Chronika Vol6 Full Text.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wxw Holds Keynote on Wxw NOW Streaming

wXw holds keynote on wXw NOW streaming service, announces details on Germany's first wrestling network wXw just announced the first in-depth details on our new "wXw NOW" streaming network, which will launch one month from now on 8/13 at www.wxwnow.de. It will not just be a collection of shows like a lot of companies offer for a monthly fee via Pivotshare but also offer original content and a lot of archived shows, some dating back as far as 2006. We will also have our uniquely designed interface/UI, while hosting and infrastructure will be managed by Vimeo, our long-time streaming partner, dating back to 2013. Wrestling journalist Markus Gronemann (DarkMat.eu, Wrestling Observer) considers this to be the biggest launch of an over-the-top pro wrestling channel by a single promotion since New Japan World. wXw Managing Director Christian Jakobi held a keynote presentation tonight at 8 pm CEST at the wXw Wrestling Academy training school, which was streamed live on Facebook (the video is available, albeit only in German, here) and talked about what future and past events and what kind of original content would be available. We had up to 750 viewers simultaneously on Facebook and also had some students and a trainer (Toby Blunt) in attendance to provide some crowd noise and cheering at key points during the announcement. Marquee Events are wXw's version of pay-per-view caliber shows, where feuds start and end and international talent often appears. There currently are 10 marquee events on the calendar, with some of them being multi-day shows: -

YOUNGS, Sons & CO

v Jmq •« tVr'l'O i vJ: ~Mv <<•'- ;Pn;:o'-t: ;'n; PUBLISHED E1EEY TUESDAY MORNING BY A. H. BYINGTON, AT TWO DOLLARS PER ANNUM, IN AD VANCE v; i- .-t •;v r:-vnj; r-,v; .?? J oJq:jj< a iiraiiltj IgEmopaper—Ktttateit ia JCtrcal Mm anil Mrtsto, <®mral Sofelligenct, Xitetattire, ^gricnlhtrt, ^ttjromnf, tjit Sitfe, finlH & in 1800. : • J! IL OV: NUMBER 495-M1W SERIES. NORWALK, CONN., TUESDAY, JUNE 30, 1857. VOLUME XL.—NUMBER 26. New Coal Yard. Norwalk Emporium. of the spot on which this monument it rests, still as the silent heaven to which Canadian frontier to the tropics, and who 0- On the day on which Warren MI, -.NORWALK GAZE3IE. POETRY. stood was, by the donation of Hon. it soars, it is yet vocal, eloquent, in their m0re favored of Providence, has lived to Washington was commissioned as," C<taa- L>': HE subscribers have established a NEW COAL YARD James Russell, <vested in the Lodge, and undivided praise. Till the ponderous and an honored age, to enter into that reward mander-in Chief of all the continental BYINGTON, Editors oprietor T at Norwalk, on the east side siSf fgjjlkgra :>!. i! The Plague. A H. I of the Bridge, on Smith's Dock below the Pot* was ceded by them to the Bunker Hill well-compacted blocks of granite, which of gratitude and veneration, which it was forces raised or to be raised in defence of tery, where they intend to keep constantly on Thar*'* a eiiVie in our country, •• baleful u death, Monument Association in-1885, on condi Th» brother of sieknein, and pain; no. -

Notices of the American Mathematical Society Is Support, for Carrying out the Work of the Society

OTICES OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY 1989 Steele Prizes page 831 SEPTEMBER 1989, VOLUME 36, NUMBER 7 Providence, Rhode Island, USA ISSN 0002-9920 Calendar of AMS Meetings and Conferences This calendar lists all meetings which have been approved prior to Mathematical Society in the issue corresponding to that of the Notices the date this issue of Notices was sent to the press. The summer which contains the program of the meeting. Abstracts should be sub and annual meetings are joint meetings of the Mathematical Associ mitted on special forms which are available in many departments of ation of America and the American Mathematical Society. The meet mathematics and from the headquarters office of the Society. Ab ing dates which fall rather far in the future are subject to change; this stracts of papers to be presented at the meeting must be received is particularly true of meetings to which no numbers have been as at the headquarters of the Society in Providence, Rhode Island, on signed. Programs of the meetings will appear in the issues indicated or before the deadline given below for the meeting. Note that the below. First and supplementary announcements of the meetings will deadline for abstracts for consideration for presentation at special have appeared in earlier issues. sessions is usually three weeks earlier than that specified below. For Abstracts of papers presented at a meeting of the Society are pub additional information, consult the meeting announcements and the lished in the journal Abstracts of papers presented to the American list of organizers of special sessions. -

Market Buildings and Shops

Appendix 4 Market Buildings and Shops W1 Market Buildings, New / Comprehensively Rebuilt Of dimensions, the structure measures ca. 27.8 m by The study of market buildings in Late Antiquity is somewhat ca. 30.1 m, hand-measuring off the plan. difficult, when compared to Roman macella of the first Of architectural form, this phase of the complex saw a three centuries AD or market halls of the Hellenistic pe- substantial rebuilding, with the replacement of the inter- riod. Firstly, the architectural form of new market build- nal rooms and their courtyard by a design based on an aisle ings is less well-defined than it was in earlier centuries. and two naves, represented by two long walls with piers at When compared with ecclesiastical architecture from the “10 ft” (3.05 m) intervals, which may have supported vault- same period, late market buildings seem heterogeneous. ing over the central aisle, whilst the apse in the east wall Their identification rests on: (i) an inscription (as at Ostia); was levelled and a new wall built further back [although (ii) their form, echoing that of earlier structures (as at this ‘further back’ wall does not appear on the plan for this Geneva and at Athens, although the latter is too large); phase]. Along the street façade, to the west, the veranda (iii) their physical connection to a site where an exist- was replaced by a massive frontage supporting a portico or ing market building is well-attested (as at St. Bertrand or monumental entrance, with a foundation of 19 ft (5.79 m) Sagalassos); (iv) finds and paving details (Geneva produced by 7 ft (2.13 m) set down on its northern end, perhaps to a deposit of sheep and cattle bones; Ostia had holes for the support an arched side entrance, in the view of the report canopies of stalls). -

Lucha Libre Using Immigration to Attract US Fans

Lucha libre using immigration to attract US fans By RUSSELL CONTRERAS A ssociated Press ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. (AP) -- Defiantly waving an Arizona state flag, the self-described American patriot leaps into an octagon-shaped ring amid blaring music and loud boos from an overwhelmingly Latino audience, who hold aloft signs in Spanish supporting his masked Mexican opponents. "My name is RJ Brewer and I'm from Phoenix, Arizona," the wrestler proclaims in a video of a recent match provided by the promoter. Taunts from inside the arena get louder. He proceeds to rail against Mexican beer and to demand that people speak English. Then he points to the message painted on the backside of his red trunks: "SB1070" - a reference to Arizona's controversial immigration law. The crowd, some wearing masks of their favorite Mexican wrestlers, shrieks ever louder. He then brags that his "mother," Arizona Gov. Jan Brewer, is helping "save" America by pushing policies that limit immigration (he's not really her son). When his masked opponent in a red cape appears, the crowd erupts into cheers. Lucha libre - or "free wrestling" in Spanish - is a brand of Mexican wrestling that dates to the 1930s. The sport came north to the United States, along with Mexican immigrants, and over the years spawned clubs in some larger U.S. cities with large Latino communities. More recently, as the sport's promoters target growing Mexican immigrant and Mexican- American markets, they and their wrestlers' fictional personas have begun to adopt a more overtly political storyline revolving around immigration. It's a move akin to what U.S. -

Aght Jlliltonian

aGht jlliltonian : VOL. XLI DECEMBER, 1957 MILTON SCHOOL Headmaster: Mr. C. R. Messiter-Tooze Deputy Headmaster (Acting Headmaster, Third Term, 1957): Mr. F. G. Jackson Acting Deputy Headmaster, Third Term, 1957: Mr. L. Jones Master-in-Charge, Commercial and Technical Side: Mr. R. I. Leavis iHousemaster, Charter House: Mr. D. J. Avery. (Third Term, 1957: Mr. P. W. Mans) Housemaster, Pioneer House: Mr. F. G. Jackson. (Acting Housemaster, Third Term: Mr. N. L. Robertson) Sports Housemasters.-Birchenough: Mr. Cooper; Borrow: Mr. Kleyn; Fairbridge: Mr. N. L. Robertson; Heany: Mr. P. W. Mans. STAFF: Messrs. W. E. Adlard, L. Archell, D. J. Avery (retired at end of second term), D. C. Barbanell, F. W. Batchelor, D. R. Blezard, H. Birrell, L. D. Braithwaite, R. P. Cooper, P. P. Denborough, W. M. Engelbrecht, Miss U. N. Etheridge, Messrs. N. S. Freeman, P. H. Gifford, F. H. Gilbert, D. B. Glassbrook, F. A. Hambly, C. P. Kleyn, J. A. Labuschagne, G. Leech, J. B. McCallum, J. G. McGrady, D. MacMillan, P. W. Mans, Mrs. E. Milne, Mr. J. S. Oliver, Miss S. F. Parker, Mrs. E. M. Peakin, Messrs. R. R. B. Phillips, N. L. Robertson, C. W. Ross, P. L. Siebert, H. G. Smith, W. P. Speirs, Mrs. J. B. Sperring, Messrs. I. K. Stewart, B. Thomson, G. S. Todd, A. C. Tosh, W. F. Viljoen, W. D. G. Watt, A. P. Wellburn, A. N. Webb, D. B. Webb, Mrs. E. Young. Matrons.-Dining Hall, Senior Cook Matron: Mrs. A. J. L Bot'en; Assistant Cook Matron: Mrs. H. J. Stewart. Charter House: Sick Nurse Matron: Miss D. -

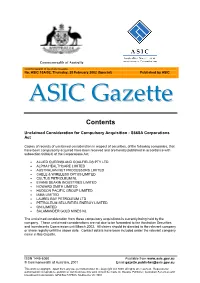

ASIC 10A/02, Thursday, 28 February 2002 (Special) Published by ASIC

= = `çããçåïÉ~äíÜ=çÑ=^ìëíê~äá~= = Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No. ASIC 10A/02, Thursday, 28 February 2002 (Special) Published by ASIC ^^ppff``==dd~~òòÉÉííííÉÉ== Contents Unclaimed Consideration for Compulsory Acquisition - S668A Corporations Act Copies of records of unclaimed consideration in respect of securities, of the following companies, that have been compulsorily acquired have been received and are hereby published in accordance with subsection 668A(4) of the Corporations Act: • ALLIED QUEENSLAND COALFIELDS PTY LTD • ALPHA HEALTHCARE LIMITED • AUSTRALIAN NUT PROCESSORS LIMITED • CABLE & WIRELESS OPTUS LIMITED • CULTUS PETROLEUM NL • EVANS DEAKIN INDUSTRIES LIMITED • HOWARD SMITH LIMITED • HUDSON PACIFIC GROUP LIMITED • IAMA LIMITED • LAUREL BAY PETROLEUM LTD • PETROLEUM SECURITIES ENERGY LIMITED • QNI LIMITED • SALAMANDER GOLD MINES NL The unclaimed consideration from these compulsory acquisitions is currently being held by the company. These unclaimed considerations are not due to be forwarded to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission until March 2003. All claims should be directed to the relevant company or share registry until the above date. Contact details have been included under the relevant company name in this Gazette. ISSN 1445-6060 Available from www.asic.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia, 2001 Email [email protected] This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all rights are reserved. Requests for authorisation to reproduce, publish or communicate -

Phylogeography of Douglas-Fir: Testing Hypotheses from the Fossil Record

PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF DOUGLAS-FIR: TESTING HYPOTHESES FROM THE FOSSIL RECORD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY PAUL FRANCIS GUGGER IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ADVISED BY JEANNINE CAVENDER-BARES SHINYA SUGITA JUNE 2010 © Paul F. Gugger 2010 Acknowledgments I am grateful to my advisors, Jeannine Cavender-Bares and Shinya Sugita, for their continuous support and encouragement. I also thank my committee members, Ruth Shaw, Peter Tiffin, and Bob Zink, for helpful conversations and comments on manuscripts. Keith Barker provided invaluable help with analyses and software. Thank you to Nick Deacon, Kari Koehler, Jessica Savage, and Gina Quiram for feedback on manuscripts, lab assistance, and friendship. Special thanks to those who have helped with field work: Antonio González Rodríguez, Barry Jaquish, Michael Stoehr, Carlos Acosta Gómez, Ken Oyama, and Victor Rocha Ramírez. Laura Strickland assisted with the Packrat Midden Database (Chapter 1), Cathy Whitlock and Feng Sheng Hu commented on manuscripts (Chapters 1 and 2, respectively), Art Dyke and Louis Robertson provided ice sheet data used in Figures 1.2, 1.3 and 2.1 (Chapters 1 and 2), Molly Bowen and the Cornell University Computational Biology Service Unit provided computer resources for IMa analyses (Chapter 2 and 3), and Antonio González Rodríguez and Hernando Rodríguez Correa performed lab work on chloroplast microsatellites and ecological niche modeling (Chapter 3). Finally, I express gratitude to those who were influential leading up to the dissertation: John Brick (Montville Township High School), Peter Mohler, Jason McLachlan, and Paul Manos. -

Climate Change and Carbon Sequestration: Vegetation Management Considerations1

WHITE PAPER F14-SO-WP-SILV-45 Climate Change and Carbon Sequestration: Vegetation Management Considerations1 David C. Powell; Forest Silviculturist Supervisor’s Office; Pendleton, OR Initial Version: DECEMBER 2011 Most Recent Revision: DECEMBER 2018 1 White papers are internal reports; they receive only limited review. Viewpoints expressed in this paper are those of the author – they may not represent official positions of USDA Forest Service. CONTENTS Background/Context ........................................................................................................... 3 Fig. 1: Empirical trends in fire season temperatures for eastern Oregon ................................. 4 Fig. 2: Projected increase in wildfire area burned ..................................................................... 5 Fig. 3: Restoration objectives for dry forests ............................................................................. 6 Fig. 4: Thinning and low-severity fire reduce the risk of stand-replacing fire ........................... 7 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 8 Fig. 5: Projected scenario for temperature and precipitation change for Washington ............ 9 Fig. 6: Reconstructed, 2000-year chronology of Palmer Drought Severity Index ................... 11 Silvicultural activities and climate change ........................................................................ 12 Intermediate cutting methods ................................................................................................