Workers Versus Austerity the Origins of Ontario's 1995‐1998 'Days Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harris Disorder’ and How Women Tried to Cure It

Advocating for Advocacy: The ‘Harris Disorder’ and how women tried to cure it The following article was originally commissioned by Action Ontarienne contre la violence faite aux femmes as a context piece in training material for transitional support workers. While it outlines the roots of the provincial transitional housing and support program for women who experience violence, the context largely details the struggle to sustain women’s anti-violence advocacy in Ontario under the Harris regime and the impacts of that government’s policy on advocacy work to end violence against women. By Eileen Morrow Political and Economic Context The roots of the Transitional Housing and Support Program began over 15 years ago. At that time, political and economic shifts played an important role in determining how governments approached social programs, including supports for women experiencing violence. Shifts at both the federal and provincial levels affected women’s services and women’s lives. In 1994, the federal government began to consider social policy shifts reflecting neoliberal economic thinking that had been embraced by capitalist powers around the world. Neoliberal economic theory supports smaller government (including cuts to public services), balanced budgets and government debt reduction, tax cuts, less government regulation, privatization of public services, individual responsibility and unfettered business markets. Forces created by neoliberal economics—including the current worldwide economic crisis—still determine how government operates in Canada. A world economic shift may not at first seem connected to a small program for women in Ontario, but it affected the way the Transitional Housing and Support Program began. Federal government shifts By 1995, the Liberal government in Ottawa was ready to act on the neoliberal shift with policy decisions. -

Forward Looking Statements

TORSTAR CORPORATION 2020 ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM March 20, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS FORWARD LOOKING STATEMENTS ....................................................................................................................................... 1 I. CORPORATE STRUCTURE .......................................................................................................................................... 4 A. Name, Address and Incorporation .......................................................................................................................... 4 B. Subsidiaries ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 II. GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE BUSINESS ....................................................................................................... 4 A. Three-Year History ................................................................................................................................................ 5 B. Recent Developments ............................................................................................................................................. 6 III. DESCRIPTION OF THE BUSINESS .............................................................................................................................. 6 A. General Summary................................................................................................................................................... 6 B. -

Next Stop:?Northfield?Station | Your Online Newspaper for Waterloo

Next stop: Northfield Station | Your online newspaper for Waterloo, Ontario http://www.waterloochronicle.ca/news/next-stop northfield station/ Movies Print Editions Submit an Event Overcast 2° C | Weather Forecast Login | Register Search this Site Search Waterloo area businesses Full Text Archive Home News Sports What’s On Opinion Community Announcements Cars Classifieds Jobs Real Estate Rentals Shopping HOT TOPICS LRT RENTAL BYLAW LPGA IN YOUR NEIGHBOURHOOD CITY PARENT FAMILY SHOW Home » News » Next stop: Northfield Station Wednesday, October, 23, 2013 - 9:09:58 AM Next stop: Northfield Station By James Jackson Chronicle Staff The first two tenants of a major new development in the city’s north end have been revealed. Cineplex Digital Solutions and MNP LLP will occupy nearly half of the space available at the new Northfield Station development located at 137 and 139 Northfield Dr. W. The project is located next to a proposed light rail transit station and just minutes from the expressway. Submitted Image The total project will cost an estimated The multi-million development dubbed Northfield Station, located at 139 $9 million. Northfield Dr. W. The Zehr Group believes the presence of a light rail transit stop will be a boon to the area in the north end of the city. “They always say ‘location, location, location,’ and I believe we have arguably one of the most interesting and best locations (in the city),” said Don Zehr, chief executive officer of The Zehr Group, the local developer responsible for the site. “If you don’t want to be right downtown, this is a really cool space to be in.” Cineplex will be moving from their current Waterloo location on McMurray Road and expanding to occupy the entire 14,600 square-foot office building at 137 Northfield Dr. -

At Advertising Specs

For additional advertising information, please contact your Corporate Account Representative at Metroland Corporate Sales 10 Tempo Ave., Toronto ON M2H 2N8 Advertising Specs Media Group Ltd. Tel: 416.493.1300 • Fax: 416.493.0623 Modular Sizes TABLOID FULL PAGE THREE QUARTER - H HALF - V HALF - H THREE EIGHTS - V QUARTER - V QUARTER - H 10.375” X 11.5” 10.375” X 8.571” 5.145” x 11.5” 10.375 x 5.71” 5.145” x 8.571” 5.145” x 5.71” 10.375” x 2.786” BASEBAR SIXTH - H EIGHTH - H (FRONT PAGE OR SECTION FRONT ONLY) SIXTEENTH - H SIXTEENTH - V THIRTYSECOND 5.145” x 3.714” 5.145” x 2.786” 10.375” x 1.785” 5.145” x 1.357” 2.54” x 2.786” 2.54” x 1.357” ALL TABLOID SIZES ABOVE CAN BE USED IN THE BROADSHEET FORMATS BROADSHEET B/S FULL PAGE B/S THREE QUARTER - H B/S HALF - V B/S HALF - H B/S THREE EIGHTS - V 10.375” x 21.5” 10.375” x 16.125” 5.145” x 21.5” 10.375 x 10.75” 5.145” x 16.125” B/S QUARTER - V B/S QUARTER - H B/S FIFTH - V B/S SIXTH - H B/S EIGHTH - H 5.145” x 10.75” 10.375” x 5.375” 5.145” x 8.8” 5.145” x 7.17” 5.145” x 5.285” Dailies Columns See reverse for Niagara Modules METROLAND DAILIES - HAMILTON SPECTATOR, GUELPH MERCURY AND WATERLOO REGION RECORD - BROADSHEET 1 col. 2 col. -

The Ideology of a Hot Breakfast

The ideology of a hot breakfast: A study of the politics of the Harris governent and the strategies of the Ontario women' s movement by Tonya J. Laiiey A thesis submitted to the Department of Political Studies in confonnity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Queen's University Kingston, Ontario, Canada May, 1998 copyright 8 Tonya J. Lailey. 1998 National Library Bibl&th$aue nationaie of Canada du Cana uisitions and Acquisitions et "iBb iographk SeMces services bibliographiques 395 Wdîîngton Street 305, nie Wellington OttamON KlAONI OttawaON K1AW Canada Cenada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibiiotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, clistriiute or sel reproduire, prêter, distriiuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retahs ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract This is a study of political strategy and the womn's movement in the wake of the Harris govemment in Ontario. Through interviewhg feminist activists and by andyzhg Canadian literature on the women's movement's second wave, this paper concludes that the biggest challenge the Harris govenunent pnsents for the women's movement is ideological. -

Recruitment and Classified Advertising in Both Community and Daily Newspapers

Recruitment and &ODVVL¿HG$GYHUWLVLQJ Rate Card January 2015 10 Tempo Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M2H 2N8 tel.: 416.493.1300 fax: 416.493.0623 e:DÀLQGHUV#PHWURODQGFRP www.millionsofreaders.com www.metroland.com METROLAND MEDIA GROUP LTD. AJAX/PICKERING - HAMILTON COMMUNITY METROLAND NEWSPAPERS EDITIONS FORMAT PRESS RUNS 1 DAY 2 DAYS 3 DAYS DEADLINES, CONDITIONS AND NOTES Ajax/ Pickering News Advertiser Wed Tab 54,400 3.86 1.96 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication Thurs Tab 54,400 Alliston Herald (Modular ad sizes only) Thurs Tab 22,500 1.45 1.20 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication Almaguin News Thurs B/S 4,600 0.75 Deadline: 3 Business Days prior to publication Ancaster News/Dundas Star Thurs Tab 30,879 1.25 Deadline: 3 Business Days prior to publication Arthur Enterprise News Wed Tab 900 0.61 Deadline: 3 Business Days prior to publication Barrie Advance/Innisfil/Journal Thurs Tab 63,800 2.95 2.33 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication (Modular ad sizes only) Belleville News Thurs Tab 23,715 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication Bloor West Villager Thurs Tab 34,300 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication Bracebridge Examiner Thurs Tab 8,849 1.40 Deadline: 3 Business Days prior to publication Bradford West Gwillimbury Topic Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication - Material & Thurs Tab 10,700 1.00 (Modular ad sizes only) Booking **Process Color add 25%, Spot add 15%, up to $350 Brampton Guardian/ Wed Tab 240,500 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication. -

National Newspaper Awards Concours Canadien De Journalisme

NATIONAL NEWSPAPER AWARDS CONCOURS CANADIEN DE JOURNALISME FINALISTS/FINALISTES - 2012 Multimedia Feature/Reportage multimédia Investigations/Grande enquête La Presse, Montréal The Canadian Press Steve Buist, Hamilton Spectator The Globe and Mail Isabelle Hachey, La Presse, Montréal Winnipeg Free Press Huffington Post team David Bruser, Jesse McLean, Toronto Star News Feature Photography/Photographie de reportage d’actualité Arts and Entertainment/Culture Tyler Anderson, National Post Aaron Elkaim, The Canadian Press J. Kelly Nestruck, The Globe and Mail Lyle Stafford, Victoria Times-Colonist Stephanie Nolen, The Globe and Mail Sylvie St-Jacques, La Presse, Montreal Beats/Journalisme spécialisé Sports/Sport Jim Bronskill, The Canadian Press Sharon Kirkey, Postmedia News David A. Ebner, The Globe and Mail Heather Scoffield, The Canadian Press Dave Feschuk, Toronto Star Mary Agnes Welch, Winnipeg Free Press Roy MacGregor, The Globe and Mail Explanatory work/Texte explicatif Feature Photography/Photographie de reportage James Bagnall, Ottawa Citizen Tyler Anderson, National Post Ian Brown, The Globe and Mail Peter Power, The Globe and Mail Mary Ormsby, Toronto Star Tim Smith, Brandon Sun Politics/Politique International /Reportage à caractère international Linda Gyulai, The Gazette, Montreal Agnès Gruda, La Presse, Montréal Stephen Maher, Glen McGregor, Postmedia News/The Ottawa Michèle Ouimet, La Presse, Montréal Citizen Geoffrey York, The Globe and Mail Peter O’Neil, The Vancouver Sun Editorials/Éditorial Short Features/Reportage bref David Evans, Edmonton Journal Erin Anderssen, The Globe and Mail Jordan Himelfarb, Toronto Star Jayme Poisson, Toronto Star John Roe, Waterloo Region Record Lindor Reynolds, Winnipeg Free Press Editorial Cartooning/Caricature Local Reporting/Reportage à caractère local Serge Chapleau, La Presse, Montréal Cam Fortems, Michele Young, Kamloops Daily News Andy Donato, Toronto Sun Susan Gamble, Brantford Expositor Brian Gable, The Globe and Mail Barb Sweet, St. -

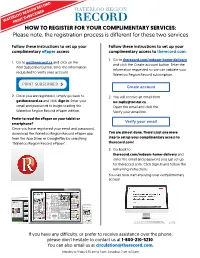

HOW to REGISTER for YOUR COMPLIMENTARY SERVICES: Please Note, the Registration Process Is Different for These Two Services

WATERLOOPRINT REGIONSUBSCRIBER RECORD HOW TO REGISTER FOR YOUR COMPLIMENTARY SERVICES: Please note, the registration process is different for these two services Follow these instructions to set up your Follow these instructions to set up your complimentary ePaper access: complimentary access to therecord.com: 1. Go to therecord.com/redeem-home-delivery 1. Go to gettherecord.ca and click on the and click the Create account button. Enter the Print Subscriber button. Enter the information information requested so we can validate your requested to verify your account. Waterloo Region Record subscription. PRINT SUBSCRIBER Create account 2. Once you are registered, simply go back to 2. You will receive an email from gettherecord.ca and click Sign in. Enter your [email protected]. email and password to begin reading the Open the email and click the Waterloo Region Record ePaper edition. Verify your email link. Prefer to read the ePaper on your tablet or smartphone? Verify your email Once you have registered your email and password, download the Waterloo Region Record ePaper app You are almost done. There’s just one more from the App Store or GooglePlay by searching step to set up your complimentary access to “Waterloo Region Record ePaper”. therecord.com! 3. Go back to therecord.com/redeem-home-delivery and enter the email and password you just set up for therecord.com. Click Sign in and follow the remaining instructions. You can now start enjoying your complimentary access! Isolated showers High 16 Details, B12 TUESDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2019 SERVING KITCHENER, WATERLOO, CAMBRIDGE AND THE TOWNSHIPS Community Waterloo and Cambridge now centres sit candidates for cannabis shops empty, but groups can’t access space Kitchener’s recreation staff outlines proposed changes to policies CATHERINE THOMPSON WATERLOO REGION RECORD KITCHENER — Many community groups have trouble getting ac- cess to meeting rooms, gyms and other space at Kitchener community centres, even though the centres sit empty the vast majority of the time. -

Overview of Results: Fall 2020 Study STUDY SCOPE – Fall 2020 10 Provinces / 5 Regions / 40 Markets • 32,738 Canadians Aged 14+ • 31,558 Canadians Aged 18+

Overview of Results: Fall 2020 Study STUDY SCOPE – Fall 2020 10 Provinces / 5 Regions / 40 Markets • 32,738 Canadians aged 14+ • 31,558 Canadians aged 18+ # Market Smpl # Market Smpl # Market Smpl # Provinces 1 Toronto (MM) 3936 17 Regina (MM) 524 33 Sault Ste. Marie (LM) 211 1 Alberta 2 Montreal (MM) 3754 18 Sherbrooke (MM) 225 34 Charlottetown (LM) 231 2 British Columbia 3 Vancouver (MM) 3016 19 St. John's (MM) 312 35 North Bay (LM) 223 3 Manitoba 4 Calgary (MM) 902 20 Kingston (LM) 282 36 Cornwall (LM) 227 4 New Brunswick 5 Edmonton (MM) 874 21 Sudbury (LM) 276 37 Brandon (LM) 222 5 Newfoundland and Labrador 6 Ottawa/Gatineau (MM) 1134 22 Trois-Rivières (MM) 202 38 Timmins (LM) 200 6 Nova Scotia 7 Quebec City (MM) 552 23 Saguenay (MM) 217 39 Owen Sound (LM) 200 7 Ontario 8 Winnipeg (MM) 672 24 Brantford (LM) 282 40 Summerside (LM) 217 8 Prince Edward Island 9 Hamilton (MM) 503 25 Saint John (LM) 279 9 Quebec 10 Kitchener (MM) 465 26 Peterborough (LM) 280 10 Saskatchewan 11 London (MM) 384 27 Chatham (LM) 236 12 Halifax (MM) 457 28 Cape Breton (LM) 269 # Regions 13 St. Catharines/Niagara (MM) 601 29 Belleville (LM) 270 1 Atlantic 14 Victoria (MM) 533 30 Sarnia (LM) 225 2 British Columbia 15 Windsor (MM) 543 31 Prince George (LM) 213 3 Ontario 16 Saskatoon (MM) 511 32 Granby (LM) 219 4 Prairies 5 Quebec (MM) = Major Markets (LM) = Local Markets Source: Vividata Fall 2020 Study 2 Base: Respondents aged 18+. -

2018 Newsletters

Waterloo Historical Society Newsletter JANUARY 2018 Marion Roes, Editor Public Meetings – All are welcome! Tuesday, March 20 at 7:30 Victoria Park Pavilion Doors open at 7 80 Schneider Ave., Kitchener Last year, for the April meeting, WHS turned over the meeting to TUGSA / Tri University Graduate Student Association. There were four excellent speakers who gave brief talks on their history research. The Tri-U History Program covers the universities of Waterloo, Laurier and Guelph, and brings together master and doctoral students for social, academic and learning opportunities. http://www.triuhistory.ca/tugsa/executive/. TUGSA members are returning for this meeting! Topics and speakers will on the WHS web site and Facebook page in February and in the April newsletter. www.whs.ca Saturday, May 12 Waterloo Region Museum Meeting and speaker at 1:30 in the Christie Digital Theatre 10 Huron Road, Kitchener Joint day-long event with the Waterloo Regional Heritage Foundation and the Waterloo Region Museum Curtis B. Robinson, PhD Candidate, Memorial University of Newfoundland, will be our speaker. If his name is familiar, it’s because WHS Volume 104-2016 includes his article, “Conflict or Consensus? The Berliner Journal and the Chief Press Censor During the First World War, 1915-1918.” Curtis is studying social history of intelligence and recruiting in German-Canadian Ontario. His topic for the meeting is “Security Measures in Southern Ontario in the First World War: An Historical Comparison.” His research has shown that security on the home front was handled differently in Southwestern Ontario than it was in Central Ontario, or rather within the confines of Military Districts 1 and 2. -

Old Bones: a Recent History of Urban Placemaking in Kitchener, Ontario

Old Bones: A recent history of urban placemaking in Kitchener, Ontario through media analysis by Lee Barich A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Planning Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2020 © Lee Barich 2020 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract Kitchener, Ontario has experienced significant social and physical changes in its downtown in recent decades. Once an industrial hub, the City's urban core declined as suburban migration and deindustrialization gutted its economic and cultural activity. Now, the downtown sees a new light rail transit (LRT) system pass by the old brick industrial buildings where tech companies and new developments thrive. This thesis will offer a historical review as to how this transition occurred through media analysis. Newspaper archives show that this revitalization was the process of negotiating place, identity, and value amongst the City's leaders, its residents, and investors. This process revolved around the successful conservation of cultural heritage sites. Participants considered how to leverage these assets to reclaim the City's identity while also building a liveable space for its future. By exploring the important role played by heritage conservation in the City's downtown revival, readers will see how cultural assets can offer an economic, social, and cultural return on investment. -

2017 Annual Report Annual 2017 Torstar

TORSTAR 2017 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2017 TORSTAR 202017 ANNUAL REPORT TORSTAR CORPORATION 2017 ANNUAL REPORT PB FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS 2017 2016 OPERATING RESULTS ($000) Operating revenue $615,685 $685,099 Segmented operating revenue (1) 691,600 761,697 Segmented Adjusted EBITDA (1) 74,209 60,478 Operating earnings (loss) (1) 7,161 (14,428) Operating loss (18,484) (61,051) Net loss (29,288) (74,836) Cash provided by (used in) operating activities 15,404 (10,599) Segmented Adjusted EBITDA - Percentage of segmented operating revenue (1) 10.7% 7.9% PER CLASS A AND CLASS B SHARES Net loss ($0.36) ($0.93) Dividends $0.10 $0.18 Price range (high/low) $2.10/$1.20 $2.90/$1.39 FINANCIAL POSITION ($000) Cash and cash equivalents and restricted cash $80,433 $87,221 Equity $245,830 $326,170 The Annual Meeting of shareholders will be held Wednesday, May 9, 2018 at The Toronto Star Building, 3rd Floor Auditorium, One Yonge Street, Toronto, beginning at 10 a.m. It will also be webcast live on the Internet. OPERATING REVENUE ($MILLIONS) OPERATING EARNINGS (LOSS) ($MILLIONS) (1) 15 787 15 21 16 685 (14) 16 17 616 17 7 N MET I CO E (LOSS) PER SHARE SEGMENTED ADJUSTED EBITDA ($MILLIONS) (1) (5.02) 15 15 69 (0.93) 16 16 60 (0.36) 17 17 74 (1) These are non-IFRS measures. These along with other Non-IFRS measures appear in the President’s message. Refer to page 37 for a reconciliation of IFRS measures. This annual report contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, including the “safe harbour“ provisions of the Securities Act (Ontario).