Appendix 9A Pages 101-191

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NH Trout Stocking - April 2018

NH Trout Stocking - April 2018 Town WaterBody 3/26‐3/30 4/02‐4/06 4/9‐4/13 4/16‐4/20 4/23‐4/27 4/30‐5/04 ACWORTH COLD RIVER 111 ALBANY IONA LAKE 1 ALLENSTOWN ARCHERY POND 1 ALLENSTOWN BEAR BROOK 1 ALLENSTOWN CATAMOUNT POND 1 ALSTEAD COLD RIVER 1 ALSTEAD NEWELL POND 1 ALSTEAD WARREN LAKE 1 ALTON BEAVER BROOK 1 ALTON COFFIN BROOK 1 ALTON HURD BROOK 1 ALTON WATSON BROOK 1 ALTON WEST ALTON BROOK 1 AMHERST SOUHEGAN RIVER 11 ANDOVER BLACKWATER RIVER 11 ANDOVER HIGHLAND LAKE 11 ANDOVER HOPKINS POND 11 ANTRIM WILLARD POND 1 AUBURN MASSABESIC LAKE 1 1 1 1 BARNSTEAD SUNCOOK LAKE 1 BARRINGTON ISINGLASS RIVER 1 BARRINGTON STONEHOUSE POND 1 BARTLETT THORNE POND 1 BELMONT POUT POND 1 BELMONT TIOGA RIVER 1 BELMONT WHITCHER BROOK 1 BENNINGTON WHITTEMORE LAKE 11 BENTON OLIVERIAN POND 1 BERLIN ANDROSCOGGIN RIVER 11 BRENTWOOD EXETER RIVER 1 1 BRISTOL DANFORTH BROOK 11 BRISTOL NEWFOUND LAKE 1 BRISTOL NEWFOUND RIVER 11 BRISTOL PEMIGEWASSET RIVER 11 BRISTOL SMITH RIVER 11 BROOKFIELD CHURCHILL BROOK 1 BROOKFIELD PIKE BROOK 1 BROOKLINE NISSITISSIT RIVER 11 CAMBRIDGE ANDROSCOGGIN RIVER 1 CAMPTON BOG POND 1 CAMPTON PERCH POND 11 CANAAN CANAAN STREET LAKE 11 CANAAN INDIAN RIVER 11 NH Trout Stocking - April 2018 Town WaterBody 3/26‐3/30 4/02‐4/06 4/9‐4/13 4/16‐4/20 4/23‐4/27 4/30‐5/04 CANAAN MASCOMA RIVER, UPPER 11 CANDIA TOWER HILL POND 1 CANTERBURY SPEEDWAY POND 1 CARROLL AMMONOOSUC RIVER 1 CARROLL SACO LAKE 1 CENTER HARBOR WINONA LAKE 1 CHATHAM BASIN POND 1 CHATHAM LOWER KIMBALL POND 1 CHESTER EXETER RIVER 1 CHESTERFIELD SPOFFORD LAKE 1 CHICHESTER SANBORN BROOK -

Hike Leader Handbook

Excursions Committee New Hampshire Chapter Of the Appalachian Mountain Club Hike Leader Handbook February, 2016 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 2 of 75. 2AMC–NH Chapter Excursions Committee Hike Leader Handbook Table of Contents Letter to New Graduates The Trail to Leadership – Part D Part 1 - Leader Requirements Part 2 – Hike Leader Bill of Rights Part 2a-Leader-Participant Communication Part 3 - Guidelines for Hike Leaders Part 4 - Hike Submission Procedures Part 5 – On-line Hike Entry Instructions (AMC Database) Part 5a – Meetup Posting Instructions Part 6 – Accident & Summary of Use Report Overview Part 7 - AMC Incident Report Form Part 8 - WMNF Use Report Form Part 9 - Excursions Committee Meetings Part 10 - Mentor Program Overview Part 11 – Leader Candidate Requirements Part 12 - Mentor Requirements Part 13 - Mentor Evaluation Form Part 14 - Class 1 & 2 Peaks List Part 15 - Class 3 Peaks List Part 16 - Liability Release Form Instructions Part 17 - Release Form FAQs Part 18 - Release Form Part 19 - Activity Finance Policy Part 20 - Yahoo Group Part 21 – Leadership Recognition Part 22 – Crosswalk between Classes and Committees NH AMC Excursion Committee Bylaws Page 1 of 2 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 3 of 75. Page 2 of 2 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 4 of 75. Hello, Leadership Class Graduate! We hope that you enjoyed yourself at the workshop, and found the weekend worthwhile. We also hope that you will consider becoming a NH Chapter AMC Hike leader—you’ll be a welcome addition to our roster of leaders, and will have a fun and rewarding experience to boot! About the Excursions Committee: We are the hikers in the New Hampshire Chapter, and we also lead some cycling hikes. -

Official List of Public Waters

Official List of Public Waters New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Water Division Dam Bureau 29 Hazen Drive PO Box 95 Concord, NH 03302-0095 (603) 271-3406 https://www.des.nh.gov NH Official List of Public Waters Revision Date October 9, 2020 Robert R. Scott, Commissioner Thomas E. O’Donovan, Division Director OFFICIAL LIST OF PUBLIC WATERS Published Pursuant to RSA 271:20 II (effective June 26, 1990) IMPORTANT NOTE: Do not use this list for determining water bodies that are subject to the Comprehensive Shoreland Protection Act (CSPA). The CSPA list is available on the NHDES website. Public waters in New Hampshire are prescribed by common law as great ponds (natural waterbodies of 10 acres or more in size), public rivers and streams, and tidal waters. These common law public waters are held by the State in trust for the people of New Hampshire. The State holds the land underlying great ponds and tidal waters (including tidal rivers) in trust for the people of New Hampshire. Generally, but with some exceptions, private property owners hold title to the land underlying freshwater rivers and streams, and the State has an easement over this land for public purposes. Several New Hampshire statutes further define public waters as including artificial impoundments 10 acres or more in size, solely for the purpose of applying specific statutes. Most artificial impoundments were created by the construction of a dam, but some were created by actions such as dredging or as a result of urbanization (usually due to the effect of road crossings obstructing flow and increased runoff from the surrounding area). -

Partnership Opportunities for Lake-Friendly Living Service Providers NH LAKES Lakesmart Program

Partnership Opportunities for Lake-Friendly Living Service Providers NH LAKES LakeSmart Program Only with YOUR help will New Hampshire’s lakes remain clean and healthy, now and in the future. The health of our lakes, and our enjoyment of these irreplaceable natural resources, is at risk. Polluted runoff water from the landscape is washing into our lakes, causing toxic algal blooms that make swimming in lakes unsafe. Failing septic systems and animal waste washed off the land are contributing bacteria to our lakes that can make people and pets who swim in the water sick. Toxic products used in the home, on lawns, and on roadways and driveways are also reaching our lakes, poisoning the water in some areas to the point where fish and other aquatic life cannot survive. NH LAKES has found that most property owners don’t know how their actions affect the health of lakes. We’ve also found that property owners want to do the right thing to help keep the lakes they enjoy clean and healthy and that they often need help of professional service providers like YOU! What is LakeSmart? The LakeSmart program is an education, evaluation, and recognition program that inspires property owners to live in a lake- friendly way, keeping our lakes clean and healthy. The program is free, voluntary, and non-regulatory. Through a confidential evaluation process, property owners receive tailored recommendations about how to implement lake-friendly living practices year-round in their home, on their property, and along and on the lake. Property owners have access to a directory of lake- friendly living service providers to help them adopt lake-friendly living practices. -

Board of Selectmen Minutes

TOWN OF DEERING Board of Selectmen 762 Deering Center Road Deering, NH 03244 Meeting Minutes June 20, 2018 Selectmen present: Aaron Gill, Allen Belouin, John Shaw. The meeting was called to order at 1900. MEETING MINUTES: Meeting Minutes – June 20th. Mr. Gill made the motion to approve the June 20th meeting minutes. Mr. Belouin seconded the motion. The vote was unanimous and so moved. New Business Gary Samuels – Little Library Placement Library Trustees Gary Samuels and Betsy Holmes spoke about the concept of a “Little Free Library” explaining that they are a small, boxlike structure mounted to a post where books can be taken and returned. Given the absence of a full-time library the Trustees believed that the “Little Free Library” represented a good alternative that provided better accessibility to books and reading opportunities for the Deering community. The Board along with the two Library Trustees went outside to look at a recently constructed Little Free Library. Discussion about its location on the Town Office grounds ensued with a decision about its final placement left until consultation with the Road Agent. Handicap accessibility and snow removal being prime concerns related to its placement. Little Free Library Example Fire Department – Per Diem New Hires Fire Chief Dan Gorman introduced two new hires, Troy Normandin who is an advanced EMT and Fire Fighter, and Drew Bertolino who is a paramedic. Board members welcomed the new hires and all agreed that they will make valuable contributions to the department. Intent to Cut – Mike Mullen Mr. Gill explained to those present that Mr. -

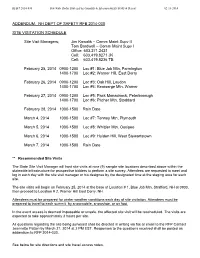

State of New Hampshire

RFB # 2014-030 Statewide Radio System Functionality & Interoperability Study & Report 02-10-2014 ADDENDUM. NH DEPT OF SAFETY RFB 2014-030 SITE VISITATION SCHEDULE Site Visit Managers; Jim Kowalik – Comm Maint Supv II Tom Bardwell – Comm Maint Supv I Office: 603.271.2421 Cell: 603.419.8271 JK Cell: 603.419.8236 TB February 25, 2014 0900-1200 Loc #1: Blue Job Mtn, Farmington 1400-1700 Loc #2: Warner Hill, East Derry February 26, 2014 0900-1200 Loc #3: Oak Hill, Loudon 1400-1700 Loc #4: Kearsarge Mtn, Warner February 27, 2014 0900-1200 Loc #5: Pack Monadnock, Peterborough 1400-1700 Loc #6: Pitcher Mtn, Stoddard February 28, 2014 1000-1500 Rain Date March 4, 2014 1000-1500 Loc #7: Tenney Mtn, Plymouth March 5, 2014 1000-1500 Loc #8: Whittier Mtn, Ossipee March 6, 2014 1000-1500 Loc #9: Holden Hill, West Stewartstown March 7, 2014 1000-1500 Rain Date ** Recommended Site Visits The State Site Visit Manager will host site visits at nine (9) sample site locations described above within the statewide infrastructure for prospective bidders to perform a site survey. Attendees are requested to meet and log in each day with the site visit manager or his designee by the designated time at the staging area for each site. The site visits will begin on February 25, 2014 at the base of Location # 1, Blue Job Mtn, Strafford, NH at 0900, then proceed to Location # 2, Warner Hill East Derry, NH. Attendees must be prepared for winter weather conditions each day of site visitation. Attendees must be prepared to travel to each summit by snowmobile, snowshoe, or on foot. -

Hellcat Boardwalk Trail Replacement Gets the Greenlight! by Matt Poole, Visitor Services Manager

United States Fish & Wildlife Service Summer/Fall, 2019 Hellcat Boardwalk Trail Replacement Gets the Greenlight! by Matt Poole, Visitor Services Manager I always describe the Hellcat Trail Boardwalk as the most valuable and most loved “piece of visitor ser- vices infrastructure” at Parker River National Wild- life Refuge. Hellcat is where LOTS of refuge visitors, from across a broad range of user groups, have been going to observe wildlife in natural habitats for al- most 50 years! The venerable foot path is also a place where one can go simply to enjoy and connect with the rhythms of the natural world. The current boardwalk was built by high school-age, Youth Conservation Corps workers over the course of a handful of summers, beginning in the early 1970s. In its nearly half century of public service, Hellcat has never experienced a major facelift or Photo: Matt Poole/FWS overhaul. I always marvel that the original pressure The new Hellcat Boardwalk Trail will be completely wheel- treated lumber out there continues to support ref- chair accessible. uge visitors’ wildlife and nature experiences all these years later. As I always say, that old lumber “doesn’t owe anyone anything!” Just imagine this: In This Issue... It’s literally possible, if not probable, that someone Hellcat Boardwalk Replacement Gets Greenlight .......... 1 who, as a child, scrambled along the Hellcat board- walk back in 1972 has, in 2019, chased their own Restoring the Lower Peverly Pond Dam ......................... 3 grandchild down that very same stretch of board- Making Watershed Connections Personal ..................... 5 walk! But, nothing lasts forever… Exploring Wapack National Wildlife Refuge .................. -

Fall 2009 Vol. 28 No. 3

V28 No3 Fall09_final 5/19/10 8:41 AM Page i New Hampshire Bird Records Fall 2009 Vol. 28, No. 3 V28 No3 Fall09_final 5/19/10 8:41 AM Page ii AUDUBON SOCIETY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE New Hampshire Bird Records Volume 28, Number 3 Fall 2009 Managing Editor: Rebecca Suomala 603-224-9909 X309, [email protected] Text Editor: Dan Hubbard Season Editors: Pamela Hunt, Spring; Tony Vazzano, Summer; Stephen Mirick, Fall; David Deifik, Winter Layout: Kathy McBride Assistants: Jeannine Ayer, Lynn Edwards, Margot Johnson, Susan MacLeod, Marie Nickerson, Carol Plato, William Taffe, Jean Tasker, Tony Vazzano Photo Quiz: David Donsker Photo Editor: Jon Woolf Web Master: Len Medlock Editorial Team: Phil Brown, Hank Chary, David Deifik, David Donsker, Dan Hubbard, Pam Hunt, Iain MacLeod, Len Medlock, Stephen Mirick, Robert Quinn, Rebecca Suomala, William Taffe, Lance Tanino, Tony Vazzano, Jon Woolf Cover Photo: Western Kingbird by Leonard Medlock, 11/17/09, at the Rochester wastewater treatment plant, NH. New Hampshire Bird Records is published quarterly by New Hampshire Audubon’s Conservation Department. Bird sight- ings are submitted to NH eBird (www.ebird.org/nh) by many different observers. Records are selected for publication and not all species reported will appear in the issue. The published sightings typically represent the highlights of the season. All records are subject to review by the NH Rare Birds Committee and publication of reports here does not imply future acceptance by the Committee. Please contact the Managing Editor if you would like to report your sightings but are unable to use NH eBird. New Hampshire Bird Records © NHA April, 2010 www.nhbirdrecords.org Published by New Hampshire Audubon’s Conservation Department Printed on Recycled Paper V28 No3 Fall09_final 5/19/10 8:41 AM Page 1 IN MEMORY OF Tudor Richards We continue to honor Tudor Richards with this third of the four 2009 New Hampshire Bird Records issues in his memory. -

Fall 1997 Vol. 16 No. 3

NevnHomprhire Bird Records Foll | 997 Vol. | 6, No. 3 Fromrhe Ediror We are pleased to honor Kimball Elkins in this issue of New Hampshire Bird Records. Kimball was the Fall Editor for many years and later served as Technical Editor until his death in Septemberof L997. All of us will miss Kimball, who was not only a valuable resourceon birds in the statebut also a wonderful person. A special thank you to SusanFogleman for the cover illustration of a Barred Owl which originally appearedinlhe Atlas of Breeding Birds in New Hampshire. Susan's artworkmaybefoundthroughoutthisissueofNewHampshireBirdRecordsinmemory of Kimball Elkin's friendship and mentoring. We appreciate the support of the donors who sponsoredthis issue in Kimball's memory. Donations may also be made in Kimball's honor to a fund for the revision of his Checklist of the Birds of New Hampshire. Pleasecontact me at 224-9909 for more information. BeclcySuomala Managing Editor New HampshirizBird Records (NHBR) is published quarterly by the Audubon Society of New Hampshire (ASNH). Bird sightings are submitted to ASNH and are edited for publication. A computerized printout of all sightings in a seasonis available for a fee. To order a printout, purchaseback issues,or volunteer your observationsfor NfIBR, please contact the Managing Editor at224-9909. We are always interested in receiving sponsorshipfor NH Bird Records. If you or a company/organization you work for would be interested, pleasecontact Becky Suomalaat224-9909. Published by rhe Audubon Society of New Hompshire New Hampshire Bird Records @ ASNH 1998 \!rd^@^ Printedon RecycledPaper Dedicofion Kimball Elkins, a long-time editor of New Hampshire Bird Records, loved birds and birding. -

Biennial Report Forestry Division

iii Nvw 3Jtampstin BIENNIAL REPORT of the FORESTRY DIVISION Concord, New Hampshire 1953 - 1954 TABLE OF CONTENTS REPORT TO GOVERNOR AND COUNCIL 3 REPORT OF THE FORESTRY DIVISION Forest Protection Forest Fire Service 5 Administration 5 Central Supply and Warehouse Building 7 Review of Forest Fire Conditions 8 The 1952 Season (July - December) 8 The 1953 Season 11 The 1954 Season (January - June) 19 Fire Prevention 21 Northeastern Forest Fire Protection Commission 24 Training of Personnel 24 Lookout Station Improvement and lVlaintenance 26 State Fire Fighting Equipment 29 Town Fire Fighting Equipment 30 Radio Communication 30 Fire Weather Stations and Forecasts 32 Wood-Processing Mill Registrations 33 White Pine Blister Rust Control 34 Forest Insects and Diseases 41 Hurricane Damage—1954 42 Public Forests State Forests and Reservations 43 Management of State Forests 48 State Forest Nursery and Reforestation 53 Town Forests 60 White Mountain National Forest 60 Private Forestry County Forestry Program 61 District Forest Advisory Boards 64 Registered Arborists 65 Forest Conservation and Taxation Act 68 Surveys and Statistics Forest Research 68 Forest Products Cut in 1952 and 1953 72 Forestry Division Appropriations 1953 and 1954 78 REPORT OF THE RECREATION DIVISION 81 Revision of Forestry and Recreation Laws j REPORT To His Excellency the Governor and the Honorable Council: The Forestry and Recreation Commission submits herewith its report for the two fiscal years ending June 30, 1954. This consists of a record of the activities of the two Divisions and brief accounts of related agencies prepared by the State Forester and Director of Recrea tion and their staffs. -

Mount Watatic Reservation RMP

Mount Watatic Reservation RMP Mount Watatic Reservation – Resource Management Plan References Ashburnham, Massachusetts. Open Space and Recreation Plan, 2004-2009. Ashby, Massachusetts. Open Space and Recreation Plan, 1999-2004. Clark, Frances (Carex Associates), 1999. Biological Survey of Mt. Watatic Wildlife Management Area and Vicinity. Prepared for Mass. Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Division of Conservation Services. 2000. Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan. Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program. 2001. Biomap: Guiding Land Conservation for Biodiversity in Massachusetts. Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program. 2003. Living Waters: Guiding the Protection of Freshwater Biodiversity in Massachusetts. Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program. 2004. Species Data and Community Stewardship Information. Grifith, G.E., J.M. Omernik, S.M. Pierson, and C.W. Kiilsgaard. 1994. The Massachusetts Ecological Regions Project. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Publication No.17587-74-6/94-DEP. Johnson, Stephen F. 1995. Ninnuock (The People), The Algonquin People of New England. Bliss Publishing, Marlborough, Mass. Massachusetts Invasive Plant Advisory Group. 2005. Strategic Recommendations for Managing Invasive Plants in Massachusetts. -

Ski NH 4-Season Press Kit? This Press Kit Highlights Story Ideas, Photos, Videos and Contact Information for Media Relations People at Each Ski Area

4-SEASON PRESS KIT We're not just winter. The New Hampshire experience spans across all four seasons. 4-SEASON PRESS KIT Story Ideas for Every Season Ski NH's new 4-Season Press Kit was created to help provide media professionals with story ideas about New Hampshire's ski areas for all seasons. This is a living document, for the most up-to-date press kit information as well as links to photos visit the links on this page: https://www.skinh.com/about-us/media. For press releases visit: https://www.skinh.com/about-us/media/press-releases. What is the Ski NH 4-Season Press Kit? This press kit highlights story ideas, photos, videos and contact information for media relations people at each ski area. This new-style press kit offers much more for media than contact lists and already- published resort photos, it offers unique ski area story ideas in one convenient location--covering all seasons. As this is a working document, more ski areas are being added weekly. Visit the links above for the most up-to-date version. Enjoy, Shannon Dunfey-Ball Marketing & Communications Manager Shannon @SkiNH.com Are you interested in exploring New Hampshire's ski area offerings? Email Shannon with your media inquiries and she will help you make the connections you need. WWW.SKINH.COM Winter 2019-20 Media Kit Welcome to Loon Mountain Resort, New England’s most- Loon also offers plenty of exciting four-season activities, accessible mountain destination. Located in New Hampshire’s including scenic gondola rides, downhill mountain biking, White Mountains two hours north of Boston, Loon has been in summit glacial caves, ziplines and climbing walls, to name a few.