In Greece, Case Study Athens Supervisor: Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION Tel.: 2103202049, Fax: 2103226371

LIST OF BANK BRANCHES (BY HEBIC) 30/06/2015 BANK OF GREECE HEBIC BRANCH NAME AREA ADDRESS TELEPHONE NUMBER / FAX 0100001 HEAD OFFICE SECRETARIAT ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202049, fax: 2103226371 0100002 HEAD OFFICE TENDER AND ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS PROCUREMENT SECTION tel.: 2103203473, fax: 2103231691 0100003 HEAD OFFICE HUMAN ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS RESOURCES SECTION tel.: 2103202090, fax: 2103203961 0100004 HEAD OFFICE DOCUMENT ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202198, fax: 2103236954 0100005 HEAD OFFICE PAYROLL ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202096, fax: 2103236930 0100007 HEAD OFFICE SECURITY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202101, fax: 210 3204059 0100008 HEAD OFFICE SYSTEMIC CREDIT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS INSTITUTIONS SUPERVISION SECTION A tel.: 2103205154, fax: …… 0100009 HEAD OFFICE BOOK ENTRY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECURITIES MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202620, fax: 2103235747 0100010 HEAD OFFICE ARCHIVES ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202206, fax: 2103203950 0100012 HEAD OFFICE RESERVES ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT BACK UP SECTION tel.: 2103203766, fax: 2103220140 0100013 HEAD OFFICE FOREIGN ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS EXCHANGE TRANSACTIONS SECTION tel.: 2103202895, fax: 2103236746 0100014 HEAD OFFICE SYSTEMIC CREDIT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS INSTITUTIONS SUPERVISION SECTION B tel.: 2103205041, fax: …… 0100015 HEAD OFFICE PAYMENT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS SYSTEMS OVERSIGHT SECTION tel.: 2103205073, fax: …… 0100016 HEAD OFFICE ESCB PROJECTS CHALANDRI 341, Mesogeion Ave., 152 31 CHALANDRI AUDIT SECTION tel.: 2106799743, fax: 2106799713 0100017 HEAD OFFICE DOCUMENTARY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. -

The Hellenic Culture Centre Athens & Santorini Island, Greece

ERASMUS STUDENT PLACEMENTS THE HELLENIC CULTURE CENTRE ATHENS & SANTORINI ISLAND, GREECE WHO/ WHERE: A. The Hellenic Culture Centre www.hcc.edu.gr , founded in 1995, is one of the first non formal education institutions that offered Greek as a foreign/second language courses. It has an expertise in Language Teacher Training programmes. The aims of the institution are to promote language learning and language teaching and to contribute to adult education and intercultural education methodology. Has been involved in different national and EU projects on intercultural education, teacher training, cultural exchanges, e-learning. The Hellenic Culture Centre offers four internship posts for Erasmus students, for its offices in Athens and Santorini island, Greece: 1. Marketing coordinator To coordinate and implement a Marketing programme for new students recruitment, especially through the Internet, to work on the website, to upload materials and create newsletters, to translate texts into her/ his mother tongue 2. EU funding assistant To assist in developing proposals for EU funded projects under the Life Long Learning Programme, and to assist in implement projects that are on the way (monitor printing and production of materials, monitor on time implementation of events, monitor on time delivery of products/ deliverables, monitor expenses according to budget), to evaluate proposals and provide feedback. 3. E-learning expert To develop the e-learning platform of HCC. To coordinate the social networks of HCC. To create didactic materials for e-learning. To work on e-learning projects and develop new projects 4. Cultural Officer To develop a cultural programme in Athens & in Santorini complementary to the language programme, to develop training materials for cultural presentations (in English), to accompany students to cultural visits. -

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

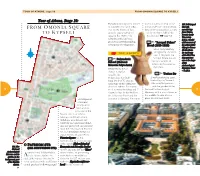

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

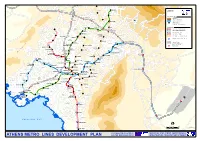

Athens Metro Lines Development Plan and the European Union Transport and Networks

Kifissia M t . P e Zefyrion Lykovrysi KIFISSIA n t LEGEND e l i Metamorfosi KAT METRO LINES NETWORK Operating Lines Pefki Nea Penteli LINE 1 Melissia PEFKI LINE 2 Kamatero MAROUSSI LINE 3 Iraklio Extensions IRAKLIO Penteli LINE 3, UNDER CONSTRUCTION NERANTZIOTISSA OTE AG.NIKOLAOS Nea LINE 2, UNDER DESIGN Filadelfia NEA LINE 4, UNDER DESIGN IONIA Maroussi IRINI PARADISSOS Petroupoli Parking Facility - Attiko Metro Ilion PEFKAKIA Nea Vrilissia Ionia ILION Aghioi OLYMPIAKO "®P Operating Parking Facility STADIO Anargyri "®P Scheduled Parking Facility PERISSOS Nea PALATIANI Halkidona SUBURBAN RAILWAY NETWORK SIDERA Suburban Railway DOUK.PLAKENTIAS Anthousa ANO Gerakas PATISSIA Filothei "®P Suburban Railway Section also used by Metro o Halandri "®P e AGHIOS HALANDRI l P "® ELEFTHERIOS ALSOS VEIKOU Kallitechnoupoli a ANTHOUPOLI Galatsi g FILOTHEI AGHIA E KATO PARASKEVI PERISTERI GALATSI Aghia . PATISSIA Peristeri P Paraskevi t Haidari Psyhiko "® M AGHIOS NOMISMATOKOPIO AGHIOS Pallini ANTONIOS NIKOLAOS Neo PALLINI Pikermi Psihiko HOLARGOS KYPSELI FAROS SEPOLIA ETHNIKI AGHIA AMYNA P ATTIKI "® MARINA "®P Holargos DIKASTIRIA Aghia PANORMOU ®P KATEHAKI Varvara " EGALEO ST.LARISSIS VICTORIA ATHENS ®P AGHIA ALEXANDRAS " VARVARA "®P ELEONAS AMBELOKIPI Papagou Egaleo METAXOURGHIO OMONIA EXARHIA Korydallos Glyka PEANIA-KANTZA AKADEMIA GOUDI Nera "®P PANEPISTIMIO MEGARO MONASTIRAKI KOLONAKI MOUSSIKIS KORYDALLOS KERAMIKOS THISSIO EVANGELISMOS ZOGRAFOU Nikea SYNTAGMA ANO ILISSIA Aghios PAGRATI KESSARIANI Ioannis ACROPOLI NEAR EAST Rentis PETRALONA NIKEA Tavros Keratsini Kessariani SYGROU-FIX KALITHEA TAVROS "®P NEOS VYRONAS MANIATIKA Spata KOSMOS Pireaus AGHIOS Vyronas s MOSCHATO Peania IOANNIS o Dafni t Moschato Ymittos Kallithea ANO t Drapetsona i PIRAEUS DAFNI ILIOUPOLI FALIRO Nea m o Smyrni Y o Î AGHIOS Ilioupoli DIMOTIKO DIMITRIOS . -

Cultural Heritage in the Realm of the Commons: Conversations on the Case of Greece

CHAPTER 10 Commoning Over a Cup of Coffee: The Case of Kafeneio, a Co-op Cafe at Plato’s Academy Chrysostomos Galanos The story of Kafeneio Kafeneio, a co-op cafe at Plato’s Academy in Athens, was founded on the 1st of May 2010. The opening day was combined with an open, self-organised gather- ing that emphasised the need to reclaim open public spaces for the people. It is important to note that every turning point in the life of Kafeneio was somehow linked to a large gathering. Indeed, the very start of the initiative, in September 2009, took the form of an alternative festival which we named ‘Point Defect’. In order to understand the choice of ‘Point Defect’ as the name for the launch party, one need only look at the press release we made at the time: ‘When we have a perfect crystal, all atoms are positioned exactly at the points they should be, for the crystal to be intact; in the molecular structure of this crystal everything seems aligned. It can be, however, that one of the atoms is not at place or missing, or another type of atom is at its place. In that case we say that the crystal has a ‘point defect’, a point where its struc- ture is not perfect, a point from which the crystal could start collapsing’. How to cite this book chapter: Galanos, C. 2020. Commoning Over a Cup of Coffee: The Case of Kafeneio, a Co-op Cafe at Plato’s Academy. In Lekakis, S. (ed.) Cultural Heritage in the Realm of the Commons: Conversations on the Case of Greece. -

Athens Guide

ATHENS GUIDE Made by Dorling Kindersley 27. May 2010 PERSONAL GUIDES POWERED BY traveldk.com 1 Top 10 Athens guide Top 10 Acropolis The temples on the “Sacred Rock” of Athens are considered the most important monuments in the Western world, for they have exerted more influence on our architecture than anything since. The great marble masterpieces were constructed during the late 5th-century BC reign of Perikles, the Golden Age of Athens. Most were temples built to honour Athena, the city’s patron goddess. Still breathtaking for their proportion and scale, both human and majestic, the temples were adorned with magnificent, dramatic sculptures of the gods. Herodes Atticus Theatre Top 10 Sights 9 A much later addition, built in 161 by its namesake. Acropolis Rock In summer it hosts the Athens Festival (see Festivals 1 As the highest part of the city, the rock is an ideal and Events). place for refuge, religion and royalty. The Acropolis Rock has been used continuously for these purposes since Dionysus Theatre Neolithic times. 10 This mosaic-tiled theatre was the site of Classical Greece’s drama competitions, where the tragedies and Propylaia comedies by the great playwrights (Aeschylus, 2 At the top of the rock, you are greeted by the Sophocles, Euripides) were first performed. The theatre Propylaia, the grand entrance through which all visitors seated 15,000, and you can still see engraved front-row passed to reach the summit temples. marble seats, reserved for priests of Dionysus. Temple of Athena Nike (“Victory”) 3 There has been a temple to a goddess of victory at New Acropolis Museum this location since prehistoric times, as it protects and stands over the part of the rock most vulnerable to The Glass Floor enemy attack. -

Nea Paralias 51 - Juli 2018 3

Nea Paralias . Dertiende jaargang - Nummer 51 - Juli 2018 . Lees in dit nummer ondermeer : . 3 Voorwoord De voorbeschouwingen van André, onze voorzitter . 3 Uw privacy Eleftheria Paralias en de nieuwe privacywetgeving . 4 Agenda De komende activiteiten, o.a. voordracht, uitstap, kookavond, enz… . 8 Ledennieuws In de kijker: ons muzikaal lid Carl Deseyn . 10 Terugblik Nabeschouwingen over de drie laatste activiteiten . 12 Dialecten en accenten Mopje uit Kreta, in het dialect, met een verklarende uitleg . 14 Actueel Drie maanden wel en wee in Griekenland . 26 Zeg nooit… Er zijn woorden die je maar beter niet uitspreekt . Een drankje uit Corfu, het Aristoteles-menu . 27 Culinair en 3 nieuwe recepten van Johan Vroomen . Inspiratie nodig voor een cadeautje voor je schoonmoeder? Op andere . 29 Griekse humor pagina’s: Remedie tegen kaalheid, Standbeeld . 30 Reisverslag De EP-groepsreis Kreta 2016 deel 5 . Pleinen en buurten Namen van pleinen, straten en buurten hebben meestal een . 32 achtergrond, maar zoals overal weten lokale bewoners niet waarom . van Athene die namen werden gegeven of hoe ze zijn ontstaan . Over de 5.000-drachme brug, ’s werelds oudste olijfboom, . 35 Wist je dat… en andere wetenswaardigheden . Ondermeer de Griekse deelname aan het songfestival . 36 Muziekrubriek en een Kretenzische parodie die een grote hit is . 38 Bestemmingen Reistips en bezienswaardigheden . Bouboulina, de laatste ambachtelijke bladerdeegbakker, . 40 Merkwaardige Grieken . en de Dame van Ro . 43 George George en afgeleide namen zijn de populairste namen voor mannen . 44 Unieke tradities De Botides, het jaarlijkse pottenbreken op Corfu . 44 Links Onze selectie websites die we de voorbije maanden bezochten; . eveneens links naar mooie YouTube-video’s . -

The Case of Athens During the Refugee Crisis

The Newcomers’ Right to the Common Space: The case of Athens during the refugee crisis Charalampos Tsavdaroglou Post-Doc Department of Planning and Regional Development School of Engineering, University of Thessaly [email protected] Abstract The ongoing refugee streams that derive from the recent conflict in the Middle East are a central issue to the growing socio-political debate about the different facets of contemporary crisis. While borders, in the era of globalization, constitute porous passages for capital goods and labor market, at the same time they function as new enclosures for migrant and refugee populations. Nevertheless, these human flows contest border regimes and exclusionary urban policies and create a nexus of emerging common spaces. Following the recent spatial approaches on “commons” and “enclosures” (Dellenbaugh et al., 2015; Harvey, 2012; Stavrides, 2016) this paper focuses on the dialectic between the refugees’ solidarity housing commons and the State-run refugee camps. Particularly, I examine the case of Greece, a country that is situated in the South-East-End of the European Union close to Asia and Africa; hence it is in the epicenter of the current refugee crisis and I pinpoint in the case of Athens, the capital of Greece and the main refugee transit city. Il diritto allo spazio comune dei nuovi arrivati: il caso di Atene durante la crisi dei rifugiati L’aumento dei flussi di migranti derivante dal recente conflitto in Medio Oriente rappresenta un tema centrale nel crescente dibattito socio-politico sulle diverse Published with Creative Commons licence: Attribution–Noncommercial–No Derivatives ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 2018, 17(2): 376-401 377 sfaccettature della crisi attuale. -

Athens Metro Lines Development Plan and the European Union Infrastructure, Transport and Networks

AHARNAE Kifissia M t . P ANO Lykovrysi KIFISSIA e LIOSIA Zefyrion n t LEGEND e l i Metamorfosi KAT OPERATING LINES METAMORFOSI Pefki Nea Penteli LINE 1, ISAP IRAKLIO Melissia LINE 2, ATTIKO METRO LIKOTRIPA LINE 3, ATTIKO METRO Kamatero MAROUSSI METRO STATION Iraklio FUTURE METRO STATION, ISAP Penteli IRAKLIO NERATZIOTISSA OTE EXTENSIONS Nea Filadelfia LINE 2, UNDER CONSTRUCTION KIFISSIAS NEA Maroussi LINE 3, UNDER CONSTRUCTION IRINI PARADISSOS Petroupoli IONIA LINE 3, TENDERED OUT Ilion PEFKAKIA Nea Vrilissia LINE 2, UNDER DESIGN Ionia Aghioi OLYMPIAKO PENTELIS LINE 4, UNDER DESIGN & TENDERING AG.ANARGIRI Anargyri STADIO PERISSOS Nea "®P PARKING FACILITY - ATTIKO METRO Halkidona SIDERA DOUK.PLAKENTIAS Anthousa Suburban Railway Kallitechnoupoli ANO Gerakas PATISSIA Filothei Halandri "®P o ®P Suburban Railway Section " Also Used By Attiko Metro e AGHIOS HALANDRI l "®P ELEFTHERIOS ALSOS VEIKOU Railway Station a ANTHOUPOLI Galatsi g FILOTHEI AGHIA E KATO PARASKEVI PERISTERI . PATISSIA GALATSI Aghia Peristeri THIMARAKIA P Paraskevi t Haidari Psyhiko "® M AGHIOS NOMISMATOKOPIO AGHIOS Pallini NIKOLAOS ANTONIOS Neo PALLINI Pikermi Psihiko HOLARGOS KYPSELI FAROS SEPOLIA ETHNIKI AGHIA AMYNA P ATTIKI "® MARINA "®P Holargos DIKASTIRIA Aghia PANORMOU ®P ATHENS KATEHAKI Varvara " EGALEO ST.LARISSIS VICTORIA ATHENS ®P AGHIA ALEXANDRAS " VARVARA "®P ELEONAS AMBELOKIPI Papagou Egaleo METAXOURGHIO OMONIA EXARHIA Korydallos Glyka PEANIA-KANTZA AKADEMIA GOUDI Nera PANEPISTIMIO KERAMIKOS "®P MEGARO MONASTIRAKI KOLONAKI MOUSSIKIS KORYDALLOS ZOGRAFOU THISSIO EVANGELISMOS Zografou Nikea ROUF SYNTAGMA ANO ILISSIA Aghios KESSARIANI PAGRATI Ioannis ACROPOLI Rentis PETRALONA NIKEA Tavros Keratsini Kessariani RENTIS SYGROU-FIX P KALITHEA TAVROS "® NEOS VYRONAS MANIATIKA Spata KOSMOS LEFKA Pireaus AGHIOS Vyronas s MOSHATO IOANNIS o Peania Dafni t KAMINIA Moshato Ymittos Kallithea t Drapetsona PIRAEUS DAFNI i FALIRO Nea m o Smyrni Y o Î AGHIOS Ilioupoli DIMOTIKO DIMITRIOS . -

Annual Corporate Social Responsibility Report 2011

ANNUAL CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY REPORT 2011 CONTENTS PART A: THE COMPANY ............................................................................................................... 3 1 CORPORATE PROFILE .......................................................................................................... 3 INTERNATIONAL PRESENCE ..................................................................................................... 6 MILESTONES ..................................................................................................................................... 7 2. CORPORATE GOVERNANCE .......................................................................................... 9 3 MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS ................................................................................................. 12 4 CREDIBILITY ......................................................................................................................... 13 PART B: OPAP S.A. CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY ................................... 16 1 CSR POLICY ........................................................................................................................... 16 2 CSR ACTIONS ...................................................................................................................... 17 5 ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT ............................................................................... 34 6 TRANSPARENCY IN CSR ACTIONS ............................................................................. 37 -

Cultural Heritage in the Realm of the Commons: Conversations on the Case of Greece

Stelios Lekakis Stelios Lekakis Edited by Edited by CulturalCultural heritageheritage waswas inventedinvented inin thethe realmrealm ofof nation-states,nation-states, andand fromfrom EditedEdited byby anan earlyearly pointpoint itit waswas consideredconsidered aa publicpublic good,good, stewardedstewarded toto narratenarrate thethe SteliosStelios LekakisLekakis historichistoric deedsdeeds ofof thethe ancestors,ancestors, onon behalfbehalf ofof theirtheir descendants.descendants. NowaNowa-- days,days, asas thethe neoliberalneoliberal rhetoricrhetoric wouldwould havehave it,it, itit isis forfor thethe benefitbenefit ofof thesethese tax-payingtax-paying citizenscitizens thatthat privatisationprivatisation logiclogic thrivesthrives inin thethe heritageheritage sector,sector, toto covercover theirtheir needsneeds inin thethe namename ofof socialsocial responsibilityresponsibility andand otherother truntrun-- catedcated viewsviews ofof thethe welfarewelfare state.state. WeWe areare nownow atat aa criticalcritical stage,stage, wherewhere thisthis doubledouble enclosureenclosure ofof thethe pastpast endangersendangers monuments,monuments, thinsthins outout theirtheir socialsocial significancesignificance andand manipulatesmanipulates theirtheir valuesvalues inin favourfavour ofof economisticeconomistic horizons.horizons. Conversations on the Case of Greece Conversations on the Case of Greece Cultural Heritage in the Realm of Commons: Cultural Heritage in the Realm of Commons: ThisThis volumevolume examinesexamines whetherwhether wewe cancan placeplace -

Planning Development of Kerameikos up to 35 International Competition 1 Historical and Urban Planning Development of Kerameikos

INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION FOR ARCHITECTS UP TO STUDENT HOUSING 35 HISTORICAL AND URBAN PLANNING DEVELOPMENT OF KERAMEIKOS UP TO 35 INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION 1 HISTORICAL AND URBAN PLANNING DEVELOPMENT OF KERAMEIKOS CONTENTS EARLY ANTIQUITY ......................................................................................................................... p.2-3 CLASSICAL ERA (478-338 BC) .................................................................................................. p.4-5 The municipality of Kerameis POST ANTIQUITY ........................................................................................................................... p.6-7 MIDDLE AGES ................................................................................................................................ p.8-9 RECENT YEARS ........................................................................................................................ p.10-22 A. From the establishment of Athens as capital city of the neo-Greek state until the end of 19th century. I. The first maps of Athens and the urban planning development II. The district of Metaxourgeion • Inclusion of the area in the plan of Kleanthis-Schaubert • The effect of the proposition of Klenze regarding the construction of the palace in Kerameikos • Consequences of the transfer of the palace to Syntagma square • The silk mill factory and the industrialization of the area • The crystallization of the mixed suburban character of the district B. 20th century I. The reformation projects