Reconsidering Mckinney's Cotton Pickers, 1927–34: Performing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JAMU 20160316-1 – DUKE ELLINGTON 2 (Výběr Z Nahrávek)

JAMU 20160316-1 – DUKE ELLINGTON 2 (výběr z nahrávek) C D 2 – 1 9 4 0 – 1 9 6 9 12. Take the ‘A’ Train (Billy Strayhorn) 2:55 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra: Wallace Jones-tp; Ray Nance-tp, vio; Rex Stewart-co; Joe Nanton, Lawrence Brown-tb; Juan Tizol-vtb; Barney Bigard-cl; Johnny Hodges-cl, ss, as; Otto Hardwick-as, bsx; Harry Carney-cl, as, bs; Ben Webster-ts; Billy Strayhorn-p; Fred Guy-g; Jimmy Blanton-b; Sonny Greer-dr. Hollywood, February 15, 1941. Victor 27380/055283-1. CD Giants of Jazz 53046. 11. Pitter Panther Patter (Duke Ellington) 3:01 Duke Ellington-p; Jimmy Blanton-b. Chicago, October 1, 1940. Victor 27221/053504-2. CD Giants of Jazz 53048. 13. I Got It Bad (And That Ain’t Good) (Duke Ellington-Paul Francis Webster) 3:21 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra (same personnel); Ivie Anderson-voc. Hollywood, June 26, 1941. Victor 17531 /061319-1. CD Giants of Jazz 53046. 14. The Star Spangled Banner (Francis Scott Key) 1:16 15. Black [from Black, Brown and Beige] (Duke Ellington) 3:57 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra: Rex Stewart, Harold Baker, Wallace Jones-tp; Ray Nance-tp, vio; Tricky Sam Nanton, Lawrence Brown-tb; Juan Tizol-vtb; Johnny Hodges, Ben Webster, Harry Carney, Otto Hardwicke, Chauncey Haughton-reeds; Duke Ellington-p; Fred Guy-g; Junior Raglin-b; Sonny Greer-dr. Carnegie Hall, NY, January 23, 1943. LP Prestige P 34004/CD Prestige 2PCD-34004-2. Black, Brown and Beige [four selections] (Duke Ellington) 16. Work Song 4:35 17. -

Ellington-Lambert-Richards) 3

1. The Stevedore’s Serenade (Edelstein-Gordon-Ellington) 2. La Dee Doody Doo (Ellington-Lambert-Richards) 3. A Blues Serenade (Parish-Signorelli-Grande-Lytell) 4. Love In Swingtime (Lambert-Richards-Mills) 5. Please Forgive Me (Ellington-Gordon-Mills) 6. Lambeth Walk (Furber-Gay) 7. Prelude To A Kiss (Mills-Gordon-Ellington) 8. Hip Chic (Ellington) 9. Buffet Flat (Ellington) 10. Prelude To A Kiss (Mills-Gordon-Ellington) 11. There’s Something About An Old Love (Mills-Fien-Hudson) 12. The Jeep Is Jumpin’ (Ellington-Hodges) 13. Krum Elbow Blues (Ellington-Hodges) 14. Twits And Twerps (Ellington-Stewart) 15. Mighty Like The Blues (Feather) 16. Jazz Potpourri (Ellington) 17. T. T. On Toast lEllington-Mills) 18. Battle Of Swing (Ellington) 19. Portrait Of The Lion (Ellington) 20. (I Want) Something To Live For (Ellington-Strayhorn) 21. Solid Old Man (Ellington) 22. Cotton Club Stomp (Carney-Hodges-Ellington) 23. Doin’The Voom Voom (Miley-Ellington) 24. Way Low (Ellington) 25. Serenade To Sweden (Ellington) 26. In A Mizz (Johnson-Barnet) 27. I’m Checkin’ Out, Goo’m Bye (Ellington) 28. A Lonely Co-Ed (Ellington) 29. You Can Count On Me (Maxwell-Myrow) 30. Bouncing Buoyancy (Ellington) 31. The Sergeant Was Shy (Ellington) 32. Grievin’ (Strayhorn-Ellington) 33. Little Posey (Ellington) 34. I Never Felt This Way Before (Ellington) 35. Grievin’ (Strayhorn-Ellington) 36. Tootin Through The Roof (Ellington) 37. Weely (A Portrait Of Billy Strayhorn) (Ellington) 38. Killin’ Myself (Ellington) 39. Your Love Has Faded (Ellington) 40. Country Gal (Ellington) 41. Solitude (Ellington-De Lange-Mills) 42. Stormy Weather (Arlen-Köhler) 43. -

Prohibido Full Score

Jazz Lines Publications Presents the jeffrey sultanof master edition prohibido As recorded by benny carter Arranged by benny carter edited by jeffrey sultanof full score from the original manuscript jlp-8230 Music by Benny Carter © 1967 (Renewed 1995) BEE CEE MUSIC CO. All Rights Reserved Including Public Performance for Profit Used by Permission Layout, Design, and Logos © 2010 HERO ENTERPRISES INC. DBA JAZZ LINES PUBLICATIONS AND EJAZZLINES.COM This Arrangement has been Published with the Authorization of the Estate of Benny Carter. Jazz Lines Publications PO Box 1236 Saratoga Springs NY 12866 USA benny carter series prohibido At long last, Benny Carter’s arrangements for saxophone ensembles are now available, authorized by Hilma Carter and the Benny Carter Estate. Carter himself is one of the legendary soloists and composer/arrangers in the history of American music. Born in 1905, he studied piano with his mother, but wanted to play the trumpet. Saving up to buy one, he realized it was a harder instrument that he’d imagined, so he exchanged it for a C-melody saxophone. By the age of fifteen, he was already playing professionally. Carter was already a veteran of such bands as Earl Hines and Charlie Johnson by his twenties. He became chief arranger of the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra when Don Redman left, and brought an entirely new style to the orchestra which was widely imitated by other arrangers and bands. In 1931, he became the musical director of McKinney’s Cotton Pickers, one of the top bands of the era, and once again picked up the trumpet. -

The Solo Style of Jazz Clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 – 1938

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 The solo ts yle of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938 Patricia A. Martin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Patricia A., "The os lo style of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1948. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1948 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SOLO STYLE OF JAZZ CLARINETIST JOHNNY DODDS: 1923 – 1938 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music By Patricia A.Martin B.M., Eastman School of Music, 1984 M.M., Michigan State University, 1990 May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is dedicated to my father and mother for their unfailing love and support. This would not have been possible without my father, a retired dentist and jazz enthusiast, who infected me with his love of the art form and led me to discover some of the great jazz clarinetists. In addition I would like to thank Dr. William Grimes, Dr. Wallace McKenzie, Dr. Willis Delony, Associate Professor Steve Cohen and Dr. -

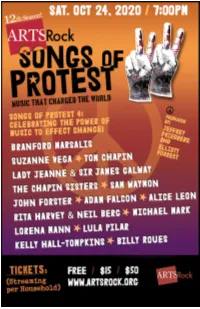

Songs-Of-Protest-2020.Pdf

Elliott Forrest Dara Falco Executive & Artistic Director Managing Director Board of Trustees Stephen Iger, President Melanie Rock, Vice President Joe Morley, Secretary Tim Domini, Treasurer Karen Ayres Rod Greenwood Simon Basner Patrick Heaphy David Brogno James Sarna Hal Coon Lisa Waterworth Jeffrey Doctorow Matthew Watson SUPPORT THE ARTS Donations accepted throughout the show online at ArtsRock.org The mission of ArtsRock is to provide increased access to professional arts and multi-cultural programs for an underserved, diverse audience in and around Rockland County. ArtsRock.org ArtsRock is a 501 (C)(3) Not For-Profit Corporation Dear Friends both Near and Far, Welcome to SONGS OF PROTEST 4, from ArtsRock.org, a non- profit, non-partisan arts organization based in Nyack, NY. We are so glad you have joined us to celebrate the power of music to make social change. Each of the first three SONGS OF PROTEST events, starting in April of 2017, was presented to sold-out audiences in our Rockland, NY community. This latest concert, was supposed to have taken place in-person on April 6th, 2020. We had the performer lineup and songs already chosen when we had to halt the entire season due to the pandemic. As in SONGS OF PROTEST 1, 2 & 3, we had planned to present an evening filled with amazing performers and powerful songs that have had a historical impact on social justice. When we decided to resume the series virtually, we rethought the concept. With so much going on in our country and the world, we offered the performers the opportunity to write or present an original work about an issue from our current state of affairs. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Effort to Reduce Carbon Footprint | Press Releases

PRESS RELEASE Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company Launches Effort to Reduce Carbon Footprint Enabled by Infosys Technologies World’s Largest Manufacturer of Chewing Gum Seeks to Transform Logistics Operations in Western Europe London, UK - November 20, 2008: In a move to extend its social responsibility leadership, the world’s leading manufacturer of chewing gum Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company is reducing the carbon footprint it creates in its logistics operations, Infosys Technologies announced today. Infosys is enabling Wrigley to transform its logistics operations by providing solutions and services in a pilot to determine how much carbon emissions are produced and subsequently may be reduced across the company’s truck-based shipping operations in Western Europe. “Managing our impact on the environment is an integral part of Wrigley corporate philosophy,” said Ian Robertson, head of supply chain sustainability at Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company. “We’re committed to making improvements across all operations but need an integrated enterprise system to measure progress. Infosys provided that solution and services to empower that process.” Early in the pilot, Infosys identified logistics operations in which Wrigley may reduce its carbon footprint by as much as 20 percent, and provided process consulting around operational adoption. The analysis will continue to evaluate Wrigley’s complex distribution network across six countries in Western Europe – spanning more than 44 million kilometers a year in shipments between suppliers, the company and its own customers and includes its distribution centers – for CO2 emissions emitted according to the UK’s Defra (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) standards. Infosys is using its patent-pending Logistics Optimization solution and carbon management tools to deliver the carbon footprint analysis to Wrigley as a managed information service. -

Market Achievements History Product

Wrigley ENG 15.03.2007 12:56 Page 170 Market a confectionery product.These products deliver a Since its founding in 1891,Wrigley has established range of benefits including dental protection itself as a leader in the confectionery industry. It is (Orbit), fresh breath (Winterfresh), enhancing best known for chewing gum and is the world’s memory and improving concentration (Airwaves), largest manufacturer of these products, some of relief of stress, helping in smoking cessation and which are among the best known and loved brands snack avoidance. in the world.Today,Wrigley's brands are woven into Wrigley is one of the pioneers in developing the fabric of everyday life around the world and are the dental benefits of chewing sugarfree gum - sold in over 150 countries.The original brands chewing a sugar-free gum like Orbit reduces the Wrigley’s Spearmint, Doublemint and Juicy Fruit incidence of tooth decay by 40%. Its work and have been joined by the hugely successful brands support in the area of oral healthcare has resulted Orbit,Winterfresh, Airwaves and Hubba Bubba. in dental professionals recommending sugarfree gum Chewing gum consumption in Croatia exceeds to their patients. the amount of 34 million USD and holds 34.8% of the total confectionery market (Nielsen, MAT chewing AM06). In comparison with the past year, the gum companies in the market has witnessed a 3.2% growth, and today, United States, but the industry Wrigley's Orbit is in Croatia a synonym for top was relatively undeveloped. Mr.Wrigley decided that quality chewing gum, holding the leading brand chewing gum was the product with the potential he position in the confectionery category (chocolates had been looking for, so he began marketing it excluded).This product holds 57.4% of the total under his own name. -

¶7櫥«Q }欻' / * #376;扎 #732;†

120825bk Teagarden2 REV 29/3/06 8:46 PM Page 8 Track 14: John Fallstitch, Pokey Carriere, Sid Jack Lantz, trombones; Merton Smith, Vic Rosi, Feller, trumpets; Jack Teagarden, Jose Bob Derry, Bert Noah, Dave Jolley, saxes; Guttierez, Seymour Goldfinger, Joe Ferrall, Norma Teagarden, piano; Charles Gilruth, trombones; Danny Polo, clarinet, alto sax; Tony guitar; Lloyd Springer, bass; Frank Horrington, Antonelli, Joe Ferdinando, alto sax; Art Moore, drums Art Beck, tenor sax; Ernie Hughes, piano; Track 19: Charlie Teagarden, trumpet; Jack Arnold Fishkin, bass; Paul Collins, drums Teagarden, Moe Schneider, trombones; Matty Track 15: John Fallstitch, Pokey Carriere, Matlock, clarinet, tenor sax; Ray Sherman, Truman Quigley, trumpets; Jack Teagarden, piano; Bill Newman, guitar, banjo; Morty Corb, Jose Guttierez, Seymour Goldfinger, Joe Ferrall, bass; Ben Pollack, drums trombones; Danny Polo, clarinet, alto sax; Tony Track 20: Charlie Teagarden, trumpet; Jack Antonelli, Joe Ferdinando, alto sax; Art Moore, Teagarden, trombone; Jay St. John, clarinet; Art Beck, tenor sax; Ernie Hughes, piano; Norma Teagarden, piano; Kass Malone, bass; Arnold Fishkin, bass; Paul Collins, drums Ray Bauduc, drums Track 16: John Fallstitch, Pokey Carriere, Truman Quigley, trumpets; Jack Teagarden, Also available ... Jose Guttierez, Seymour Goldfinger, Joe Ferrall, trombones; Danny Polo, clarinet, alto sax; Tony Antonelli, Joe Ferdinando, alto sax; Art Moore, Art Beck, tenor sax; Ernie Hughes, piano; Perry Botkin, guitar; Arnold Fishkin, bass; Paul Collins, drums Track -

John Cornelius Hodges “Johnny” “Rabbit”

1 The ALTOSAX and SOPRANOSAX of JOHN CORNELIUS HODGES “JOHNNY” “RABBIT” Solographers: Jan Evensmo & Ulf Renberg Last update: Aug. 1, 2014, June 5, 2021 2 Born: Cambridge, Massachusetts, July 25, 1906 Died: NYC. May 11, 1970 Introduction: When I joined the Oslo Jazz Circle back in 1950s, there were in fact only three altosaxophonists who really mattered: Benny Carter, Johnny Hodges and Charlie Parker (in alphabetical order). JH’s playing with Duke Ellington, as well as numerous swing recording sessions made an unforgettable impression on me and my friends. It is time to go through his works and organize a solography! Early history: Played drums and piano, then sax at the age of 14; through his sister, he got to know Sidney Bechet, who gave him lessons. He followed Bechet in Willie ‘The Lion’ Smith’s quartet at the Rhythm Club (ca. 1924), then played with Bechet at the Club Basha (1925). Continued to live in Boston during the mid -1920s, travelling to New York for week-end ‘gigs’. Played with Bobby Sawyer (ca. 1925) and Lloyd Scott (ca. 1926), then from late 1926 worked regularly with Chick webb at Paddock Club, Savoy Ballroom, etc. Briefly with Luckey Roberts’ orchestra, then joined Duke Ellington in May 1928. With Duke until March 1951 when formed own small band (ref. John Chilton). Message: No jazz topic has been studied by more people and more systematically than Duke Ellington. So much has been written, culminating with Luciano Massagli & Giovanni M. Volonte: “The New Desor – An updated edition of Duke Ellington’s Story on Records 1924 – 1974”.