Polish Vol. 7 2019 Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (7MB)

British Technologies and Polish Economic Development 1815-1863 Simon Niziol Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy London School of Economics and Political Science University of London December 1995 UMI Number: U084454 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U084454 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 "Theses . F 9555 . 12586 2-5 Abstract After the restoration of peace in 1815, several European countries sought to transform their economies by the direct borrowing of British technologies. One of these was the semi- autonomous Kingdom of Poland. The Kingdom's technology transfer initiatives have been largely ignored by foreign researchers, while Polish historians have failed to place developments in the Kingdom within a wider context of European followership. The varying fortunes of Polish transfer initiatives offer valuable insights into the mechanisms and constraints of the transfer process. A close study of attempts to introduce British technologies in mechanical engineering, metallurgy, railway construction, textile production and agriculture contradicts most Polish scholarship by establishing that most of the transfer initiatives were either misplaced or at least premature. -

(Zamość, Polska) Ikonografia Jana Zamoyskiego

Izabela Winiewicz-Cybulska (Zamość, Polska) Ikonografia Jana Zamoyskiego Sztuka, pełniąc na przestrzeni dziejów różnorodne funkcje, była zwykle dobrym środkiem politycznej propagandy. Szczególną rolę odgrywał portret, który upamiętniając postać wielkiego wodza, polityka czy mecenasa sztuki, zwykle jednoznacznie określał pozycję modela. Wizerunki - tworzone za życia i po śmierci osoby - były gwarancją wiecznie trwającej sławy. Z czasem tworzyły one galerie przodków, kopiowane i powielane przypominały o świetności rodu, jego ciągłości a przede wszystkim o ważnej pozycji założyciela rodowej potęgi. Tak było w przypadku Jana Zamoyskiego - wielkiego kanclerza i hetmana, wybitnego człowieka epoki odrodzenia. Wówczas właśnie portret uzyskał swoją malarską autonomię, stał się wyrazem renesansowego humani- zmu, uznając indywidualność i świecką godność człowieka. Portrety, tworzone dla celów urzędowo- reprezentacyjnych, służyły jako dary w stosunkach dyplomatycznych. Ich prawdziwość była zawsze niewątpliwą zaletą, lecz czasem - w celu szczególnego podkreślenia społecznej i ekonomicznej pozycji portretowanego - heroizowano je - pokazywano poważną twarz, sztywną i władczą pozę. Całość uzupełniano też elementami heraldycznymi, epigraficz-nymi, a nawet alegorycznymi i symbolicznymi. Poziom artystyczny takich wizerunków był zróżnicowany - zależny od tego, czy ich twórca to artysta mający gruntowne przygotowanie, czy jedynie tylko jakiś wrodzony talent i zmysł obserwacji. Należy też pamiętać, że autor musiał liczyć się często z zaleceniami i uwagami samego zleceniodawcy. Najstarsze wizerunki Jana Zamoyskiego, zwłaszcza w grafice i w numizmatach, świadczą niewątpliwie, iż sztuka była narzędziem propagandy. Portrety wykorzystywane do celów politycznych były wizualizacją majestatu portretowanego, jasno określały jego pozycję i szczególne miejsce w zhierarchizowanym ówczesnym społeczeństwie. Takie podkreślenie prestiżu czytelne było dla odbiorców tych dzieł sztuki, a samemu portretowanemu dawało wewnętrzne zadowolenie, umocnienie własnej pozycji i gwarancję wiecznie trwającej sławy. -

Wryly Noted-Books About Books John D

Against the Grain Volume 29 | Issue 6 Article 22 December 2017 Wryly Noted-Books About Books John D. Riley Gabriel Books, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/atg Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Riley, John D. (2017) "Wryly Noted-Books About Books," Against the Grain: Vol. 29: Iss. 6, Article 22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.7886 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Wryly Noted — Books About Books Column Editor: John D. Riley (Against the Grain Contributor and Owner, Gabriel Books) <[email protected]> https://www.facebook.com/Gabriel-Books-121098841238921/ Paper: Paging Through History by Mark Kurlansky. (ISBN: 978-0-393-23961-4, thanks to the development of an ingenious W. W. Norton, New York 2016.) device: a water-powered drop hammer.” An- other Fabriano invention was the wire mold for laying paper. “Fine wire mesh laid paper came his book is not only a history of paper, ample room to wander into Aztec paper making to define European paper. Another pivotal but equally, of written language, draw- or artisan one vat fine paper making in Japan. innovation in Fabriano was the watermark. Ting, and printing. It is about the cultural Another trademark of Kurlansky’s is a Now the paper maker could ‘sign’ his work.” and historical impact of paper and how it has pointed sense of humor. When some groups The smell from paper mills has always been central to our history for thousands of advocated switching to more electronic formats been pungent, due to the use of old, dirty rags years. -

Changes in Print Paper During the 19Th Century

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Charleston Library Conference Changes in Print Paper During the 19th Century AJ Valente Paper Antiquities, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/charleston An indexed, print copy of the Proceedings is also available for purchase at: http://www.thepress.purdue.edu/series/charleston. You may also be interested in the new series, Charleston Insights in Library, Archival, and Information Sciences. Find out more at: http://www.thepress.purdue.edu/series/charleston-insights-library-archival- and-information-sciences. AJ Valente, "Changes in Print Paper During the 19th Century" (2010). Proceedings of the Charleston Library Conference. http://dx.doi.org/10.5703/1288284314836 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. CHANGES IN PRINT PAPER DURING THE 19TH CENTURY AJ Valente, ([email protected]), President, Paper Antiquities When the first paper mill in America, the Rittenhouse Mill, was built, Western European nations and city-states had been making paper from linen rags for nearly five hundred years. In a poem written about the Rittenhouse Mill in 1696 by John Holme it is said, “Kind friend, when they old shift is rent, Let it to the paper mill be sent.” Today we look back and can’t remember a time when paper wasn’t made from wood-pulp. Seems that somewhere along the way everything changed, and in that respect the 19th Century holds a unique place in history. The basic kinds of paper made during the 1800s were rag, straw, manila, and wood pulp. -

1. S. Envelopes by Edward H

THE PROOFS a n d ESSAYS FOR 1. S. ENVELOPES BY EDWARD H. MASON, BOSTON Ί / AS ORIGINALLY PRINTED IN THE PHILATELIC GAZETTE, NEW YORK NEW YORK 19Π« J. M. BARTELS CO., PUBLISHERS 99 NASSAU STREET THE Г ROO E S AND ESSAYS FOR U. S. ENVELOPES. By Edward Η. M ason. Tile writer believes that no list of either the proofs or essays for United States En velopes has ever been attempted, ile has therefore included both and also “trial colors" in the following list. The list includes all of which the writer has been able to learn, but there may be many others. The numbers given· of heads, knives and watermarks are according to the catalogue of J. M. Bartels Co., except in case of en velopes bearing the watermark of a Nesbitt issue. The Bartels catalogue recognizes only one watermark for the Nesbitt issue (No. 1) ; Mr. George L. Toppan in hts catalogue for the Scott Stamp and Coin Co., recognizes eight varieties (Nos. A l to A8) of this watermark, following the list of Messrs. Tiffany, Bogért & Reehert, which recognizes seven varieties. In the following list the varieties of Nesbitt watermarks are designated according to the Toppan list: No. 1. Six Cents, Nesbitt Die No. 6, 1853, on the earliest form of watermarked paper, No. A l. These are die proofs, on horizontally laid paper, and not the reprints of 1861 ( ? ) , which are on vertically laid paper. On slips of paper. (a) Six Cents, green, on white and buff. (b) Six Cents, red, on buff. No. -

Volume 19, Year 2015, Issue 2

Volume 19, Year 2015, Issue 2 PAPER HISTORY Journal of the International Association of Paper Historians Zeitschrift der Internationalen Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Papierhistoriker Revue de l’Association Internationale des Historiens du Papier ISSN 0250-8338 www.paperhistory.org PAPER HISTORY, Volume 19, Year 2015, Issue 2 International Association of Paper Historians Contents / Inhalt / Contenu Internationale Arbeitsgemeinschaft derPapierhistoriker Dear members of IPH 3 Association Internationale des Historiens du Papier Liebe Mitglieder der IPH, 4 Chers membres de l’IPH, 5 Making the Invisible Visible 6 Paper and the history of printing 14 Preservation in the Tropics: Preventive Conservation and the Search for Sustainable ISO Conservation Material 23 Meetings, conferences, seminars, courses and events 27 Complete your paper historical library! 27 Ergänzen Sie Ihre papierhistorische Bibliothek! 27 Completez votre bibliothèque de l’Histoire du papier! 27 www.paperhistory.org 28 Editor Anna-Grethe Rischel Denmark Co-editors IPH-Delegates Maria Del Carmen Hidalgo Brinquis Spain Dr. Claire Bustarret France Prof. Dr. Alan Crocker United Kingdom Dr. Józef Dąbrowski Poland Jos De Gelas Belgium Elaine Koretsky Deadline for contributions each year1.April and USA 1. September Paola Munafò Italy President Anna-Grethe Rischel Präsident Stenhoejgaardsvej 57 Dr. Henk J. Porck President DK- 3460 Birkeroed The Netherlands Denmark Dr. Maria José Ferreira dos Santos tel + 45 45 81 68 03 Portugal +45 24 60 28 60 [email protected] Kari Greve Norway Secretary -

Paper Used for United States Stamps

By Paper Used For Version 1.0 Bill Weiss United States Stamps 2/12/2014 One area that seems to confuse most beginning or novice collectors is paper identification. While catalogs generally provide a brief explanation of different paper types, only the major types are included in catalog Introductions, often no detailed explanations are given, and many of the types found are only mentioned in the Introduction to the category area, ie; paper used for Revenue stamps are listed there. This article will attempt to cover all of the various papers used to print United States stamps and present them in the order that we find them in the catalogs, by Issue. We believe that way of describing them may be more useful to readers then to simply list them in alpha order, for example. UNDERSTANDING DIFFERENCE BETWEEN “HARD” AND “SOFT” WOVE PAPER Wove paper is made by forming the pulp upon a wire cloth and when this cloth is of a closely-woven nature, it produces a sheet of paper which is of uniform texture. Wove paper is further defined as being either “hard” or “soft”. Because there is a difference in the value or identification of some U.S. stamps when printed on both hard and soft paper, it is therefore very important that you can tell them apart. Pre-1877 regular-issue U.S. stamps were all printed on hard paper, but beginning about 1877 Continental Bank Note Company, who held the postage stamp contract at that time, began to use a softer paper, which was then continued when the 1879 consolidation of companies resulted in the American Banknote Company holding the contract. -

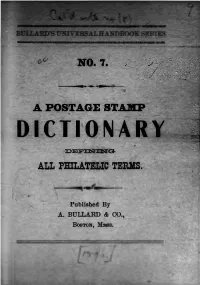

DICTIONARY К D E P in in G L·

NO. 7. A POSTAGE STAMP DICTIONARY к D E P IN IN G l· ALL PHILATELIC TERMS. Published By A. BULLARD & 0 0 ., B oston, Mm s . / II A STAMP DICTIONARY, D efining all T erms used Ą mokg P hilatelists. ("adj.” Ы for “adjective and “ v. pp.” for "verb, puirt participle.") — A— Adhesive, Any stamp that can be glued to an envelope. It may or may not contili» a coating of gum on the back. Advanced collector. (1) A collector of many varieties of postage stamps, or (2) A collector who makes an intelligent study of certain varie ties. Agriculture. An official stamp formerly used by * the Agricultural department of the U. S. Albino. A stamp devoid of color, exhibiting but· a faint impress of the plate from which it was engraved. ' — B— Batonne, A kind of paper in which almost trans parent lines may be discerned by holding to the light. These lines, however, are farther apart than in ordinary laid paper, and may be used as guide lines in writing. Between these lines the ifexture of the paper may be either wove or laid. It is called “foreign note paper” by the English. Also see Laid paper. Bisected stamp. See Split stamp. Block. Four stamps cut from the same sheet, so placed as to resemble a square, and left unde tached from one another. Bogus stamps. Either ( 1) counterfeits, or (2) stamps which were neveF intended for postal use. Sêe counterfeits. British Coloniale. Stamps used in any part of the colonies belonging to Great Britain. Example, stamps of Victoria. -

Aneta Kiper Anglicy W Ordynacji Zamoyskiej W XIX Wieku

Aneta Kiper Anglicy w Ordynacji Zamoyskiej w XIX wieku Rocznik Kolbuszowski 12, 7-86 2012 Anglicy w Ordynacji Zamoyskiej w XIX wieku 7 ANETA KIPER – Lublin Anglicy w Ordynacji Zamoyskiej w XIX wieku1 Sprawami Ordynacji Zamoyskiej zajmowało się wielu hi- storyków. Ich zainteresowania najczęściej jednak skupiały się na jej wcześniejszych dziejach. Do tej pory tymczasem nie powstała żadna monografia, która byłaby poświęcona działalności Anglików w Ordynacji Zamoyskiej. Celem tej pracy natomiast było ukazanie społeczności angielskiej znajdującej się w dobrach Zamoyskich, przedstawienie motywów ich przybycia do ordynacji i przyczyn, dla których byli tam zatrudniani oraz ich relacji z władzami. Omówio- ny został również ich wpływ na rozwój gospodarczy w ordynacji. Wskazano, jakie stanowiska zajmowali i w jakim stopniu spełnili oczekiwania Zamoyskich. Ponadto interesującą rzeczą były ich wza- jemne relacje oraz różnice między nimi w umiejętności prowadzenia powierzonych im folwarków i zakładów. W pracy tej przedstawi- łam działalność Anglików w Ordynacji Zamoyskiej znajdującej się w granicach Królestwa Polskiego. Nie uwzględniłam natomiast tych niewielkich dóbr położonych w Galicji. Ramy chronologiczne obejmują lata 1804-1870. Data począt- kowa jest związana z podpisaniem przez Stanisława Zamoyskiego umowy z Janem Mac Donaldem, na mocy której jako pierwszy Anglik miał on pracować w ordynacji. Rok 1870 natomiast jest to rok rozwiązania umowy o folwarki z Campbellem. Po tej dacie nie znalazłam żadnych wzmianek o Anglikach, którzy pracowaliby w dobrach Zamoyskich. Mianem ordynacji określano instytucję prawną zapewniającą niezmienność posiadania dóbr ziemskich przez ten sam ród. Była to także nazwa posiadłości objętych przepisami ordynacji rodowej, 1 Praca magisterska napisana na seminarium w Instytucie Historii Wydziału Nauk Humanistycznych Katolickiego Uniwersytetu Lubelskiego w Lublinie pod kierownictwem prof. -

Recycling Paper for Nonpaper Uses

Recycling Paper for Nonpaper Uses Brent W. English, Industrial Specialist USDA Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory One Gifford Pinchot Drive Madison, WI 53705-2366 November 1993 Prepared for Presentation at American Institute of Chemical Engineers Annual Meeting, Forest Products Division, November 7-12, 1993. St. Louis, Missouri. Session 131: Advances in Wood Production and Preparation-Raw Materials Keywords: Wood fiber, composites, municipal solid waste, wastepaper, waste wood, waste plastic, biomass fibers, processing, properties, economics, inorganic binders The Forest Products Laboratory is maintained in cooperation with the University of Wisconsin. This article was written and prepared by U.S. Government employees on official time, and it is therefore in the public domain and not subject to copyright. ABSTRACT The largest components of the municipal solid waste stream are paper and paper products. Paper comes in many grades and from many sources. A significant portion of wastepaper is readily identifiable and can be easily sorted and collected for recycling into paper products. Old newspapers, office paper, and old corrugated containers are examples of these identifiable paper types. An even greater portion of wastepaper is not easily sorted and collected: this portion includes packaging, plastic coated paper, and mixed paper. In addition, many forms of wastepaper contain contaminants such as adhesives, inks, dyes, metal foils, plastics, or ordinary household wastes. These contaminants must be separated from the wastepaper before the fiber can be recycled into paper products. This is not the case when recycling into wood-based composites. In many uses, wood-based composites are opaque, colored, painted, or overlaid. Consequently, wastepaper for recycling into composites does not require extensive cleaning and refinement. -

Laid Paper Mold-Mate Identification Via Chain Line

1 Laid Paper Mold-Mate Identification via Chain Line Pattern (CLiP) Matching of Beta-Radiographs of Rembrandt's Etchings C. Richard Johnson, Jr. :: Cornell University / Rijksmuseum William A. Sethares :: University of Wisconsin Margaret Holben Ellis :: New York University / The Morgan Library & Museum Reba Snyder :: The Morgan Library & Museum Erik Hinterding :: Rijksmuseum Idelette van Leeuwen :: Rijksmuseum Arie Wallert :: Rijksmuseum Dionysia Christoforou :: Rijksmuseum Jan van der Lubbe :: Technische Universiteit Delft July 2013 Summary This document describes a project { initiated late in 2012 { to use the chain line patterns apparent in beta-radiographs of the prints of Rembrandt to help identify mold-mates, i.e. pa- pers made from the same mold, among those prints lacking watermarks. Background An ultimate objective of technical examination of laid papers is to help determine their date and location of manufacture. Prior to the mid-18th century laid papers were made by scooping paper pulp with a mold comprised of a screen within a rectangular wooden frame (Hunter, 1978) (Loeber, 1982). The screen allowed the water to drain from the pulp leaving a sheet of paper { sized by the borders of the frame { that would be removed to dry. The mold-based procedure for producing laid papers described in (Hunter, 1978) and (Loeber, 1982), leaves impressed features, including chain and laid lines and watermarks, detectable as thinner locations on a sheet of paper. Transmitted light photographs and beta-radiographs are often proposed for revealing these impressions as the thinner portions of the paper impede the signal less and therefore stand out in the image produced. Transmitted light photographs have the disadvantage that the printed image also impedes the received signal thereby obscuring the chain line indentations. -

Zarys Stanu I Problematyki Polskich Badań Nad Naczyniami Szklanymi Z Xiv–Xviii Wieku W Latach 1987–2018

Archeologia Polski, LXV: 2020 PL ISSN 0003-8180 DOI: 10.23858/APol65.2020.007 MAGDALENA BISa ZARYS STANU I PROBLEMATYKI POLSKICH BADAŃ NAD NACZYNIAMI SZKLANYMI Z XIV–XVIII WIEKU W LATACH 1987–2018 A SUMMARY OF THE STATE OF THE POLISH RESEARCH INTO GLASS VESSELS FROM THE 14TH–18TH CENTURIES CARRIED OUT IN THE YEARS 1987–2018 AND THE OUTLINE OF KEY RESEARCH PROBLEMS Abstrakt: Przedmiotem artykułu są naczynia szklane będące znaleziskami archeologicznymi, datowane na okres późnego średniowiecza i czasów nowożytnych, uwzględnione w polskich publi- kacjach z lat 1987–2018. Są to głównie opracowania archeologiczne, ale również istotne w bada- niach nad tymi wyrobami studia z zakresu historii, historii sztuki, chemii i konserwatorstwa. Celem autorki było zebranie dotychczas upowszechnionego zasobu tej kategorii źródeł z obszaru współczesnej Polski, omówienie sposobu ich prezentacji, określenie miejsc pozyskania, liczebności i zawartości zbiorów. Wskazane zostały też zagadnienia podejmowane dotychczas przez badaczy, zarówno te rozwiązane, jak i niedostatecznie poznane, wymagające dalszych studiów. Słowa kluczowe: wyroby szklane, naczynia szklane, studia nad szkłem, późne średniowiecze, nowożytność, stan badań, zabytki archeologiczne Abstract: Author presents glass vessels discovered through archaeological works, dated to the late medieval, post-medieval and early modern period, that are described in available Polish publications from the years 1987–2018. These are mainly archaeological publications, but also studies in history, art history, chemistry, and conservation that are relevant in the research into the above-mentioned products. The aim of the author was to collect and present in one paper information about this category of archaeological sources from the area of contemporary Poland published so far, discuss the possibilities and limitations of describing those artefacts, establish the place of discovery, the size and the content of assemblages.