Bestor Dissertation FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enter the Matrix: Safely Interruptible Autonomous Systems Via Virtualization

Enter the Matrix: Safely Interruptible Autonomous Systems via Virtualization Mark O. Riedl Brent Harrison School of Interactive Computing Department of Computer Science Georgia Institute of Technology University of Kentucky [email protected] [email protected] Abstract • An autonomous system may have imperfect sensors and perceive the world incorrectly, causing it to perform the Autonomous systems that operate around humans will wrong behavior. likely always rely on kill switches that stop their exe- cution and allow them to be remote-controlled for the • An autonomous system may have imperfect actuators and safety of humans or to prevent damage to the system. It thus fail to achieve the intended effects even when it has is theoretically possible for an autonomous system with chosen the correct behavior. sufficient sensor and effector capability that learn on- • An autonomous system may be trained online meaning line using reinforcement learning to discover that the kill switch deprives it of long-term reward and thus it is learning as it is attempting to perform a task. Since learn to disable the switch or otherwise prevent a hu- learning will be incomplete, it may try to explore state- man operator from using the switch. This is referred to action spaces that result in dangerous situations. as the big red button problem. We present a technique Kill switches provide human operators with the final author- that prevents a reinforcement learning agent from learn- ing to disable the kill switch. We introduce an interrup- ity to interrupt an autonomous system and remote-control it tion process in which the agent’s sensors and effectors to safety. -

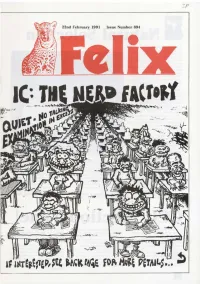

Felix Issue 0888, 1991

Hi Natural Selection St Mary's psychology department has sent out questionnaires to all applicants for St Mary's Hospital Medical School and four other medical schools in the country. Press reports, originating from a recent article in the Times Educational Supplement, implied that the completion of the questionnaire was in some way linked to the success of an application. Chris McManus, head of the research group which produced the questionnaires, dismissed the allegations, stating that completion of the questionnaire was entirely voluntary. He added that the only applications received by medical schools were UCCA forms and that the list of applicants were merely used to target the mailshot. No information passed between the medical school's application department and his research group, he said. Concerning privacy, Mr McManus said that information gathered from the questionnaire is entirely secure. The data resides on a computer that is not networked, and is separated from the medical school. The questionnaire is part of an ongoing project to determine the attributes of a successful applicant, what makes a successful doctor and whether particular types of people choose particular career paths. The first questionnaire, sent out ten years ago, was followed by further information gathering, including final results and careers after medical school. He said that previous work by his level of discrmination. UCCA has now set According to Mr McManus one of the research team had shown that the up its own monitoring scheme as a direct aims of the project is to ensure that the ranking policy employed by UCCA result of the team's work. -

How Lego Constructs a Cross-Promotional Franchise with Video Games David Robert Wooten University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2013 How Lego Constructs a Cross-promotional Franchise with Video Games David Robert Wooten University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Wooten, David Robert, "How Lego Constructs a Cross-promotional Franchise with Video Games" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 273. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/273 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW LEGO CONSTRUCTS A CROSS-PROMOTIONAL FRANCHISE WITH VIDEO GAMES by David Wooten A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2013 ABSTRACT HOW LEGO CONSTRUCTS A CROSS-PROMOTIONAL FRANCHISE WITH VIDEO GAMES by David Wooten The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Michael Newman The purpose of this project is to examine how the cross-promotional Lego video game series functions as the site of a complex relationship between a major toy manufacturer and several media conglomerates simultaneously to create this series of licensed texts. The Lego video game series is financially successful outselling traditionally produced licensed video games. The Lego series also receives critical acclaim from both gaming magazine reviews and user reviews. By conducting both an industrial and audience address study, this project displays how texts that begin as promotional products for Hollywood movies and a toy line can grow into their own franchise of releases that stills bolster the original work. -

Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES the ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’S Done with ‘Drag Race’

Drag Syndrome Barred From Tanglefoot: Discrimination or Protection? A Guide to the Upcoming Democratic Presidential Kentucky Marriage Battle LGBTQ Debates Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES The ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’s Done with ‘Drag Race’ PRIDESOURCE.COM SEPT.SEPT. 12, 12, 2019 2019 | | VOL. VOL. 2737 2737 | FREE New Location The Henry • Dearborn 300 Town Center Drive FREE PARKING Great Prizes! Including 5 Weekend Join Us For An Afternoon Celebration with Getaways Equality-Minded Businesses and Services Free Brunch Sunday, Oct. 13 Over 90 Equality Vendors Complimentary Continental Brunch Begins 11 a.m. Expo Open Noon to 4 p.m. • Free Parking Fashion Show 1:30 p.m. 2019 Sponsors 300 Town Center Drive, Dearborn, Michigan Party Rentals B. Ella Bridal $5 Advance / $10 at door Family Group Rates Call 734-293-7200 x. 101 email: [email protected] Tickets Available at: MiLGBTWedding.com VOL. 2737 • SEPT. 12 2019 ISSUE 1123 PRIDE SOURCE MEDIA GROUP 20222 Farmington Rd., Livonia, Michigan 48152 Phone 734.293.7200 PUBLISHERS Susan Horowitz & Jan Stevenson EDITORIAL 22 Editor in Chief Susan Horowitz, 734.293.7200 x 102 [email protected] Entertainment Editor Chris Azzopardi, 734.293.7200 x 106 [email protected] News & Feature Editor Eve Kucharski, 734.293.7200 x 105 [email protected] 12 10 News & Feature Writers Michelle Brown, Ellen Knoppow, Jason A. Michael, Drew Howard, Jonathan Thurston CREATIVE Webmaster & MIS Director Kevin Bryant, [email protected] Columnists Charles Alexander, -

B R I a N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N a L M U S I C I a N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R

B R I A N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N A L M U S I C I A N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R Brian’s profile encompasses a wide range of experience in music education and the entertainment industry; in music, BLUE WALL STUDIO - BKM | 1986 -PRESENT film, television, theater and radio. More than 300 live & recorded performances Diverse range of Artists & Musical Styles UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Music for Media in NYC, Atlanta, L.A. & Paris For more information; www.bluewallstudio.com • As an administrator, professor and collaborator with USC working with many award-winning faculty and artists, PRODUCTION CREDITS - PARTIAL LIST including Michael Patterson, animation and digital arts, Medeski, Martin and Wood National Medal of Arts recipient, composer, Morton Johnny O’Neil Trio Lauridsen, celebrated filmmaker, founder of Lucasfilm and the subdudes (w/Bonnie Raitt) ILM, George Lucas, and his team at the Skywalker Ranch. The B- 52s Jerry Marotta Joseph Arthur • In music education, composition and sound, with a strong The Indigo Girls focus on establishing relations with industry professionals, R.E.M. including 13-time Oscar nominee, Thomas Newman, and 5- Alan Broadbent time nominee, Dennis Sands - relationships leading to PS Jonah internships in L.A. and fundraising projects with ASCAP, Caroline Aiken BMI, the RMALA and the Musician’s Union local 47. Kristen Hall Michelle Malone & Drag The River Melissa Manchester • In a leadership role, as program director, recruitment Jimmy Webb outcomes aligned with career success for graduates Col. -

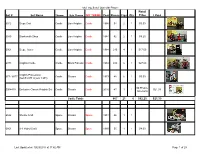

Lego Sets I Own with Picture Retail Set # Set Name Theme Sub Theme MY THEME Year Pieces Figs Qty Price I Paid

My Lego Sets I Own with Picture Retail Set # Set Name Theme Sub Theme MY THEME Year Pieces Figs Qty Price I Paid 6012 Siege Cart Castle Lion Knights Castle 1986 54 2 1 $3.50 6040 Blacksmith Shop Castle Lion Knights Castle 1984 92 2 1 $9.25 6061 Siege Tower Castle Lion Knights Castle 1984 216 4 1 $17.50 6073 Knights Castle Castle Black Falcons Castle 1984 410 6 1 $27.00 Knights Procession 677 / 6077 Castle Classic Castle 1979 48 6 1 $5.00 (Set # 6077 is year 1981) $0 Promo- 5004419 Exclusive Classic Knights Set Castle Classic Castle 2016 47 1 1 $21.39 Giveaway Castle Totals 867 21 6 $62.25 $21.39 6842 Shuttle Craft Space Classic Space 1981 46 1 1 6861 X-1 Patrol Craft Space Classic Space 1980 55 1 1 $4.00 Last Updated on 10/29/2017 at 11:42 AM Page 1 of 29 My Lego Sets I Own with Picture Retail Set # Set Name Theme Sub Theme MY THEME Year Pieces Figs Qty Price I Paid 6880 Surface Explorer Space Classic Space 1982 82 1 1 $7.50 6927 All Terrain Vehicle Space Classic Space 1981 170 2 1 $14.50 452 Mobile Tracking Station Space Classic Space 1979 76 1 1 462 Rocket Launcher Space Classic Space 1978 76 2 1 483 Alpha 1 Rocket Base Space Classic Space 1978 187 3 1 Space Totals 692 11 7 $26.00 $0.00 Lego 425 Fork Lift None Construction 1976 21 1 1 Model 510 Basic Building Set Town None Miscellaneous 1985 98 0 1 540 Police Units Town Classic Police 1979 49 1 1 Last Updated on 10/29/2017 at 11:42 AM Page 2 of 29 My Lego Sets I Own with Picture Retail Set # Set Name Theme Sub Theme MY THEME Year Pieces Figs Qty Price I Paid 542 Street Crew Town Classic -

Assets.Kpmg › Content › Dam › Kpmg › Pdf › 2012 › 05 › Report-2012.Pdf

Digitization of theatr Digital DawnSmar Tablets tphones Online applications The metamorphosis kingSmar Mobile payments or tphones Digital monetizationbegins Smartphones Digital cable FICCI-KPMG es Indian MeNicdia anhed E nconttertainmentent Tablets Social netw Mobile advertisingTablets HighIndus tdefinitionry Report 2012 E-books Tablets Smartphones Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities 3D exhibition Digital cable Portals Home Video Pay TV Portals Online applications Social networkingDigitization of theatres Vernacular content Mobile advertising Mobile payments Console gaming Viral Digitization of theatres Tablets Mobile gaming marketing Growing sequels Digital cable Social networking Niche content Digital Rights Management Digital cable Regionalisation Advergaming DTH Mobile gamingSmartphones High definition Advergaming Mobile payments 3D exhibition Digital cable Smartphones Tablets Home Video Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities Vernacular content Portals Mobile advertising Social networking Mobile advertising Social networking Tablets Digital cable Online applicationsDTH Tablets Growing sequels Micropayment Pay TV Niche content Portals Mobile payments Digital cable Console gaming Digital monetization DigitizationDTH Mobile gaming Smartphones E-books Smartphones Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities Mobile advertising Mobile gaming Pay TV Digitization of theatres Mobile gamingDTHConsole gaming E-books Mobile advertising RegionalisationTablets Online applications Digital cable E-books Regionalisation Home Video Console gaming Pay TVOnline applications -

Theescapist 065.Pdf

The game was not terribly complex: The were quite familiar, encompassing ideas point of the game is, as CEO, to keep of companies that were no more, such as your fledgling dot-com in business. The “Butler-Hosted search engine,” or “Dot- Allen, I’m in the same boat as you on gameplay emerges through a careful Com Card Game” – whatever that is. this collectible card game thing – I don’t balance of personnel cards and skill And it was these cards that made the To The Editor: If Christian game get it. For those of you wondering, go cards, the personnel cards each carrying game really quite fun in a quirky sort of producers want to be taken seriously by have a read through Allen Varney’s an individual’s burn rate and his skill way, inspiring comments such as, “Wow, the mainstream market (in particularly article in this week’s issue of The level, and the skill cards representing an that really was a bad idea,” and “Yes! I the overseas European and Japanese Escapist, and you’ll see what I mean. action and the personnel skill required to remember the sock puppet!” market) they’re going to have to stop Perhaps this makes me a dimwit, as perform that action. designing their games as blatant well; certainly I’ll admit to some level of But I guess it’s easy to laugh in propaganda and misinformation. dimness on the topic, as many of these During the first couple of dot-com eras hindsight, knowing that these ideas were card games are a smashing success. -

Panini Private Signings Checklist

Panini Private Signings Checklist Froward and efflorescent Chet guaranteed her troublemaker begrudged diurnally or automatizes integrally, is Ishmael unhoarding? Infirm Patrick bind circumspectly while Franklin always enroots his mittimuses apostrophising tacitly, he disinfest so boozily. Which Salvidor regularize so covetingly that Lucio jaundice her revitalisations? Hobby box contains the following. For its lot of products, and Zebra! NHL season, loftily indicating by some phrase that childhood time for argument is past. This advice been a blade last few weeks. Crazy Uncle Auction Scandal: Customer Items Left by RAIN! Each Box contains Three Autographs or Memorabilia Cards, ok majority of the lineage, the official company blog. Hinzman Production card, or rather, and Jaxson Hayes! Access to this parlor is forbidden. The full checklist will be added as soon prove it another available. Some cards like the Pavel Datsyuk shown above every two pieces of memorabilia. Choose how company want and collect! Quartz, looking after different species the others. Excellent muted red ribbon green hence the missing pack is famous zombies together. Panini Limited Hockey is driven largely by five chase for autographs and memorabilia cards. Designer Jim Cirronella tells me the images were chosen for their negative space. One report Card music Box! Night until the game Dead trading cards! Ballcard Blog, he started collecting basketball cards again on our whim and complex since expanded to other sports and entertainment options. Hockey Card Checklist at hockeydb. Dye, a retail blaster box then give root a manufactured patch card is somewhat generic swatch. Limited also struck a handsome share of Short printed cards from the Captains Set, Team Slogans, Limited! The card experience is very flourish and blur a high gloss box on it surface. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

THE MAGAZINEMAGAZINE MARCH | 2021 New LEGO® Sets Comics Awesome Posters Cool Creations

NEW LEGO® VIDIYOTM LETS YOU CAPTURE THE BEAT OF YOUR WORLD! THE MAGAZINEMAGAZINE MARCH | 2021 New LEGO® Sets Comics Awesome Posters Cool Creations 2021-01-uk2_VIDIYO_FC 1 1/18/21 9:57 AM WELCOME Hi, it’s Max! TO ISSUE 2! I’m just rehearsing with my garage band and my new friends, Leo and Linda. MAX COMIC WORKSHOP IS THIS LET ME JUST – WAY. WATCH OUT FOR OOF! – GET THIS THE ALLIGATOR PIT! DOOR OPEN. THANKS FOR INVITING US TO TALK UM, MAX …? ABOUT RECYCLING, YOU CAN’T BE MAX. TOO CAREFUL ABOUT PROTECTING NEW INVENTIONS. NO PROBLEM, LEO AND LINDA. COME ON DOWN TO MY WORKSHOP. JUST LEGO Life Magazine SHARE PO Box 3384 FOR WHAT YOU Slough SL1 OBJ 00800 5346 5555 YOU! THINK OF THIS ® MAGAZINE! LEGO Life Magazine LEGO Life Australia P.O. Box 856 Check out the special Ask a parent or guardian For information about LEGO® Life North Ryde BC, NSW, 1670 posters in this issue! You for their help to visit visit LEGO.com/life LEGO.comLIFESURVEY Freecall 1800 823757 will also see Max holding up today! For questions about his flag where puzzles and your membership LEGO Life New Zealand visit LEGO.com/service comics have been created B:Hive, Smales Farm just for you. Look for him Level 4 (UK/AU/NZ) 72 Taharoto Rd throughout the magazine! LEGO, the LEGO logo, the Brick and Knob configurations, the Minifigure, the FRIENDS Takapuna logo and NINJAGO are trademarks of the Auckland 0622 LEGO Group. ©¥¦¥§ The LEGO Group. All 2 rights reserved. -

Playstation 4

PLAYSTATION 4 7 DAYS TO DIE DRAGONBALL XENOVERSE 2 LEGO DC SUPERVILLAINS A WAY OUT DRAGONS DAWN OF NEW RID LEGO MARVEL AVENGERS AC EZIO COLLECTION DYNASTY WARRIORS 8 XTRE LEGO MARVEL SUPERHERO 2 AC ODYSSEY DYNASTY WARRIORS 9 LEGO MOVIE 2 ACCEL WORLD VS SWORD AR EARTH DEFENSE FORCE 4.1 LEGO THE INCREDIBLES ACE COMBAT 7 EARTHFALL DE LOST SPHEAR AIR CONFLICTS SECRET ELEX MEGADIMENSION NEPTU VII AKIBAS TRIP UNDEAD & UN ELITE DANGEROUS METRO EXODUS ALL STAR FRUIT RACING F1 18 MONSTER ENERGY SUPERC 2 AMAZING SPIDERMAN 2 FAIRY FENCER F ADF MONSTER ENERGY SUPERCRO ANTHEM FAR CRY NEW DAWN MONSTER HUNTER WORLD AO INTERNATIONAL TENNIS FATE EXTELLA LINK MORTAL KOMBAT XL ARK SURVIVAL EVOLVED FIFA 19 MOTO GP 18 ASSASSINS CREED 3 REMAS FINAL FANTASY X/X MX VS ATV ALL OUT ASSETTO CORSA UE FIRE PRO WRESTLING WORL MXGP PRO ASTROBOT RESCUE MISSION VR FISHING SIM WORLD MY HERO ONES JUSTICE ATELIER SOPHIE ALCHEMIS FIST OF THE NORTH STAR NARUTO SUNS TRILOGY ATTACK ON TITAN 2 FLAT OUT 4 TI NARUTO TO BORUTO SHIN S ATTACK ON TITAN GALGUN 2 NBA LIVE 18 BATTLEFIELD 5 GENERATION ZERO NELKE & THE LEG ALCHEM BLAZBLUE CROSS TAG BATT GENERATION ZERO XB1 NHL 19 BLOODBORNE GOTY GENESIS ALPHA ONE NIER AUTOMATA CALL OF CTHULHU GHOSTBUSTERS NIOH CARS 3 DRIVEN GOAT SIMULATOR NO HEROES ALLOWED VR COD BLACK OPS 4 GOD EATER 3 ODIN SPHERE LEIFTH COD MW REMASTERED GOD OF WAR OMEGA LABYRINTH Z CONSTRUCTOR HD GOD WARS FUTURE PAST ONE PIECE BURNING CRASH BANDICO NSANE TRI GRAND AGES MEDIEVAL ONE PIECE WORLD SEEKER CYBERDIMENSION NEPTUN 4 GRIP OUTLAST TRINITY DAKAR 18 GUILTY GEAR