Energy Drinks: Exploring Concerns About Marketing to Youth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRAIN on Drugs 101 GATEWAY

BRAIN on DRUGs 101 GATEWAY. TRENDS . Markeng Recognion 2012 1 LT. Ed Moses, Rered 1 Ojecves • Recite number one cancer killer of women {#6 CDC source on slide} • List the three main areas of the brain in order of alcohol impairment {#36 Dr. John Duncan OK U • Idenfy the age of brain maturity {#37 Dr. Daniel Amen of www.amenclinics.com} 2 Target Markeng….Children 3 Our Children Targeted Parents Unaware In the lile world in which children have their existence, whosoever brings them up, there is nothing so finely perceived and so finely felt, as injusce. Charles Dickens 4 More Women Die every year due to Lung Cancer than Breast Cancer *2007 70,880 women died from Lung Cancer, while 40,460 women died from Breast Cancer. *Estimated by American Cancer Society 5 Smoking Rate vs. Cancer Rate About 24yrs #1 7th 6 7 8 Success trends cause Markeng Change Internal Medicine News 11/1/06 Cigaree Nicone Levels Increase 10% in 6 Years . Reports Commissioner Paul J. Cote Jr., of Massachuses Dept. of Public Health one of only 3 states that require tobacco co. to report yearly nicone yields 9 9 ‘07 Camel Ads • Pink Camels for Girls? 10 10 And the latest… VIRGINIA SLIMS “PURSE PACKS” 11 Camel Exoc Blends A few years ago, R.J. Reynolds introduced Camel Exotic Blends in a range of flavors, featuring unusual packaging that was bright and alluring. In 2006, RJR pulled this line of flavored cigarettes after signing a settlement with 39 state AG’s to stop marketing flavored cigarettes. -

Sustainability Report Monster Beverage Corporation

2020 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT MONSTER BEVERAGE CORPORATION FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENT This Report contains forward-looking statements, within the meaning of the U.S. federal securities laws as amended, regarding the expectations of management with respect to our plans, objectives, outlooks, goals, strategies, future operating results and other future events including revenues and profitability. Forward-look- ing statements are generally identified through the inclusion of words such as “aim,” “anticipate,” “believe,” “drive,” “estimate,” “expect,” “goal,” “intend,” “may,” “plan,” “project,” “strategy,” “target,” “hope,” and “will” or similar statements or variations of such terms and other similar expressions. These forward-looking statements are based on management’s current knowledge and expectations and are subject to certain risks and uncertainties, many of which are outside of the control of the Company, that could cause actual results and events to differ materially from the statements made herein. For additional information about the risks, uncer- tainties and other factors that may affect our business, please see our most recent annual report on Form 10-K and any subsequent reports filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, including quarterly reports on Form 10-Q. Monster Beverage Corporation assumes no responsibility to update any forward-looking state- ments whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise. 2020 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT #UNLEASHED TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE CO-CEOS 1 COMPANY AT A GLANCE 3 INTRODUCTION 5 SOCIAL 15 PRODUCT RESPONSIBILITY 37 ENVIRONMENTAL 45 GOVERNANCE 61 CREDITS AND CONTACT 67 INTRODUCTION MONSTER BEVERAGE CORPORATION LETTER FROM THE CO-CEOS As Monster publishes its first Sustainability Report, we cannot ignore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. -

MONITORING FUTURE 2015 Overview

MONITORING the FUTURE NATIONAL SURVEY RESULTS ON DRUG USE 1975–2015 2015 Overview Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use Lloyd D. Johnston Patrick M. O’Malley Richard A. Miech Jerald G. Bachman John E. Schulenberg Sponsored by The National Institute on Drug Abuse at The National Institutes of Health MONITORING THE FUTURE NATIONAL SURVEY RESULTS ON DRUG USE 2015 Overview Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use by Lloyd D. Johnston, Ph.D. Patrick M. O’Malley, Ph.D. Richard A. Miech, Ph.D. Jerald G. Bachman, Ph.D. John E. Schulenberg, Ph.D. The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research Sponsored by: The National Institute on Drug Abuse National Institutes of Health This publication was written by the principal investigators and staff of the Monitoring the Future project at the Institute for Social Research, the University of Michigan, under Research Grant R01 DA 001411 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the sponsor. Public Domain Notice All material appearing in this volume is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied, whether in print or non-print media including derivatives, without permission from the authors. If you plan to modify the material, please contact the Monitoring the Future Project at [email protected] for verification of accuracy. Citation of the source is appreciated, including at least the following: Monitoring the Future, Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Recommended Citation Johnston, L. -

ENERGY DRINK Buyer’S Guide 2007

ENERGY DRINK buyer’s guide 2007 DIGITAL EDITION SPONSORED BY: OZ OZ3UGAR&REE OZ OZ3UGAR&REE ,ITER ,ITER3UGAR&REE -ANUFACTUREDFOR#OTT"EVERAGES53! !$IVISIONOF#OTT"EVERAGES)NC4AMPA &, !FTERSHOCKISATRADEMARKOF#OTT"EVERAGES)NC 777!&4%23(/#+%.%2'9#/- ENERGY DRINK buyer’s guide 2007 OVER 150 BRANDS COMPLETE LISTINGS FOR Introduction ADVERTISING EDITORIAL 1123 Broadway 1 Mifflin Place The BEVNET 2007 Energy Drink Buyer’s Guide is a comprehensive compilation Suite 301 Suite 300 showcasing the energy drink brands currently available for sale in the United States. New York, NY Cambridge, MA While we have added some new tweaks to this year’s edition, the layout is similar to 10010 02138 our 2006 offering, where brands are listed alphabetically. The guide is intended to ph. 212-647-0501 ph. 617-715-9670 give beverage buyers and retailers the ability to navigate through the category and fax 212-647-0565 fax 617-715-9671 make the tough purchasing decisions that they believe will satisfy their customers’ preferences. To that end, we’ve also included updated sales numbers for the past PUBLISHER year indicating overall sales, hot new brands, and fast-moving SKUs. Our “MIA” page Barry J. Nathanson in the back is for those few brands we once knew but have gone missing. We don’t [email protected] know if they’re done for, if they’re lost, or if they just can’t communicate anymore. EDITORIAL DIRECTOR John Craven In 2006, as in 2005, niche-marketed energy brands targeting specific consumer [email protected] interests or demographics continue to expand. All-natural and organic, ethnic, EDITOR urban or hip-hop themed, female- or male-focused, sports-oriented, workout Jeffrey Klineman “fat-burners,” so-called aphrodisiacs and love drinks, as well as those risqué brand [email protected] names aimed to garner notoriety in the media encompass many of the offerings ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER within the guide. -

Patterns of Energy Drink Advertising Over US Television Networks Jennifer A

Research Article Patterns of Energy Drink Advertising Over US Television Networks Jennifer A. Emond, PhD1,2; James D. Sargent, MD1,3; Diane Gilbert-Diamond, ScD1,2 ABSTRACT Objective: To describe programming themes and the inclusion of adolescents in the base audience for television channels with high levels of energy drink advertising airtime. Design: Secondary analysis of energy drink advertising airtime over US network and cable television channels (n ¼ 139) from March, 2012 to February, 2013. Programming themes and the inclusion of adolescents in each channel’s base audience were extracted from cable television trade reports. Main Outcome Measure: Energy drink advertising airtime. Analysis: Channels were ranked by airtime; programming themes and the inclusion of adolescents in the base audience were summarized for the 10 channels with the most airtime. Results: Over the study year, 36,501 minutes (608 hours) were devoted to energy drink advertisements; the top 10 channels accounted for 46.5% of such airtime. Programming themes for the top 10 channels were music (n ¼ 3), sports (n ¼ 3), action-adventure lifestyle (n ¼ 2), African American lifestyle (n ¼ 1), and comedy (n ¼ 1). MTV2 ranked first in airtime devoted to energy drink advertisements. Six of the 10 channels with the most airtime included adolescents aged 12–17 years in their base audience. Conclusions and Implications: Energy drink manufacturers primarily advertise on channels that likely appeal to adolescents. Nutritionists may wish to consider energy drink media literacy when advising adolescents about energy drink consumption. Key Words: energy drinks, adolescents, marketing, television (J Nutr Educ Behav. 2015;47:120-126.) Accepted November 17, 2014. -

Caffeine, Energy Drinks, and Effects on the Body

Caffeine, Energy Drinks, and Effects on the Body Source 1: "Medicines in My Home: Caffeine and Your Body" by the Food and Drug Administration Caffeine Content in Common Drinks and Foods (University of Washington) Item Item size Caffeine (mg) Coffee 150 ml (5 oz) 60–150 Coffee, decaf 150 ml (5 oz) 2–5 Tea 150 ml (5 oz) 40–80 Hot Cocoa 150 ml (5 oz) 1–8 Chocolate Milk 225 ml 2–7 Jolt Cola 12 oz 100 Josta 12 oz 58 Mountain Dew 12 oz 55 Surge 12 oz 51 Diet Coca Cola 12 oz 45 Coca Cola 12 oz 64 Coca Cola Classic 12 oz 23 Dr. Pepper 12 oz 61 Mello Yellow 12 oz 35 Mr. Pibb 12 oz 27 Pepsi Cola 12 oz 43 7-Up 12 oz 0 COPYRIGHT © 2015 by Vantage Learning. All Rights Reserved. No part of this work may be used, accessed, reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means or stored in a database or any retrieval system, without the prior written permission of Vantage Learning. Caffeine, Energy Drinks, and Effects on the Body Mug Root Beer 12 oz 0 Sprite 12 oz 0 Ben & Jerry's No Fat Coffee 1 cup 85 Fudge Frozen Yogurt Starbucks Coffee Ice Cream 1 cup 40–60 Dannon Coffee Yogurt 8 oz 45 100 Grand Bar 1 bar (43 g) 11.2 Krackel Bar 1 bar (47 g) 8.5 Peanut Butter Cup 1 pack (51 g) 5.6 Kit Kat Bar 1 bar (46 g) 5 Raisinets 10 pieces (10 g) 2.5 Butterfinger Bar 1 bar (61 g) 2.4 Baby Ruth Bar 1 bag (60 g) 2.4 Special Dark Chocolate Bar 1 bar (41 g) 31 Chocolate Brownie 1.25 oz 8 Chocolate Chip Cookie 30 g 3–5 Chocolate Ice Cream 50 g 2–5 Milk Chocolate 1 oz 1–15 Bittersweet Chocolate 1 oz 5–35 Source 3: Excerpt from "CAERS Adverse Events Reports Allegedly Related to 5 Hour Energy" by The Food and Drug Administration http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofFoods/CFSAN/CFSANFOIAElectron icReadingRoom/UCM328270.pdf Received Symptoms Outcomes Date ANAPHYLACTIC SHOCK, LIFE THREATENING, VISITED AN ER, URTICARIA, DYSPNOEA, VISITED A HEALTH CARE PROVIDER, 3/24/2011 LETHARGY, HYPERSOMNIA, OTHER SERIOUS (IMPORTANT MEDICAL ASTHENIA EVENTS) RENAL IMPAIRMENT, FOETAL LIFE THREATENING, CONGENITAL 4/21/2011 DISTRESS SYNDROME ANOMALY COPYRIGHT © 2015 by Vantage Learning. -

Update on Emergency Department Visits Involving Energy Drinks: a Continuing Public Health Concern January 10, 2013

January 10, 2013 Update on Emergency Department Visits Involving Energy Drinks: A Continuing Public Health Concern Energy drinks are flavored beverages containing high amounts of caffeine and typically other additives, such as vitamins, taurine, IN BRIEF herbal supplements, creatine, sugars, and guarana, a plant product containing concentrated caffeine. These drinks are sold in cans and X The number of emergency bottles and are readily available in grocery stores, vending machines, department (ED) visits convenience stores, and bars and other venues where alcohol is sold. involving energy drinks These beverages provide high doses of caffeine that stimulate the doubled from 10,068 visits in central nervous system and cardiovascular system. The total amount 2007 to 20,783 visits in 2011 of caffeine in a can or bottle of an energy drink varies from about 80 X Among energy drink-related to more than 500 milligrams (mg), compared with about 100 mg in a 1 ED visits, there were more 5-ounce cup of coffee or 50 mg in a 12-ounce cola. Research suggests male patients than female that certain additives may compound the stimulant effects of caffeine. patients; visits doubled from Some types of energy drinks may also contain alcohol, producing 2007 to 2011 for both male a hazardous combination; however, this report focuses only on the and female patients dangerous effects of energy drinks that do not have alcohol. X In each year from 2007 to Although consumed by a range of age groups, energy drinks were 2011, there were more patients originally marketed -

5-Hour ENERGY® and Caffeine

From: Clark, Charity <[email protected]> Sent: Wednesday, August 14, 2019 2:15 PM To: Iris Lewis <[email protected]> Subject: RE: Five Hour Energy lawsuit Hi, Iris, The original complaint is attached. Thanks, Charity T I STATE OF VERMONT SUPERIOR COURT WASHINGTONUNIT., ,. - I 2 l. ·~ - l I - STATE OF VERMONT, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) CIVIL DIVISON ) Docket No. 4~ "?:> ~J- /Lf ~ftl &) ) LIVING ESSENTIALS, LLC, and ) INNOVATION VENTURES, LLC, ) ) Defendants. ) CONSUMER PROTECTION COMPLAINT Introduction The Vermont Attorney General brings this suit against Living Essentials, LLC and l1U1ovation Ventures, LLC for violations of Vermont's Consumer Protection Act. Defendants have violated the Vermont Consumer Protection Act by making deceptive promotional claims about their 5-hour ENERGY® products, for which the Attorney General seeks civil penalties, injunctive relief, restitution, disgorgement, fees and costs, and other appropriate relief. I. PARTIES, JURISDICTION AND RELATED MATTERS A. Defendants 1. Defendant Living Essentials, LLC ("LE") is a privately-held limited Office of the ATTORNEY GENERAL liability company organized and existing under the laws of the State of Michigan ,,vith 109 State Street Montpelier, VT 05609 its principal place of business at 38955 Hills Tech Dr., Farmington Hills, MI 48331.-LE --markets ·energy-supplements to wholesale dealers and Tetail markets in the United - States. LE manufactured, marketed, distributed, advertised and sold 5-hour ENERGY® at all times relevant hereto. LE is a wholly-owned subsidiary oflnnovation Ventures, LLC. 2. Defendant Innovation Ventures, LLC ("IV") is a privately held limited liability company organized and existing under the laws of the State of Michigan, with its principal place of business at 38955 Hills Tech Dr., Farmington Hills, MI 48331. -

Sports Drinks: the Myths Busted August 5, 2012

Sports drinks: the myths busted August 5, 2012 The Coca-Cola and McDonald's sponsorships for the London Olympics are creating outcry from health advocates, but there's one sponsorship they may be overlooking: Powerade. Powerade, the official drink for athletes at the 2012 Olympic Games (as well as the EUFA 2012), is the sister drink of the other official Olympic drink: Coca-Cola. Is it that surprising? The most common beliefs about sports drinks are that they rehydrate athletes, that all athletes (Olympic or not) can benefit from sports drinks, and that all sports drinks are created equal. Right? Wrong. Reaching for a neon-green Gatorade after your oh-so-grueling spin class may seem like a good idea, but the truth might surprise you. Sports drinks contain electrolytes (mostly potassium and sodium) and sugars to replenish what the body has lost through sweating that water alone can’t replace. The purpose of these beverages is to bring the levels of minerals in your blood closer to their normal levels, so you can continue your workout as if you just started. Sounds great, right? But don’t go reaching for the nearest bottle just yet. Not all sports drinks are created equal, and not every sports drink works the same for every athlete. Most nutritionists agree that sports drinks only become beneficial once your workout extends past 60 minutes. For Olympians, sports drinks might actually do the trick; one study from the University of Bath found that sipping on a carbohydrate-based drink helped athletes’ performances. But that doesn’t mean that drinking water ceases to be essential. -

Mexico Is the Number One Consumer of Coca-Cola in the World, with an Average of 225 Litres Per Person

Arca. Mexico is the number one Company. consumer of Coca-Cola in the On the whole, the CSD industry in world, with an average of 225 litres Mexico has recently become aware per person; a disproportionate of a consolidation process destined number which has surpassed the not to end, characterised by inventors. The consumption in the mergers and acquisitions amongst USA is “only” 200 litres per person. the main bottlers. The producers WATER & CSD This fizzy drink is considered an have widened their product Embotelladoras Arca essential part of the Mexican portfolio by also offering isotonic Coca-Cola Group people’s diet and can be found even drinks, mineral water, juice-based Monterrey, Mexico where there is no drinking water. drinks and products deriving from >> 4 shrinkwrappers Such trend on the Mexican market milk. Coca Cola Femsa, one of the SMI LSK 35 F is also evident in economical terms main subsidiaries of The Coca-Cola >> conveyor belts as it represents about 11% of Company in the world, operates in the global sales of The Coca Cola this context, as well as important 4 installation. local bottlers such as ARCA, CIMSA, BEPENSA and TIJUANA. The Coca-Cola Company These businesses, in addition to distributes 4 out of the the products from Atlanta, also 5 top beverage brands in produce their own label beverages. the world: Coca-Cola, Diet SMI has, to date, supplied the Coke, Sprite and Fanta. Coca Cola Group with about 300 During 2007, the company secondary packaging machines, a worked with over 400 brands and over 2,600 different third of which is installed in the beverages. -

Sheet1 Page 1 Name of Drink Caffeine (Mg) 5 Hour Energy 60

Sheet1 Name of drink Size (mL) Caffeine (mg) 5 Hour Energy 60 Equivalent of a cup of coffee Amp Energy (Original) 710 213 Amp Energy (Original) 473 143 Amp Energy Overdrive 473 142 Amp Energy Re-Ignite 473 158 Amp Energy Traction 473 158 Bawls Guarana 473 103 Bawls Guarana Cherry 473 100 Bawls Guarana G33K B33R 296 80 Bawls Guaranexx Sugar Free 473 103 Beaver Buzz Black Currant Energy 355 188 Beaver Buzz Citrus Energy 355 188 Beaver Buzz Green Machine Energy 473 200 Big Buzz Chronic Energy 473 200 BooKoo Energy Citrus 710 360 BooKoo Energy Wild Berry 710 360 Cheetah Power Surge Diet 710 None? Frank's Energy Drink 500 160 Frank's Energy Drink Lime 250 80 Frank's Energy Drink Pineapple 250 80 Full Throttle Unleaded 473 141 Hansen's Energy Pro 246 39 Hardcore Energize Bullet Blue Rage 85.7 300 Hype Energy Pro (Special Edition) 355 114 Hype Energy MFP 473 151 Inked Chikara 473 151 Inked Maori 473 151 Jolt Endurance Shot 60 200 Jolt Orange Blast 695 220 Lost (Original) 473 160 Lost Five-O 473 160 Mini Thin Rush (6 Hour) 60 200 Monster (Original) 710 246 Monster Assault 473 164 Monster Energy (Original) 473 170 Monster Khaos 710 225 Monster Khaos 473 150 Monster M-80 473 164 Monster MIXXD 473 Monster Reduced Carb 473 140 NOS (Original) 473 200 NOS (Original)(Bottle) 650 343 NOS Fruit Punch 473 246.35 Premium Green Tea Energy 355 119 Premium Iced Tea Energy 355 102 Premium Pink Energy 355 120 Red Bull 250 80 Red Bull 355 113.6 Page 1 Sheet1 Red Rain 250 80 Rocket Shot 54 50 Rockstar Burner 473 160 Rockstar Burner 710 239 Rockstar Diet 473 160 -

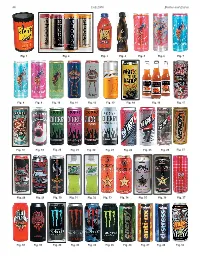

Bottles and Extras Fall 2006 44

44 Fall 2006 Bottles and Extras Fig. 1 Fig. 2 Fig. 3 Fig. 4 Fig. 5 Fig. 6 Fig. 7 Fig. 8 Fig. 9 Fig. 10 Fig. 11 Fig. 12 Fig. 13 Fig. 14 Fig. 16 Fig. 17 Fig. 18 Fig. 19 Fig. 20 Fig. 21 Fig. 22 Fig. 23 Fig. 24 Fig. 25 Fig. 26 Fig. 27 Fig. 28 Fig. 29 Fig. 30 Fig. 31 Fig. 32 Fig. 33 Fig. 34 Fig. 35 Fig. 36 Fig. 37 Fig. 38 Fig. 39 Fig. 40 Fig. 42 Fig. 43 Fig. 45 Fig. 46 Fig. 47 Fig. 48 Fig. 52 Bottles and Extras March-April 2007 45 nationwide distributor of convenience– and dollar-store merchandise. Rosen couldn’t More Energy Drink Containers figure out why Price Master was not selling coffee. “I realized coffee is too much of a & “Extreme Coffee” competitive market,” Rosen said. “I knew we needed a niche.” Rosen said he found Part Two that niche using his past experience of Continued from the Summer 2006 issue selling YJ Stinger (an energy drink) for By Cecil Munsey Price Master. Rosen discovered a company named Copyright © 2006 “Extreme Coffee.” He arranged for Price Master to make an offer and it bought out INTRODUCTION: According to Gary Hemphill, senior vice president of Extreme Coffee. The product was renamed Beverage Marketing Corp., which analyzes the beverage industry, “The Shock and eventually Rosen bought the energy drink category has been growing fairly consistently for a number of brand from Price Master. years. Sales rose 50 percent at the wholesale level, from $653 million in Rosen confidently believes, “We are 2003 to $980 million in 2004 and is still growing.” Collecting the cans and positioned to be the next Red Bull of bottles used to contain these products is paralleling that 50 percent growth coffee!” in sales at the wholesale level.