A Modular Sensor Suite for Underwater Reconstruction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dive Lights Assessment Report

System Assessment and Validation for Emergency Responders (SAVER) Dive Lights Assessment Report September 2015 Prepared by Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center Atlantic Approved for public release, distribution is unlimited. The Dive Lights Assessment Report was funded under Interagency Agreement No. HSHQPM-14-X-00064 from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Science and Technology Directorate. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Government. Reference herein to any specific commercial products, processes, or services by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the U.S. Government. The information and statements contained herein shall not be used for the purposes of advertising, nor to imply the endorsement or recommendation of the U.S. Government. With respect to documentation contained herein, neither the U.S. Government nor any of its employees make any warranty, express or implied, including but not limited to the warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose. Further, neither the U.S. Government nor any of its employees assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed; nor do they represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. The cover photo and images included herein were provided by the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center Atlantic. FOREWORD The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) established the System Assessment and Validation for Emergency Responders (SAVER) Program to assist emergency responders making procurement decisions. -

How to Make Solo Rebreather Diving Safer

technical So,what’s Say that you dive on your own with wrong about a rebreather and wait for the reactions. matters bringing a Rubiks cube You’ll hear some nasty comments about along on a dive? you being an accident waiting to happen Discussions about diving never did a solo dive. The other 92 percent have done at least a few Column by are very often boring— solo dives, with 33 percent doing Cedric Verdier always the same stories mostly solo diving. about numerous sharks Of course, a poll only represents dangerously close, strong the opinion of a few individuals current ripping a mask off who want to answer the questions. It cannot be considered as the “big or friendly dolphins play- picture” of the entire rebreather ing during a deco stop. diver community. Nevertheless, it We heard them so many shows that some rebreather divers times. keep on diving solo, even if the perceived risk is so high… So, if you want to have some Why people don’t dive fun, simply say that you dive on solo with a rebreather? your own with a rebreather and Simply because that’s one wait for the reactions. You’ll hear of the most basic rules some nasty comments about one learns during the you being an accident waiting Open Water Diver to happen, and some people course: “Never dive will clearly show you their option alone”. It’s so famous about your mental health. that it’s almost a dogma. And it sounds Why? Because everybody so logical? knows that CCR Solo diving is the most stupid thing to do on Earth 1. -

Winds, Waves, and Bubbles at the Air-Sea Boundary

JEFFREY L. HANSON WINDS, WAVES, AND BUBBLES AT THE AIR-SEA BOUNDARY Subsurface bubbles are now recognized as a dominant acoustic scattering and reverberation mechanism in the upper ocean. A better understanding of the complex mechanisms responsible for subsurface bubbles should lead to an improved prediction capability for underwater sonar. The Applied Physics Laboratory recently conducted a unique experiment to investigate which air-sea descriptors are most important for subsurface bubbles and acoustic scatter. Initial analyses indicate that wind-history variables provide better predictors of subsurface bubble-cloud development than do wave-breaking estimates. The results suggest that a close coupling exists between the wind field and the upper-ocean mixing processes, such as Langmuir circulation, that distribute and organize the bubble populations. INTRODUCTION A multiyear series of experiments, conducted under the that, in the Gulf of Alaska wintertime environment, the auspices of the Navy-sponsored acoustic program, Crit amount of wave-breaking activity may not be an ideal ical Sea Test (CST), I has been under way since 1986 with indicator of deep bubble-cloud formation. Instead, the the charter to investigate environmental, scientific, and penetration of bubbles is more closely tied to short-term technical issues related to the performance of low-fre wind fluctuations, suggesting a close coupling between quency (100-1000 Hz) active acoustics. One key aspect the wind field and upper-ocean mixing processes that of CST is the investigation of acoustic backscatter and distribute and organize the bubble populations within the reverberation from upper-ocean features such as surface mixed layer. waves and bubble clouds. -

Wetsuits Raises the Bar Once Again, in Both Design and Technological Advances

Orca evokes the instinct and prowess of the powerful ruler of the seas. Like the Orca whale, our designs have always been organic, streamlined and in tune with nature. Our latest 2016 collection of wetsuits raises the bar once again, in both design and technological advances. With never before seen 0.88Free technology used on the Alpha, and the ultimate swim assistance WETSUITS provided by the Predator, to a more gender specific 3.8 to suit male and female needs, down to the latest evolution of the ever popular S-series entry-level wetsuit, Orca once again has something to suit every triathlete’s needs when it comes to the swim. 10 11 TRIATHLON Orca know triathletes and we’ve been helping them to conquer the WETSUITS seven seas now for more than twenty years.Our latest collection of wetsuits reflects this legacy of knowledge and offers something for RANGE every level and style of swimmer. Whether you’re a good swimmer looking for ultimate flexibility, a struggling swimmer who needs all the buoyancy they can get, or a weekend warrior just starting out, Orca has you covered. OPENWATER Swimming in the openwater is something that has always drawn those types of swimmers that find that the largest pool is too small for them. However open water swimming is not without it’s own challenges and Orca’s Openwater collection is designed to offer visibility, and so security, to those who want to take on this sport. 016 SWIMRUN The SwimRun endurance race is a growing sport and the wetsuit requirements for these competitors are unique. -

Public Safety Scuba Diving

Industry Guide 47 A Guide to Public Safety Diving N.C. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Division N.C. Department of Labor 1101 Mail Service Center Raleigh, NC 27699-1101 Cherie Berry Commissioner of Labor N.C. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Program Cherie Berry Commissioner of Labor OSHA State Plan Designee Kevin Beauregard Deputy Commissioner for Safety and Health Scott Mabry Assistant Deputy Commissioner for Safety and Health Tom Savage Standards Officer Author Acknowledgments A Guide to Public Safety Diving has been prepared with materials and information from the General Industry Standards, 29 CFR 1910, Subpart T—Commercial Diving Operations, and OSHA Instruction CPL 02-00-151 (U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration). This guide also contains information from sources such as U.S. Navy Diving Manual, National Association of Search and Rescue, California Department Fish and Game Diving Safety Manual, and the National Fire Protection Association, NFPA 1670—Standard on Operations and Technical Search and Rescue. Through an existing alliance established between the N.C. Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Divi- sion and the North Carolina Public Safety Divers’ Association (PSDA), a collaborative effort was established to make this guide possible. The PSDA board of directors provided expertise involving public safety diving in sharing best practices and technical knowledge. A special thanks to Chuck Elgin, North Carolina Underwater Response Team, for his dedication and hard work assisting in the development of this publication. This guide is intended to be consistent with all existing OSHA standards; therefore, if an area is considered by the reader to be inconsistent with a standard, then the OSHA standard should be followed. -

Bill's Cave Diving Lexicon

Bill’s Cave Diving Lexicon 120 Rule: Noticing from the Navy NDL table that, for certain depths, depth + bottom time = 120 so that the NDL can be determined by subtracting the depth from 120. 200 DIN: Thread depth in a DIN valve and associated pressure (200 BAR) that can be handled. This size (7 threads) allows for a DIN to yoke conversion. 300 DIN: Thread depth in a DIN valve that provides the most secure (9 threads) connection and can withstand 300 BAR pressure. 5 nines pure: 99.999% pure, as in a gas. 50-50: Gas mix of 50% oxygen and 50% nitrogen used for decompression gas. 6351-T6 Aluminum Alloy: Alloy that has had problems with tank ruptures. Absolute Pressure: Total pressure being exerted on a diver At sea level Absolute pressure is 1 ATA and it increases by 1 ATA for each 33fsw (34ffw). ADDD (Air, Duration, Depth, Distance): Limits for dive termination acronym minimum Air volume/pressure, maximum Duration of dive, maximum Depth of dive, and maximum Distance of penetration. ADV (Automatic Deflation Valve, and Automatic Diluent Valve ): Device on a buoyancy compensator that allows for rapid air purging, and device on a rebreather that dilutes the breathing mix. AGE (Arterial Gas Embolism): A lung expansion injury. A condition in which gas bubbles enter the arterial system and cause damage by blocking blood flow to vital organs, most commonly the brain. This is generally caused by air passing through the walls of the alveoli into the bloodstream. Air: A gas mixture of Oxygen (21%), Nitrogen (78%), and other gasses (1%, Helium, Argon, etc.). -

Fusion System Components

A Step Change in Military Autonomous Technology Introduction Commercial vs Military AUV operations Typical Military Operation (Man-Portable Class) Fusion System Components User Interface (HMI) Modes of Operation Typical Commercial vs Military AUV (UUV) operations (generalisation) Military Commercial • Intelligence gathering, area survey, reconnaissance, battlespace preparation • Long distance eg pipeline routes, pipeline surveys • Mine countermeasures (MCM), ASW, threat / UXO location and identification • Large areas eg seabed surveys / bathy • Less data, desire for in-mission target recognition and mission adjustment • Large amount of data collected for post-mission analysis • Desire for “hover” ability but often use COTS AUV or adaptations for specific • Predominantly torpedo shaped, require motion to manoeuvre tasks, including hull inspection, payload deployment, sacrificial vehicle • Errors or delays cost money • Errors or delays increase risk • Typical categories: man-portable, lightweight, heavy weight & large vehicle Image courtesy of Subsea Engineering Associates Typical Current Military Operation (Man-Portable Class) Assets Equipment Cost • Survey areas of interest using AUV & identify targets of interest: AUV & Operating Team USD 250k to USD millions • Deploy ROV to perform detailed survey of identified targets: ROV & Operating Team USD 200k to USD 450k • Deploy divers to deal with targets: Dive Team with Nav Aids & USD 25k – USD 100ks Diver Propulsion --------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Low-Frequency Active Towed Sonar

LOW-FREQUENCY ACTIVE TOWED SONAR Full-feature, long-range, low-frequency active and passive variable depth sonar (VDS) The Low-Frequency Active Sonar (LFATS) system is used on ships to detect, track and engage all types of submarines. L3Harris specifically designed the system to perform at a lower operating frequency against modern diesel-electric submarine threats. FEATURES > Compact size - LFATS is a small, > Full 360° coverage - a dual parallel array lightweight, air-transportable, ruggedized configuration and advanced signal system processing achieve instantaneous, > Specifically designed for easy unambiguous left/right target installation on small vessels. discrimination. > Configurable - LFATS can operate in a > Space-saving transmitter tow-body stand-alone configuration or be easily configuration - innovative technology integrated into the ship’s combat system. achieves omnidirectional, large aperture acoustic performance in a compact, > Tactical bistatic and multistatic capability sleek tow-body assembly. - a robust infrastructure permits interoperability with the HELRAS > Reverberation suppression - the unique helicopter dipping sonar and all key transmitter design enables forward, aft, sonobuoys. port and starboard directional LFATS has been successfully deployed on transmission. This capability diverts ships as small as 100 tons. > Highly maneuverable - own-ship noise energy concentration away from reduction processing algorithms, coupled shorelines and landmasses, minimizing with compact twin-line receivers, enable reverb and optimizing target detection. short-scope towing for efficient maneuvering, fast deployment and > Sonar performance prediction - a unencumbered operation in shallow key ingredient to mission planning, water. LFATS computes and displays system detection capability based on modeled > Compact Winch and Handling System or measured environmental data. - an ultrastable structure assures safe, reliable operation in heavy seas and permits manual or console-controlled deployment, retrieval and depth- keeping. -

Sonar for Environmental Monitoring of Marine Renewable Energy Technologies

Sonar for environmental monitoring of marine renewable energy technologies FRANCISCO GEMO ALBINO FRANCISCO UURIE 350-16L ISSN 0349-8352 Division of Electricity Department of Engineering Sciences Licentiate Thesis Uppsala, 2016 Abstract Human exploration of the world oceans is ever increasing as conventional in- dustries grow and new industries emerge. A new emerging and fast-growing industry is the marine renewable energy. The last decades have been charac- terized by an accentuated development rate of technologies that can convert the energy contained in stream flows, waves, wind and tides. This growth ben- efits from the fact that society has become notably aware of the well-being of the environment we all live in. This brings a human desire to implement tech- nologies which cope better with the natural environment. Yet, this environ- mental awareness may also pose difficulties in approving new renewable en- ergy projects such as offshore wind, wave and tidal energy farms. Lessons that have been learned is that lack of consistent environmental data can become an impasse when consenting permits for testing and deployments marine renew- able energy technologies. An example is the European Union in which a ma- jority of the member states requires rigorous environmental monitoring pro- grams to be in place when marine renewable energy technologies are commis- sioned and decommissioned. To satisfy such high demands and to simultane- ously boost the marine renewable sector, long-term environmental monitoring framework that gathers multi-variable data are needed to keep providing data to technology developers, operators as well as to the general public. Technol- ogies based on active acoustics might be the most advanced tools to monitor the subsea environment around marine manmade structures especially in murky and deep waters where divining and conventional technologies are both costly and risky. -

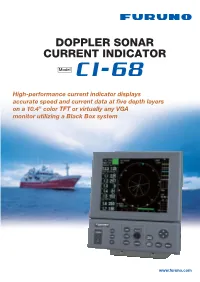

Doppler Sonar Current Indicator 8

DOPPLER SONAR CURRENT INDICATOR 8 Model High-performance current indicator displays accurate speed and current data at five depth layers on a 10.4" color TFT or virtually any VGA monitor utilizing a Black Box system www.furuno.com Obtain highly accurate water current measurements using FURUNO’s reliable acoustic technology. The FURUNO CI-68 is a Doppler Sonar Current The absolute movements of tide Indicator designed for various types of fish and measuring layers are displayed in colors. hydrographic survey vessels. The CI-68 displays tide speed and direction at five depth layers and ship’s speed on a high defi- nition 10.4” color LCD. Using this information, you can predict net shape and plan when to throw your net. Tide vector for Layer 1 The CI-68 has a triple-beam emission system for providing highly accurate current measurement. This system greatly reduces the effects of the Tide vector for Layer 2 rolling, pitching and heaving motions, providing a continuous display of tide information. When ground (bottom) reference is not available Tide vector for Layer 3 acoustically in deep water, the CI-68 can provide true tide current information by receiving position and speed data from a GPS navigator and head- ing data from the satellite (GPS) compass SC- 50/110 or gyrocompass. In addition, navigation Tide vector for Layer 4 information, including position, course and ship ’s track, can also be displayed The CI-68 consists of a display unit, processor Tide vector for Layer 5 unit and transducer. The control unit and display unit can be installed separately for flexible instal- lation. -

Morgan County Emergency and Rescue Squad, Inc

Morgan County Emergency And Rescue Squad, Inc. Standard Operating Guidelines Adopted 6/18/2009 Morgan County Emergency Rescue Squad Standard Operating Guidelines Section 1 – General Guidelines 1 Mission Statement For which this corporation is organized include, but are not limited to the establishment of an organization of members equipped to render fast and effective rescue aid in any and all types of emergency situations including natural and man- made disasters in which it is called on, or is reported to, or which it discovers itself through the diligence of its members. Such situations include, but are not limited to floods, tornados, earthquakes, cave-ins, automobile accidents, airplane crashes, lost or trapped individuals, drownings, and any other natural or man- made disasters. The further purposes are training and emergency operations and first aid. 1.1 Purpose 1.1.1 The Morgan Co Emergency Rescue Squad (MCERS) Department Guidelines: The purpose of these guidelines is to ensure that all operations under the auspices of the MCERS are conducted in a manner that maximizes protection of department members from accidental injury and/or illness. The purpose of this document is to set forth minimal guidelines for the MCERS and to establish the basic regulations and procedures for safety within the MCERS. 1.1.2 These MCERS guidelines and procedures have been developed and are to be implemented to enable the department to meet the requirements of local, state, and federal laws. The MCERS guidelines shall include but not be limited to each mode of operation in which the department is engaged. The guidelines will provide for safety procedures and the responsibilities of the department members for the operation. -

2020 Product Guide Sealife’S Easiest and Most TM Advanced Camera

2020 Product Guide SeaLife’s easiest and most TM advanced camera 3.0 TM Item SL550 The compact Micro 3.0 makes it easier than ever to capture stunning underwater photos and video. Since the camera is sealed, there are no O-rings to maintain and no possible leaks to worry about. The Easy Setup mode ensures the camera is set properly. The three wide “Piano Keys” and a large shutter button make it easy to control all camera functions so you can capture high resolution 16mp still images or record 4K Ultra-HD video with a single touch. The Micro 3.0 has three color correcting underwater scene modes plus Manual white balance to fine tune colors in all conditions. Rugged, compact design with no doors or openings Features Permanently sealed: no O-rings to maintain 16 megapixel SONY® image sensor for sharp colorful images 260K hi-res 2.4” TFT color LCD 4K Ultra HD Video @ 30fps and 1080p HD video @ 120fps Five Land & Sea™ scene modes with color correction The Micro 3.0 advanced features include the ability to Wireless downloading with SeaLife Micro 3.0+ App shoot RAW images with virtually no shutter lag and rapid-fire Three built-in underwater color correction filters burst mode at 10 frames per second for fast moving subjects. The high-capacity battery lasts three hours or more 100° Ultra-Wide Angle Lens fits everything in the shot on a single charge. Use the Micro 3+ app to download RAW/JPEG image format: JPEG & DNG still image files photos/videos to your smartphone or tablet.