Despite Cultures Central Eurasia in Context Series Douglas Northrop, Editor Despite Cultures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago Old Elites Under Communism: Soviet Rule in Leninobod a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Di

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OLD ELITES UNDER COMMUNISM: SOVIET RULE IN LENINOBOD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY FLORA J. ROBERTS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables ...................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ vi A Note on Transliteration .................................................................................................. ix Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One. Noble Allies of the Revolution: Classroom to Battleground (1916-1922) . 43 Chapter Two. Class Warfare: the Old Boi Network Challenged (1925-1930) ............... 105 Chapter Three. The Culture of Cotton Farms (1930s-1960s) ......................................... 170 Chapter Four. Purging the Elite: Politics and Lineage (1933-38) .................................. 224 Chapter Five. City on Paper: Writing Tajik in Stalinobod (1930-38) ............................ 282 Chapter Six. Islam and the Asilzodagon: Wartime and Postwar Leninobod .................. 352 Chapter Seven. The -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

Birth of Tajikistan : National Identity and the Origins of the Republic

THE BIRTH OF TAJIKISTAN i THE BIRTH OF TAJIKISTAN ii THE BIRTH OF TAJIKISTAN For Suzanne Published in 2007 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com In the United States of America and Canada distributed by Palgrave Macmillan a division of St. Martin's Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © Paul Bergne The right of Paul Bergne to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. International Library of Central Asian Studies 1 ISBN: 978 1 84511 283 7 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Pvt. Ltd From camera-ready copy edited and supplied by the author THE BIRTH OF TAJIKISTAN v CONTENTS Abbreviations vii Transliteration ix Acknowledgements xi Maps. Central Asia c 1929 xii Central Asia c 1919 xiv Introduction 1 1. Central Asian Identities before 1917 3 2. The Turkic Ascendancy 15 3. The Revolution and After 20 4. The Road to Soviet Power 28 5. -

Analysis of the Situation on Inclusive Education for People with Disabilities in the Republic of Tajikistan Report on the Results of the Baseline Research

Public Organization - League of women with disabilities «Ishtirok» April - July 2018 Analysis of the situation on inclusive education for people with disabilities in the Republic of Tajikistan Report on the results of the baseline research 1 EXPRESSION OF APPRECIATION A basic study on the inclusive education of people with disabilities in the Republic of Tajikistan (RT) conducted by the Public Organization Disabled Women's League “Ishtirok”. This study was conducted under financial support from ASIA SOUTH PACIFIC ASSOCIATION FOR BASIC AND ADULT EDUCATION (ASPBAE) The research team expresses special thanks to the Executive Office of the President of the RT for assistance in collecting data at the national, regional, and district levels. In addition, we express our gratitude for the timely provision of data to the Centre for adult education of Tajikistan of the Ministry of labor, migration, and employment of population of RT, the Ministry of education and science of RT. We express our deep gratitude to all public organizations, departments of social protection and education in the cities of Dushanbe, Bokhtar, Khujand, Konibodom, and Vahdat. Moreover, we are grateful to all parents of children with disabilities, secondary school teachers, teachers of primary and secondary vocational education, who have made a significant contribution to the collection of high-quality data on the development of the situation of inclusive education for persons with disabilities in the country. Research team: Saida Inoyatova – coordinator, director, Public Organization - League of women with disabilities «Ishtirok»; Salomat Asoeva – Assistant Coordinator, Public Organization - League of women with disabilities «Ishtirok»; Larisa Alexandrova – lawyer, director of the Public Foundation “Your Choice”; Margarita Khegay – socio-economist, candidate of economic sciences. -

2012-2013 IPM CRSP Tajikistan Project

Annual Report FY 2012-13 October 1, 2012 to September 30, 2013 Development and Delivery of Ecologically-based IPM Packages in Tajikistan Project Management: Dr. Karim Maredia (PI), Michigan State University Dr. Jozef Turok, Coordinator, CGIAR/ICARDA-Project Facilitation Unit, Tashkent, Uzbekistan Wheat IPM Package: Dr. Nurali Saidov, IPM CRSP Coordinator/Research Fellow, Tajikistan Dr. Anwar Jalilov, Research Fellow, Tajikistan Dr. Doug Landis, Michigan State University Dr. Mustapha Bohssini, ICARDA, Aleppo, Syria Dr. Megan Kennelly, Kansas State University IPM Communication: Ms. Joy Landis, Michigan State University Links with IPM CRSP Global Theme Projects: Viruses: Dr. Naidu Rayapati, Washington State University Socio-Economic Impact Assessment: Dr. Mywish Maredia and Dr. Richard Bernsten, Michigan State University, Ms. Tanzila Ergasheva, Agricultural Economics Division of Tajik Academy of Agricultural Sciences, and Dr. George Norton, Virginia Tech University 1 Michigan State University (MSU) in partnership with Kansas State University, ICARDA and several local research and academic institutions and NGOs is implementing the Tajikistan IPM program. The technical objectives of the Tajikistan IPM CRSP Program are: 1. Develop ecologically based IPM packages for wheat through collaborative research and access to new technologies. 2. Disseminate IPM packages to farmers and end-users through technology transfer and outreach programs in collaboration with local NGOs and government institutions. 3. Build institutional capacity through education, training and human resource development. 4. Enhance communication, networking and linkages among local institutions in the region and with U.S. institutions, international agricultural research centers and IPM CRSP regional and global theme programs. 5. Create a “Central Asia IPM Knowledge Network” encompassing a cadre of trained IPM specialists, trainers, IPM packages, information base and institutional linkages. -

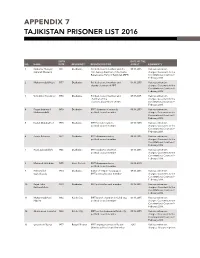

Appendix 7 Tajikistan Prisoner List 2016

APPENDIX 7 TAJIKISTAN PRISONER LIST 2016 BIRTH DATE OF THE NO. NAME DATE RESIDENCY RESPONSIBILITIES ARREST COMMENTS 1 Saidumar Huseyini 1961 Dushanbe Political council member and the 09.16.2015 Various extremism (Umarali Khusaini) first deputy chairman of the Islamic charges. Case went to the Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 2 Muhammadalii Hayit 1957 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.16.2015 Various extremism deputy chairman of IRPT charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 3 Vohidkhon Kosidinov 1956 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.17.2015 Various extremism chairman of the charges. Case went to the elections department of IRPT Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 4 Fayzmuhammad 1959 Dushanbe IRPT chairman of research, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Muhammadalii political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 5 Davlat Abdukahhori 1975 Dushanbe IRPT foreign relations, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 6 Zarafo Rahmoni 1972 Dushanbe IRPT chairman advisor, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 7 Rozik Zubaydullohi 1946 Dushanbe IRPT academic chairman, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 8 Mahmud Jaloliddini 1955 Hisor District IRPT chairman advisor, 02.10.2015 political council member 9 Hikmatulloh 1950 Dushanbe Editor of “Najot” newspaper, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Sayfullozoda IRPT political council member charges. -

An Introductory History of Soviet Uzbek Academics 1924-1960

Sevket Akyildiz Sevket Akyildiz AN INTRODUCTORY HISTORY OF SOVIET UZBEK ACADEMICS 1924-1960 INTRODUCTION It took approximately 36 years (from 1924 to 1960) to establish from scratch the Soviet Central Asian academics in Uzbekistan. The investment, organization and political commitment shown by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU, est. 1925) in the predominately Muslim region of Central Asia resulted in a highly literate and educated local population. Indeed, by the 1960s, education provision in Soviet Central Asia surpassed that found in most of the socialist and non-socialist ‘Muslim majority’ countries of Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Europe.i In this paper I will clarify the story of the local academics in the Central Asian republic with the largest population: the Soviet Socialist Republic of Uzbekistan (est. 1924). I will describe the origins of the Soviet academics and explain how they were educated, groomed and promoted by the CPSU for specific ideological, economic and cultural purposes between 1924 and 1960.1 During the historical period covered by this paper most academics employed in Uzbekistan were ethnic Slavs, Tatars or Jews. However, I will focus upon the emergence, development and integration of ethnic Uzbek academics into the higher education system during Stalin’s rule (a period when dissenting voices were purged from society) and in the decade following his death in 1953. I feel a study of the Soviet Central Asian academics is necessary because in Western literature there are some grey areas in the knowledge about the creation of local academic cadres from ‘working class’ origins in Soviet Central Asia. -

Overview of Disasters in Tajikistan 25 March - 5 May 2010

Rapid Emergency Assessment and Coordination Team – REACT Tajikistan May 6, 2010 Overview of Disasters in Tajikistan 25 March - 5 May 2010 Summary The heavy rains from 25 March to 5 May, 2010 have resulted in flooding, mudflows and landslides in 21 districts across Tajikistan. According to Committee of Emergency Situations and Civil Defense (CoES) at least 5,288 people have been affected together with over 1,000 houses, seven schools, 300 head of cattle and over 2,000 hectares of cultivated land and gardens. The kitchens and hygiene facilities of houses were either destroyed or damaged by the disasters. Over 50 kilometers of structures intended to protect housing from mud flows have been destroyed. The greatest overall damage is reported to have occurred in Vose and Muminabad districts. Damage and needs assessments were conducted for specific disasters by local and national CoES staff together with regional and national REACT members. The publically available reports can be found at http://groups.google.com/group/react_dushanbe. Local governments are submitting information on destroyed and severely damaged houses to authorities in Dushanbe to secure funds and materials for recovery activities. Specific details on the impacts and responses to the recent disasters are provided below by month of occurrence. 37/1 Bokhtar street, Dushanbe, Tajikistan, “VEFA” Business Center, 6th Floor, Suite 604 Office: (+992 47) 4410737, 4410738. www.untj.org Rapid Emergency Assessment and Coordination Team – REACT Tajikistan May 6, 2010 May 2010 Floods in Gonchi District (Sughd Province) As a result of heavy rains, at 1415 on May 5, 2010 mudflow occurred in the village Khushekat, Jamoat Rasrovud, Ghonchi District of with a population of around 3000 people (~ 700 households). -

The Tajik Civil War: 1992-1997

THE TAJIK CIVIL WAR: 1992-1997 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY SAYFIDDIN SHAPOATOV IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF EURASIAN STUDIES JUNE 2004 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences _____________________________ Prof. Dr. Sencer Ayata Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. _____________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Ceylan Tokluoğlu Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. _____________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Pınar Akçalı Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assist. Prof. Dr. Pınar Akçalı _____________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Sevilay Kahraman _____________________________ Dr. Ayça Ergun _____________________________ ABSTRACT THE TAJIK CIVIL WAR: 1992-1997 Shapoatov, Sayfiddin M.S. Department of Eurasian Studies Supervisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Pınar Akçalı June 2004, 122 pages This study aims to analyzing the role of Islam, regionalism, and external factors (the involvement of the Russian Federation, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Iran) in the Tajik Civil War (1992-97). It analyzes all these three factors one by one. In the thesis, it is argued that all of the three factors played an active and equal role in the emergence of the war and that in the case of the absence of any of these factors, the Tajik Civil War would not erupt. As such, none of the factors is considered to be the only player on its own and none of the factors is considered to be the basic result of other two factors. -

Central Asian Bolsheviks: Mediating Revolution, 1917-24

CENTRAL ASIAN BOLSHEVIKS: MEDIATING REVOLUTION, 1917-24 by PATRYK M. REID, B.A. A thesis submitted to The Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Institute of European and Russian Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario 22 September, 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-18296-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-18296-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

RP: Tajikistan: CAREC Corridor 3 (Dushanbe-Uzbekistan Border)

Land Acquisition and Resettlement Plan Land Acquisition and Resettlement Plan Project Number: 42052 June 2011 REPUBLIC OF TAJKISTAN: CAREC Corridor 3 (Dushanbe‐Uzbekistan Border) Improvement Project Prepared by the Ministry of Transport, Republic of Tajikistan, for the Asian Development Bank The Land Acquisition and Resettlement Plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. BA3OPATB 1TA p,Tki MHI-MCTEPCTBO IpAFICHOPTA tlyMXvRal I To 11 Ikt. tCI'O! PECHNIBAHKH TAAMMKPI&AH MI N lay OF TRANSPOr /.)E•R111.1 ■ 3(A: OF [A.1 K.! STJ\N 7340:2 ; M. . iliPt„ 14 . 1, ii•-n 072,12 1 ,.17-13; 2I 20'20197...LI I If l'Ac.tu,r L , - 0 -221 1010 it10001 :iaitituutopitit i I mititgoTopcTE:o Iic yrod, 'riptilkucrol-1 Ta3r,t;miel.:Ja 1,1.: , ( 3 .5010 LI ADB Mr Hong Wang Director Infrastructure Division Central and west Asia Department Subject: Grant ADB 0245-TM (SF): CAREC Corridor •3 (Dushanbe -- Uzbekistan. Border) Improvement Project Final LARP Dear Mr Hong Wang„ We Lireatly appreciate your continuous assistance and support - in transport - infrastructure projects implementation. 'Herewith we are forwarding for your approval the endorsed by the Government of . the Republic of Tajikistan «Land Acquisition and Resettlement Plan>) (Phase within • the project mentioned above. Whereas the bid for selection of contractor is an its final stage, but resettlemen t plan has to be implemented before commencement of construction works, we request for your urgent approval of submitted documentation. -

Download 598.92 KB

Grant Implementation Manual anka JFPR Number: 9111 February 2008 Republic of Tajikistan: Sustainable Access for Isolated Rural Communities (Financed by the Japan Fund for Poverty Reduction) Asian Development Bank CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 22 October 2007) Currency Unit – somoni (TJS) TJS1.00 = $0.290250 $1.00 = TJS3.44 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank CBO – community-based organization GDP – gross domestic product GIM – grant implementation memorandum IEE – initial environmental examination JFPR – Japan Fund for Poverty Reduction JRC – jamoat resource and advocacy council MOF – Ministry of Finance MOTC – Ministry of Transport and Communications NCB – national competitive bidding PIU – project implementation unit PRC – People’s Republic of China TA – technical assistance UNDP – United Nations Development Programme GLOSSARY jamoat – village cluster (the lowest administrative division) Rayon – District NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of Tajikistan ends on 31 December. (ii) In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. This Report was prepared by Hee Young Hong. Financial Analysis Specialist/Team Leader and Ana Maria A. Ignacio, Operations Officer, Central and West Asia Infrastructure Division TABLE OF CONTENTS MAP i GRANT PROCESSING HISTORY ii I. GRANT DESCRIPTION 1 A. Grant Area and Location 1 B. Grant Objectives 1 C. Grant Components 1 II. COST ESTIMATES AND FINANCING PLAN AND 4 ALLOCATION OF GRANT PROCEEDS III. IMPLEMENTATION ARRANGEMENTS 5 A. The Executing Agency and Implementing Agencies 5 B. Grant Organization and Management 5 C. Participatory Approach 6 D. Coordination with Other Donors 7 IV. IMPLEMENTATION SCHEDULE 7 V. PROCUREMENT 9 VI. CONSULTING SERVICES 9 VII. DISBURSEMENT 10 VIII. REPORTING REQUIREMENTS 10 A. Progress Reports 10 B.