And Siamang (H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gibbon Journal Nr

Gibbon Journal Nr. 5 – May 2009 Gibbon Conservation Alliance ii Gibbon Journal Nr. 5 – 2009 Impressum Gibbon Journal 5, May 2009 ISSN 1661-707X Publisher: Gibbon Conservation Alliance, Zürich, Switzerland http://www.gibbonconservation.org Editor: Thomas Geissmann, Anthropological Institute, University Zürich-Irchel, Universitätstrasse 190, CH–8057 Zürich, Switzerland. E-mail: [email protected] Editorial Assistants: Natasha Arora and Andrea von Allmen Cover legend Western hoolock gibbon (Hoolock hoolock), adult female, Yangon Zoo, Myanmar, 22 Nov. 2008. Photo: Thomas Geissmann. – Westlicher Hulock (Hoolock hoolock), erwachsenes Weibchen, Yangon Zoo, Myanmar, 22. Nov. 2008. Foto: Thomas Geissmann. ©2009 Gibbon Conservation Alliance, Switzerland, www.gibbonconservation.org Gibbon Journal Nr. 5 – 2009 iii GCA Contents / Inhalt Impressum......................................................................................................................................................................... i Instructions for authors................................................................................................................................................... iv Gabriella’s gibbon Simon M. Cutting .................................................................................................................................................1 Hoolock gibbon and biodiversity survey and training in southern Rakhine Yoma, Myanmar Thomas Geissmann, Mark Grindley, Frank Momberg, Ngwe Lwin, and Saw Moses .....................................4 -

10 Sota3 Chapter 7 REV11

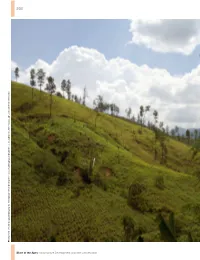

200 Until recently, quantifying rates of tropical forest destruction was challenging and laborious. © Jabruson 2017 (www.jabruson.photoshelter.com) forest quantifying rates of tropical Until recently, Photo: State of the Apes Infrastructure Development and Ape Conservation 201 CHAPTER 7 Mapping Change in Ape Habitats: Forest Status, Loss, Protection and Future Risk Introduction This chapter examines the status of forested habitats used by apes, charismatic species that are almost exclusively forest-dependent. With one exception, the eastern hoolock, all ape species and their subspecies are classi- fied as endangered or critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (IUCN, 2016c). Since apes require access to forested or wooded land- scapes, habitat loss represents a major cause of population decline, as does hunting in these settings (Geissmann, 2007; Hickey et al., 2013; Plumptre et al., 2016b; Stokes et al., 2010; Wich et al., 2008). Until recently, quantifying rates of trop- ical forest destruction was challenging and laborious, requiring advanced technical Chapter 7 Status of Apes 202 skills and the analysis of hundreds of satel- for all ape subspecies (Geissmann, 2007; lite images at a time (Gaveau, Wandono Tranquilli et al., 2012; Wich et al., 2008). and Setiabudi, 2007; LaPorte et al., 2007). In addition, the chapter projects future A new platform, Global Forest Watch habitat loss rates for each subspecies and (GFW), has revolutionized the use of satel- uses these results as one measure of threat lite imagery, enabling the first in-depth to their long-term survival. GFW’s new analysis of changes in forest availability in online forest monitoring and alert system, the ranges of 22 great ape and gibbon spe- entitled Global Land Analysis and Dis- cies, totaling 38 subspecies (GFW, 2014; covery (GLAD) alerts, combines cutting- Hansen et al., 2013; IUCN, 2016c; Max Planck edge algorithms, satellite technology and Insti tute, n.d.-b). -

Gibbon Classification : the Issue of Species and Subspecies

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1988 Gibbon classification : the issue of species and subspecies Erin Lee Osterud Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons, and the Genetics and Genomics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Osterud, Erin Lee, "Gibbon classification : the issue of species and subspecies" (1988). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3925. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5809 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Erin Lee Osterud for the Master of Arts in Anthropology presented July 18, 1988. Title: Gibbon Classification: The Issue of Species and Subspecies. APPROVED BY MEM~ OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Marc R. Feldesman, Chairman Gibbon classification at the species and subspecies levels has been hotly debated for the last 200 years. This thesis explores the reasons for this debate. Authorities agree that siamang, concolor, kloss and hoolock are species, while there is complete lack of agreement on lar, agile, moloch, Mueller's and pileated. The disagreement results from the use and emphasis of different character traits, and from debate on the occurrence and importance of gene flow. GIBBON CLASSIFICATION: THE ISSUE OF SPECIES AND SUBSPECIES by ERIN LEE OSTERUD A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ANTHROPOLOGY Portland State University 1989 TO THE OFFICE OF GRADUATE STUDIES: The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Erin Lee Osterud presented July 18, 1988. -

Nomascus Hainanus) We Conducted a Long-Term Dietary Composition Survey in Bawangling National Nature Reserve, Hainan Island, China from 2002 to 2014

NORTH-WESTERN JOURNAL OF ZOOLOGY 14 (2): 213-219 ©NWJZ, Oradea, Romania, 2018 Article No.: e171703 http://biozoojournals.ro/nwjz/index.html Thirteen years observation on diet composition of Hainan gibbons (Nomascushainanus) Huaiqing DENG and Jiang ZHOU* School of Life Sciences, Guizhou Normal University, Guiyang, Guizhou, 550001, China E-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author, J. Zhou, Tel:+8613985463226, E-mail: [email protected] Received: 08. April 2017 / Accepted: 27. July 2017 / Available online: 27. July 2017 / Printed: December 2018 Abstract. Researches on diets and feeding behavior of endangered species are critical to understand ecological adaptations and develop conservation strategies. To document the diet of the Hainan gibbon (Nomascus hainanus) we conducted a long-term dietary composition survey in Bawangling National Nature Reserve, Hainan Island, China from 2002 to 2014. Transects and quadrants were established to monitor plant phenology and to count tree species. Tracking survey and scan-sampling method were used to record the feeding species and feeding time of Hainan Gibbon. Our results showed that Hainan gibbons’ habitat vegetation structure is tropical montane evergreen forest dominated by Lauraceae species while Dipterocarpaceae, Leguminosae and Ficusare rare. Hainan gibbons consume 133 plant species across 83 genera and 51 families. Hainan gibbons consumed more Lauraceae and Myrtaceae plant species than other plant species, whereas their consumption of leguminous species was little and with no Dipterocarpaceae compared to other gibbons. Furthermore, we classified the food plants as different feeding parts and confirmed that this gibbon species is a main fruits eater particularly during the wet season (114 species,64.8% feeding time), meanwhile we also observed five species of animal foods. -

Sound Spectrum Characteristics of Eastern Black Crested Gibbons

NORTH-WESTERN JOURNAL OF ZOOLOGY 13 (2): 347-351 ©NwjZ, Oradea, Romania, 2017 Article No.: e161705 http://biozoojournals.ro/nwjz/index.html Sound spectrum characteristics of Eastern Black Crested Gibbons Huaiqing DENG#, Huamei WEN# and Jiang ZHOU* School of Life Sciences, Guizhou Normal University, Guiyang, Guizhou, 550001, China, E-mail: [email protected] # These authors contributed to the work equally and regarded as Co-first authors. * Corresponding author, J. Zhou, E-mail: [email protected], Tel.:13985463226 Received: 01. November 2016 / Accepted: 07. September 2016 / Available online: 19. September 2016 / Printed: December 2017 Abstract. Studies about the sound spectrum characteristics and the intergroup differences in eastern black crested gibbon (Nomascus nasutus) song are still rare. Here, we studied the singing behavior of eastern black crested gibbon based on song samples of three groups of gibbons collected from Trung Khanh, northern Vietnam. The results show that: 1) Song frequency of both adult male and adult female eastern black crested gibbon is low and both are below 2 KHz; 2) Songs of adult male eastern black gibbons are composed mainly of short syllables (aa notes) and frequency modulated syllables (FM notes), while adult female gibbons only produce a stable and stereotyped pattern of great calls; 3) There is significant differences among the three groups in highest and lowest frequency of FM syllable in males’ song; 4) The song chorus is dominated by adult males, while females add a great call; 5) The sound spectrum frequency is lower and complex, which is different from Hainan gibbon. The low frequency in the singing of the eastern black crested gibbon is related to the structure and low quality of the vegetation of its habitat. -

Views That Abuse: the Rise of Fake “Animal Rescue” Videos on Youtube Views That Abuse: the Rise of Fake “Animal Contents Rescue” Videos on Youtube

Views that abuse: The rise of fake “animal rescue” videos on YouTube Views that abuse: the rise of fake “animal Contents rescue” videos on YouTube World Animal Protection is registered Foreword 03 with the Charity Commission as a charity and with Companies House as a company limited by guarantee. World Animal Summary 04 Protection is governed by its Articles of Association. Introduction 05 Charity registration number 1081849 Company registration number 4029540 Methods 06 Registered office 222 Gray’s Inn Road, London WC1X 8HB Results 07 Main findings 12 Animal welfare 13 Conservation concern 13 How to spot a fake animal rescue 14 YouTube policy 15 Call to action 15 References 16 2 Views that abuse: the rise of fake “animal rescue” videos on YouTube Image: A Lar gibbon desperately tries to break free from the grip of a Reticulated python in footage from a fake “animal rescue” video posted on YouTube. The Endangered Lar gibbon is just one of many species of high conservation concern being targeted in these videos. The use of these species, even in small numbers, could have damaging impacts on the survival of remaining populations. Foreword Social media is ubiquitous. There were an estimated 3.6 warn its users about the harm of taking irresponsible photos billion social media users worldwide in 2020 representing including those with captive wild animals, after hundreds of approximately half of the world’s population. thousands of people urged for the social media giant to act. Hundreds of hours of video content are being uploaded to This new report is timely. -

A White-Cheeked Crested Gibbon Ethogram & a Comparison Between Siamang

A white-cheeked crested gibbon ethogram & A comparison between siamang (Symphalangus syndactylus) and white-cheeked crested gibbon (Nomascus leucogenys) Janet de Vries Juli – November 2004 The gibbon research Lab., Zürich (Zwitserland) Van Hall Instituut, Leeuwarden J. de Vries: Ethogram of the White-Cheeked Crested Gibbon 2 A white-cheeked crested gibbon ethogram A comparison between siamang (Symphalangus syndactylus) and white-cheeked crested gibbon (Nomascus leucogenys) By: Janet de Vries Final project Animal management Projectnumber: 344311 Juli 2004 – November 2004-12-01 Van Hall Institute Supervisor: Thomas Geissmann of the Gibbon Research Lab Supervisors: Marcella Dobbelaar, & Celine Verheijen of Van Hall Institute Keywords: White-cheeked crested gibbon (Nomascus leucogenys), Siamang (Symphalangus syndactylus), ethogram, behaviour elements. J. de Vries: Ethogram of the White-Cheeked Crested Gibbon 3 Preface This project… text missing Janet de Vries Leeuwarden, November 2004 J. de Vries: Ethogram of the White-Cheeked Crested Gibbon 4 Contents Summary ................................................................................................................................ 5 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 6 1.1 Gibbon Ethograms ..................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Goal .......................................................................................................................... -

Age Related Decline in Female Lar Gibbon Great Call Performance Suggests That Call Features Correlate with Physical Condition Thomas A

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Publications Department of Anthropology Spring 2-5-2016 Age related decline in female lar gibbon great call performance suggests that call features correlate with physical condition Thomas A. Terlepht Sacred Heart University, [email protected] Suchinda Malaivijitnond Chulalongkorn University, [email protected] Ulrich H. Reichard Ulrich H Reichard, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/anthro_pubs This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Recommended Citation Terlepht, Thomas A., Malaivijitnond, Suchinda and Reichard, Ulrich H. "Age related decline in female lar gibbon great call performance suggests that call features correlate with physical condition." BMC Evolutionary Biology 16, No. 4 (Spring 2016): 13. doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0578-8. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Anthropology at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Terleph et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2016) 16:4 DOI 10.1186/s12862-015-0578-8 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Age related decline in female lar gibbon great call performance suggests that call features correlate with physical condition Thomas A. Terleph1* , S. Malaivijitnond2,3 and U. H. Reichard4 Abstract Background: White-handed gibbons (Hylobates lar) are small Asian apes known for living in stable territories and producing loud, elaborate vocalizations (songs), often in well-coordinated male/female duets. The female great call, the most conspicuous phrase of the repertoire, has been hypothesized to function in intra-sexual territorial defense. -

THE PRECARIOUS STATUS of the WHITE-HANDED GIBBON Hylobates Lar in LAO PDR Ramesh Boonratana1*, J.W

13 Asian Primates Journal 2(1), 2011 THE PRECARIOUS STATUS OF THE WHITE-HANDED GIBBON Hylobates lar IN LAO PDR Ramesh Boonratana1*, J.W. Duckworth2, Phaivanh Phiapalath3, Jean-Francois Reumaux4, and Chaynoy Sisomphane5 1 Mahidol University International College, Mahidol University, 999 Buddhamonthon 4 Road, Salaya, Nakhon Pathom 73170, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] 2 PO Box 5573, Vientiane, Lao PDR. E-mail: [email protected] 3 International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Ban Watchan, Fa Ngum Road, PO Box 4340, Vientiane, Lao PDR. E-mail: [email protected] 4 PO Box 400, Houayxay, Bokeo, Lao PDR. E-mail: [email protected] 5 Wildlife Section, Division of Forest Resource Conservation, Department of Forestry, Thatdam Road, PO Box 2932, Vientiane, Lao PDR. E-mail: [email protected] * Corresponding author ABSTRACT The White-handed Gibbon Hylobates lar is restricted within Lao PDR to the small portion of the north of the country that lies west of the Mekong River. The evidence-base includes one historical specimen of imprecise provenance, recent records of a few captives (of unknown origin), and a few recent field records. Only one national protected area (NPA), Nam Pouy NPA, lies within its Lao range, and the populations of the species now seem to be small and fragmented. Habitat degradation, conversion and fragmentation, and hunting, are all heavy in recently-surveyed areas, including the NPA. Without specific attention, national extinction is very likely, although the precise level of threat is unclear because so little information is available on its current status in the country. Keywords: conservation, distribution, geographic range, Mekong, threat status INTRODUCTION Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR; Laos) (e.g. -

SILVERY GIBBON PROJECT NEWSLETTER the Page 1 June 2013 SILVERY GIBBON PROJECT

SILVERY GIBBON PROJECT NEWSLETTER The Page 1 June 2013 SILVERY GIBBON PROJECT PO BOX 335 COMO 6952 WESTERN AUSTRALIA Website: www.silvery.org.au E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 0438 992 325 June 2013 PRESIDENT’S REPORT Dear Members and Friends I hope, not just for Sadewa and Kiki, this forest will present an opportunity for many other gibbons Well this is what it’s all about! On June 15 two currently kept at JGC to live as a gibbons should; Javan Gibbon Centre (JGC) residents - Sadewa and for the species, an opportunity to establish a and Kiki - will be free! After years of planning, our new population of gibbons in Java. new release site at Malabar Forest near Bandung has been secured, facilities have been We will keep you posted on their progress. The constructed and the team is ready to go. Sadewa release program, however, has added significant and Kiki have been transferred to their new expenditure to our budget this year and we are enclosure at the release site and are getting used urgently seeking support. If you are able to help to the sights, sounds and tastes of this forest! I with a tax-deductible donation before the end of will have the privilege of being there on June 15 the financial year, we would greatly appreciate it - when their cage door is opened, and I hope that you will be helping to secure a future for Silvery this will symbolize a bright future for Javan gibbon gibbons! conservation. We were so pleased this month to see enthusiastic youngsters in QLD doing their bit to help Silvery gibbons. -

An Assessment of Trade in Gibbons and Orang-Utans in Sumatra, Indoesia

AN ASSESSMENT OF TRADE IN GIBBONS AND ORANG-UTANS IN SUMATRA, INDONESIA VINCENT NIJMAN A TRAFFIC SOUTHEAST ASIA REPORT Published by TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia © 2009 TRAFFIC Southeast Asia All rights reserved. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC Southeast Asia as the copyright owner. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC Network, WWF or IUCN. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. Layout by Noorainie Awang Anak, TRAFFIC Southeast Asia Suggested citation: Vincent Nijman (2009). An assessment of trade in gibbons and orang-utans in Sumatra, Indonesia TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia ISBN 9789833393244 Cover: A Sumatran Orang-utan, confiscated in Aceh, stares through the bars of its cage Photograph credit: Chris R. Shepherd/TRAFFIC Southeast Asia An assessment of trade in gibbons and orang-utans in Sumatra, Indonesia Vincent Nijman Cho-fui Yang Martinez -

Traffic Southeast Asia Report

HANGING IN THE BALANCE: AN ASSESSMENT OF TRADE IN ORANG-UTANS AND GIBBONS ON KALIMANTAN,INDONESIA VINCENT NIJMAN A TRAFFIC SOUTHEAST ASIA REPORT TRAFFIC SOUTHEAST ASIA Published by TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia © 2005 TRAFFIC Southeast Asia All rights reserved. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be produced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC Southeast Asia as the copyright owner. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC Network, WWF or IUCN. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF, TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. Layout by Noorainie Awang Anak, TRAFFIC Southeast Asia Suggested citation: Vincent Nijman (2005), Hanging in the Balance: An Assessment of trade in Orang-utans and Gibbons in Kalimantan, Indonesia TRAFFIC Southeast Asia ISBN 983-3393-03-9 Photograph credit: Pet Müller’s Gibbon Hylobates muelleri, West Kalimantan, Indonesia (Ian M. Hilman/Yayasan Titian) Hanging in the Balance: An Assessment of Trade in Orang-utans and Gibbons in Kalimantan, Indonesia HANGING IN THE BALANCE: An assessment of trade in orang-utans and gibbons in Kalimantan, Indonesia Vincent Nijman August 2005 Yuyun Kurniawan/Yayasan Titian Kurniawan/Yayasan Yuyun Credit: Credit: Orang-utan and macaque skulls used for decoration in Central Kalimantan.