Steinhardtite, a New Body-Centered-Cubic Allotropic Form of Aluminum from the Khatyrka CV3 Carbonaceous Chondrite

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big Bang Blunder Bursts the Multiverse Bubble

WORLD VIEW A personal take on events IER P P. PA P. Big Bang blunder bursts the multiverse bubble Premature hype over gravitational waves highlights gaping holes in models for the origins and evolution of the Universe, argues Paul Steinhardt. hen a team of cosmologists announced at a press world will be paying close attention. This time, acceptance will require conference in March that they had detected gravitational measurements over a range of frequencies to discriminate from fore- waves generated in the first instants after the Big Bang, the ground effects, as well as tests to rule out other sources of confusion. And Worigins of the Universe were once again major news. The reported this time, the announcements should be made after submission to jour- discovery created a worldwide sensation in the scientific community, nals and vetting by expert referees. If there must be a press conference, the media and the public at large (see Nature 507, 281–283; 2014). hopefully the scientific community and the media will demand that it According to the team at the BICEP2 South Pole telescope, the is accompanied by a complete set of documents, including details of the detection is at the 5–7 sigma level, so there is less than one chance systematic analysis and sufficient data to enable objective verification. in two million of it being a random occurrence. The results were The BICEP2 incident has also revealed a truth about inflationary the- hailed as proof of the Big Bang inflationary theory and its progeny, ory. The common view is that it is a highly predictive theory. -

Thirty-Fourth List of New Mineral Names

MINERALOGICAL MAGAZINE, DECEMBER 1986, VOL. 50, PP. 741-61 Thirty-fourth list of new mineral names E. E. FEJER Department of Mineralogy, British Museum (Natural History), Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD THE present list contains 181 entries. Of these 148 are Alacranite. V. I. Popova, V. A. Popov, A. Clark, valid species, most of which have been approved by the V. O. Polyakov, and S. E. Borisovskii, 1986. Zap. IMA Commission on New Minerals and Mineral Names, 115, 360. First found at Alacran, Pampa Larga, 17 are misspellings or erroneous transliterations, 9 are Chile by A. H. Clark in 1970 (rejected by IMA names published without IMA approval, 4 are variety because of insufficient data), then in 1980 at the names, 2 are spelling corrections, and one is a name applied to gem material. As in previous lists, contractions caldera of Uzon volcano, Kamchatka, USSR, as are used for the names of frequently cited journals and yellowish orange equant crystals up to 0.5 ram, other publications are abbreviated in italic. sometimes flattened on {100} with {100}, {111}, {ill}, and {110} faces, adamantine to greasy Abhurite. J. J. Matzko, H. T. Evans Jr., M. E. Mrose, lustre, poor {100} cleavage, brittle, H 1 Mono- and P. Aruscavage, 1985. C.M. 23, 233. At a clinic, P2/c, a 9.89(2), b 9.73(2), c 9.13(1) A, depth c.35 m, in an arm of the Red Sea, known as fl 101.84(5) ~ Z = 2; Dobs. 3.43(5), D~alr 3.43; Sharm Abhur, c.30 km north of Jiddah, Saudi reflectances and microhardness given. -

Aperiodic Mineral Structures

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Infoscience - École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne EMU Notes in Mineralogy, Vol. 19 (2017), Chapter 5, 213–254 Aperiodic mineral structures L. BINDI1 and G. CHAPUIS2 1 Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Universita` di Firenze, Via La Pira 4, I-50121 Firenze, Italy 2 Laboratoire de Cristallographie, E´cole Polytechnique Fe´de´rale de Lausanne, CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland The three-dimensional periodic nature of crystalline structures was so strongly anchored in the minds of scientists that the numerous indications that seemed to question this model struggled to acquire the status of validity. The discovery of aperiodic crystals, a generic term including modulated, composite and quasicrystal structures, started in the 1970s with the discovery of incommensurately modulated structures and the presence of satellite reflections surrounding the main reflections in the diffraction patterns. The need to use additional integers to index such diffractograms was soon adopted and theoretical considerations showed that any crystal structure requiring more than three integers to index its diffraction pattern could be described as a periodic object in a higher dimensional space, i.e. superspace, with dimension equal to the number of required integers. The structure observed in physical space is thus a three-dimensional intersection of the structure described as periodic in superspace. Once the symmetry properties of aperiodic crystals were established, the superspace theory was soon adopted in order to describe numerous examples of incommensurate crystal structures from natural and synthetic organic and inorganic compounds even to proteins. Aperiodic crystals thus exhibit perfect atomic structures with long-range order, but without any three-dimensional translational symmetry. -

Previously Unknown Quasicrystal Periodic Approximant Found in Space Received: 13 August 2018 Luca Bindi 1, Joyce Pham 2 & Paul J

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Previously unknown quasicrystal periodic approximant found in space Received: 13 August 2018 Luca Bindi 1, Joyce Pham 2 & Paul J. Steinhardt3,4 Accepted: 16 October 2018 We report the discovery of Al Ni Fe , the frst natural known periodic crystalline approximant Published: xx xx xxxx 34 9 2 to decagonite (Al71Ni24Fe5), a natural quasicrystal composed of a periodic stack of planes with quasiperiodic atomic order and ten-fold symmetry. The new mineral has been approved by the International Mineralogical Association (IMA 2018-038) and ofcially named proxidecagonite, which derives from its identity to periodic approximant of decagonite. Both decagonite and proxidecagonite were found in fragments from the Khatyrka meteorite. Proxidecagonite is the frst natural quasicrystal approximant to be found in the Al-Ni-Fe system. Within this system, the decagonal quasicrystal phase has been reported to transform at ~940 °C to Al13(Fe,Ni)4, Al3(Fe,Ni)2 and the liquid phase, and between 800 and 850 °C to Al13(Fe,Ni)4, Al3(Fe,Ni) and Al3(Fe,Ni)2. The fact that proxidecagonite has not been observed in the laboratory before and formed in a meteorite exposed to high pressures and temperatures during impact-induced shocks suggests that it might be a thermodynamically stable compound at high pressure. The most prominent structural motifs are pseudo-pentagonal symmetry subunits, such as pentagonal bipyramids, that share edges and corners with trigonal bipyramids and which maximize shortest Ni–Al over Ni–Ni contacts. 1,2 Te frst decagonal quasicrystalline (QC) phase found in nature, decagonite Al71Ni24Fe5 , was discovered in the Khatyrka meteorite, a CV3 carbonaceous chondrite3–8. -

Cosmic History and a Candidate Parent Asteroid for the Quasicrystal-Bearing Meteorite Khatyrka

COSMIC HISTORY AND A CANDIDATE PARENT ASTEROID FOR THE QUASICRYSTAL-BEARING METEORITE KHATYRKA Matthias M. M. Meier1*, Luca Bindi2,3, Philipp R. Heck4, April I. Neander5, Nicole H. Spring6,7, My E. I. Riebe1,8, Colin Maden1, Heinrich Baur1, Paul J. Steinhardt9, Rainer Wieler1 and Henner Busemann1 1Institute of Geochemistry and Petrology, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland. 2Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università di Firenze, Florence, Italy. 3CNR-Istituto di Geoscienze e Georisorse, Sezione di Firenze, Florence, Italy. 4Robert A. Pritzker Center for Meteoritics and Polar Studies, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, USA. 5De- partment of Organismal Biology and Anatomy, University of Chicago, Chicago, USA. 6School of Earth and Environ- mental Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK. 7Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Uni- versity of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada. 8Current address: Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, USA. 9Department of Physics, and Princeton Center for Theoretical Science, Princeton University, Princeton, USA. *corresponding author: [email protected]; (office phone: +41 44 632 64 53) Submitted to Earth and Planetary Science Letters. Abstract The unique CV-type meteorite Khatyrka is the only natural sample in which “quasicrystals” and associated crystalline Cu,Al-alloys, including khatyrkite and cupalite, have been found. They are suspected to have formed in the early Solar System. To better understand the origin of these ex- otic phases, and the relationship of Khatyrka to other CV chondrites, we have measured He and Ne in six individual, ~40-μm-sized olivine grains from Khatyrka. We find a cosmic-ray exposure age of about 2-4 Ma (if the meteoroid was <3 m in diameter, more if it was larger). -

EXPERIMENTAL IMPACTS of ALUMINUM PROJECTILES INTO QUARTZ SAND: FORMATION 1,2 1,3 of KHATYRKITE (Cual2) and REDUCTION of QUARTZ to SILICON

Bridging the Gap III (2015) 1071.pdf EXPERIMENTAL IMPACTS OF ALUMINUM PROJECTILES INTO QUARTZ SAND: FORMATION 1,2 1,3 OF KHATYRKITE (CuAl2) AND REDUCTION OF QUARTZ TO SILICON. C. Hamann , D. Stöffler , and W. U. Reimold1,3. 1Museum für Naturkunde, Leibniz-Institut für Evolutions- und Biodiversitätsforschung, In- validenstraße 43, 10115 Berlin, Germany ([email protected]; dieter.stö[email protected]; [email protected]); 2Institut für Geologische Wissenschaften, Freie Universität Berlin, Malteserstraße 74– 100, 12249 Berlin, Germany, 3Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Unter der Linden 6, 10099 Berlin, Germany. Introduction and Rationale: Impact cratering is a melt particles, shock-lithified sand with and without basic geologic process in the solar system, which was distinct shock effects (PDF, diaplectic glass), and frac- predominant over endogenic geologic processes in the tured quartz grains (for details, see the companion early evolution of geologically active planetary bodies. abstract by Wünnemann et al. [10]). Since this study Since most planetary surfaces are highly porous and/or focuses on chemical projectile–target interaction, we composed of non-cohesive materials (e.g., the lunar will only consider impact melt particles that obviously regolith), understanding the influence of pore space show a crust of projectile melt on their top sides. and non-cohesiveness of materials on the impact pro- The bulk compositions of projectile and target were cess is crucial for gaining insights into the evolution of determined with EMPA and XRF, respectively. Impact planetary regoliths. To this end, numerous theoretical melt particles were studied with optical microscopy, and experimental studies have been conducted (e.g., SEM-EDX, and EMPA. -

Design Rules for Discovering 2D Materials from 3D Crystals

Design Rules for Discovering 2D Materials from 3D Crystals by Eleanor Lyons Brightbill Collaborators: Tyler W. Farnsworth, Adam H. Woomer, Patrick C. O'Brien, Kaci L. Kuntz Senior Honors Thesis Chemistry University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill April 7th, 2016 Approved: ___________________________ Dr Scott Warren, Thesis Advisor Dr Wei You, Reader Dr. Todd Austell, Reader Abstract Two-dimensional (2D) materials are championed as potential components for novel technologies due to the extreme change in properties that often accompanies a transition from the bulk to a quantum-confined state. While the incredible properties of existing 2D materials have been investigated for numerous applications, the current library of stable 2D materials is limited to a relatively small number of material systems, and attempts to identify novel 2D materials have found only a small subset of potential 2D material precursors. Here I present a rigorous, yet simple, set of criteria to identify 3D crystals that may be exfoliated into stable 2D sheets and apply these criteria to a database of naturally occurring layered minerals. These design rules harness two fundamental properties of crystals—Mohs hardness and melting point—to enable a rapid and effective approach to identify candidates for exfoliation. It is shown that, in layered systems, Mohs hardness is a predictor of inter-layer (out-of-plane) bond strength while melting point is a measure of intra-layer (in-plane) bond strength. This concept is demonstrated by using liquid exfoliation to produce novel 2D materials from layered minerals that have a Mohs hardness less than 3, with relative success of exfoliation (such as yield and flake size) dependent on melting point. -

![Arxiv:1307.1848V3 [Hep-Th] 8 Nov 2013 Tnadmdla O Nris N H Urn Ig Vacuum Higgs Data](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4366/arxiv-1307-1848v3-hep-th-8-nov-2013-tnadmdla-o-nris-n-h-urn-ig-vacuum-higgs-data-1644366.webp)

Arxiv:1307.1848V3 [Hep-Th] 8 Nov 2013 Tnadmdla O Nris N H Urn Ig Vacuum Higgs Data

Local Conformal Symmetry in Physics and Cosmology Itzhak Bars Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, 90089-0484, USA, Paul Steinhardt Physics Department, Princeton University, Princeton NJ08544, USA, Neil Turok Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, Waterloo, ON N2L 2Y5, Canada. (Dated: July 7, 2013) Abstract We show how to lift a generic non-scale invariant action in Einstein frame into a locally conformally-invariant (or Weyl-invariant) theory and present a new general form for Lagrangians consistent with Weyl symmetry. Advantages of such a conformally invariant formulation of particle physics and gravity include the possibility of constructing geodesically complete cosmologies. We present a conformal-invariant version of the standard model coupled to gravity, and show how Weyl symmetry may be used to obtain unprecedented analytic control over its cosmological solutions. Within this new framework, generic FRW cosmologies are geodesically complete through a series of big crunch - big bang transitions. We discuss a new scenario of cosmic evolution driven by the Higgs field in a “minimal” conformal standard model, in which there is no new physics beyond the arXiv:1307.1848v3 [hep-th] 8 Nov 2013 standard model at low energies, and the current Higgs vacuum is metastable as indicated by the latest LHC data. 1 Contents I. Why Conformal Symmetry? 3 II. Why Local Conformal Symmetry? 8 A. Global scale invariance 8 B. Local scale invariance 11 III. General Weyl Symmetric Theory 15 A. Gravity 15 B. Supergravity 22 IV. Conformal Cosmology 25 Acknowledgments 31 References 31 2 I. WHY CONFORMAL SYMMETRY? Scale invariance is a well-known symmetry [1] that has been studied in many physical contexts. -

Traversing Cosmological Singularities, Complete Journeys Through Spacetime Including Antigravity

Traversing Cosmological Singularities Complete Journeys Through Spacetime Including Antigravity ∗ Itzhak Bars Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089-0484, USA A unique description of the Big Crunch-Big Bang transition is given at the classical gravity level, along with a complete set of homogeneous, isotropic, analytic solutions in scalar-tensor cosmology, with radiation and curvature. All solutions repeat cyclically; they have been obtained by using conformal gauge symmetry (Weyl symmetry) as a powerful tool in cosmology, and more generally in gravity. The significance of the Big Crunch-Big Bang transition is that it provides a model inde- pendent analytic resolution of the singularity, as an unambiguous and unavoidable solution of the equations at the classical gravitational physics level. It is controlled only by geometry (including anisotropy) and only very general features of matter coupled to gravity, such as kinetic energy of a scalar field, and radiation due to all forms of relativistic matter. This analytic resolution of the singularity is due to an attractor mechanism created by the leading terms in the cosmological equa- tion. It is unique, and it is unavoidable in classical relativity in a geodesically complete geometry. Its counterpart in quantum gravity remains to be understood. I. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF RESULTS Resolving the big bang singularity is one of the central challenges for fundamental physics and cosmology. The issue arises naturally in the context of classical relativity due to the geodesically incomplete nature of the singular spacetime [1]-[2]. The resolution may not be completed until the physics is understood in the context of quantum gravity. -

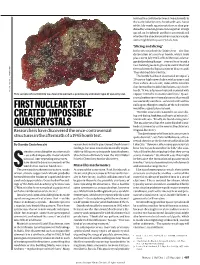

First Nuclear Test Created 'Impossible' Quasicrystals

formed in a collision between two asteroids in the early Solar System, Steinhardt says. Some of the lab-made quasicrystals were also pro- duced by smashing materials together at high speed, so Steinhardt and his team wondered whether the shockwaves from nuclear explo- sions might form quasicrystals, too. ‘Slicing and dicing’ In the aftermath of the Trinity test — the first detonation of a nuclear bomb, which took place on 16 July 1945 at New Mexico’s Alamo- gordo Bombing Range — researchers found a vast field of greenish glassy material that had formed from the liquefaction of desert sand. They dubbed this trinitite. The bomb had been detonated on top of a 30-metre-high tower laden with sensors and their cables. As a result, some of the trinitite that formed had reddish inclusions, says Stein- LUCA BINDI, PAUL J. STEINHARDT BINDI, PAUL LUCA hardt. “It was a fusion of natural material with This sample of red trinitite was found to contain a previously unknown type of quasicrystal. copper from the transmission lines.” Quasi- crystals often form from elements that would not normally combine, so Steinhardt and his colleagues thought samples of the red trinitite FIRST NUCLEAR TEST would be a good place to look. “Over the course of ten months, we were slic- CREATED ‘IMPOSSIBLE’ ing and dicing, looking at all sorts of minerals,” Steinhardt says. “Finally, we found a tiny grain.” QUASICRYSTALS The quasicrystal has the same kind of icosa- hedral symmetry as the one in Shechtman’s Researchers have discovered the once-controversial original discovery. “The dominance of silicon in its structure is structures in the aftermath of a 1945 bomb test. -

Profile of James Peebles, Michel Mayor, and Didier Queloz: 2019 Nobel Laureates in Physics

PROFILE Profile of James Peebles, Michel Mayor, and Didier Queloz: 2019 Nobel Laureates in Physics PROFILE Neta A. Bahcalla,1 and Adam Burrowsa Mankind has long been fascinated by the mysteries of our Universe: How old and how big is the Universe? How did the Universe begin and how is it evolving? What is the composition of the Universe and the nature of its dark matter and dark energy? What is our Earth’s place in the cosmos and are there other planets (and life) around other stars? The 2019 Nobel Prize in Physics honors three pioneering scientists for their fundamental contributions to these cosmic questions—Professors James Peebles of Princeton University, Michel Mayor of the University of Geneva, and Didier Queloz of the University of Geneva and the University of Cambridge—“for contributions (Left) Profs. James Peebles (Princeton University), (Center) Michel Mayor (University of Geneva), and (Right) Didier Queloz (University of Geneva and the University of to our understanding of the evolution of the universe Cambridge). Jessica Gow, Frank Perry, Isabel Infantes/AFP/Scanpix Sweden. and Earth’s place in the cosmos,” with one half to James Peebles “for theoretical discoveries in physical cosmology,” and the other half jointly to Michel Mayor The science of cosmology started in earnest mostly and Didier Queloz “for the discovery of an exoplanet with Einstein’s theory of general relativity. Alexander orbiting a solar-type star.” Friedman, Willem de Sitter, and Georges Lemaître, using Einstein’s equations, recognized that our Universe The Evolution of the Universe is not static, it must be either expanding or contracting James Peebles was born in Southern Manitoba, Can- and Hubble’s remarkable observational discovery of the ada, in 1935; he moved to Princeton University for expanding Universe in 1929 confirmed this. -

Burt Alan Ovrut Curriculum Vitae Personal

BURT ALAN OVRUT CURRICULUM VITAE PERSONAL: Marital Status: Widower Birthplace: New York, NY, USA ADDRESS: Office: University of Pennsylvania Department of Physics Philadelphia, PA 19104 (215) 898-3594 Home: 324 Conshohocken State Road Penn Valley, PA 19072 (215) 668-1890 EDUCATION: Ph.D. - The University of Chicago, June 1978 Thesis - An SP(4) x U(1) Gauge Model of the Weak and Electromagnetic Interactions Thesis Advisors - Professors Benjamin W. Lee and Yoichiro Nambu RESEARCH POSITIONS: July 1990- present Full Professor, Theory Group University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA July 1985 - June 1990 Associate Professor, Theory Group University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA January 1983 - June 1985 Assistant Professor, Theoretical Particle Physics Rockefeller University, New York, NY Sept. 1980 - Dec. 1982 Member, School of Natural Sciences The Institute for Advanced Study Princeton, New Jersey September 1978 - June 1980 Research Associate, High Energy Physics Brandeis University, Boston, Massachusetts VISITING POSITIONS: July 1981 - September 1981 Scientific Associate, Theory Group, CERN Geneva, Switzerland October 1988 - October 1990 Adjunct Professor, Theoretical Particle Physics Rockefeller University, New York, NY October 1992 - October 1993 Scientific Associate, Theory Group, CERN Geneva, Switzerland December 1994- January 1995 Scientific Associate, Theory Group, CERN Geneva, Switzerland September, 1996- May, 1997 Member, School of Natural Sciences The Institute for Advanced Study Princeton, New Jersey September, 1997-August 2001