Complete Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moma Andy Warhol Motion Pictures

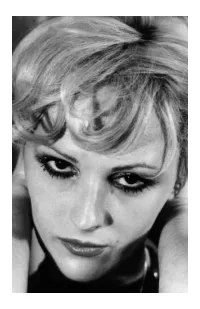

MoMA PRESENTS ANDY WARHOL’S INFLUENTIAL EARLY FILM-BASED WORKS ON A LARGE SCALE IN BOTH A GALLERY AND A CINEMATIC SETTING Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures December 19, 2010–March 21, 2011 The International Council of The Museum of Modern Art Gallery, sixth floor Press Preview: Tuesday, December 14, 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. Remarks at 11:00 a.m. Click here or call (212) 708-9431 to RSVP NEW YORK, December 8, 2010—Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures, on view at MoMA from December 19, 2010, to March 21, 2011, focuses on the artist's cinematic portraits and non- narrative, silent, and black-and-white films from the mid-1960s. Warhol’s Screen Tests reveal his lifelong fascination with the cult of celebrity, comprising a visual almanac of the 1960s downtown avant-garde scene. Included in the exhibition are such Warhol ―Superstars‖ as Edie Sedgwick, Nico, and Baby Jane Holzer; poet Allen Ginsberg; musician Lou Reed; actor Dennis Hopper; author Susan Sontag; and collector Ethel Scull, among others. Other early films included in the exhibition are Sleep (1963), Eat (1963), Blow Job (1963), and Kiss (1963–64). Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures is organized by Klaus Biesenbach, Chief Curator at Large, The Museum of Modern Art, and Director, MoMA PS1. This exhibition is organized in collaboration with The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Twelve Screen Tests in this exhibition are projected on the gallery walls at large scale and within frames, some measuring seven feet high and nearly nine feet wide. An excerpt of Sleep is shown as a large-scale projection at the entrance to the exhibition, with Eat and Blow Job shown on either side of that projection; Kiss is shown at the rear of the gallery in a 50-seat movie theater created for the exhibition; and Sleep and Empire (1964), in their full durations, will be shown in this theater at specially announced times. -

Andy Warhol's

13 MOST BEAUTIFUL... SONGS FOR ANDY WARHOL’S SCREEN TESTS FEAUTURING DEAN & BRITTA JANUARY 17, 2015 OZ ARTS NASHVILLE SUPPORTS THE CREATION, DEVELOPMENT AND PRESENTATION OF SIGNIFICANT CONTEMPORARY PERFORMING AND VISUAL ART WORKS BY LEADING ARTISTS WHOSE CONTRIBUTION INFLUENCES THE ADVANCEMENT OF THEIR FIELD. ADVISORY BOARD Amy Atkinson Karen Elson Jill Robinson Anne Brown Karen Hayes Patterson Sims Libby Callaway Gavin Ivester Mike Smith Chase Cole Keith Meacham Ronnie Steine Jen Cole Ellen Meyer Joseph Sulkowski Stephanie Conner Dave Pittman Stacy Widelitz Gavin Duke Paul Polycarpou Betsy Wills Kristy Edmunds Anne Pope Mel Ziegler aA MESSAGE FROM OZ ARTS President John F. Kennedy had just been assassinated, the Civil Rights Act was mere months from inception, and the US was becoming more heavily involved in the conflict in Vietnam. It was 1964, and at The Factory in New York, Andy Warhol was experimenting with film. Over the course of two years, Andy Warhol selected regulars to his factory, both famous and anonymous that he felt had “star potential” to sit and be filmed in one take, using 100 foot rolls of film. It has been documented that Warhol shot nearly 500 screen tests, but not all were kept. Many of his screen tests have been curated into groups that start with “13 Most Beautiful…” To accompany these film portraits, Dean & Britta, formerly of the NY band, Luna, were commissioned by the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust and The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to create original songs, and remixes of songs from musicians of the era. This endeavor led Dean & Britta to a third studio album consisting of a total of 21 songs titled, “13 Most Beautiful.. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 29, 2019 Curated by Roberta Waddell

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 29, 2019 Curated by Roberta Waddell & Samantha Rippner with Consulting Printer Luther Davis April 4–June 15, 2019 Press Preview, Thursday, April 4, 10–11:30 AM Opening Reception, 6–8 PM, featuring live demonstration by Kayrock Screenprinting _ Charline von Heyl. Untitled, 2007. Screenprint with hand coloring. Sheet: 30 1/8 x 22 1/2 inches. Edition: Unique. Printed by Rob Swainston, Prints of Darkness; published by the artist. Image courtesy the artist and Prints of Darkness. © 2019 Charline von Heyl. Alex Dodge. In the wake of total happiness, 2013. UV screenprint with braille texture on museum board. Sheet: 20 x 32 inches. Edition: 30. Printed by Luther Davis, Axelle Editions; published by Forth Estate Editions. Image courtesy the artist, Forth Estate Editions, and Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery. © 2019 Alex Dodge. Nicole Eisenman. Tea Party, 2012. Lithograph. Sheet: 48 3/4 x 37 1/8 inches. Edition: 25. Printed and published by Andrew Mockler, Jungle Press Editions. Image courtesy the artist and Jungle Press Editions. © 2019 Nicole Eisenman. International Print Center New York is pleased to announce its highly anticipated spring exhibition Pulled In Brooklyn, co-curated by Roberta Waddell and Samantha Rippner, in consultation with printer Luther Davis. This exhibition is the first in-depth exploration of the vibrant network of artists, printers, and workshops that has developed and flourished in Brooklyn since the early 1990s. This monumental exhibition is also IPCNY’s first to occupy two adjacent spaces, -

NO RAMBLING ON: the LISTLESS COWBOYS of HORSE Jon Davies

WARHOL pages_BFI 25/06/2013 10:57 Page 108 If Andy Warhol’s queer cinema of the 1960s allowed for a flourishing of newly articulated sexual and gender possibilities, it also fostered a performative dichotomy: those who command the voice and those who do not. Many of his sound films stage a dynamic of stoicism and loquaciousness that produces a complex and compelling web of power and desire. The artist has summed the binary up succinctly: ‘Talk ers are doing something. Beaut ies are being something’ 1 and, as Viva explained about this tendency in reference to Warhol’s 1968 Lonesome Cowboys : ‘Men seem to have trouble doing these nonscript things. It’s a natural 5_ 10 2 for women and fags – they ramble on. But straight men can’t.’ The brilliant writer and progenitor of the Theatre of the Ridiculous Ronald Tavel’s first two films as scenarist for Warhol are paradigmatic in this regard: Screen Test #1 and Screen Test #2 (both 1965). In Screen Test #1 , the performer, Warhol’s then lover Philip Fagan, is completely closed off to Tavel’s attempts at spurring him to act out and to reveal himself. 3 According to Tavel, he was so up-tight. He just crawled into himself, and the more I asked him, the more up-tight he became and less was recorded on film, and, so, I got more personal about touchy things, which became the principle for me for the next six months. 4 When Tavel turned his self-described ‘sadism’ on a true cinematic superstar, however, in Screen Test #2 , the results were extraordinary. -

New Editions 2012

January – February 2013 Volume 2, Number 5 New Editions 2012: Reviews and Listings of Important Prints and Editions from Around the World • New Section: <100 Faye Hirsch on Nicole Eisenman • Wade Guyton OS at the Whitney • Zarina: Paper Like Skin • Superstorm Sandy • News History. Analysis. Criticism. Reviews. News. Art in Print. In print and online. www.artinprint.org Subscribe to Art in Print. January – February 2013 In This Issue Volume 2, Number 5 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Visibility Associate Publisher New Editions 2012 Index 3 Julie Bernatz Managing Editor Faye Hirsch 4 Annkathrin Murray Nicole Eisenman’s Year of Printing Prodigiously Associate Editor Amelia Ishmael New Editions 2012 Reviews A–Z 10 Design Director <100 42 Skip Langer Design Associate Exhibition Reviews Raymond Hayen Charles Schultz 44 Wade Guyton OS M. Brian Tichenor & Raun Thorp 46 Zarina: Paper Like Skin New Editions Listings 48 News of the Print World 58 Superstorm Sandy 62 Contributors 68 Membership Subscription Form 70 Cover Image: Rirkrit Tiravanija, I Am Busy (2012), 100% cotton towel. Published by WOW (Works on Whatever), New York, NY. Photo: James Ewing, courtesy Art Production Fund. This page: Barbara Takenaga, detail of Day for Night, State I (2012), aquatint, sugar lift, spit bite and white ground with hand coloring by the artist. Printed and published by Wingate Studio, Hinsdale, NH. Art in Print 3500 N. Lake Shore Drive Suite 10A Chicago, IL 60657-1927 www.artinprint.org [email protected] No part of this periodical may be published without the written consent of the publisher. -

Exhibiting Warhols's Screen Tests

1 EXHIBITING WARHOL’S SCREEN TESTS Ian Walker The work of Andy Warhol seems nighwell ubiquitous now, and its continuing relevance and pivotal position in recent culture remains indisputable. Towards the end of 2014, Warhol’s work could be found in two very different shows in Britain. Tate Liverpool staged Transmitting Andy Warhol, which, through a mix of paintings, films, drawings, prints and photographs, sought to explore ‘Warhol’s role in establishing new processes for the dissemination of art’.1 While, at Modern Art Oxford, Jeremy Deller curated the exhibition Love is Enough, bringing together the work of William Morris and Andy Warhol to idiosyncratic but striking effect.2 On a less grand scale was the screening, also at Modern Art Oxford over the week of December 2-7, of a programme of Warhol’s Screen Tests. They were shown in the ‘Project Space’ as part of a programme entitled Straight to Camera: Performance for Film.3 As the title suggests, this featured work by a number of artists in which a performance was directly addressed to the camera and recorded in unrelenting detail. The Screen Tests which Warhol shot in 1964-66 were the earliest works in the programme and stood, as it were, as a starting point for this way of working. Fig 1: Cover of Callie Angell, Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests, 2006 2 How they were made is by now the stuff of legend. A 16mm Bolex camera was set up in a corner of the Factory and the portraits made as the participants dropped by or were invited to sit. -

Research Article

Research Article Embodied Curation: Materials, Performance and the Generation of Knowledge Andy Ditzler* Founder and Curator, Film Love Sydney M. Silverstein Department of Anthropology, Emory University *[email protected] Visual Methodologies: http://journals.sfu.ca/vm/index.php/vm/index Visual Methodologies, Volume 4, Number 1, pp.52-63. Ditzler and Silverstein Research Article The following essay unfolds as a conversation about the staging of a cinematographic tribute to Lou Reed and to the Velvet Underground’s early involvement with Andy Warhol and with underground cinema. The conversation—between the curator-host and an anthropologist-filmmaker present in the audience—pieces together personal registers of the event to make a case for embodied curation—a series of trans-disciplinary and multisensory research and performance practices that are generative of new ways of knowing about, and through, historical materials. Rather than a didactic endeavor, the encounters between curator, materials, and audience members generated new forms of embodied knowledge. Making a case for embodied methods of research and performance, we argue that this generation of knowledge was made possible only through the particular constellation of materials and practices that came together in the staging of this event. Keywords: Andy Warhol, Embodied Curation, Film Projection, Mechanical ABSTRACT Reproduction, Sensory Scholarship, Visual Methodologies. ISSN: 2040-5456 Copyright © 2016 The Research Methods Laboratory. 53 The equipment-free aspect of reality here has become the height of artifice; the sight of immediate reality has become an orchid in the land of technology. -Walter Benjamin “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”(1967: 233) Figure 1: Curator and projections, Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, February 21, 2014. -

Winter 2019.Indd

The Print Club of New York Inc Winter 2019 bership VIP passes to the Art on Paper fair in March. President’s Greeting Details about both the tour to Two Palms and the passes ear Print Club of New York Members, to this fair will be forthcoming. Then the Artists’ Welcome to the second half of the 2018-2019 Showcase will be Monday, May 20th, so put that on your D membership year for the Print Club. I hope every- calendars now if that helps you in your planning. one’s 2019 is off to a good start. We had a wonderful fall Be sure to look for messages in your email inboxes that included some exciting events. As always, our with details about our Club’s upcoming events for 2019. Annual Print artist came to speak to the membership There is much to look forward to! about this year’s print at the National Arts Club. The art- All the best, ist, Amze Emmons, gave us a stellar presentation that pro- Kim Henrikson vided insight into his printmaking practice and influences along with the details about making our Club’s print. I was thrilled to see so many of you in attendance at his talk; I found it illuminating, and he was such a good speaker. If you are looking for more of his work, Amze shows with Dolan/Maxwell in Philadelphia; they always have a booth at the annual IFPDA Fine Art Print Fair with his work on display. Thinking of the Fair, I hope a good number of you took advantage of the Club’s VIP passes and visited again this past fall. -

The Films of Andy Warhol Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things

The Films of Andy Warhol Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things David Gariff National Gallery of Art If you wish for reputation and fame in the world . take every opportunity of advertising yourself. — Oscar Wilde In the future everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes. — attributed to Andy Warhol 1 The Films of Andy Warhol: Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things Andy Warhol’s interest and involvement in film ex- tends back to his childhood days in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Warhol was sickly and frail as a youngster. Illness often kept him bedridden for long periods of time, during which he read movie magazines and followed the lives of Hollywood celebri- ties. He was an avid moviegoer and amassed a large collection of publicity stills of stars given out by local theaters. He also created a movie scrapbook that included a studio portrait of Shirley Temple with the handwritten inscription: “To Andrew Worhola [sic] from Shirley Temple.” By the age of nine, Warhol had received his first camera. Warhol’s interests in cameras, movie projectors, films, the mystery of fame, and the allure of celebrity thus began in his formative years. Many labels attach themselves to Warhol’s work as a filmmaker: documentary, underground, conceptual, experi- mental, improvisational, sexploitation, to name only a few. His film and video output consists of approximately 650 films and 4,000 videos. He made most of his films in the five-year period from 1963 through 1968. These include Sleep (1963), a five- hour-and-twenty-one minute look at a man sleeping; Empire (1964), an eight-hour film of the Empire State Building; Outer and Inner Space (1965), starring Warhol’s muse Edie Sedgwick; and The Chelsea Girls (1966) (codirected by Paul Morrissey), a double-screen film that brought Warhol his greatest com- mercial distribution and success. -

Connolly .Indd

Matt Connolly Solidification and Flux on the “Gay White Way”: Gay Porn Theaters in Post-Stonewall New York City Abstract This paper traces the exhibition strategies of two gay porn theaters in New York City from 1969-1973: the 55th Street Playhouse and the Eros I. It draws upon contemporaneous advertising and trade press to reconstruct these histories, and does so in the pursuit of two interconnected goals. First, by analyzing two venues whose exhibition protocols shifted over the course of this time period, this paper seeks a more nuanced understanding of how gay porn theaters established, maintained, and augmented their market identities. Second, it attempts to use these shifts to consider more broadly what role exhibition practices played in the shaping of gay men’s experiences within the porn theater itself – a key site of spectatorial, erotic, and social engagement. The 1970s saw the proliferation of theaters in major my conclusions in some ways, but that will also urban centers specializing in the exhibition of gay provide the opportunity to investigate exhibition pornography.1 Buoyed by both seismic shifts in spaces within a city that is central to histories of both LGBT visibility in the wake of the 1969 Stonewall LGBT culture and pornographic exhibition.3 I will riots and larger trends in industry, law, and culture track two Manhattan theaters across this time period that increasingly brought pornography of all stripes to observe what films they screened and how they into the mainstream, these theaters provided a public advertised their releases: the 55th Street Playhouse venue for audiences of primarily gay men to view gay and the Eros I. -

A Resource Guide to New York City's Many Cultures

D iv e r C it y : A Resource Guide to New York City’s Many Cultures New York City 2012 DiverCity: A Resource Guide to New York City’s Many Cultures Table of Contents I. Museums and Cultural Institutions A. Art Museums Page 1 B. Historical and Cultural Museums Page 7 C. Landmarks and Memorials Page 12 D. Additional Cultural Institutions Page 15 II. Cultural/Community Organizations and Associations Page 18 III. Performing Arts Centers and Organizations Page 22 IV. College/University Cultural Departments and Potential Speakers Page 25 Mu s eu m s a nd Cu l t u r a l In s ti t u ti o n s “We have become not a melting pot but a beautiful mosaic. Different people, different beliefs, different yearnings, different hopes, different dreams." - Jimmy Carter, 39th President of the United States 1 A) ART MUSEUMS Name Address Phone/ Website Admission Information Description American 2 Lincoln (212) 595-9533 FREE at all times The American Folk Art Museum is the Folk Art Square at leading center for the study and Museum 66th St. Folkartmuseum.org Hours: Tues-Sat enjoyment of American folk art, as well 12:00PM-7:30PM; Sun as the work of international self- taught 12:00PM- 6:00PM artists. Diversity in programming has become a growing emphasis for the museum since the 1990s. Major presentations of African- American and Latino artworks have become a regular feature of the museum's exhibition schedule and permanent collection. Asia Society 725 Park Avenue at (212) 288-6400 FREE Fridays 6-9PM The Asia Society is America's leading 70th Street institution dedicated to fostering Asiasociety.org Price: $10 Adults; $7 understanding of Asia and Seniors; $5 Student ID communication between Americans FREE children under 16 and the peoples of Asia and the Pacific. -

Elizabeth A. Schor Collection, 1909-1995, Undated

Archives & Special Collections UA1983.25, UA1995.20 Elizabeth A. Schor Collection Dates: 1909-1995, Undated Creator: Schor, Elizabeth Extent: 15 linear feet Level of description: Folder Processor & date: Matthew Norgard, June 2017 Administration Information Restrictions: None Copyright: Consult archivist for information Citation: Loyola University Chicago. Archives & Special Collections. Elizabeth A. Schor Collection, 1909-1995, Undated. Box #, Folder #. Provenance: The collection was donated by Elizabeth A. Schor in 1983 and 1995. Separations: None See Also: Melville Steinfels, Martin J. Svaglic, PhD, papers, Carrigan Collection, McEnany collection, Autograph Collection, Kunis Collection, Stagebill Collection, Geary Collection, Anderson Collection, Biographical Sketch Elizabeth A. Schor was a staff member at the Cudahy Library at Loyola University Chicago before retiring. Scope and Content The Elizabeth A. Schor Collection consists of 15 linear feet spanning the years 1909- 1995 and includes playbills, catalogues, newspapers, pamphlets, and an advertisement for a ticket office, art shows, and films. Playbills are from theatres from around the world but the majority of the collection comes from Chicago and New York. Other playbills are from Venice, London, Mexico City and Canada. Languages found in the collection include English, Spanish, and Italian. Series are arranged alphabetically by city and venue. The performances are then arranged within the venues chronologically and finally alphabetically if a venue hosted multiple productions within a given year. Series Series 1: Chicago and Illinois 1909-1995, Undated. Boxes 1-13 This series contains playbills and a theatre guide from musicals, plays and symphony performances from Chicago and other cities in Illinois. Cities include Evanston, Peoria, Lake Forest, Arlington Heights, and Lincolnshire.