'The Codex Wintoniensis and the King's Haligdom'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black House Farm, Hinton Ampner, Hampshire February 2018

Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment in Advance of the Proposed development of Land at Black House Farm, Hinton Ampner, Hampshire February 2018 Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment in Advance of the Proposed development of land at Black House Farm, Hinton Ampner, Hampshire. Report for Nadim Khatter Date of Report: 20th February 2018 SWAT ARCHAEOLOGY Swale and Thames Archaeological Survey Company School Farm Oast, Graveney Road Faversham, Kent ME13 8UP Tel; 01795 532548 or 07885 700 112 www.swatarchaeology.co.uk Black House Farm, Hinton Ampner, Hampshire Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment Contents 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Project Background ......................................................................................... 4 1.2 The Site ............................................................................................................ 4 1.3 The Proposed Development............................................................................ 4 1.4 Project Constraints .......................................................................................... 5 1.5 Scope of Document ......................................................................................... 5 2 PLANNING BACKGROUND .................................................................................................. 5 2.1 Introduction..................................................................................................... 5 2.2 -

South Downs National Park Gypsy

South Downs National Park: Gypsy, Traveller and Travelling Showpeople Background Paper (2016) South Downs National Park Gypsy, Traveller and Travelling Showpeople Background Paper 2016: APPENDIX A - G Base date 1st DECEMBER 2016 (This study does not currently include the Brighton & Hove City area) 0 South Downs National Park: Gypsy, Traveller and Travelling Showpeople Background Paper (2016) Appendix A: Existing provision of Gypsy and Traveller sites with the SDNP at 1st December 2016 i) Current Authorised Gypsy & Traveller Pitches Ref Local Parish / Ward Permanent Temporary Ownership Authority AR(GT)02 Wychway Farm, Patching Arun Patching 1 0 Private AR(GT)03 Forest View Park, Crossbush Arun Poling 12 0 Private AR(GT)04 The Wood Yard, Patching Arun Patching 1 0 Private AR(GT)05 Coventry Plantation, Findon Arun Findon 7 0 Private AR(GT)06 Old Timbers, Slindon Common Arun Slindon 1 0 Private AR(GT)07 Savi Maski Granzi Stable Yard, Arun Findon 1 0 Private Findon BH(GT)29 Horsdean Traveller Site, Patcham Brighton & Patcham 12 0 Local Hove Authority C(GT)01 Oak Tree Farm Stables, Kirdford Chichester Kirdford 1 0 Private EH(GT)01 Fern Farm, Greatham East Hants Greatham 0 2 Private EH(GT)03 Half Acre, Hawkley East Hants Hawkley 0 5 caravans (approx. Private 3 pitches) EH(GT)04 New Barn Stables, Binsted East Hants Binstead 1 0 Private L(GT)01 Adjacent to Offham Filling Station, Lewes Hamsey 4 0 Private Offham L(GT)02 The Pump House, Kingston nr Lewes Lewes Kingston 0 1 Private MS(GT)01 Market Gardens Caravan, Fulking Mid Sussex Fulking 1 0 Private -

Shroner Barn Martyr Worthy • Winchester • Hampshire

Shroner Barn Martyr Worthy • Winchester • Hampshire Shroner Barn Basingstoke Road • Martyr Worthy • Winchester • Hampshire • SO21 1AG A detached family home with well-presented accommodation, set within delightful grounds of 1.3 acres and with fabulous views over neighbouring countryside Accommodation Sitting room • Dining room • Study • Kitchen/breakfast room • Laundry/utility room • Shower room Principal bedroom with en suite • Guest bedroom with en suite • 2 further bedrooms • Jack & Jill bathroom External store • Gardens In all about 1.3 acres EPC = D SaviIls Winchester 1 Jewry Street, Winchester, SO23 8RZ [email protected] 01962 841 842 Situation Description Martyr Worthy is a delightful rural village situated to the east of Shroner Barn is a sympathetic and attractively converted barn which A large dining/garden room with central fireplace really does interact Winchester in the heart of the Itchen Valley. It is an exceptional had significant input from the renowned local architect Huw Thomas. well with the external environment and enjoys a fantastic outlook over location for access to central Winchester which offers a superb range This fine property has undergone significant improvement with the the grounds and countryside beyond, an excellent reception space. of amenities as well as renowned schooling including Winchester current owners resulting in a quite fantastic living environment. The At first floor there are a total of four bedrooms including a principal College, St Swithun’s School and Peter Symonds Sixth Form College. open plan kitchen/breakfast/family room is a magnificent living space, bedroom with en suite and a further guest suite with en suite facilities. Preparatory education can be found at Prince’s Mead in Abbots a recently fitted kitchen makes a real impact with an impressive The remaining bedrooms are serviced by a Jack and Jill bathroom. -

Candidates in the New Upper Meon Valley Ward

Caring and campaigning for our community WINCHESTER CITY COUNCIL ELECTIONS MAY 5TH Your priorities are our priorities We will be accessible, approachable and visible in your local 1 communities, listening to you, championing your concerns. We will continue to work with your parish and county councillors, 2 and with the local MP, to achieve the best outcomes on issues in CANDIDATES IN THE NEW the new Upper Meon Valley ward. We will work to ensure that flood management and prevention is UPPER MEON VALLEY WARD 3 given the highest priority by the County and City authorities. We will work to conserve and enhance the landscape and 4 character, to develop the green infrastructure of our beautiful LAURENCE RUFFELL AMBER THACKER villages, and to protect and enhance the habitats of our wild species. Michael Lane for Police Commissioner My priority will always be to keep technology & intelligence to stay you and your family safe. My ahead of criminals and free up policing plan and budget will police time for front-line work. empower the Chief Constable My military background, business and our police to do what they do experience and community service best – prevent crime and catch as a Councillor, all equip me to criminals. bring the necessary leadership to I will spare no effort to ensure we take the tough decisions that will are efficient and focussed on what be needed. matters most to communities. I am asking for your support to I will drive improvement in I have been a Winchester City Councillor for This year has been an exciting and fulfilling GCA 167 Stoke Road, Gosport, PO12 1SE PO12 Gosport, Road, Stoke 167 GCA Promoted by Alan Scard on behalf of Michael Lane of of Lane Michael of behalf on Scard Alan by Promoted make Hampshire safer. -

Unit 4 Bridgets Farm Offices Bridgets Lane, Martyr Worthy, Hampshire SO21 1AR

Unit 4 Bridgets Farm Offices Bridgets Lane, Martyr Worthy, Hampshire SO21 1AR Office Unit to Rent Parking Office- 32.01 sqm (344 sq ft) Store - 4.28 sqm (46 sq ft) £6,000 pa (£500 pcm) 01962 763900 www.bcm.co.uk Unit 4 Bridgets Farm Offices - Bridgets Lane, Martyr Worthy, Hampshire SO21 1AR Self contained office unit in a rural location near to the village of Martyr Worthy, only a short distance from Winchester. Available on a new lease with flexible terms and available now. Ample parking. DESCRIPTION LEGAL COSTS The office is located about 1 mile from the village of Martyr Worthy, Each party will be responsible for their own legal costs incurred. 2 miles from Itchen Abbas and 3.5 miles to junction 9 of the M3 offering excellent road access beyond. VIEWING Strictly by appointment with BCM. GENERALLY Tel: 01962 763900 E: [email protected] Unit 4 Bridgets Farm benefits from plenty of parking, a spacious office area, modern kitchen, WC including disabled facilities and a DIRECTIONS useful storage area. There is an oil-fired boiler for heating and hot From Winchester and Junction 9 of the M3 water and an electric air conditioning system. The store room Take A33 towards Basingstoke. After 1.4 miles turn right onto B3047 measuring 46 sq ft contains shelving to maximise storage. The signed to Alresford, Itchen Abbas and Itchen Stoke. After 1.4 miles turn left premises has modern lighting and CAT 5 cabling. into Bridgets Lane opposite the war memorial. After 3/4 mile Bridgets Farm offices are on the left hand side. -

Depositing Archaeological Archives

Hampshire County Council Arts & Museums Service Archaeology Section Depositing Archaeological Archives Version 2.3 October 2012 Contents Contact information 1. Notification 2. Transfer of Title 3. Selection, Retention and Disposal 4. Packaging 5. Numbering and Labelling 6. Conservation 7. Documentary Archives 8. Transference of the Archive 9. Publications 10. Storing the Archive. Appendix 1 Archaeology Collections. Appendix 2 Collecting Policy (Archaeology). Appendix 3 Notification and Transfer Form. Appendix 4 Advice on Packaging. Appendix 5 Advice on marking, numbering and labelling. Appendix 6 Advice on presenting the Documentary Archive. Appendix 7 Storage Charge Contact us Dave Allen Keeper of Archaeology Chilcomb House, Chilcomb Lane, Winchester, Hampshire, SO23 8RD. [email protected] Telephone: 01962 826738 Fax: 01962 869836 Location map http://www3.hants.gov.uk/museum/museum-finder/about-museumservice/map- chilcomb.htm Introduction Hampshire County Council Arts & Museums Service (hereafter the HCCAMS) is part of the Culture, Communities & Business Services Department of the County Council. The archaeology stores are located at the Museum headquarters at Chilcomb House, on the outskirts of Winchester, close to the M3 (see above). The museum collections are divided into four main areas, Archaeology, Art, Hampshire History and Natural Sciences. The Archaeology collection is already substantial, and our existing resources are committed to ongoing maintenance and improving accessibility and storage conditions for this material. In common with other services across the country, limited resources impact on our storage capacity. As such, it is important that any new accessions relate to the current collecting policy (Appendix 2). This document sets out the requirements governing the deposition of archaeological archives with the HCCAMS. -

Points of Literary Interest

Points of literary interest East Hampshire has a wealth of literary associations. The “...out we came, all in a moment, at the very edge of the literary walks have been devised to illustrate the work of six hanger! And never, in all my life, was I so surprised and important writers who were close observers of their natural so delighted! I pulled up my horse, and sat and looked; (and social) environment. Their combined experiences span and it was like looking from the top of a castle down into more than two centuries of East Hampshire life. the sea...” William Cobbett was born in Farnham, west Surrey. He had Stoner Hill is sometimes referred to locally as “Little a varied and colourful career in the Army, in publishing, Switzerland” and was part of the Area of Outstanding politics and farming. He once farmed near Botley, Natural Beauty. Hampshire, and was a Member of Parliament in his later years. This walk includes places he visited inRural Rides. Shoulder of Mutton Hill inspired the poet Edward Thomas – a memorial stone is dedicated to him on the hill. The journey down the Hampshire hangers was made by Cobbett on Sunday 24 November 1822, and published in The foot of the chalk escarpment is usually muddy and his newspaper The Political Register later (1830) included slippery: in his book . Cobbett set our from East Meon Rural Rides “After crossing a little field and going through a farm-yard, on horseback to go to Thursley in Surrey but because of his we came into a lane, which was, at once, road and river.” obsessive dislike of heathland, and especially Hindhead, he decided to take a more adventurous route via Hawkley and b Approaching the steep Upper Greensand escarpment Headley: above Scotland Farm, Cobbett descended down the hanger to the Gault clay vale on his way to Greatham: “...at “The map of Hampshire (and we had none of Surrey) showed last, got us safe into the indescribable dirt and mire of the me the way to Headley, which lies on the West of Hindhead, road from Hawkley Green to Greatham. -

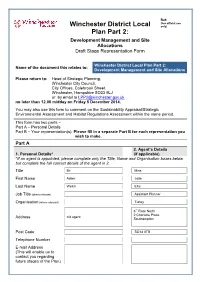

Winchester District Local Plan Part 2: Name of the Document This Relates To: Development Management and Site Allocations

Ref: (For official use Winchester District Local only) Plan Part 2: Development Management and Site Allocations Draft Stage Representation Form Winchester District Local Plan Part 2: Name of the document this relates to: Development Management and Site Allocations Please return to: Head of Strategic Planning, Winchester City Council, City Offices, Colebrook Street, Winchester, Hampshire SO23 9LJ or by email to [email protected] no later than 12.00 midday on Friday 5 December 2014. You may also use this form to comment on the Sustainability Appraisal/Strategic Environmental Assessment and Habitat Regulations Assessment within the same period. This form has two parts – Part A – Personal Details Part B – Your representation(s). Please fill in a separate Part B for each representation you wish to make. Part A 2. Agent’s Details 1. Personal Details* (if applicable) *If an agent is appointed, please complete only the Title, Name and Organisation boxes below but complete the full contact details of the agent in 2. Title Mr Miss First Name Adam Jade Last Name Welch Ellis Job Title (where relevant) Assistant Planner Organisation (where relevant) Turley th 6 Floor North 2 Charlotte Place c/o agent Address Southampton Post Code SO14 0TB Telephone Number E-mail Address (This will enable us to contact you regarding future stages of the Plan) Part B – Comments on Local Plan Part 2 and supporting documents. Use this section to set out your comments on Local Plan Part 2 or supporting documents (such as the Sustainability Appraisal or Habitat Regulations Assessment). Please use a separate sheet for each representation. -

1St – 31St May 2021 Welcome

ALTON Walking & Cycling Festival 1st – 31st May 2021 Welcome... Key: to Alton Town Councils walking and cycling festival. We are delighted that Walking experience isn’t necessary for this year’s festival is able to go ahead and that we are able to offer a range Easy: these as distances are relatively short and paths and of walks and cycle rides that will suit not only the more experienced enthusiast gradients generally easy. These walks will be taken but also provide a welcome introduction to either walking or cycling, or both! at a relaxed pace, often stopping briefly at places of Alton Town Council would like wish to thank this year’s main sponsor, interest and may be suitable for family groups. the Newbury Buiding Society and all of the volunteers who have put together a programme to promote, share and develop walking and cycling in Moderate: These walks follow well defined paths and tracks, though they may be steep in places. They and around Alton. should be suitable for most people of average fitness. Please Note: Harder: These walks are more demanding and We would remind all participants that they must undertake a self-assessment there will be some steep climbs and/or sustained for Covid 19 symptoms and no-one should be participating in a walk or cylcle ascent and descent and rough terrain. These walks ride if they, or someone they live with, or have recently been in close contact are more suitable for those with a good level of with have displayed any symptoms. fitness and stamina. -

Winchester Cathedral Close

PAPERS AND PROCEEDINGS ' 9 WINCHESTER CATHEDRAL CLOSE. By T. D. ATKINSON. Present Lay-out. HE Cathedral precincts of to-day are conterminous with those of the Middle Ages-containing the Priory of Saint Swithun, T and are still surrounded by the great wall of the monastery. ' But while the church itself has been lucky in escaping most of the misfortunes which have overtaken so many cathedral and other churches, the monastic, buildings have been among the most unfortunate. The greater number have been entirely destroyed. The present lay-out of the Close not only tells us nothing of the monastic plan, but so far as possible misleads us. The only building which informs us of anything that we could not have guessed for ourselves is the Deanery. That does tell us at least where the Prior v lived. For the rest, the site of the very dorter, as the monks called their dormitory, is uncertain, while we are still more ignorant of the position of the infirmary, a great building probably measuring 200. feet by 50 feet.1 There is little left either of material remains, or of documentary evidence to give us a hint on these things, for the documents have perished and the general topography has been turned upside down and its character entirely transformed. Upside down because the main entrance to the precincts is now on the South, whereas it was formerly to the North, and transformed because the straight walks . of the cloister and the square courts and gardens harmonizing with the architecture have given place to elegant serpentine carriage sweeps which branch into one another with easy curves, like a well-planned railway junction. -

Community Planning in Winchester

Legend Parish Outlines Work in Progress ± Plans Completed Micheldever Wonston Northington South Wonston Old Alresford Bighton Crawley Kings Worthy Itchen Stoke and Littleton Ovington and Headbourne New Itchen Valley Harestock Worthy Alresford Sparsholt Bishops Sutton Winchester City see inset Tichborne Chilcomb Badger Farm Cheriton Bramdean and Hinton Ampner Olivers Battery Hursley Kilmeston Compton and Shawford Twyford Beauworth West Meon Owslebury Warnford Otterbourne Colden Common Exton Upham Corhampton and Meonstoke Bishops Waltham Droxford Durley Hambledon Swanmore Winchester City Area Soberton Shedfield Harestock Curdridge St Barnabas Ward Abbots Barton Denmead St Bartholomew Ward Wickham Winnall St Paul Ward Boarhunt Whiteley Newlands Southwick and Widley Highcliffe St Luke Stanmore Ward St Michaels Ward Soberton Updated 05/12/2011 Upham Updated 23/12/2014 Swanmore and Shedfield updated 16/08/2011 Denmead Updated 24/04/2015 Itchen Valley updated 22/02/2012 Abbots Barton Added 24/04/2015 Kings Worthy Updated 16/04/2012 Droxford Updated 15/09/2015 Winnall Updated 04/05/2012 Durley Updated 15/09/2015 Chilcomb Updated 22/05/2012 Wonston updated 15/09/2015 Northington and Upham updated 09/10/2012 Sparsholt added 25/01/2016 COMMUNITY PLANNING IN WINCHESTER Hambledon Updated 22/01/2013 Twyford added 01/07/2016 Durley and Wonston Updated 18/03/2013 Shedfield completed 04/04/2016 Durley and Wonston Updated 18/03/2013 Highcliffe completed 10/06/2016 St Barnabas and HarestockUpdated 06/04/2013 Kilmeston added 10/06/2016 © Crown copyright and database rights Owslebury updated 06/04/2013 Hursley added 06/06/2017 Northington updated 31/07/2013 Bishops Sutton updated 27/09/2019 Winchester City Council license 100019531 Highcliffe added 19/08/2013 Ollivers Battery completed 27/09/2019 2020. -

Winchester District Local Plan Part 1 – Joint Core Strategy

Part of the Winchester district development framework Winchester District Local Plan Part 1 – Joint Core Strategy Pre-submission December 2011 1.0 Introduction and Background ..................................................................1 The Winchester District Local Plan Part 1 – Joint Core Strategy Preparation and Consultation ............................................................................................3 Winchester District Community Strategy ........................................................4 Sustainability Appraisal, Strategic Environmental Assessment, Habitats Regulations Assessment and Equalities Impact Assessment ........................6 Other Plans and Strategies ............................................................................7 Statutory Compliance Requirements..............................................................9 Policy Framework.........................................................................................10 2.0 Profile of Winchester District .................................................................11 Winchester Town..........................................................................................14 South Hampshire Urban Areas.....................................................................15 Market Towns and Rural Area......................................................................16 Spatial Planning Vision.................................................................................18 Spatial Planning Objectives..........................................................................18