You Cannot Choke Your Boss & (And) Hold Your Job Unless You

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boxed out of The

BOXED OUT OF THE NBA REMEMBERING THE EASTERN PROFESSIONAL BASKETBALL LEAGUE BY SYL SOBEL AND JAY ROSENSTEIN “Syl and Jay brought me back to my brief playing days in the Eastern League! The small towns, the tiny gyms, the rabid fans, the colorful owners, and most of all the seriously good players who played with an edge because they fell one step short of the NBA. All the characters, the stories, and the brutally tough competition – it’s all here. About time the Eastern League got some love!”— Charley Rosen, author, basketball commentator, and former Eastern League player and CBA coach In Boxed out of the NBA: Remembering the Eastern Professional Basketball League, Syl Sobel and Jay Rosenstein tell the fascinating story of a league that was a pro basketball institution for over 30 years, showcasing top players from around the country. During the early years of professional basketball, the Eastern League was the next-best professional league in the world after the NBA. It was home to big-name players such as Sherman White, Jack Molinas, and Bill Spivey, who were implicated in college gambling scandals in the 1950s and were barred from the NBA, and top Black players such as Hal “King” Lear, Julius McCoy, and Wally Choice, who could not make the NBA into the early 1960s due to unwritten team quotas on African-American players. Featuring interviews with some 40 former Eastern League coaches, referees, fans, and players—including Syracuse University coach Jim Boeheim, former Temple University coach John Chaney, former Detroit Pistons player and coach Ray Scott, former NBA coach and ESPN analyst Hubie Brown, and former NBA player and coach Bob Weiss—this book provides an intimate, first-hand account of small-town professional basketball at its best. -

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos + Cards Base Autos Memorabilia Memorabilia Luka Doncic 1112 0 145 630 337 Joe Dumars 1101 0 460 441 200 Grant Hill 1030 0 560 220 250 Nikola Jokic 998 154 420 236 188 Elie Okobo 982 0 140 630 212 Karl-Anthony Towns 980 154 0 752 74 Marvin Bagley III 977 0 10 630 337 Kevin Knox 977 0 10 630 337 Deandre Ayton 977 0 10 630 337 Trae Young 977 0 10 630 337 Collin Sexton 967 0 0 630 337 Anthony Davis 892 154 112 626 0 Damian Lillard 885 154 186 471 74 Dominique Wilkins 856 0 230 550 76 Jaren Jackson Jr. 847 0 5 630 212 Toni Kukoc 847 0 420 235 192 Kyrie Irving 846 154 146 472 74 Jalen Brunson 842 0 0 630 212 Landry Shamet 842 0 0 630 212 Shai Gilgeous- 842 0 0 630 212 Alexander Mikal Bridges 842 0 0 630 212 Wendell Carter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Hamidou Diallo 842 0 0 630 212 Kevin Huerter 842 0 0 630 212 Omari Spellman 842 0 0 630 212 Donte DiVincenzo 842 0 0 630 212 Lonnie Walker IV 842 0 0 630 212 Josh Okogie 842 0 0 630 212 Mo Bamba 842 0 0 630 212 Chandler Hutchison 842 0 0 630 212 Jerome Robinson 842 0 0 630 212 Michael Porter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Troy Brown Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Joel Embiid 826 154 0 596 76 Grayson Allen 826 0 0 614 212 LaMarcus Aldridge 825 154 0 471 200 LeBron James 816 154 0 662 0 Andrew Wiggins 795 154 140 376 125 Giannis 789 154 90 472 73 Antetokounmpo Kevin Durant 784 154 122 478 30 Ben Simmons 781 154 0 627 0 Jason Kidd 776 0 370 330 76 Robert Parish 767 0 140 552 75 Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos -

Downloaded Off Washington on Wednesday

THE TU TS DAILY miereYou Read It First Friday, January 29,1999 Volume XXXVIII, Number 4 1 Dr. King service brings the Endowment fund created in honor of Joseph Gonzalez . Year of Non-violence to end A bly BROOKE MENSCHEL of the First Unitaridn by DANIEL BARBARlSI be marked with a special plaque Daily Editorial Board Universalist Parish in Daily Editorial Board on the inside cover, in memory of The University-wide Year of Cambridge. He is also The memory and legacy of Gonzalez. an active member of Non-vio1ence;which began last Tufts student Joseph Gonzalez, Michael Juliano, one of the National Asso- Martin Luther King Day, ended who passed away suddenly last Gonzalez’ closest friends, de- ciation for the Ad- this Wednesday night with “A year, will be commemorated at scribed the fund as a palpable, vancement of Col- Pilgrimage to Nonviolence,” a Tufts through the creation of an concrete method of preserving ored Persons commemorative service for King. endowment in his honor. The en- Gonzalez’memory. The service, which was held in (NAACP), a visiting dowment, given to the Tisch Li- “Therearea lotofthingsabout lecturer at Harvard’s Goddard Chapel, used King’s own brary for the purpose ofpurchas- Joey you can remember, butthis Divinity school, and words as well as the words of ing additional literature, was ini- book fund is a tangible legacy ... the co-founder and many others to commemorate both tiated through a $10,000 dona- thisone youcan actuallypickup co-director of the theyear and the man. The campus tion by Gonzalez’ parents, Jo- and take in your hand,” Juliano Tuckman Coalition, a chaplains Rev. -

Administration of Barack H. Obama, 2010 Remarks Honoring the 2009 Major League Soccer Champion Real Salt Lake June 4, 2010

Administration of Barack H. Obama, 2010 Remarks Honoring the 2009 Major League Soccer Champion Real Salt Lake June 4, 2010 Hello, everybody. Please have a seat. Well, welcome to the White House. And congratulations on winning your first MLS Cup championship and for bringing the State of Utah its first professional sports title in almost 40 years. That's a pretty big deal. You can give them a round of applause for that again. I want to acknowledge the Senator from the great State of Utah, Senator Bennett, who is here. He is incredibly proud of this team—too tall to play soccer. [Laughter] I want to congratulate Dave Checketts for his leadership and for dedicating his career to expanding the world of professional sports. And, of course, I want to congratulate the players and coaches from Real Salt Lake. I know that this team had a pretty unlikely journey to get here. You qualified for the playoffs on the last day of the season with a losing record. [Laughter] That's cutting it a little close, guys. [Laughter] You beat your biggest rival, took down the defending champions on your way to the title game. And with the cup on the line, you held two of the game's biggest stars scoreless in regulation and went on to win in a shootout, all of which goes to show that in Major League Soccer, there's no such thing as a foregone conclusion. Now, you did it because, in the words of Coach Kreis—and I have to say this is one of the rare coaches that I see in these events who I think might be able to still play—[laughter]—he looks very fit. -

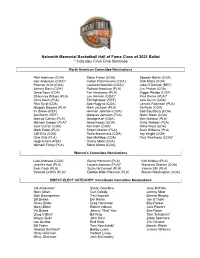

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee North American Committee Nominations Rick Adelman (COA) Steve Fisher (COA) Speedy Morris (COA) Ken Anderson (COA)* Cotton Fitzsimmons (COA) Dick Motta (COA) Fletcher Arritt (COA) Leonard Hamilton (COA)* Jake O’Donnell (REF) Johnny Bach (COA) Richard Hamilton (PLA) Jim Phelan (COA) Gene Bess (COA) Tim Hardaway (PLA) Digger Phelps (COA) Chauncey Billups (PLA) Lou Henson (COA)* Paul Pierce (PLA)* Chris Bosh (PLA) Ed Hightower (REF) Jere Quinn (COA) Rick Byrd (COA) Bob Huggins (COA) Lamont Robinson (PLA) Muggsy Bogues (PLA) Mark Jackson (PLA) Bo Ryan (COA) Irv Brown (REF) Herman Johnson (COA) Bob Saulsbury (COA) Jim Burch (REF) Marques Johnson (PLA) Norm Sloan (COA) Marcus Camby (PLA) George Karl (COA) Ben Wallace (PLA) Michael Cooper (PLA)* Gene Keady (COA) Chris Webber (PLA) Jack Curran (COA) Ken Kern (COA) Willie West (COA) Mark Eaton (PLA) Shawn Marion (PLA) Buck Williams (PLA) Cliff Ellis (COA) Rollie Massimino (COA) Jay Wright (COA) Dale Ellis (PLA) Bob McKillop (COA) Paul Westhead (COA)* Hugh Evans (REF) Danny Miles (COA) Michael Finley (PLA) Steve Moore (COA) Women’s Committee Nominations Leta Andrews (COA) Becky Hammon (PLA) Kim Mulkey (PLA) Jennifer Azzi (PLA) Lauren Jackson (PLA)* Marianne Stanley (COA) Swin Cash (PLA) Suzie McConnell (PLA) Valerie Still (PLA) Yolanda Griffith (PLA)* Debbie Miller-Palmore (PLA) Marian Washington (COA) DIRECT-ELECT CATEGORY: Contributor Committee Nominations Val Ackerman* Simon Gourdine Jerry McHale Marv -

Middle of the Pack Biggest Busts Too Soon to Tell Best

ZSW [C M Y K]CC4 Tuesday, Jun. 23, 2015 ZSW [C M Y K] 4 Tuesday, Jun. 23, 2015 C4 • SPORTS • STAR TRIBUNE • TUESDAY, JUNE 23, 2015 TUESDAY, JUNE 23, 2015 • STAR TRIBUNE • SPORTS • C5 2015 NBA DRAFT HISTORY BEST OF THE REST OF FIRSTS The NBA has held 30 drafts since the lottery began in 1985. With the Wolves slated to pick first for the first time Thursday, staff writer Kent Yo ungblood looks at how well the past 30 N o. 1s fared. Yo u might be surprised how rarely the first player taken turned out to be the best player. MIDDLE OF THE PACK BEST OF ALL 1985 • KNICKS 1987 • SPURS 1992 • MAGIC 1993 • MAGIC 1986 • CAVALIERS 1988 • CLIPPERS 2003 • CAVALIERS Patrick Ewing David Robinson Shaquille O’Neal Chris Webber Brad Daugherty Danny Manning LeBron James Center • Georgetown Center • Navy Center • Louisiana State Forward • Michigan Center • North Carolina Forward • Kansas Forward • St. Vincent-St. Mary Career: Averaged 21.0 points and 9.8 Career: Spurs had to wait two years Career: Sixth all-time in scoring, O’Neal Career: ROY and a five-time All-Star, High School, Akron, Ohio Career: Averaged 19 points and 9 .5 Career: Averaged 14.0 pts and 5.2 rebounds over a 17-year Hall of Fame for Robinson, who came back from woN four titles, was ROY, a 15-time Webber averaged 20.7 points and 9.8 rebounds in eight seasons. A five- rebounds in a career hampered by Career: Rookie of the Year, an All- career. R OY. -

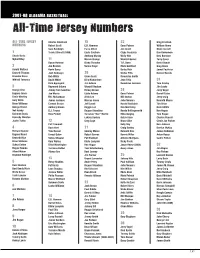

All-Time Jersey Numbers

2007-08 ALABAMA BASKETBALL All-Time Jersey Numbers ALL-TIME JERSEY Charles Cleveland 15 23 Greg Freeman NUMBERS Robert Scott E.B. Hammer Gene Palmer William Henry Sam Randolph Farra Alford Jim Grant Glenn Garrett 1 Travis Stinnett (1999) Eddie Cauthen Clyde Frederick Don Bowerman Chuck Davis Anthony Murray Wally Holt Desi Barmore Mykal Riley 11 Marvin Orange Wendell Garner Terry Coner Dyson Hamner Blake Thrasher T.R. Dunn David Benoit 2 Jim Bratton Verice Cloyd Mark Gottfried Greg Glass Gerald Wallace Kevin Barry Darby Rich Jamal Faulkner Emmett Thomas Jack Kubiszyn 20 Walter Pitts Damon Bacote Brandon Davis Bob White Glenn Scott Demetrius Smith Mikhail Torrance David White Billy Richardson Jean Felix 31 Dick Appleyard Jim Adkins Demetrius Jemison Tom Crosby 3 Raymond Odums Wendell Hudson Jim Lewis George Linn Jimmy Tom Goostree Rickey Brown 24 Jerry Vogel Eugene Jones Joe Morris Eddie Adams Gene Palmer Darrell Estes Ennis Whatley Eric Richardson Alvin Lee Bill Sexton Jerry Craig Gary White James Jackson Marcus Jones John Norman Kenneth Moses Brian Williams Earnest Brown Jeff Lovell Harold Goldstein Tim Orton George Brown Anthony Brown Reggie Lee Ron McKinney David White Neil Ashby D.J. Towns Dejuan Shambley Randy Hollingsworth Ken Hogue Solomon Davis Rico Pickett Terrance “Doc” Martin Mike Quigley Tom Hogue Kennedy Winston LaKory Daniels Butch Dean Charles Russell Justin Tubbs 12 Greg Cage Bruce Albe Clevie Joe Parker Pat Trammell Kelly Shy Ken Johnson 4 Dave Hart 21 Craig Dudley Derrick McKey Richard Gunder Tom Hoover Sammy Moore Kenneth -

The Role Identity Plays in B-Ball Players' and Gangsta Rappers

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2016 Playin’ tha game: the role identity plays in b-ball players’ and gangsta rappers’ public stances on black sociopolitical issues Kelsey Cox Vassar College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Cox, Kelsey, "Playin’ tha game: the role identity plays in b-ball players’ and gangsta rappers’ public stances on black sociopolitical issues" (2016). Senior Capstone Projects. 527. https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone/527 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cox playin’ tha Game: The role identity plays in b-ball players’ and gangsta rappers’ public stances on black sociopolitical issues A Senior thesis by kelsey cox Advised by bill hoynes and Justin patch Vassar College Media Studies April 22, 2016 !1 Cox acknowledgments I would first like to thank my family for helping me through this process. I know it wasn’t easy hearing me complain over school breaks about the amount of work I had to do. Mom – thank you for all of the help and guidance you have provided. There aren’t enough words to express how grateful I am to you for helping me navigate this thesis. Dad – thank you for helping me find my love of basketball, without you I would have never found my passion. Jon – although your constant reminders about my thesis over winter break were annoying you really helped me keep on track, so thank you for that. -

Renormalizing Individual Performance Metrics for Cultural Heritage Management of Sports Records

Renormalizing individual performance metrics for cultural heritage management of sports records Alexander M. Petersen1 and Orion Penner2 1Management of Complex Systems Department, Ernest and Julio Gallo Management Program, School of Engineering, University of California, Merced, CA 95343 2Chair of Innovation and Intellectual Property Policy, College of Management of Technology, Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland. (Dated: April 21, 2020) Individual performance metrics are commonly used to compare players from different eras. However, such cross-era comparison is often biased due to significant changes in success factors underlying player achievement rates (e.g. performance enhancing drugs and modern training regimens). Such historical comparison is more than fodder for casual discussion among sports fans, as it is also an issue of critical importance to the multi- billion dollar professional sport industry and the institutions (e.g. Hall of Fame) charged with preserving sports history and the legacy of outstanding players and achievements. To address this cultural heritage management issue, we report an objective statistical method for renormalizing career achievement metrics, one that is par- ticularly tailored for common seasonal performance metrics, which are often aggregated into summary career metrics – despite the fact that many player careers span different eras. Remarkably, we find that the method applied to comprehensive Major League Baseball and National Basketball Association player data preserves the overall functional form of the distribution of career achievement, both at the season and career level. As such, subsequent re-ranking of the top-50 all-time records in MLB and the NBA using renormalized metrics indicates reordering at the local rank level, as opposed to bulk reordering by era. -

Set Info - Player - 2018-19 Opulence Basketball

Set Info - Player - 2018-19 Opulence Basketball Set Info - Player - 2018-19 Opulence Basketball Player Total # Cards Total # Base Total # Autos Total # Memorabilia Total # Autos + Memorabilia Nikola Jokic 597 58 309 0 230 Deandre Ayton 592 58 295 59 180 Kevin Knox 585 58 295 48 184 Wendell Carter Jr. 585 58 295 46 186 Marvin Bagley III 579 58 295 37 189 Jaren Jackson Jr. 572 58 255 71 188 Trae Young 569 58 295 31 185 Shai Gilgeous-Alexander 564 58 270 39 197 Kyle Kuzma 560 58 308 0 194 Christian Laettner 539 0 309 0 230 Michael Porter Jr. 538 58 270 27 183 Luka Doncic 538 58 295 15 170 Mo Bamba 537 58 270 25 184 Collin Sexton 523 58 255 37 173 De`Aaron Fox 518 58 230 0 230 Grayson Allen 500 0 270 42 188 John Collins 482 58 194 0 230 Kevin Huerter 480 0 270 24 186 Jerome Robinson 478 0 270 24 184 Lonnie Walker IV 473 0 270 21 182 Mikal Bridges 472 0 270 21 181 Donte DiVincenzo 467 0 270 6 191 Landry Shamet 458 0 270 0 188 Troy Brown Jr. 457 0 270 0 187 Josh Okogie 455 0 270 0 185 Jarrett Allen 446 58 158 0 230 Omari Spellman 425 0 270 0 155 Gary Harris 424 0 194 0 230 Robert Parish 424 0 309 0 115 Chris Mullin 423 0 309 0 114 LaMarcus Aldridge 422 58 279 0 85 Lonzo Ball 422 58 279 0 85 Elie Okobo 420 0 270 0 150 Hamidou Diallo 411 0 230 0 181 Kevin Love 404 58 249 12 85 Buddy Hield 403 58 115 0 230 Kyrie Irving 403 58 273 0 72 Khris Middleton 403 58 115 0 230 Zach LaVine 403 58 115 0 230 Jason Kidd 403 0 334 0 69 Anthony Davis 368 58 225 0 85 Allonzo Trier 367 58 270 23 16 Reggie Jackson 365 58 79 0 228 Gordon Hayward 345 0 115 0 230 Kevin -

Professional Sports Leagues and the First Amendment: a Closed Marketplace Christopher J

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 13 Article 5 Issue 2 Spring Professional Sports Leagues and the First Amendment: A Closed Marketplace Christopher J. McKinny Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Christopher J. McKinny, Professional Sports Leagues and the First Amendment: A Closed Marketplace, 13 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 223 (2003) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol13/iss2/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS PROFESSIONAL SPORTS LEAGUES AND THE FIRST AMENDMENT: A CLOSED MARKETPLACE 1. INTRODUCTION: THE CONTROVERSY Get murdered in a second in the first degree Come to me with faggot tendencies You'll be sleeping where the maggots be... Die reaching for heat, leave you leaking in the street Niggers screaming he was a good boy ever since he was born But fluck it he gone Life must go on Niggers don't live that long' Allen Iverson, 2 a.k.a. "Jewelz," 3 from the song "40 Bars." These abrasive lyrics, quoted from Allen Iverson's rap composition "40 Bars," sent a shock-wave of controversy throughout the National Basketball 1. Dave McKenna, Cheap Seats: Bum Rap, WASH. CITY PAPER, July 6-12, 2001, http://www.washingtoncitypaper.com/archives/cheap/2001/cheap0706.html (last visited Jan. 15, 2003). 2. Allen Iverson, a 6-foot, 165-pound shooting guard, currently of the Philadelphia 76ers, was born June 7, 1975 in Hampton, Virginia. -

Download This Issue As A

ROY BRAEGER ‘86 Erica Woda ’04 FORUM: JOHN W. CELEBRATES Tries TO LEVel KLUGE ’37 TELLS GOOD TIMES THE FIELD STORIES TO HIS SON Page 59 Page 22 Page 24 Columbia College September/October 2010 TODAY Student Life A new spirit of community is building on Morningside Heights ’ll meet you for a I drink at the club...” Meet. Dine. Play. Take a seat at the newly renovated bar grill or fine dining room. See how membership in the Columbia Club could fit into your life. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 24 14 68 31 12 22 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS 30 2 S TUDENT LIFE : A NEW B OOK sh E L F LETTER S TO T H E 14 Featured: David Rakoff ’86 EDITOR S PIRIT OF COMMUNITY ON defends pessimism but avoids 3 WIT H IN T H E FA MI L Y M ORNING S IDE HEIG H T S memoirism in his new collec- tion of humorous short stories, 4 AROUND T H E QU A D S Satisfaction with campus life is on the rise, and here Half Empty: WARNING!!! No 4 are some of the reasons why. Inspirational Life Lessons Will Be Homecoming 2010 Found In These Pages. 5 By David McKay Wilson Michael B. Rothfeld ’69 To Receive 32 O BITU A RIE S Hamilton Medal 34 Dr.