A Historical Review on Panorama Photogrammetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photography and Photomontage in Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment

Photography and Photomontage in Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment Landscape Institute Technical Guidance Note Public ConsuDRAFTltation Draft 2018-06-01 To the recipient of this draft guidance The Landscape Institute is keen to hear the views of LI members and non-members alike. We are happy to receive your comments in any form (eg annotated PDF, email with paragraph references ) via email to [email protected] which will be forwarded to the Chair of the working group. Alternatively, members may make comments on Talking Landscape: Topic “Photography and Photomontage Update”. You may provide any comments you consider would be useful, but may wish to use the following as a guide. 1) Do you expect to be able to use this guidance? If not, why not? 2) Please identify anything you consider to be unclear, or needing further explanation or justification. 3) Please identify anything you disagree with and state why. 4) Could the information be better-organised? If so, how? 5) Are there any important points that should be added? 6) Is there anything in the guidance which is not required? 7) Is there any unnecessary duplication? 8) Any other suggeDRAFTstions? Responses to be returned by 29 June 2018. Incidentally, the ##’s are to aid a final check of cross-references before publication. Contents 1 Introduction Appendices 2 Background Methodology App 01 Site equipment 3 Photography App 02 Camera settings - equipment and approaches needed to capture App 03 Dealing with panoramas suitable images App 04 Technical methodology template -

PANORAMA the Murphy Windmillthe Murphy Etration Restor See Pages 7-9 Pages See

SAN FRANCISCO HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER PANORAMA April-June, 2020 Vol. 32, No. 2 Inside This Issue The Murphy Windmill Restor ation Photo Ron by Henggeler Bret Harte’s Gold Rush See page 3 WPA Murals See page 3 1918 Flu Pandemic See page 11 See pages 7-9 SAN FRANCISCO HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Message from the President COVID-19 debarks from the tongue less trippingly than worked, and what didn’t? On page 11 of mellifluous Spanish Flu, the misnomer for the pandemic that this issue of Panorama, Lorri Ungaretti ravaged the world and San Francisco 102 years ago. But as we’ve gives a summary of how we dealt with read, COVID-19’s arrival here is much like the Spanish flu. the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. COVID-19 too resembles another pandemic, black death, or The San Francisco Historical bubonic plague. Those words conjure the medieval world. Or Society seeks to tell our history, our 17th-century London, where an outbreak killed almost 25% of story (the words have the same root) in the city’s population between 1665 and 1666. At the turn of ways that engage us, entertain us even. the 20th century, twenty years before arrival of the Spanish flu, At the same time we tell our story to the bubonic plague found its way to the United States and San make each of us, as the Romans would Francisco. Here, politicians and power brokers, concerned more say, a better civis, or citizen, and our John Briscoe about commerce than public health, tried to pass off evidence of city, as the Greeks would put it, a President, Board of greater polis, or body of citizens. -

Panorama Photography by Andrew Mcdonald

Panorama Photography by Andrew McDonald Crater Lake - Andrew McDonald (10520 x 3736 - 39.3MP) What is a Panorama? A panorama is any wide-angle view or representation of a physical space, whether in painting, drawing, photography, film/video, or a three-dimensional model. Downtown Kansas City, MO – Andrew McDonald (16614 x 4195 - 69.6MP) How do I make a panorama? Cropping of normal image (4256 x 2832 - 12.0MP) Union Pacific 3985-Andrew McDonald (4256 x 1583 - 6.7MP) • Some Cameras have had this built in • APS Cameras had a setting that would indicate to the printer that the image should be printed as a panorama and would mask the screen off. Some 35mm P&S cameras would show a mask to help with composition. • Advantages • No special equipment or technique required • Best (only?) option for scenes with lots of movement • Disadvantages • Reduction in resolution since you are cutting away portions of the image • Depending on resolution may only be adequate for web or smaller prints How do I make a panorama? Multiple Image Stitching + + = • Digital cameras do this automatically or assist Snake River Overlook – Andrew McDonald (7086 x 2833 - 20.0MP) • Some newer cameras do this by “sweeping the camera” across the scene while holding the shutter button. Images are stitched in-camera. • Other cameras show the left or right edge of prior image to help with composition of next image. Stitching may be done in-camera or multiple images are created. • Advantages • Resolution can be very high by using telephoto lenses to take smaller slices of the scene -

PHOTOGRAMMETRY for FOREST INVENTORY Planning Guidelines

PNC326-1314 Deployment and integration of cost-effective, high spatial resolution, remotely sensed data for the Australian forestry industry PHOTOGRAMMETRY FOR FOREST INVENTORY Planning Guidelines Osborn J.1, Dell M.1, Stone C.2, Iqbal I.1, Lacey M.1, Lucieer A.1, McCoull C.1 1 Discipline of Geography and Spatial Sciences, University of Tasmania 2 Forest Science, NSW Department of Primary Industries Version 1.1: June 2018 Publication: Photogrammetry for Forest Inventory: Planning Guidelines Project Number: PNC326-1314 This work is supported by funding provided to FWPA by the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (DAFF). © 2017 Forest & Wood Products Australia Limited. All rights reserved. Whilst all care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this publication, Forest and Wood Products Australia Limited and all persons associated with them (FWPA) as well as any other contributors make no representations or give any warranty regarding the use, suitability, validity, accuracy, completeness, currency or reliability of the information, including any opinion or advice, contained in this publication. To the maximum extent permitted by law, FWPA disclaims all warranties of any kind, whether express or implied, including but not limited to any warranty that the information is up-to-date, complete, true, legally compliant, accurate, non-misleading or suitable. To the maximum extent permitted by law, FWPA excludes all liability in contract, tort (including negligence), or otherwise for any injury, loss or damage whatsoever (whether direct, indirect, special or consequential) arising out of or in connection with use or reliance on this publication (and any information, opinions or advice therein) and whether caused by any errors, defects, omissions or misrepresentations in this publication. -

John Zjxcaelzel, Zm^Aster Showman of ^Automata and Panoramas

John zJXCaelzel, zM^aster Showman of ^Automata and Panoramas OHN NEPOMUK MAELZEL, the son of an ingenious mechanician and organ builder, was born on August 15, 1772, in Regensburg, J Bavaria. Thoroughly trained in the theory and practice of music, he became the best pianist in Regensburg at the age of fourteen. After teaching music for a few years, he moved to Vienna in 1792, where he occupied himself not only in scientific and mathematical studies, but with mechanical experiments on musical instruments, a field which had become promising after musical clocks were intro- duced in the eighteenth century.1 Maelzel invented an orchestral automaton that was composed of all the pieces of an entire military band and for which Albert, Duke of Saxe-Teschen, paid 3,000 florins in 1803. In 1806 another in- strument of the same kind, with clarinets, violins, violas and violon- cello added, was also completed by Maelzel. This instrument was enclosed in a large cabinet case and played compositions by Mozart, Haydn, Cherubini, Crescentini, and others. It was exhibited with much success locally, and was later taken to Paris where it was christened the "panharmonicon." It received tremendous popularity in Europe, and later toured America where people gladly paid one dollar to hear it perform.2 In 1808 Maelzel produced another invention — an automaton Trumpeter. The Trumpeter was life-size, with lifelike movements, and was dressed in national costumes that could be quickly changed 1 Appletons* Cyclopaedia of American Biography (New York, 1888), IV, 171-172; Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians (New York, 1955), V, 500-501; Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (Leipzig, 1884), XX, 157-158. -

Ground-Based Photographic Monitoring

United States Department of Agriculture Ground-Based Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Photographic General Technical Report PNW-GTR-503 Monitoring May 2001 Frederick C. Hall Author Frederick C. Hall is senior plant ecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region, Natural Resources, P.O. Box 3623, Portland, Oregon 97208-3623. Paper prepared in cooperation with the Pacific Northwest Region. Abstract Hall, Frederick C. 2001 Ground-based photographic monitoring. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-503. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 340 p. Land management professionals (foresters, wildlife biologists, range managers, and land managers such as ranchers and forest land owners) often have need to evaluate their management activities. Photographic monitoring is a fast, simple, and effective way to determine if changes made to an area have been successful. Ground-based photo monitoring means using photographs taken at a specific site to monitor conditions or change. It may be divided into two systems: (1) comparison photos, whereby a photograph is used to compare a known condition with field conditions to estimate some parameter of the field condition; and (2) repeat photo- graphs, whereby several pictures are taken of the same tract of ground over time to detect change. Comparison systems deal with fuel loading, herbage utilization, and public reaction to scenery. Repeat photography is discussed in relation to land- scape, remote, and site-specific systems. Critical attributes of repeat photography are (1) maps to find the sampling location and of the photo monitoring layout; (2) documentation of the monitoring system to include purpose, camera and film, w e a t h e r, season, sampling technique, and equipment; and (3) precise replication of photographs. -

American Scientist the Magazine of Sigma Xi, the Scientific Research Society

A reprint from American Scientist the magazine of Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society This reprint is provided for personal and noncommercial use. For any other use, please send a request to Permissions, American Scientist, P.O. Box 13975, Research Triangle Park, NC, 27709, U.S.A., or by electronic mail to [email protected]. ©Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society and other rightsholders Engineering Next Slide, Please Henry Petroski n the course of preparing lectures years—against strong opposition from Ibased on the material in my books As the Kodak some in the artistic community—that and columns, I developed during the simple projection devices were used by closing decades of the 20th century a the masters to trace in near exactness good-sized library of 35-millimeter Carousel begins its intricate images, including portraits, that slides. These show structures large and the free hand could not do with fidelity. small, ranging from bridges and build- slide into history, ings to pencils and paperclips. As re- The Magic Lantern cently as about five years ago, when I it joins a series of The most immediate antecedent of the indicated to a host that I would need modern slide projector was the magic the use of a projector during a talk, just previous devices used lantern, a device that might be thought about everyone understood that to mean of as a camera obscura in reverse. Instead a Kodak 35-mm slide projector (or its to add images to talks of squeezing a life-size image through a equivalent), and just about every venue pinhole to produce an inverted minia- had one readily available. -

Aerial Aftermathsaerial Aftermaths

AERIAL AFTERMATHSAERIAL AFTERMATHS WARTIME FROM ABOVE WARTIME FROM ABOVE CAREN KAPLAN CAREN KAPLAN AERIAL AFTERMATHS next wave: new directions in women’s studies — Caren Kaplan, Inderpal Grewal, Robyn Wiegman, Series Editors AERIAL AFTERMATHS war time from above CAREN KAPLAN Duke University Press Durham and London 2018 © 2018 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Minion Pro by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Kaplan, Caren, [date–] author. Title: Aerial aftermaths : war time from above / Caren Kaplan. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Series: Next wave | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2017028530 (print) | lccn 2017041830 (ebook) isbn 9780822372219 (ebook) isbn 9780822370086 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822370178 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Photographic surveying— History. | Aerial photography— History. | War photography— History. | Photography, Military. Classification:lcc ta593.2 (ebook) | lcc ta593.2 .k375 2017 (print) | ddc 358.4/54— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2017028530 Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the University of California, Davis, which provided funds to support the publication of this book. Cover art: Grant Heilman Photography Frontispiece: Thomas Baldwin, “The Balloon Prospect from above the Clouds,” in Airopaidia. Hand- colored etching. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. For Sofia — CONTENTS acknowl edgments ix Introduction AERIAL AFTERMATHS 1 1. Surveying War time Aftermaths THE FIRST MILITARY SURVEY OF SCOTLAND 34 2. Balloon Geography THE EMOTION OF MOTION IN AEROSTATIC WARTIME 68 3. La Nature à Coup d’Oeil “SEEING ALL” IN EARLY PA NORAMAS 104 4. -

Digitizing Aerial Photography - Understanding Spatial Resolution

Digitizing Aerial Photography - Understanding Spatial Resolution Trisalyn Nelson Mike Wulder Olaf Niemann M.Sc. Candidate Research Scientist Professor University of Victoria Pacific Forestry Centre University of Victoria (250) 721-7349 (250) 363-6090 (250) 721-7329 email: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Accuracy, flexibility, and cost effectiveness are advantages of using digitized aerial photographs as a data source. However, the relationship between the resolution of digital images, and the aerial photographs from which they were derived, must be addressed. In the following paper we consider issues that impact the spatial resolution of photographs and digitized images, and suggest how users can optimize spatial resolution by selecting an appropriate scanning aperture. Optimal scanning aperture can be chosen by considering the camera system resolution, the original photograph’s scale, and the desired pixel size of the digital image. There are optimal scanning resolutions to use when digitizing aerial photographs. Optimizing spatial resolution will maximize the spatial information obtained from the original photographs without generating unnecessarily large file sizes. Introduction Digitized aerial photography is increasingly the scanning aperture, thereby allowing being used as a data source for studying and important image information to be retained and managing environmental elements such as trees file sizes to be minimized. Choice of scanning (Niemann et al., 1999) and forests (Leckie et al., aperture is related to the resolution of the 1999; Niemann et al., 1999). The popularity of original photograph and/or the desired pixel size digitizing aerial photography is a result of the of the digital image. -

Utilization of Photogrammetry During Establishment of Virtual Rock Collection at Aalto University Jeremiasz Merkel

Utilization of photogrammetry during establishment of virtual rock collection at Aalto University Jeremiasz Merkel School of Engineering Master’s thesis Espoo, 30.09.2019 Supervisor Prof. Jussi Leveinen Advisors M.Sc. Mateusz Janiszewski D.Sc. Lauri Uotinen Aalto University, P.O. BOX 11000, 00076 AALTO www.aalto.fi Abstract of the master’s thesis Author Jeremiasz Merkel Title Utilization of photogrammetry during establishment of virtual rock collection at Aalto University. Master Programme European Mining, Minerals and Environmental Programme. Major European Mining Course Code of major ENG3077 Supervisor Prof. Jussi Leveinen Advisors M.Sc. Mateusz Janiszewski, D.Sc. Lauri Uotinen Date 01.09.2019 Number of pages 56+7 Language English Abstract In recent years, we can observe increasing popularity of the term industry 4.0 which is defined as a new level of organization and control over the entire value chain of the life cycle of products. Experts distinguished nine different technologies, which are essential for the development of industry 4.0. One of them is virtual reality, which is used during processes of data visualisation and digitization. These processes can also include geological collections. Due to limited access to different geological spots, the popularity of destructive techniques during rock testing and high complexity of the process of learning geosciences, geologists are looking for new methods of digitization of different samples of rocks and minerals. The aim of this master thesis was to create a virtual collection of selected rocks and minerals using photogrammetry and virtual reality (VR) technology and develop new tool and interactive learning platform for study mineralogy and petrography. -

The Essential Reference Guide for Filmmakers

THE ESSENTIAL REFERENCE GUIDE FOR FILMMAKERS IDEAS AND TECHNOLOGY IDEAS AND TECHNOLOGY AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ESSENTIAL REFERENCE GUIDE FOR FILMMAKERS Good films—those that e1ectively communicate the desired message—are the result of an almost magical blend of ideas and technological ingredients. And with an understanding of the tools and techniques available to the filmmaker, you can truly realize your vision. The “idea” ingredient is well documented, for beginner and professional alike. Books covering virtually all aspects of the aesthetics and mechanics of filmmaking abound—how to choose an appropriate film style, the importance of sound, how to write an e1ective film script, the basic elements of visual continuity, etc. Although equally important, becoming fluent with the technological aspects of filmmaking can be intimidating. With that in mind, we have produced this book, The Essential Reference Guide for Filmmakers. In it you will find technical information—about light meters, cameras, light, film selection, postproduction, and workflows—in an easy-to-read- and-apply format. Ours is a business that’s more than 100 years old, and from the beginning, Kodak has recognized that cinema is a form of artistic expression. Today’s cinematographers have at their disposal a variety of tools to assist them in manipulating and fine-tuning their images. And with all the changes taking place in film, digital, and hybrid technologies, you are involved with the entertainment industry at one of its most dynamic times. As you enter the exciting world of cinematography, remember that Kodak is an absolute treasure trove of information, and we are here to assist you in your journey. -

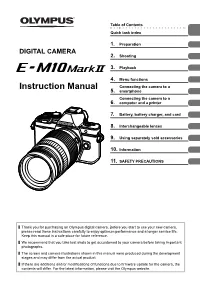

Instruction Manual Connecting the Camera to a 5

Table of Contents Quick task index 1. Preparation DIGITAL CAMERA 2. Shooting 3. Playback 4. Menu functions Instruction Manual Connecting the camera to a 5. smartphone Connecting the camera to a 6. computer and a printer 7. Battery, battery charger, and card 8. Interchangeable lenses 9. Using separately sold accessories 10. Information 11. SAFETY PRECAUTIONS Thank you for purchasing an Olympus digital camera. Before you start to use your new camera, please read these instructions carefully to enjoy optimum performance and a longer service life. Keep this manual in a safe place for future reference. We recommend that you take test shots to get accustomed to your camera before taking important photographs. The screen and camera illustrations shown in this manual were produced during the development stages and may differ from the actual product. If there are additions and/or modifications of functions due to firmware update for the camera, the contents will differ. For the latest information, please visit the Olympus website. Indications used in this manual The following symbols are used throughout this manual. Important information on factors which may lead to a malfunction Cautions or operational problems. Also warns of operations that should be absolutely avoided. $ Notes Points to note when using the camera. Useful information and hints that will help you get the most out of % Tips your camera. g Reference pages describing details or related information. 2 EN Table of Contents Shooting with long exposure time Quick task index 7 of Contents