December 2016 Sigar-17-17-Sp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

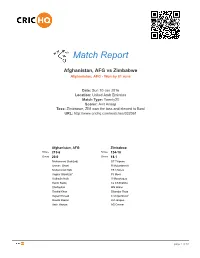

Match Report

Match Report Afghanistan, AFG vs Zimbabwe Afghanistan, AFG - Won by 81 runs Date: Sun 10 Jan 2016 Location: United Arab Emirates Match Type: Twenty20 Scorer: Anit Anoop Toss: Zimbabwe, ZIM won the toss and elected to Bowl URL: http://www.crichq.com/matches/332061 Afghanistan, AFG Zimbabwe Score 215-6 Score 134-10 Overs 20.0 Overs 18.1 Mohammad Shahzad† DT Tiripano Usman Ghani R Mutumbami† Mohammad Nabi TS Chisoro Asghar Stanikzai* PJ Moor Gulbadin Naib H Masakadza Karim Sadiq CJ Chibhabha Shafiqullah MN Waller Rashid Khan Sikandar Raza Sayed Shirzad E Chigumbura* Dawlat Zadran LM Jongwe Amir Hamza AG Cremer page 1 of 34 Scorecards 1st Innings | Batting: Afghanistan, AFG R B 4's 6's SR Mohammad . 1 1 . 6 1 4 2 . 1 . 4 . 1 . 1 4 . 4 1 4 . 1 6 4 4 1 1 . 1 . 6 1 not out 118 67 10 8 176.12 6 6 1 6 4 . 1 6 . 6 1 2 1 1 . 4 1 1 . 1 4 2 1 2 . 1 Shahzad† Usman Ghani 1 . 2 1 1 . // b AG Cremer 5 13 0 0 38.46 Asghar . 1 . 6 1 1 1 . 4 4 . // b LM Jongwe 18 12 2 1 150.0 Stanikzai* Karim Sadiq 2 4 2 4 . // c PJ Moor b TS Chisoro 12 5 2 0 240.0 Shafiqullah . 1 6 1 . // c PJ Moor b CJ Chibhabha 8 6 0 1 133.33 Mohammad 1 1 . 6 2 1 1 . 4 6 . // b DT Tiripano 22 12 1 2 183.33 Nabi Gulbadin Naib 1 6 2 1 2 1 // run out (DT Tiripano/R Mutumbami†) 13 6 0 1 216.67 Extras (w 6, nb 1, b 8, lb 4) 19 Total (6 wickets; 20.0 overs) 215 10.75 RPO Did Not Bat:["Rashid Khan", "Sayed Shirzad", "Dawlat Zadran", "Amir Hamza"] Fall of Wicket: 43-1 (Usman Ghani 6.1 ov ), 116-2 (Asghar Stanikzai 11.4 ov ), 145-3 (Karim Sadiq 13.3 ov ), 154-4 (Shafiqullah 14.4 ov ), 201-5 (Mohammad Nabi 18.5 ov ), 215-6 (Gulbadin Naib 19.6 ov ) Bowling: Zimbabwe, ZIM O M R W EC AV EX DT Tiripano 4.0 0 36 1 9.00 36.00 (w 3) TS Chisoro 4.0 0 25 1 6.25 25.00 (w 1) LM Jongwe 4.0 0 34 1 8.50 34.00 (w 1) CJ Chibhabha 4.0 0 56 1 14.00 56.00 AG Cremer 3.0 0 35 1 11.67 35.00 (w 1) Sikandar Raza 1.0 0 17 0 17.00 - (nb 1) Notes: 50 up for Afghanistan at 7.1. -

Providence Stadium Beausejour Stadium Kensington Oval

Thursday 29th April, 2010 15 The ICC World Twenty20 2010 will be contested by Teams 12 teams which have been ‘seeded’ and divided into four groups: Australia New Zealand Group A Group B Group C Group D Michael Clarke (captain) Daniel Vettori (captain) Pakistan Sri Lanka South Africa West Indies Daniel Christian Shane Bond Bangladesh New Zealand India England Brad Haddin (wicketkeeper) Ian Butler Australia Zimbabwe Afghanistan Ireland Nathan Hauritz Martin Guptill David Hussey Gareth Hopkins (wicketkeeper) Brendon McCullum Michael Hussey How matches are contested; (wicketkeeper) Mitchell Johnson 1. The top two seeded teams are allocated slots in Nathan McCullum Brett Lee the Super Eight stage regardless of where they finish Kyle Mills Dirk Nannes in their group. The Super Eight stage is not determined Rob Nicol on winners and runners-up. Tim Paine Jacob Oram For example, Pakistan are designated A1 and Steven Smith Aaron Redmond Bangladesh A2 in their group. If they both qualify then, Shaun Tait Jesse Ryder regardless of who wins the group, Pakistan will go into David Warner Tim Southee Group E and Bangladesh Group F. If, however, Shane Watson Scott Styris Australia qualifies instead of, say, Bangladesh, they Cameron White Ross Taylor will take their designation as A2 and move into Group F. Afghanistan Pakistan 2. Each team will play every other team in its group. 3. No points from the Group stage will be carried Nowroz Mangal (captain) Shahid Afridi (captain) forward to the Super Eight series. Asghar Stanikzai Abdul Razzaq Abdur Rehman 4. The top two teams from each group in the Super Dawlat Ahmadzai Fawad Alam Eight series of the competition will progress to the Hamid Hassan semi-finals where the team placed first in Group E will Hammad Azam Karim Sadiq Kamran Akmal (wicketkeeper) play the team placed second in Group F and the team Mirwais Ashraf Khalid Latif placed first in Group F will play the team placed sec- Mohammad Nabi Misbah-ul-Haq ond in Group E. -

ICC U19 Cricket World Cup 2020

MEDIA GUIDE Version 3 / January 2019 2 The ICC would like to thank all its Commercial Partners for their support of the ICC U19 Cricket World Cup South Africa 2020. ICC U19 CRICKET WORLD CUP 3 I’d like to welcome all members WELCOME of the media here in South Africa and those around the world who ICC CHIEF EXECUTIVE will be covering the ICC U19 Cricket World Cup 2020. This is the second time that South Africa has On behalf of the ICC, I would like to take this hosted the tournament which is close to the opportunity to thank Cricket South Africa, its staff, hearts of all of us at ICC and is considered a very ground authorities and volunteers in helping us important event on our calendar. It provides organize this important event. I would also like players with an unrivaled experience of global to thank our commercial and broadcast partners events and a real flavour of international cricket for their support in making our events so special at senior level, while cricket fans around the world and taking them to the widest possible audience. can watch tomorrow’s stars in action either in A word of appreciation is likewise due to my person, on television or via the ICC digital channels. colleagues at the ICC, who have worked so hard in preparation for this event. A host of past and present stars have come through this system and the fact that a number of the I would also like to thank all members of the world’s best current players including Virat Kohli, media for your continued support of this event, Steve Smith, Joe Root, Kane Williamson, Sarfraz whether you are here in person or following from Ahmed and Dinesh Chandimal have all figured in your respective countries around the world, the past ICC U19 World Cups, demonstrates the calibre coverage you drive is crucial to the future success of cricketers we can expect to see during this event. -

Afghanistan Win to Draw Series

SPORTS SATURDAY, JULY 26, 2014 Jadeja fined over Anderson incident LONDON: India all-rounder Ravindra Jadeja has month’s fourth Test on his Lancashire home been fined 50 percent of his match fee after being ground of Old Trafford and the series finale at The found guilty of “conduct contrary to the spirit of Oval in south London. the game”, the International Cricket Council However, Lewis, like Boon, does have the announced yesterday. However, he was not option to downgrade the charge facing Anderson banned and remains free to play in the rest of the if he finds him not guilty of a Level Three infringe- ongoing five-Test series with England. ment. Jadeja, 25, was involved in an incident with Level Two offences carry a fine of between 50- England seamer James Anderson during the lunch 100 percent of a player’s match fee and/or up two break on the second day of the drawn first Test at suspension points, which equates to a ban of one Nottingham’s Trent Bridge ground on July 10. Test. India lead the series 1-0 after their 95-run win England charged Jadeja with a Level Two in the second Test at Lord’s on Monday, the match offence under the ICC’s code of conduct in retalia- ending with Jadeja’s run out of Anderson after tion for India bringing a more serious Level Three which the players were seen shaking hands. — AFP charge against Anderson for allegedly “abused and pushing” Jadeja. However, ICC match referee David Boon, following a two-and-a-half hour hearing in COLOMBO: Sri Lankan bowler Suranga Lakmal stops the ball during the second day of Southampton on Thursday involving the two play- the second Test match between Sri Lanka and South Africa at the Sinhalese Sports Club ers, their lawyers and representatives of both (SSC) Ground. -

Ghani Thanks US Troops for Sacrifices in Afghanistan

Eye on the News [email protected] Truthful, Factual and Unbiased Vol:IX Issue No:228 Price: Afs.15 TUESDAY . MARCH 24 . 2015 -Hamal 04, 1394 HS www.afghanistantimes.af www.facebook.com/ afghanistantimeswww.twitter.com/ afghanistantimes Afghanistan Ghani thanks will be GRAVEYARD US troops FOR DAESH: GHANI AIDE for sacrifices WASHINGTON: With the in- creasing capabilities and strength of the security forces, Afghanistan will prove a graveyard of Daesh, a confident presidential spokesman in Afghanistan said ahead of Afghan-US talks at Camp David. Ajmal Obaid Abidy made the assertion during an inter- view Pajhwok Afghan News hours after President Ashraf Ghani and his CEO Dr Abdullah Abdullah ar- rived in Washington for talks with American leaders. He said the talks would focus not only on security KABUL: The ex-President Hamid Karzai talking to religious scholars from Nangarhar, Laghman, Kunar and aspects of the relationship, but also Nuristan provinces here on Monday. The scholars lauded Hamid Karzai s nation-building efforts. on economic self-reliance, a goal articulated by Ghani after coming to power last year. Stability of Efforts ongoing Afghanistan is key to stability of ANSF all set to forestall the region and Islamic countries. to reopen Of course, the United States can play a very significant role in cre- closed schools ation of such consensus (among DAESH THREAT, SAYS NDS regional players and Islamic coun- tries), he added. On Sunday in Zabul Abdul Zuhoor Qayomi North Waziristan. We have devised al allies of Afghanistan to give mod- a special mechanism for fight against ern weapons to Afghan security forc- evening, Secretary of State, John QALAT: Education officials say Kerry hosted a dinner for Ghani ational Directorate of Secu ISIS and we have sent the mecha- es. -

Govt. Leaders Agree to Rollout E-NIC

Add: V-137, Street-6, Phase, 4, District 6, Add: V-137, Street-6, Phase, 4, District 6, Shahrak Omed Sabz, Kabul Shahrak Omed Sabz, Kabul Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Phone: 0093 (799) 005019/777-005019 Phone: 0093 (799) 005019/777-005019 www.outlookafghanistan.net www.thedailyafghanistan.com Back Page March 01, 2017 Ghazni Kandahar Jalalabad Cloudy Clear Clear Mazar Partly Herat Partly Bamayan Clear Kabul Cloudy Cloudy Daily Cloudy Outlook 19°C 5°C 16°C 14°C 15°C 0°C 10°C Weather 4°C °C 9°C -6°C 3°C 3 -10°C 0°C Forcast Pakistan Once Again Weighing Border- Govt. Leaders Agree Fencing Option PESHAWAR - As Kabul ghanistan does not recognise and Islamabad continue to as a formal border, has been squabble over terror safe ha- closed for almost two weeks. vens, Pakistan has decided Despite a flurry of diplomat- KABUL - The government to Rollout E-NIC to fence the border at certain ic activity and protests from leaders have finally agreed points, says a security offi- the Afghan side, the frontier on the legal aspects of the cial. is yet to be reopened. electronic-National Identity “Following a spate of high- Kabul angrily reacted to Pa- Cards (e-NIC), the office of casualty attacks across the kistan’s plan to fence certain the second vice president, country, Pakistan’s federal parts of the border in April Mohammad Sarwar Danish, government has decided to 2016. A number of such at- said on Tuesday. fence selected parts of the tempts by Pakistan in recent According to a Danish’s aide, border with Afghanistan,” years have prompted howls President Ashraf Ghani is the official told Pajhwok Af- of protests from the Afghan likely to sign an order for the ghan News. -

List of Overseas Cricketers for the Bangabandhu Draft

BANGABANDHU BANGLADESH PREMIER LEAGUE (BBPL) T20 -2019 SL No. PLAYER COUNTRY PLAYING ROLE PLAYING STYLE EXPECTED GRADE AVAILABILITY 1 Imran Qayyum England Left Arm Orthodox Right Hand D 16/12/2019 to 11/01/2020 2 Niroshan Dickwella Sri Lanka WK/Batsman Left Hand B Full 3 Suranga Lakmal Sri Lanka Medium Fast Bowler Right Hand D Full 4 Isuru Udana Sri Lanka All Rounder/Medium Fast Bowler Right Hand A Full 5 Nuwan Pradeep Sri Lanka Medium Fast Bowler Right Hand C Full 6 Shehan Jayasurya Sri Lanka All rounder/Off Spin Left Hand D Full 7 Milinda Siriwardana Sri Lanka All Rounder/Left Arm Orthodox Left Hand D Full 8 Oshada Fernando Sri Lanka All Rounder/Leg Spin Right Hand D Full 9 Sadeera Samarawickrama Sri Lanka WK/Batsman Right Hand D Full 10 Dinesh Chandimal Sri Lanka WK/Batsman Right Hand C Full 11 Vishwa Fernando Sri Lanka Medium Fast Bowler Left Hand D Full 12 Lahiru Madushanka Sri Lanka All Rounder/ Medium Fast Bowler Right Hand D Full 13 Thikshila De Silva Sri Lanka All Rounder/Medium Fast Bowler Left Hand D Full 14 Kevin Koththigoda Sri Lanka Leg spin Left Hand D Full 15 Nimanda Madushanka Sri Lanka All Rounder/Medium Fast Bowler Right Hand D Full 16 Kyle Abbott South Africa Medium Fast Bowler Right Hand B 19/12/19 to 11/1/20 16 Kyle Abbott South Africa Medium Fast Bowler Right Hand B 19/12/19 to 11/1/20 17 Hardus Viljoen South Africa Medium Fast Bowler Right Hand B 19/12/19 to 11/1/20 18 David Wiese South Africa All Rounder/Medium Fast Bowler Right Hand B Full 19 Ahmed Shehzad Pakistan Top Order Batsman Right Hand B Full 20 Anwar -

UNAMA NEWS Kabul, Afghanistan

_____________________________________________________________________ Compiled by the Strategic Communication and Spokespersons Unit UNAMA NEWS Kabul, Afghanistan United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan 29 April - 6 May 2010 Website: http://unama.unmissions.org ____________________________________________________________ World Press Freedom Day: Freedom of Information 3 May 2010 - Since the fall of the Taliban in 2001 Afghanistan has seen a remarkable boom in the media scene. Today the Director-General of UNESCO, says the Day is "an occasion to remember the importance of our right to know." Message from Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO on the occasion of World Press Freedom Day 3 May 2010 This World Press Freedom Day, whose theme is Freedom of Information, offers us an occasion to remember the importance of our right to know. Freedom of Information is the principle that organisations and governments have a duty to share or provide ready access to information they hold, to anyone who wants it, based on the public’s right to be informed. The right to know is central for upholding other basic rights, for furthering transparency, justice and development. Hand-in- UN and Afghan Government call for “Freedom of Information” on hand with the complementary notion of freedom of expression, it underpins democracy. World Press Freedom Day We may not consciously exercise our right to know. But each 3 May 2010 - The United Nations and the Government of Afghanistan today time we pick up a newspaper, turn on the TV or radio news, or emphasized the need for freedom of information and the importance of a free go on the Internet, the quality of what we see or hear depends press at a day-long event in Kabul to mark World Press Freedom Day, on these media having access to accurate and up to date celebrated world-wide on 3 May. -

The Great Game: the Rise of Afghan Cricket from Exodus and War

The Great Game: The rise of Afghan cricket from exodus and war Author : Kate Clark Published: 28 March 2017 Downloaded: 5 September 2018 Download URL: https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/the-great-game-the-rise-of-afghan-cricket-from-exodus-and-war/?format=pdf Afghanistan continues to make inroads into the world of cricket. The men’s team has progressed from being a disorganised band of reckless hitters of the ball in the early 2000s to a well-balanced team. Two Afghans recently got contracts to play in the biggest cricket league in the world, the Indian Premier League, with deals worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. AAN’s cricket-loving Sudhanshu Verma and ‘not very interested in cricket’ Kate Clark look at how, in two decades, Afghan men have come to compete with the big boys of the game. Afghan women’s cricket, though, they say, has barely begun. For any reader who finds cricket something of a mystery, a brief description of how the game works can be found in an Appendix. For readers interested in sport generally, they might also like to read our reports on Afghan football, brought together in a dossier here. 18-year-old Afghan national team player, Rashid Khan, was in Harare, the capital of Zimbabwe, playing for Afghanistan in a One Day International series on 20 February 2017, when bidding for 1 / 13 the Indian Premier League (1) began. The IPL is the biggest, richest cricket league in the world, watched by millions and attracting the world’s top players. Every year before the season starts, the eight IPL teams bid for new players. -

Rashid Takes 4 Wkts in Four Balls As Afghanistan Win Against Ireland

Bancroft scores 138 on first-class return after ban SYDNEY: Australian opening batsman Cameron Bancroft scored an unbeaten 138 on his return to first-class cricket after a nine-month ball-tampering ban. Bancroft was suspended, along with then Australia captain SPORTS 13 Steve Smith and David Warner, after the incident during last year’s third Test against South Africa. His ban ended in December and he played in the Big Bash League but this was his red-ball return for Western FREE PRESS Australia. Australia travel to England for five Ashes Tests this summer. INDORE | TUESDAY | FEBRUARY 26, 2019 WGC-MEXICO CHAMPIONSHIP IT WAS DIFFICULT TRACK EVEN FOR A PLAYER LIKE DHONI: MAXWELL VISAKHAPATNAM: Mahendra Singh Dhoni once again drew flak for his slow strike-rate against East Bengal-Real Australia in the first T20 International but Glenn Maxwell feels that on a low and slow track, that was all the former India captain could have done. Dhoni managed 29 off 37 balls in India’s below-par 126 for 7 on a track where the ball was not coming onto the bat. To be fair to Dhoni, a clutch of Dustin Johnson wins Kashmir game shifted wickets fell and he also had to stem the rot with Yuzvendra Chahal at the other end. to Delhi from Srinagar AGENCIES their game in the region 20th PGA Tour title Kolkata despite AIFF’s security as- surances. AGENCIES Johnson, 34, becomes only the fifth East Bengal’s I-League Minerva had approached Mexico player in the last 50 years to reach 20 game against fellow title the high court challenging PGA Tour wins before the age of 35, put- aspirants Real Kashmir AIFF’s refusal to postpone American Dustin Johnson claimed his ting him in the company of only Woods, FC was on Monday shifted the February 18 match. -

Match Report

Match Report Afghanistan, AFG vs West Indies, WI West Indies, WI - Won by 7 wickets Date: Tue 06 Jun 2017 Location: West Indies - Saint Christopher-Nevis-Anguilla Match Type: Twenty20 Scorer: Prashob P Toss: Afghanistan, AFG won the toss and elected to Bat URL: http://www.crichq.com/matches/526727 Afghanistan, AFG West Indies, WI Score 146-6 Score 147-3 Overs 20.0 Overs 19.2 Gulbadin Naib CAK Walton† Noor Ali Zadran E Lewis Asghar Stanikzai* MN Samuels Javed Ahmadi LMP Simmons Mohammad Nabi CR Brathwaite* Karim Janat JN Mohammed Shafiqullah .† R Powell Najibullah Zadran SP Narine Rashid Khan JE Taylor Amir Hamza S Badree Shapoor Zadran KOK Williams page 1 of 34 Scorecards 1st Innings | Batting: Afghanistan, AFG R B 4's 6's SR Noor Ali . 2 4 . 6 1 . 4 4 4 . 6 . 4 . // b KOK Williams 35 19 5 2 184.21 Zadran Javed Ahmadi . // lbw b S Badree 0 2 0 0 0.0 Asghar . 2 1 . 4 . 1 1 . 1 1 . 1 1 . // c KOK Williams b R Powell 13 23 1 0 56.52 Stanikzai* Mohammad 2 . 1 . 1 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 1 . 1 . 6 2 4 . 2 2 . 1 1 6 4 . // c R Powell b KOK Williams 38 30 2 2 126.67 Nabi Karim Janat 1 . 1 1 . 1 1 1 1 1 . // c E Lewis b JE Taylor 8 17 0 0 47.06 Shafiqullah .† . 1 . 1 . 3 4 1 . 1 6 4 4 . // b KOK Williams 25 15 3 1 166.67 Najibullah . 1 . 1 2 4 1 1 not out 10 9 1 0 111.11 Zadran Gulbadin Naib . -

Bi-Weekly Bulletin 27 April 2020 - 11 May 2020

INTEGRITY IN SPORT Bi-weekly Bulletin 27 April 2020 - 11 May 2020 Photos International Olympic Committee INTERPOL is not responsible for the content of these articles. The opinions expressed in these articles are those of the authors and do not represent the views of INTERPOL or its employees. INTERPOL Integrity in Sport Bi-Weekly Bulletin 27 April 2020 - 11 May 2020 SENTENCES/SANCTIONS Afghanistan Afghanistan cricketer Shafiqullah Shafaq handed six-year match-fixing ban Afghanistan wicketkeeper-batsman Shafiqullah Shafaq was banned from all forms of cricket for six years on Sunday after accepting charges relating to match-fixing. The Afghanistan Cricket Board (ACB) said the 30-year-old had fixed or tried to fix matches in inaugural Afghanistan Premier League T20 in 2018 and in the 2019 Bangladesh Premier League. "Shafaq has been charged for breaches of the anti-corruption code which relates to fixing or contriving in any way or otherwise influencing improperly, or being a party to any agreement," the ACB announced in a statement. It added: "Shafaq was also charged for seeking, accepting, offering or agreeing to accept any bribe or other reward to fix or to contrive in any way or otherwise to to influence improperly the result, progress, conduct or any other aspect of any domestic match." Match fixing has rocked international cricket in the last two decades with life bans for the late South African skipper Hansie Cronje, Indian captain Mohammad Azharuddin and Pakistan's Salim Malik. But this is the first case involving a player from Afghanistan since the country had a fairytale rise in international cricket in 2009.