qatar Haroun makes Qatar proud New online Fuel station service to shut down over register companies inflated bills The Peninsula new directive. The ministry found DOHA: As part of efforts to fur- Ministry says 11 cases of price manipulation at ther improve the ‘ease of doing petrol stations, including the Lusail business’, the Ministry of Econ- investigations case, after issuance of the circular omy and Commerce has launched revealed collusion last month, said the statement. The a new mobile service to enable the ministry had asked all fuel stations establishment of companies online between staff of the to monitor their staff to protect the — through its mobile app. outlet in Lusail and vehicle owners’ rights. The service is available on Scheming employees sometimes iPhone and Android devices under customers issue incomplete bills to motorists, the name MEC_QATAR and ena- mentioning only the price of fuel bles investors to establish firms at without specifying the quantity sold any time and from anywhere in the based on the data displayed on the world. It is part of smartphone The Peninsula meter. The ministry has asked the applications provided by the min- owners of the petrol station to abide istry to improve business processes by the law and issue bills with nec- in Qatar and streamline and speed essary information. up business incorporation proce- DOHA: In a major crackdown, the As per Article No. -

SAINT XAVIER UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE CATALOG 2019-2020 3 Requirements for B.S

Study Abroad Opportunities...........................................33 Student Success Program (SSP)...................................34 Center for Accessibility Resources.............................. 35 Counseling Center.......................................................... 36 Table of Contents Board of Trustees........................................................... 37 About Saint Xavier University......................................... 7 Life Trustees.................................................................. 37 University Mission Statement..........................................8 Administration................................................................. 38 University Core Values.....................................................9 President's Office...........................................................38 University History........................................................... 10 Academic Affairs............................................................38 Vision of Our Catholic and Mercy Identity....................11 Athletics..........................................................................39 The Sisters of Mercy...................................................... 12 Business and Finance Operations.................................39 A Brief History................................................................12 Enrollment Management, Student Development and University Celebrations of Mercy...................................12 Student Success............................................................40 -

Kuwait Times 24-10-2017.Qxp Layout 1

SAFAR 4, 1439 AH TUESDAY, OCTOBER 24, 2017 Max 35º 32 Pages 150 Fils Established 1961 Min 20º ISSUE NO: 17363 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Women empowerment is Trump ‘made me cry’, says Butter shortages bite as Patriots dominate Falcons 26strategic goal of Kuwait widow of fallen US soldier 10 French treats go global 16 in Super Bowl rematch Kuwait donates $15m as $344m pledged for Rohingya refugees Jordan queen decries ‘persecution’ • Bangladesh says burden ‘untenable’ GENEVA: Nations have pledged $344 mil- lion to care for Myanmar’s Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, an “encouraging” step in the activists allege. The two pit bulls, a response to the intensifying crisis, the UN Dogs switched breed banned in Kuwait, were import- said yesterday. Many of the funds for the ed on Sept 22. But they were not minority Muslim group, who have fled from allowed to pass through customs and violence in the northern part of Myanmar’s from customs, were instead kept in their crates in the Rakhine state, were promised at a high-level cargo terminal. conference in Geneva, co-hosted by the used in fights Only they weren’t. Sources close to United Nations, the European Union and the matter claim the animals were Kuwait. Kuwait announced its commitment to By Athoob Al-Shuaibi switched after a week in quarantine donate $15 million, offered by official and and used in local illicit dogfights. To public bodies. KUWAIT: Two dogs illegally import- prevent suspicion, two strays were Kuwait’s Deputy Foreign Minister Khaled ed to Kuwait from Romania are now rounded up and placed in the cus- Al-Jarallah said the UN Security Council is suffering in poor conditions and are toms’ hold where the two pit bulls had facing an ethical and humanitarian responsi- stuck in customs without adequate been kept. -

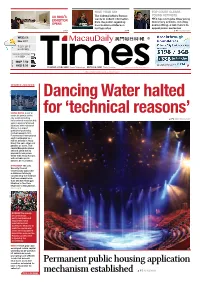

Permanent Public Housing Application Mechanism Established

HAVE YOUR SAY TOP COURT CLEARS The Cultural Affairs Bureau YOUNG ACTIVISTS XU BING’S wants to collect information HK’s top court gave three young EXHIBITION from the public regarding democracy activists, including OPENS the condition of Macau’s Joshua Wong, a last chance to heritage sites appeal prison sentences P2 P4 P11 HONG KONG WED.08 Nov 2017 T. 20º/ 26º C H. 65/ 98% facebook.com/mdtimes + 11,000 MOP 7.50 2922 N.º HKD 9.50 FOUNDER & PUBLISHER Kowie Geldenhuys EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Paulo Coutinho www.macaudailytimes.com.mo “ THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGIN’ ” WORLD BRIEFS AP PHOTO Dancing Water halted HONG KONG is set to retain its status as the for ‘technical reasons’ city most visited by P3 MDT EXCLUSIVE international travelers this year in spite of strained relations with mainland China. In a report published yesterday, market research firm Euromonitor International said it estimates 25.7 million arrivals in Hong Kong this year, down 3.2 percent on 2016. Thai capital Bangkok retains second place but its popularity has grown faster than Hong Kong’s, with arrivals up 9.5 percent at 21.3 million. MYANMAR The U.N. Security Council unanimously approved a statement strongly condemning the violence that has caused more than 600,000 Rohingya Muslims to flee from Myanmar to Bangladesh. More on p12 AP PHOTO RUSSIA Thousands of Communist party members and supporters have marched across downtown Moscow to mark the centennial of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution even as the Russian government is ignoring the anniversary. INDIA A thick gray haze enveloped India’s capital yesterday as air pollution hit hazardous levels, prompting local officials to ask that schools shut down and a half marathon scheduled for Permanent public housing application later in November be called off. -

Venue: Hofburg Congress Center on Heldenplatz, Ratsaal Room (5Th Floor)

Venue: Hofburg Congress Center on Heldenplatz, Ratsaal room (5th floor) Journalism is a dangerous profession. When Sadly, the list does however not end here. reporting at times of war and embedded in When reporting to the OSCE Permanent conflict zones, living with danger is part of the Council on his interventions made between job description. However, increasingly also July and November 2018, the OSCE journalists working in democratic societies Representative on Freedom of the Media have to live with this fear. More and more (RFoM) brought with him a list of 170 cases often, reports emanate of journalists being from the OSCE region, 53 of which related to harassed, intimidated, abducted, interrogated, the safety of journalists. This included 14 arbitrarily detained and/or imprisoned, or even cases of physical violence, two shootings, killed for the work they do. one arson attack, as well as a number of Some of the most horrifying examples include threats of physical violence. the assassination of Maltese journalist, writer Too many of these cases are either and anti- corruption activist Daphne Caruana investigated too slowly or remain without Galizia in June 2017 and Slovak investigative conclusive result. They too often end without journalist Ján Kuciak in February 2018, as perpetrators and instigators being brought to well as that of Saudi Arabian journalist Jamal justice. In 2017, the Office of the RFoM put Khashoggi in October 2018. The deaths of together a report on journalist killings in the these journalists, including the killing of five OSCE region since 1992. The result is Capital Gazette staff in June 2018 and the chilling: more than 400 journalists paid the terrorist attack against Charlie Hebdo ultimate price for their work. -

Vladimir Putin's Culture of Terror: What Is to Be Done?

University of St. Thomas Journal of Law and Public Policy Volume 9 Issue 2 Spring 2015 Article 5 January 2015 Vladimir Putin's Culture of Terror: What Is to Be Done? Charles Reid Jr. University of St. Thomas School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/ustjlpp Part of the Human Rights Law Commons Recommended Citation Charles Reid Jr., Vladimir Putin's Culture of Terror: What Is to Be Done?, 9 U. ST. THOMAS J.L. & PUB. POL'Y 275 (2015). Available at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/ustjlpp/vol9/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UST Research Online and the University of St. Thomas Journal of Law and Public Policy. For more information, please contact the Editor-in-Chief at [email protected]. VLADIMIR PUTIN'S CULTURE OF TERROR: WHAT IS TO BE DONE? DR. CHARLES REID INTRODUCTION.............. ........................ ..... 276 I. BORIS NEMTSOV ............................................... 277 II. A LONG TRAIL OF TERROR AND BLOOD ............. .......... 282 A. The Murders .............................. ..... 282 1. Sergei Yushenkov .......................... ..... 283 2. Anna Politkovskaya .............................. 284 3. Alexander Litvinenko ...................................285 B. Putin's Culture of Domestic Terror........................ 287 III. PUTIN EXPORTS HIS CULTURE OF TERROR .................... 291 A. Georgia............ ..................... ..... 292 B. Ukraine ....................................... 300 1. The Poisoning of Viktor Yushchenko .................. 300 2. 2014/2015: The Russian War On Ukraine ..... ..... 304 C. Dreams of a Greater Russia ................... ......... 318 IV. VLADIMIR PUTIN AND THE NUCLEAR TRIGGER .. .................. 329 V. WHAT IS TO BE DONE? ................................... 340 A. Russian Autocracy .........................................340 B. Support For Liberal Democracy ................... ..... 344 C. Economic Sanctions ..................................... 348 D. Diplomacy: China and India...................... -

From Journalist to Coder

FROM JOURNALIST TO CODER: THE RISE OF JOURNALIST-PROGRAMMERS _______________________________________ A Professional Project presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by YANG SUN David Herzog, Project Supervisor DECEMBER 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to gratefully thank my committee of David Herzog, Beverly Horvit and Barbara Cochran, who provided generous guidance and support for my project and internship in Washington D.C. My sincere gratitude also goes to everyone at the Investigative Reporting Workshop, where I had a wonderful summer and fall. I would not have learned so much from this internship without their help, trust and encouragement. I also want to thank my awesome parents who support my every choice unconditionally. At last, I would like to thank the Missouri School of Journalism. It changed my life and it changed how I think of journalism. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...........................................................................................ii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................1 2. WEEKLY REPORTS ...............................................................................................4 3. EVALUATION .......................................................................................................25 -

Dear Secretary Salazar

Dear Secretary Salazar: I strongly oppose the Bush administration's illegal and illogical regulations under Section 4(d) and Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, which reduce protections to polar bears and create an exemption for greenhouse gas emissions. I request that you revoke these regulations immediately, within the 60-day window provided by Congress for their removal. The Endangered Species Act has a proven track record of success at reducing all threats to species, and it makes absolutely no sense, scientifically or legally, to exempt greenhouse gas emissions -- the number-one threat to the polar bear -- from this successful system. I urge you to take this critically important step in restoring scientific integrity at the Department of Interior by rescinding both of Bush's illegal regulations reducing protections to polar bears. Sarah Bergman, Tucson, AZ James Shannon, Fairfield Bay, AR Keri Dixon, Tucson, AZ John Wright, Los Angeles, CA Bill Haskins, Sacramento, CA Ben Blanding, Lynnwood, WA Kassie Siegel, Joshua Tree, CA Sher Surratt, Middleburg Hts, OH Susan Arnot, San Francisco, CA Sigrid Schraube, Schoeneck Sarah Taylor, Ny, NY Stephanie Mitchell, Los Angeles, CA Stephan Flint, Moscow, ID Simona Bixler, Apo Ae, AE Shelbi Kepler, Temecula, CA Steve Fardys, Los Angeles, CA Mary Trujillo, Alhambra, CA Kim Crawford, NJ Shari Carpenter, Fallbrook, CA Diane Jarosy, "Letchworth Garden City,Herts" Kieran Suckling, Tucson, AZ Sheila Kilpatrick, Virginia Beach, VA Sharon Fleisher, Huntington Station, NY Steve Atkins, Bath Shawn -

Qatar Praises Kuwaiti Emir's Call for Calm

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 8 Williams survives 3-hour INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2-8, 24 COMMENT 22, 23 Ostapenko REGION 8 BUSINESS 1-8, 14-20 Barwa Real Estate posts 23,473.14 8,110.16 52.48 ARAB WORLD 8 CLASSIFIED 9-13 +199.18 -7.25 +0.58 INTERNATIONAL 9-21 SPORTS 1-8 profi t of QR1.22bn epic +0.86% -0.09% +1.12% Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 WEDNESDAY Vol. XXXVIII No. 10617 October 25, 2017 Safar 5, 1439 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Emir, Sudan president hold talks Minimum wage for In brief workers on the way reparations are under way to in- establishment of an employment sup- troduce a minimum wage for port fund, which would allow for the QATAR | Offi cial Pworkers in Qatar, HE the Min- payment of overdue wages to workers Emir sends greetings ister of Administrative Development, in cases where their employers had de- Labour and Social Aff airs Dr Issa Saad layed payments for any reason. to Zambian president al-Jafali al-Nuaimi has said. The project is currently undergoing His Highness the Emir Sheikh Tamim This would be done by taking into legislative procedures. bin Hamad al-Thani, His Highness the account the adequacy of the wage lev- Meanwhile, it was revealed that the Deputy Emir Sheikh Abdullah bin Hamad el in providing for the basic needs of total number of benefi ciaries of the al-Thani and HE the Prime Minister and workers and enabling them to live at Wage Protection System (WPS) so far Interior Minister Sheikh Abdullah bin an appropriate humanitarian level, he is 2,477,944 (2.47mn), while the total Nasser bin Khalifa al-Thani have sent explained. -

MAKING OR BREAKING the NEWS? the Influence of Putin and Trump on Journalism

MAKING OR BREAKING THE NEWS? The influence of Putin and Trump on journalism Final Project (Super-Profielwerkstuk) Sara Haverkamp 8th of January, 2018 Geography – Mrs. Klijmij Scala College Table of contents Preface .................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Exploration .............................................................................................................................. 5 1.1.1 Trump and the media .............................................................................................................. 5 1.1.2 Relations between Trump and Putin ....................................................................................... 7 1.1.3 Putin and the media ................................................................................................................ 8 1.1.4 Making or breaking the news, that’s my question .................................................................. 9 1.2 Main research question, sub-questions and hypothesis ......................................................... 10 1.2.1 Main research question ......................................................................................................... 10 1.2.2 Hypothesis ...........................................................................................................................