Other Austrians Tamara Ehs.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Íbúum Á Laugavegi Hótað Dagsektum

Berglind Ágústsdóttir lh hestar ræktaði hæst dæmda íslenska stóðhestinn ÍÞRÓTT • MENNING • LÍFSSTÍLL BLS. 6 ÞRIÐJUDAGUR 20. MAÍ 2008 Gæðingum á Þrír fá alþjóðleg LM fjölgar dómararéttindi GARÐAR THOR CORTES Nú liggja fyrir félagatöl hesta- Þrír íslenskir hestaíþrótta dómarar mannafélaganna fyrir árið 2008. fengu alþjóðleg dómararéttindi Sumarblóm fer að Sjóvá kvennahlaup ÍSÍ mun Vatn er lífsnauðsynlegt Fjöldi þátttakenda frá hverju fé- á dómararáðstefnu FEIF sem verða tímabært að gróð- fara fram í nítjánda sinn og hollasti svaladrykk- lagi á LM2008 miðast við þau. Tölu- var haldin á Hvanneyri 11. til 13. ursetja í garðinn. Blóm- laugardaginn 7. júní í urinn. Það hentar vel á verð fjölgun hefur orðið í félögun- apríl. Alls tóku 48 dómarar þátt í legt og fagurt umhverfi samstarfi við Lýðheilsu- milli mála og skemmir um og þar með fjöldi hrossa sem ráðstefnunni, þar af ellefu frá Ís- er gott fyrir heilsuna og stöð og er því kjörið að ekki tennur og er því gott hvar er betra að slaka á byrja að þjálfa sig og fara að hafa ætíð vatn við þau hafa rétt til að senda til þátt- landi. Eftir ráðstefnuna var haldið en í fallegum og friðsæl- út að skokka. Bolurinn í ár höndina. töku. Á LM2006 voru 112 í hverj- nýdómarapróf og stóðust þrír ís- um garði sem prýddur er er fjólublár og er þema ársins um flokki en á LM2008 eiga 119 lenskir dómarar prófið: Elísabeth dýrindis gróðri? Ef fólk er ekki „Heilbrigt hugarfar, hraustar þátttökurétt. Alls sendu félögin Jansen, Hulda G. Geirsdóttir og svo heppið að eiga garð má alltaf fá sér konur“. -

To Pray Again As a Catholic: the Renewal of Catholicism in Western Ukraine

To Pray Again as a Catholic: The Renewal of Catholicism in Western Ukraine Stella Hryniuk History and Ukrainian Studies University of Manitoba October 1991 Working Paper 92-5 © 1997 by the Center for Austrian Studies. Permission to reproduce must generally be obtained from the Center for Austrian Studies. Copying is permitted in accordance with the fair use guidelines of the US Copyright Act of 1976. The the Center for Austrian Studies permits the following additional educational uses without permission or payment of fees: academic libraries may place copies of the Center's Working Papers on reserve (in multiple photocopied or electronically retrievable form) for students enrolled in specific courses: teachers may reproduce or have reproduced multiple copies (in photocopied or electronic form) for students in their courses. Those wishing to reproduce Center for Austrian Studies Working Papers for any other purpose (general distribution, advertising or promotion, creating new collective works, resale, etc.) must obtain permission from the Center. The origins of the Ukrainian Catholic Church lie in the time when much of present-day Ukraine formed part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was then, in 1596, that for a variety of reasons, many of the Orthodox bishops of the region decided to accept communion with Rome.(1) After almost four hundred years the resulting Union of Brest remains a contentious subject.(2) The new "Uniate" Church formally recognized the Pope as Head of the Church, but maintained its traditional Byzantine or eastern rite, calendar, its right to ordain married men as priests, and its right to elect its own bishops. -

Download the Poster

1 4 Podlachia in north-east Poland has a considerable number of small towns, which had a great importance in the past, but with the passage of time, their role decreased due to political and economic changes. Until the Second World War, they had cultural, religious and linguistic diversity, with residents of Polish, Russian, Belarussian, German, Jewish and Tatar origin. After the war, some of them were gone, but their heritage was preserved. One of them is Supraśl, a small town near Białystok, capitol of the Podlachia region, north-eastern Poland. The best known monument of the town is the Suprasl Lavra (The Monastery 5 of the Annunciation), one of six Eastern Orthodox monasteries for men in Poland. Since September 2007 it is on Unesco’s Memory of the World list. It was founded in the 16th century by Aleksander Chodkiewicz, Marshall of the Great Duchy of Lithuania. In 1516, the Church of the Annunciation was consecrated. Some years later the monastery was expanded with the addition of the second church dedicated to the 2 Resurrection of Our Lord, which housed the monastery catacombs. Over time, the Supraśl Lavra became an important site of Orthodox culture. In 1609, the Monastery accepted the Union of Brest in the Polish- Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the Basilian Order (Unitas) took over its administration. In 1796, Prussian authorities confiscated the holdings of the monastery after the third Partition of Poland. 6 7 Nevertheless, it continued to play an important role in the religious life of the region as the seat of a newly created eparchy for those devout Ruthenians under Prussian rule, starting in 1797 and lasting until it fell under Russian rule after the Treaties of Tilsit in 1807. -

99 on Some International Regulations in Gaius's

REVIEW OF EUROPEAN AND COMPARATIVE LAW VOLUME XXXIX YEAR 2019 ON SOME INTERNATIONAL REGULATIONS IN GAIUS’S INSTITUTES Izabela Leraczyk* ABSTRACT The subject matter of the article concerns international regulations men- tioned by Gaius in his Institutes. The work under discussion, which is also a text- book for students of law, refers in several fragments to the institutions respected at the international level – the status of the Latins, peregrini dediticii and sponsio, contracted at the international arena. The references made by Gaius to the above institutions was aimed at comparing them to private-law solutions, which was intended to facilitate understanding of the norms relating to individuals that were comprised in his work. Key words: Gaius, Institutes, sponsio, peregrini dediticii, the Latins, international regulations 1. INTRODUCTION The work entitled Institutionum commentarii quattuor1 by the jurist Gaius2, living in the 2nd century AD, is one of the most important works * Izabela Leraczyk, Associate Professor in the Department of Roman Law, The John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, e-mail: [email protected], ORCID: 0000-0003-4723-8545. 1 This work was most probably written around the year 160 AD. Olga E. Telle- gen-Couperus, A Short History of Roman Law, London-New York: Routledge, 1993, 100. 2 Gaius, who is known only by his first name, is a rather mysterious figure. Despite of numerous hypotheses, it was not possible to reconstruct his life and even basic infor- mation, such as who he was and where he came from, is impossible to retrieve. Anthony 99 providing the grounds for research on the Roman law of the classical peri- od3. -

Czechoslovak-Polish Relations 1918-1968: the Prospects for Mutual Support in the Case of Revolt

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1977 Czechoslovak-Polish relations 1918-1968: The prospects for mutual support in the case of revolt Stephen Edward Medvec The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Medvec, Stephen Edward, "Czechoslovak-Polish relations 1918-1968: The prospects for mutual support in the case of revolt" (1977). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5197. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5197 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CZECHOSLOVAK-POLISH RELATIONS, 191(3-1968: THE PROSPECTS FOR MUTUAL SUPPORT IN THE CASE OF REVOLT By Stephen E. Medvec B. A. , University of Montana,. 1972. Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1977 Approved by: ^ .'■\4 i Chairman, Board of Examiners raduat'e School Date UMI Number: EP40661 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Senatus Aulicus. the Rivalry of Political Factions During the Reign of Sigismund I (1506–1548)

Jacek Brzozowski Wydział Historyczno-Socjologiczny Uniwersytet w Białymstoku Senatus aulicus. The rivalry of political factions during the reign of Sigismund I (1506–1548) When studying the history of the reign of Sigismund I, it is possible to observe that in exercising power the monarch made use of a very small and trusted circle of senators1. In fact, a greater number of them stayed with the King only during Sejm sessions, although this was never a full roster of sena- tors. In the years 1506–1540 there was a total of 35 Sejms. Numerically the largest group of senators was present in 1511 (56 people), while the average attendance was no more than 302. As we can see throughout the whole exa- mined period it is possible to observe a problem with senators’ attendance, whereas ministers were present at all the Sejms and castellans had the worst attendance record with absenteeism of more than 80%3. On December 15, 1534 1 This type of situation was not specific to the reign of Sigismund I. As Jan Długosz reports, during the Sejm in Sieradz in 1425, in a situation of attacks of the knights against the Council, the monarch suspended public work and summoned only eight trusted councellors. In a letter from May 3, 1429 Prince Witold reprimanded the Polish king for excessively yielding to the Szafraniec brothers – the Cracow Chamberlain – Piotr and the Chancellor of the Crown Jan. W. Uruszczak, Państwo pierwszych Jagiellonów 1386–1444, Warszawa 1999, p. 48. 2 In spite of this being such a small group, it must be noted that it was not internally coherent and homogenous. -

Yugoslav Destruction After the Cold War

STASIS AMONG POWERS: YUGOSLAV DESTRUCTION AFTER THE COLD WAR A dissertation presented by Mladen Stevan Mrdalj to The Department of Political Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of Political Science Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts December 2015 STASIS AMONG POWERS: YUGOSLAV DESTRUCTION AFTER THE COLD WAR by Mladen Stevan Mrdalj ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University December 2015 2 Abstract This research investigates the causes of Yugoslavia’s violent destruction in the 1990’s. It builds its argument on the interaction of international and domestic factors. In doing so, it details the origins of Yugoslav ideology as a fluid concept rooted in the early 19th century Croatian national movement. Tracing the evolving nationalist competition among Serbs and Croats, it demonstrates inherent contradictions of the Yugoslav project. These contradictions resulted in ethnic outbidding among Croatian nationalists and communists against the perceived Serbian hegemony. This dynamic drove the gradual erosion of Yugoslav state capacity during Cold War. The end of Cold War coincided with the height of internal Yugoslav conflict. Managing the collapse of Soviet Union and communism imposed both strategic and normative imperatives on the Western allies. These imperatives largely determined external policy toward Yugoslavia. They incentivized and inhibited domestic actors in pursuit of their goals. The result was the collapse of the country with varying degrees of violence. The findings support further research on international causes of civil wars. -

February 21, 1948 Report of the Special Action of the Polish Socialist Party in Prague, 21-25 February 1948

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified February 21, 1948 Report of the Special Action of the Polish Socialist Party in Prague, 21-25 February 1948 Citation: “Report of the Special Action of the Polish Socialist Party in Prague, 21-25 February 1948,” February 21, 1948, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Warsaw), file 217, packet 16, pp. 1-11. Translated by Anna Elliot-Zielinska. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/117117 Summary: In the midst of a cabinet crisis in Czechoslovakia that would lead to the February Communist coup, several delegates from the Polish Socialist Party were sent to Prague to spread socialist influence. The crisis is outlined, as well as a thorough report of the conference in Prague. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: Polish Contents: English Translation In accordance with the resolution of the Political Commission and General Secretariat of the Central Executive Committee (CKW) of the Polish Socialist Party (PPS), made late on the night of 20 February 1948, Com. Kazimierz Rusinek, Adam Rapacki, Henryk Jablonski, and Stefan Arski were delegated to go to Prague. This decision was made after a thorough analysis of the political situation in Czechoslovakia brought on by a cabinet crisis there. The goal of the delegation was to inform the Central Committee of the Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party (SD) about the basic stance of the PPS and possibly to influence the SD Central Committee in the spirit of leftist-socialist and revolutionary politics. The motive behind the decision of the Political Commission and General Secretariat was the fear that, from the leftist socialist point of view, the situation at the heart of SD after the Brno Congress was taking an unfavorable shape. -

The Politicization of Ethnicity As a Prelude to Ethnopolitical Conflict: Croatia and Serbia in Former Yugoslavia

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 6-2001 The Politicization of Ethnicity as a Prelude to Ethnopolitical Conflict: Croatia and Serbia in Former Yugoslavia Agneza Bozic-Roberson Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the International Relations Commons, Political Theory Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Bozic-Roberson, Agneza, "The Politicization of Ethnicity as a Prelude to Ethnopolitical Conflict: Croatia and Serbia in Former Yugoslavia" (2001). Dissertations. 1354. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1354 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POLITICIZATION OF ETHNICITY AS A PRELUDE TO ETHNOPOLITICAL CONFLICT: CROATIA AND SERBIA IN FORMER YUGOSLAVIA by Agneza Bozic-Roberson A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2001 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE POLITICIZATION OF ETHNICITY AS A PRELUDE TO ETHNOPOLITICAL CONFLICT: CROATIA AND SERBIA IN FORMER YUGOSLAVIA Agneza Bozic-Roberson, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2001 This interdisciplinary research develops a framework or a model for the study of the politicization of ethnicity, a process that transforms peaceful ethnic conflict into violent inter-ethnic conflict. The hypothesis investigated in this study is that the ethnopolitical conflict that led to the break up of former Yugoslavia was the result of deliberate politicization of ethnicity. -

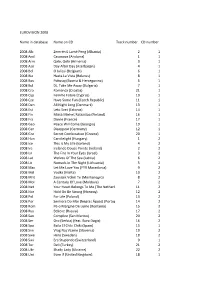

EUROVISION 2008 Name in Database Name on CD Track Number CD

EUROVISION 2008 Name in database Name on CD Track number CD number 2008 Alb Zemrën E Lamë Peng (Albania) 2 1 2008 And Casanova (Andorra) 1 1 2008 Arm Qele, Qele (Armenia) 3 1 2008 Aze Day After Day (Azerbaijan) 4 1 2008 Bel O Julissi (Belgium) 6 1 2008 Bie Hasta La Vista (Belarus) 8 1 2008 Bos Pokusaj (Bosnia & Herzegovina) 5 1 2008 Bul DJ, Take Me Away (Bulgaria) 7 1 2008 Cro Romanca (Croatia) 21 1 2008 Cyp Femme Fatale (Cyprus) 10 1 2008 Cze Have Some Fun (Czech Republic) 11 1 2008 Den All Night Long (Denmark) 13 1 2008 Est Leto Svet (Estonia) 14 1 2008 Fin Missä Miehet Ratsastaa (Finland) 16 1 2008 Fra Divine (France) 17 1 2008 Geo Peace Will Come (Georgia) 19 1 2008 Ger Disappear (Germany) 12 1 2008 Gre Secret Combination (Greece) 20 1 2008 Hun Candlelight (Hungary) 1 2 2008 Ice This Is My Life (Iceland) 4 2 2008 Ire Irelande Douze Pointe (Ireland) 2 2 2008 Isr The Fire In Your Eyes (Israel) 3 2 2008 Lat Wolves Of The Sea (Latvia) 6 2 2008 Lit Nomads In The Night (Lithuania) 5 2 2008 Mac Let Me Love You (FYR Macedonia) 9 2 2008 Mal Vodka (Malta) 10 2 2008 Mnt Zauvijek Volim Te (Montenegro) 8 2 2008 Mol A Century Of Love (Moldova) 7 2 2008 Net Your Heart Belongs To Me (The Netherlands) 11 2 2008 Nor Hold On Be Strong (Norway) 12 2 2008 Pol For Life (Poland) 13 2 2008 Por Senhora Do Mar (Negras Águas) (Portugal) 14 2 2008 Rom Pe-o Margine De Lume (Romania) 15 2 2008 Rus Believe (Russia) 17 2 2008 San Complice (San Marino) 20 2 2008 Ser Oro (Serbia) (feat. -

Sacred Places in Lviv – Their Changing Significance and Functions

PrACE GEOGrAFICznE, zeszyt 137 Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej UJ Kraków 2014, 91 – 114 doi : 10.4467/20833113PG.14.011.2156 Sacred placeS in lviv – their changing Significance and functionS Małgorzata Flaga Abstract : In the paper, issues of a multitude of functions of sacred places in Lviv are considered. The problem is presented on the example of selected religious sites that were established in distinct periods of the development of the city and refers to different religious denomina- tions. At present, various functions are mixing in the sacred complexes of Lviv. The author tries to formulate some general conclusions concerning their contemporary role and leading types of activity. These findings are based, most of all, on analyses of the facts related to the history of Lviv, circumstances of its foundation, various transformations, and modern func- tions of the selected sites. Keywords : Lviv, Western Ukraine, religious diversity, functions of religious sites introduction Lviv, located in the western part of Ukraine, is a city with an incredibly rich his- tory and tradition. It was founded in an area considered to be a kind of political, ethnic and religious borderland. For centuries the influence of different cultures, ethnic and religious groups met there and the city often witnessed momentous historical events affecting the political situation in this part of Europe. The com- munity of the thriving city was a remarkable mosaic of nationalities and religious denominations from the very beginning. On the one hand, these were representa- tives of the Latin West ( first – Catholics, later on – Protestants ), on the other hand – the Byzantine East. -

The Croats Under the Rulers of the Croatian National Dynasty

THE CROATS Fourteen Centuries of Perseverance Publisher Croatian World Congress (CWC) Editor: Šimun Šito Ćorić Text and Selection of Illustrations Anđelko Mijatović Ivan Bekavac Cover Illustration The History of the Croats, sculpture by Ivan Meštrović Copyright Croatian World Congress (CWC), 2018 Print ITG d.o.o. Zagreb Zagreb, 2018 This book has been published with the support of the Croatian Ministry of culture Cataloguing-in-Publication data available in the Online Catalogue of the National and University Library in Zagreb under CIP record 001012762 ISBN 978-953-48326-2-2 (print) 1 The Croats under the Rulers of the Croatian National Dynasty The Croats are one of the oldest European peoples. They arrived in an organized manner to the eastern Adriatic coast and the re- gion bordered by the Drina, Drava and Danube rivers in the first half of the seventh century, during the time of major Avar-Byzan- tine Wars and general upheavals in Europe. In the territory where they settled, they organized During the reign of Prince themselves into three political entities, based on the previ Branimir, Pope John VIII, ous Roman administrative organizations: White (western) the universal authority at Croatia, commonly referred to as Dalmatian Croatia, and Red the time, granted (southern) Croatia, both of which were under Byzantine su Croatia international premacy, and Pannonian Croatia, which was under Avar su recognition. premacy. The Croats in Pannonian Croatia became Frankish vassals at the end of the eighth century, while those in Dalmatia came under Frankish rule at the beginning of the ninth century, and those in Red Croatia remained under Byzantine supremacy.