Tangata Whenua and Mount Aspiring National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DWC Monthly Update

DWC MONTHLY UPDATE SEPTEMBER 2013 Financial Overview DWC’s investments increased in value in July, Total Assets have fallen from $121.5m in which saw the Trust record a surplus of $1.4m for March to $120.5m at 31 July 2013, but net the month. Year to date the trust has a surplus of assets (or equity) have increased from $103.5m $2m against a budget of $1.6m. to $104m. West Coast Construction Excitement building for business awards Alliance formed THE formation of a West Coast Construction needed to advertise. We are still working on Alliance is moving ahead with industry now how a collective will work but we see it as a thinking there may be more opportunities good opportunity for local businesses to see for West Coast businesses outside the how we all operate and potentially we could Christchurch rebuild. pitch for work together,” he says. A second meeting of the Alliance was Mr Conroy says he could see situations where held earlier this month with the group businesses could help each other and this was discussing how the construction, engineering something the Taranaki Alliance seemed to and manufacturing industries can work have done. collectively to maxmise opportunities. The group decided DWC should now obtain The 2012 gala awards night was one to remember. Nelia Heersink from DWC says while it was Taranaki’s code of ethics and adapt them to the initially thought the Alliance could target West Coast situation so they can be discussed he trophies are being designed and An independent judging panel spent three opportunities from the Christchurch rebuild at the next Alliance meeting crafted, evening wear dusted off and weeks going through all the entries before the group also discussed other prospects. -

Greymouth CBD Redevelopment Plan - Greymouth 1 Table of Figures

GREYMOUTH CBD Redevelopment Plan Te Rautaki Whakawhanake a MĀWHERA K. REMETIS - J.LUNDAY - 4SIGHT l 2019 K. REMETIS - J.LUNDAY l DEVELOPMENT PLAN l James Lunday Karen Remetis [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] www.karenremetis.co.nz www.4sight.consulting GREYMOUTH REPORT INFORMATION AND QUALITY CONTROL James Lunday Karen Remetis [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Prepared for : Grey District Council www.karenremetis.co.nz www.4sight.consulting 105 Tainui St Greymouth 7805 Contributor : Benoit Coppens Landscape Architect 4Sight Consulting Author : Zoë Avery Principal Planner, Landscape Architect & Urban Designer 4Sight Consulting Author : James Lunday Principal Reviewer : Renee Davies Principal Landscape Architect 4Sight Consulting Author & Karen Remetis Approved for Director Release: Town Centre Development Group Document Name : Final_CBD_Redevelopment_Plan_v2.0 Version V2.1 July 2019 History: Cover Figure (top) : Lower Tainui Street, Greymouth, 1903 All drawings are preliminary subject to development of design. Photographs included are design precendents Cover Figure (bottom) : Lower Tainui Street, Greymouth, 2019 (photo: Mayor Tony Kokshoorn) only as indicative look and feel for the design. Inside Cover : Greymouth CBD Redevelopment Masterplan CONTENTS l NGĀ KAUPAPA FOREWORD | HE MIHI TAUTOKO 5 HE MIHI TAUTOKO | FOREWORD 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY | TE WHAKARĀPOPOTOTANGA 12 RECOMMENDATIONS | NGĀ KUPU TOHUTOHU 14 1.0 VISION & RATIONALE | HE MOEMOEĀ 17 1.1 UNDERSTANDING THE CONTEXT | HE KUPU WHAKATAKI -

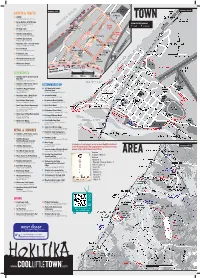

Hokitika Maps

St Mary’s Numbers 32-44 Numbers 1-31 Playground School Oxidation Artists & Crafts Ponds St Mary’s 22 Giſt NZ Public Dumping STAFFORD ST Station 23 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 7448 TOWN Oxidation To Kumara & 2 1 Ponds 48 Gorge Gallery at MZ Design BEACH ST 3 Greymouth 1301 Kaniere Kowhitirangi Rd. TOWN CENTRE PARKING Hokitika Beach Walk Walker (03) 755 7800 Public Dumping PH: HOKITIKA BEACH BEACH ACCESS 4 Health P120 P All Day Park Centre Station 11 Heritage Jade To Kumara & Driſt wood TANCRED ST 86 Revell St. PH: (03) 755 6514 REVELL ST Greymouth Sign 5 Medical 19 Hokitika Craſt Gallery 6 Walker N 25 Tancred St. (03) 755 8802 10 7 Centre PH: 8 11 13 Pioneer Statue Park 6 24 SEWELL ST 13 Hokitika Glass Studio 12 14 WELD ST 16 15 25 Police 9 Weld St. PH: (03) 755 7775 17 Post18 Offi ce Westland District Railway Line 21 Mountain Jade - Tancred Street 9 19 20 Council W E 30 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 8009 22 21 Town Clock 30 SEAVIEW HILL ROAD N 23 26TASMAN SEA 32 16 The Gold Room 28 30 33 HAMILTON ST 27 29 6 37 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 8362 CAMPCarnegie ST Building Swimming Glow-worm FITZHERBERT ST RICHARDS DR kiosk S Pool Dell 31 Traditional Jade Library 34 Historic Lighthouse 2 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 5233 Railway Line BEACH ST REVELL ST 24hr 0 250 m 500 m 20 Westland Greenstone Ltd 31 Seddon SPENCER ST W E 34 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 8713 6 1864 WHARF ST Memorial SEAVIEW HILL ROAD Monument GIBSON QUAY Hokitika 18 Wilderness Gallery Custom House Cemetery 29 Tancred St. -

Review West Coast Regional Coastal

Review of West Coast Region Coastal Hazard Areas Prepared for West Coast Regional Council June 2012 Authors/Contributors: Richard Measures Helen Rouse For any information regarding this report please contact: Helen Rouse Resource Management Consultant +64-3-343 8037 [email protected] National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research Ltd 10 Kyle Street Riccarton Christchurch 8011 PO Box 8602, Riccarton Christchurch 8440 New Zealand Phone +64-3-348 8987 Fax +64-3-348 5548 NIWA Client Report No: CHC2012-081 Report date: June 2012 NIWA Project: ELF12226 © All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced or copied in any form without the permission of the copyright owner(s). Such permission is only to be given in accordance with the terms of the client’s contract with NIWA. This copyright extends to all forms of copying and any storage of material in any kind of information retrieval system. Whilst NIWA has used all reasonable endeavours to ensure that the information contained in this document is accurate, NIWA does not give any express or implied warranty as to the completeness of the information contained herein, or that it will be suitable for any purpose(s) other than those specifically contemplated during the Project or agreed by NIWA and the Client. Contents Executive summary .............................................................................................................. 5 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 6 -

Haast Regional Walks Brochure

Mäori first settled here at least 800 years ago, the sea, Haast Visitor Centre Introduction coast and navigable rivers providing main points of access. Mäori settlement and activity was centred around Information on the Te Wähipounamu - South West New The Haast area is more than a collection of small gathering, carving and trading precious jade, known as Zealand World Heritage Area, other lands administered by settlements near the main highway or along the road to pounamu (greenstone). Jackson Bay Okahu. It is a diverse region, stretching the Department of Conservation, tracks, accommodation European settlement was attempted at Jackson Bay Okahu from Knights Point to the Cascade Valley and inland to the and advice on recreational opportunities in the Haast area during the 1870s. The pioneers’ attempt to “tame” the forest-lined Haast Pass. The area offers a wide variety of can be obtained from the Haast Visitor Centre at Haast landscape was largely unsuccessful but their efforts left scenery, chances to view wildlife and many recreational (situated on the corner of SH6 and the Jackson Bay Road). a tradition of South Westland residents as being tough, opportunities. Hut tickets, hunting permits, maps, conservation souvenirs resilient and independent. and publications can also be obtained from the visitor The region is famous for it’s dramatic coastline - the This brochure should help visitors find their way around the centre. EFTPOS is available. sweeping curves of beaches, the rugged cliff tops, and Haast area. Displays at the Department of Conservation’s the striking rock formations at Knights Point south of Lake Haast Visitor Centre and at other sites within the World Moeraki. -

WEST COAST STATUS REPORT Meeting Paper for West Coast Tai Poutini Conservation Board

WEST COAST STATUS REPORT Meeting Paper For West Coast Tai Poutini Conservation Board TITLE OF PAPER STATUS REPORT AUTHOR: Mark Davies SUBJECT: Status Report for the Board for period ending 15 April 2016 DATE: 21 April 2016 SUMMARY: This report provides information on activities throughout the West Coast since the 19 February 2016 meeting of the West Coast Tai Poutini Conservation Board. MARINE PLACE The Operational Plan for the West Coast Marine Reserves is progressing well. The document will be sent out for Iwi comment on during May. MONITORING The local West Coast monitoring team completed possum monitoring in the Hope and Stafford valleys. The Hope and Stafford valleys are one of the last places possums reached in New Zealand, arriving in the 1990’s. The Hope valley is treated regularly with aerial 1080, the Stafford is not treated. The aim is to keep possum numbers below 5% RTC in the Hope valley and the current monitor found an RTC of 1.3% +/- 1.2%. The Stafford valley is also measured as a non-treatment pair for the Hope valley, it had an RTC of 21.5% +/- 6.2%. Stands of dead tree fuchsia were noted in the Stafford valley, and few mistletoe were spotted. In comparison, the Hope Valley has abundant mistletoe and healthy stands of fuchsia. Mistletoe recruitment plots, FBI and 20x20m plots were measured in the Hope this year, and will be measured in the Stafford valley next year. KARAMEA PLACE Planning Resource Consents received, Regional and District Plans, Management Planning One resource consent was received for in-stream drainage works. -

The Colonial Reinvention of the Hei Tiki: Pounamu, Knowledge and Empire, 1860S-1940S

The Colonial Reinvention of the Hei Tiki: Pounamu, Knowledge and Empire, 1860s-1940s Kathryn Street A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Victoria University of Wellington Te Whare Wānanga o te Ūpoko o te Ika a Māui 2017 Abstract This thesis examines the reinvention of pounamu hei tiki between the 1860s and 1940s. It asks how colonial culture was shaped by engagement with pounamu and its analogous forms greenstone, nephrite, bowenite and jade. The study begins with the exploitation of Ngāi Tahu’s pounamu resource during the West Coast gold rush and concludes with post-World War II measures to prohibit greenstone exports. It establishes that industrially mass-produced pounamu hei tiki were available in New Zealand by 1901 and in Britain by 1903. It sheds new light on the little-known German influence on the commercial greenstone industry. The research demonstrates how Māori leaders maintained a degree of authority in the new Pākehā-dominated industry through patron-client relationships where they exercised creative control. The history also tells a deeper story of the making of colonial culture. The transformation of the greenstone industry created a cultural legacy greater than just the tangible objects of trade. Intangible meanings are also part of the heritage. The acts of making, selling, wearing, admiring, gifting, describing and imagining pieces of greenstone pounamu were expressions of culture in practice. Everyday objects can tell some of these stories and provide accounts of relationships and ways of knowing the world. The pounamu hei tiki speaks to this history because more than merely stone, it is a cultural object and idea. -

Beneath the Reflections

Beneath the Reflections A user’s guide to the Fiordland (Te Moana o Atawhenua) Marine Area Acknowledgements This guide was prepared by the Fiordland Marine Guardians, the Ministry for the Environment, the Ministry for Primary Industries (formerly the Ministry of Fisheries and MAF Biosecurity New Zealand), the Department of Conservation, and Environment Southland. This guide would not have been possible without the assistance of a great many people who provided information, advice and photos. To each and everyone one of you we offer our sincere gratitude. We formally acknowledge Fiordland Cinema for the scenes from the film Ata Whenua and Land Information New Zealand for supplying navigational charts for generating anchorage maps. Cover photo kindly provided by Destination Fiordland. Credit: J. Vale Disclaimer While reasonable endeavours have been made to ensure this information is accurate and up to date, the New Zealand Government makes no warranty, express or implied, nor assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, correctness, completeness or use of any information that is available or referred to in this publication. The contents of this guide should not be construed as authoritative in any way and may be subject to change without notice. Those using the guide should seek specific and up to date information from an authoritative source in relation to: fishing, navigation, moorings, anchorages and radio communications in and around the fiords. Each page in this guide must be read in conjunction with this disclaimer and any other disclaimer that forms part of it. Those who ignore this disclaimer do so at their own risk. -

Overview of the Westland Cultural Heritage Tourism Development Plan 1

Overview of the Westland Cultural Heritage Tourism Development Plan 1. CULTURAL HERITAGE THEMES DEVELOPMENT • Foundation Māori Settlement Heritage Theme – Pounamu: To be developed by Poutini Ngāi Tahu with Te Ara Pounamu Project • Foundation Pākehā Settlement Heritage Theme – West Coast Rain Forest Wilderness Gold Rush • Hokitika - Gold Rush Port, Emporium and Administrative Capital actually on the goldfields • Ross – New Zealand’s most diverse goldfield in terms of types of gold deposits and mining methods • Cultural Themes – Artisans, Food, Products, Recreation derived from untamed, natural wilderness 2. TOWN ENVIRONMENT ENHANCEMENTS 2.1 Hokitika Revitalisation • Cultural Heritage Precincts, Walkways, Interpretation, Public Art and Tohu Whenua Site • Wayfinders and Directional Signs (English, Te Reo Māori, Chinese) 2.2 Ross Enhancement • Enhancement and Experience Plan Development • Wayfinders and Directional Signs (English, Te Reo Māori, Chinese) 3. COMMERCIAL BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT • Go Wild Hokitika and other businesses at TRENZ 2020 • Chinese Visitor Business Cluster • Mahinapua Natural and Cultural Heritage Iconic Attraction 4. COMMUNITY OWNED BUSINESSES AND ACTIVITIES • Westland Industrial Heritage Park Experience Development • Ross Goldfields Heritage Centre and Area Experience Development 5. MARKETING • April 2020 KUMARA JUNCTION to GREYMOUTH Taramakau 73 River Kapitea Creek Overview of the Westland CulturalCHESTERFIELD Heritage 6 KUMARA AWATUNA Londonderry West Coast Rock Tourism Development Plan Wilderness Trail German Gully -

Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence

Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence Editor Dr Richard A Benton Editor: Dr Richard Benton The Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence is published annually by the University of Waikato, Te Piringa – Faculty of Law. Subscription to the Yearbook costs NZ$40 (incl gst) per year in New Zealand and US$45 (including postage) overseas. Advertising space is available at a cost of NZ$200 for a full page and NZ$100 for a half page. Communications should be addressed to: The Editor Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence School of Law The University of Waikato Private Bag 3105 Hamilton 3240 New Zealand North American readers should obtain subscriptions directly from the North American agents: Gaunt Inc Gaunt Building 3011 Gulf Drive Holmes Beach, Florida 34217-2199 Telephone: 941-778-5211, Fax: 941-778-5252, Email: [email protected] This issue may be cited as (2010) Vol 13 Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence. All rights reserved ©. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1994, no part may be reproduced by any process without permission of the publisher. ISSN No. 1174-4243 Yearbook of New ZealaNd JurisprudeNce Volume 13 2010 Contents foreword The Hon Sir Anand Satyanand i preface – of The Hon Justice Sir David Baragwanath v editor’s iNtroductioN ix Dr Alex Frame, Wayne Rumbles and Dr Richard Benton 1 Dr Alex Frame 20 Wayne Rumbles 29 Dr Richard A Benton 38 Professor John Farrar 51 Helen Aikman QC 66 certaiNtY Dr Tamasailau Suaalii-Sauni 70 Dr Claire Slatter 89 Melody Kapilialoha MacKenzie 112 The Hon Justice Sir Edward Taihakurei Durie 152 Robert Joseph 160 a uNitarY state The Hon Justice Paul Heath 194 Dr Grant Young 213 The Hon Deputy Chief Judge Caren Fox 224 Dr Guy Powles 238 Notes oN coNtributors 254 foreword 1 University, Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen, I greet you in the Niuean, Tokelauan and Sign Language. -

PART ONE This Management Plan

F I S H AND GAME NEW ZEALAND WEST COAST REGION SPORTS FISH AND GAME MANAGEMENT PLAN To manage, maintain and enhance the sports fish and game resource in the recreational interests of anglers and hunters AIRPORT DRIVE PO BOX 179 HOKITIKA 1 2 FOREWORD FROM THE CHAIRMAN I am pleased to present the Sportsfish and Game Management Plan for the West Coast Fish and Game Council. This plan has been prepared in line with the statutory responsibilities of Fish and Game West Coast following extensive consultation with a wide range of stakeholders. It identifies issues and establishes goals, objectives, and implementation methods for all output classes. While it provides an excellent snapshot-in-time of Fish and Game West Coast it should be noted that, as well as ongoing issues, there are likely to be further challenges in the future which will have the potential to impact on angler/hunter opportunities and satisfaction. To this extent, this plan must be seen as a document designed to be capable of addressing changing requirements by way of the annual workplan and in response to ongoing input from anglers and hunters, as well as other users of fish and game habitat. The West Coast Fish and Game Council welcomes such input. Andy Harris Chairman 3 SPORTS FISH AND GAME MANAGEMENT PLAN To manage, maintain and enhance the sports fish and game resource in the recreational interests of anglers and hunters CONTENTS Foreword from the chairman ................................................. 3 Contents .................................................................................... 4 Executive summary .................................................................. 5 PART ONE This management plan ............................................................ 6 Introduction .............................................................................. 8 PART TWO Goals and objectives ............................................................ -

He Atua, He Tipua, He Tākata Rānei: an Analysis of Early South Island Māori Oral Traditions

HE ATUA, HE TIPUA, HE TAKATA RĀNEI: THE DYNAMICS OF CHANGE IN SOUTH ISLAND MĀORI ORAL TRADITIONS A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Māori in the University of Canterbury by Eruera Ropata Prendergast-Tarena University of Canterbury 2008 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgments .............................................................................................5 Abstract..............................................................................................................7 Glossary .............................................................................................................8 Technical Notes .................................................................................................9 Part One: The Whakapapa of Literature..........................................................10 Chapter 1......................................................................................................... 11 Introduction......................................................................................................12 Waitaha.........................................................................................................13 Myth and History .........................................................................................14 Authentic Oral Tradition..............................................................................15 Models of Oral Tradition .............................................................................18 The Dynamics