Koch Coinage: a Study in Historical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pro- Poor Tourism As an Approach Towards Community Development: a Case Study

South Asian Journal of Tourism and Heritage (2010), Vol. 3, No. 2 Pro- Poor Tourism as an Approach towards Community Development: A Case Study PIYAL BASU ROY*, TAMAL BASU ROY** and SUKANTA SAHA*** *Piyal Basu Roy, Head, Department of Geography, Alipurduar College, West Bengal, India. **Tamal Basu Roy, Dept. of Geography, North Bengal University, West Bengal, India ***Sukanta Das, Dept. of Geography, Visva Bharati University, Santiniketan, India ABSTRACT Pro-Poor Tourism is an innovative idea in tourism sector that has been introduced to strengthen economic well being of communities. It emphasizes work participation of poorer people of the society, makes them engaged in employment and self-help sector and establishes a synthesis between development of tourism by upgrading the degree of livelihood status of poor people so that poverty eradication is possible and socio economic status of poor people is improved. Thus, it encourages poor people to participate more effectively in their developmental processes. Active participation in this field includes sincere participation in work for all poor people ranging from different local communities and belonging to below poverty line of an area. Strategies have been developed to implement this sort of tourism in backward but tourism potential areas in several developing countries in order to generate local employment, resource utilization and management in particular. Investment from different level is encouraged to micro level development to pull tourists to enhance economic prosperity and social interaction with communities in this innovative approach. Here, the ultimate objective is to achieve the net benefits that go in favor of poor people. The paper highlights about the tourism potential of Cooch Behar district of West Bengal as an area of study and seeks to introduce and develop Pro-poor tourism to improve the living standard of poor communities as well as rejuvenate local economy. -

Paper Code: Dttm C205 Tourism in West Bengal Semester

HAND OUT FOR UGC NSQF SPONSORED ONE YEAR DILPOMA IN TRAVEL & TORUISM MANAGEMENT PAPER CODE: DTTM C205 TOURISM IN WEST BENGAL SEMESTER: SECOND PREPARED BY MD ABU BARKAT ALI UNIT-I: 1.TOURISM IN WEST BENGAL: AN OVERVIEW Evolution of Tourism Department The Department of Tourism was set up in 1959. The attention to the development of tourist facilities was given from the 3 Plan Period onwards, Early in 1950 the executive part of tourism organization came into being with the appointment of a Tourist Development Officer. He was assisted by some of the existing staff of Home (Transport) Department. In 1960-61 the Assistant Secretary of the Home (Transport) Department was made Director of Tourism ex-officio and a few posts of assistants were created. Subsequently, the Secretary of Home (Transport) Department became the ex-officio Director of Tourism. Two Regional Tourist Offices - one for the five North Bengal districts i.e., Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri, Cooch Behar, West Dinajpur and Maida with headquarters at Darjeeling and the other for the remaining districts of the State with headquarters at Kolkata were also set up. The Regional Office at KolKata started functioning on 2nd September, 1961. The Regional Office in Darjeeling was started on 1st May, 1962 by taking over the existing Tourist Bureau of the Govt. of India at Darjeeling. The tourism wing of the Home (Transport) Department was transferred to the Development Department on 1st September, 1962. Development. Commissioner then became the ex-officio Director of Tourism. Subsequently, in view of the increasing activities of tourism organization it was transformed into a full-fledged Tourism Department, though the Secretary of the Forest Department functioned as the Secretary, Tourism Department. -

Bir Chilarai

Bir Chilarai March 1, 2021 In news : Recently, the Prime Minister of India paid tribute to Bir Chilarai(Assam ‘Kite Prince’) on his 512th birth anniversary Bir Chilarai(Shukladhwaja) He was Nara Narayan’s commander-in-chief and got his name Chilarai because, as a general, he executed troop movements that were as fast as a chila (kite/Eagle) The great General of Assam, Chilarai contributed a lot in building the Koch Kingdom strong He was also the younger brother of Nara Narayan, the king of the Kamata Kingdom in the 16th century. He along with his elder brother Malla Dev who later known as Naya Narayan attained knowledge about warfare and they were skilled in this art very well during their childhood. With his bravery and heroism, he played a crucial role in expanding the great empire of his elder brother, Maharaja Nara Narayan. He was the third son of Maharaja Biswa Singha (1523–1554 A.D.) The reign of Maharaja Viswa Singha marked a glorious episode in the history of Assam as he was the founder ruler of the Koch royal dynasty, who established his kingdom in 1515 AD. He had many sons but only four of them were remarkable. With his Royal Patronage Sankardeva was able to establish the Ek Saran Naam Dharma in Assam and bring about his cultural renaissance. Chilaray is said to have never committed brutalities on unarmed common people, and even those kings who surrendered were treated with respect. He also adopted guerrilla warfare successfully, even before Shivaji, the Maharaja of Maratha Empire did. -

Class-8 New 2020.CDR

Class - VIII AGRICULTURE OF ASSAM Agriculture forms the backbone of the economy of Assam. About 65 % of the total working force is engaged in agriculture and allied activities. It is observed that about half of the total income of the state of Assam comes from the agricultural sector. Fig 2.1: Pictures showing agricultural practices in Assam MAIN FEATURES OF AGRICULTURE Assam has a mere 2.4 % of the land area of India, yet supports more than 2.6 % of the population of India. The physical features including soil, rainfall and temperature in Assam in general are suitable for cultivation of paddy crops which occupies 65 % of the total cropped area. The other crops are wheat, pulses and oil seeds. Major cash crops are tea, jute, sugarcane, mesta and horticulture crops. Some of the crops like rice, wheat, oil seeds, tea , fruits etc provide raw material for some local industries such as rice milling, flour milling, oil pressing, tea manufacturing, jute industry and fruit preservation and canning industries.. Thus agriculture provides livelihood to a large population of Assam. AGRICULTURE AND LAND USE For the purpose of land utilization, the areas of Assam are divided under ten headings namely forest, land put to non-agricultural uses, barren and uncultivable land, permanent pastures and other grazing land, cultivable waste land, current fallow, other than current fallow net sown area and area sown more than once. 72 Fig 2.2: Major crops and their distribution The state is delineated into six broad agro-climatic regions namely upper north bank Brahmaputra valley, upper south bank Brahmaputra valley, Central Assam valley, Lower Assam valley, Barak plain and the hilly region. -

Expounding Design Act, 2000 in Context of Assam's Textile

EXPOUNDING DESIGN ACT, 2000 IN CONTEXT OF ASSAM’S TEXTILE SECTOR Dissertation submitted to National Law University, Assam in partial fulfillment for award of the degree of MASTER OF LAWS Supervised by, Submitted by, Dr. Topi Basar Anee Das Associate Professor of Law UID- SF0217002 National Law university, Assam 2nd semester Academic year- 2017-18 National Law University, Assam June, 2018 SUPERVISOR CERTIFICATE It is to certify that Miss Anee Das is pursuing Master of Laws (LL.M.) from National Law University, Assam and has completed her dissertation titled “EXPOUNDING DESIGN ACT, 2000 IN CONTEXT OF ASSAM’S TEXTILE SECTOR” under my supervision. The research work is found to be original and suitable for submission. Dr. Topi Basar Date: June 30, 2018 Associate Professor of Law National Law University, Assam DECLARATION I, ANEE DAS, pursuing Master of Laws (LL.M.) from National Law University, Assam, do hereby declare that the present Dissertation titled "EXPOUNDING DESIGN ACT, 2000 IN CONTEXT OF ASSAM’S TEXTILE SECTOR" is an original research work and has not been submitted, either in part or full anywhere else for any purpose, academic or otherwise, to the best of my knowledge. Dated: June 30, 2018 ANEE DAS UID- SF0217002 LLM 2017-18 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT To succeed in my research endeavor, proper guidance has played a vital role. At the completion of the dissertation at the very onset, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my research guide Dr. Topi Basar, Associate professor of Law who strengthen my knowledge in the field of Intellectual Property Rights and guided me throughout the dissertation work. -

A Case Study of the Tea Plantation Industry in Himalayan and Sub - Himalayan Region of Bengal (1879 – 2000)

RISE AND FALL OF THE BENGALI ENTREPRENEURSHIP: A CASE STUDY OF THE TEA PLANTATION INDUSTRY IN HIMALAYAN AND SUB - HIMALAYAN REGION OF BENGAL (1879 – 2000) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY BY SUPAM BISWAS GUIDE Dr. SHYAMAL CH. GUHA ROY CO – GUIDE PROFESSOR ANANDA GOPAL GHOSH DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL 2015 JULY DECLARATION I declare that the thesis entitled RISE AND FALL OF THE BENGALI ENTREPRENEURSHIP: A CASE STUDY OF THE TEA PLANTATION INDUSTRY IN HIMALAYAN AND SUB - HIMALAYAN REGION OF BENGAL (1879 – 2000) has been prepared by me under the guidance of DR. Shyamal Ch. Guha Roy, Retired Associate Professor, Dept. of History, Siliguri College, Dist – Darjeeling and co – guidance of Retired Professor Ananda Gopal Ghosh , Dept. of History, University of North Bengal. No part of this thesis has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. Supam Biswas Department of History North Bengal University, Raja Rammuhanpur, Dist. Darjeeling, West Bengal. Date: 18.06.2015 Abstract Title Rise and Fall of The Bengali Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of The Tea Plantation Industry In Himalayan and Sub Himalayan Region of Bengal (1879 – 2000) The ownership and control of the tea planting and manufacturing companies in the Himalayan and sub – Himalayan region of Bengal were enjoyed by two communities, to wit the Europeans and the Indians especially the Bengalis migrated from various part of undivided Eastern and Southern Bengal. In the true sense the Europeans were the harbinger in this field. Assam by far the foremost region in tea production was closely followed by Bengal whose tea producing areas included the hill areas and the plains of the Terai in Darjeeling district, the Dooars in Jalpaiguri district and Chittagong. -

15 Abhijit Datta* ABSTRACT the Eastern Part of Indian Sub-Continent

- Abhijit Datta* ABSTRACT The eastern part of Indian sub-continent is known as Bengal. It carried different names in different times indicating the whole of Bengal. On the other hand, since ancient times to pre-Mughal period Bengal was divided into different geographical divisions. T P V G R S T V V S H T overlapped with each other in different times. In 1947, P I T V -S Harikela formed a separate entity in eastern side of Bengal, which is situated now in Bangladesh. It played an important role in the social, economic and cultural life of Bengal. Located on the seashore it easily maintained a trade relation with the outside world through the overseas route in the period of feudal system in Bengal. Key words: V -S -Harikela, Ai G J N *Assistant Professor, Islampur College, PO-Islampur, Dt-Uttar Dinajpur, India 15 Jhss, Vol. 10, No. 1 , January to June, 2019 Introduction T ‘ ’ T considered as a ‘ ’ b-continent with distinct geo-features.1 Bengal is the name given to the eastern part of the Indian sub- continent, which I I H I K S S N S 2 The above area was b 27˚9ˡ 20˚50ˡ 86˚35ˡ 92˚30ˡ longitude.3 There were deep forests, highlands and mountains in the east, west and north, and the Bay of Bengal in the South. This way these natural girdles surrounded Bengal. As Niharranjan Roy right “ mountains, at the other the sea, and on both sides the hard hilly country, within, all S ”4 In the early period of Indian history, the region of Bengal covered a large territorial area including the modern state of West Bengal and some parts of the adjoining districts of Assam and Bihar and included the parts of present day of Bangladesh. -

About the Koch Rajbanshi

ABOUT THE KOCH RAJBANSHI Photo: Linkan Roy Various legends trace the origin of the Koch Rajbanshi in Siberia region and its affinity with communities like Lepcha and Dimasa. Considered as indigenous people of South Asia, at present they live in lower of Nepal, Northern of Bengal, North Bihar, Northern Bangladesh, whole of Assam, parts Meghalya and Bhutan. These modern geographical areas were once part of the Kamata kingdom ruled by the Koches for many centuries. The Koches also started calling themselves as Rajbanshi to keep connected with their royal lineage of Koch Dynasty of Kamata. Koch Rajbanshis have gone through many social and cultural changes through the centuries and have become an inclusive social category in which many other groups have joined. The transformation of the “Koch” tribal society into the “Koch Rajbanshi” nation is a unique phenomenon. At present when we refer about the Koch Rajbanshi, we actually refer to an inclusive social group, rather than an exclusive community. Koch Rajbanshis are largely Hindus with lots of their own deities and rituals. A large section of Koch Rajbanshi became follower of Islam and the present Muslims of North Bengal, West Assam and Northern Bangladesh known as “Deshi Mushalman” are of Koch Rajbanshi origin. There are also Christian and Buddhist Koch Rajbanshis. During the expansion of the Koch Kamata Empire, Koch Rajbanshi took the initiate of creating a common culture and a common language in the region which is at present popularly termed as Kamatapuri. Small sections of the Koch Rajbanshi people have successfully preserved the Tibeto-Burman Koch language and culture. -

Unit 6: Religious Traditions of Assam

Assamese Culture: Syncretism and Assimilation Unit 6 UNIT 6: RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS OF ASSAM UNIT STRUCTURE 6.1 Learning Objectives 6.2 Introduction 6.3 Religious Traditions of Assam 6.4 Saivism in Assam Saiva centres in Assam Saiva literature of Assam 6.5 Saktism in Assam Centres of Sakti worship in Assam Sakti literature of Assam 6.6 Buddhism in Assam Buddhist centres in Assam Buddhist literature of Assam 6.7 Vaisnavism in Assam Vaisnava centres in Assam Vaisnava literature of Assam 6.8 Let Us Sum Up 6.9 Answer To Check Your Progress 6.10 Further Reading 6.11 Model Questions 6.1 LEARNING OBJECTIVES After going through this unit, you will be able to- know about the religious traditions in Assam and its historical past, discuss Saivism and its influence in Assam, discuss Saktism as a faith practised in Assam, describe the spread and impact on Buddhism on the general life of the people, Cultural History of Assam 95 Unit 6 Assamese Culture: Syncretism and Assimilation 6.2 INTRODUCTION Religion has a close relation with human life and man’s life-style. From the early period of human history, natural phenomena have always aroused our fear, curiosity, questions and a sense of enquiry among people. In the previous unit we have deliberated on the rich folk culture of Assam and its various aspects that have enriched the region. We have discussed the oral traditions, oral literature and the customs that have contributed to the Assamese culture and society. In this unit, we shall now discuss the religious traditions of Assam. -

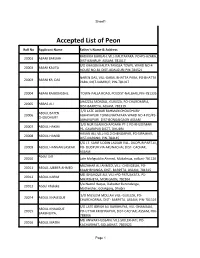

Accepted List of Peon

Sheet1 Accepted List of Peon Roll No Applicant Name Father's Name & Address RADHIKA BARUAH, VILL-KALITAPARA. PO+PS-AZARA, 20001 ABANI BARUAH DIST-KAMRUP, ASSAM, 781017 S/O KHAGEN KALITA TANGLA TOWN, WARD NO-4 20002 ABANI KALITA HOUSE NO-81 DIST-UDALGURI PIN-784521 NAREN DAS, VILL-GARAL BHATTA PARA, PO-BHATTA 20003 ABANI KR. DAS PARA, DIST-KAMRUP, PIN-781017 20004 ABANI RAJBONGSHI, TOWN-PALLA ROAD, PO/DIST-NALBARI, PIN-781335 AHAZZAL MONDAL, GUILEZA, PO-CHARCHARIA, 20005 ABBAS ALI DIST-BARPETA, ASSAM, 781319 S/O LATE AJIBAR RAHMAN CHOUDHURY ABDUL BATEN 20006 ABHAYAPURI TOWN,NAYAPARA WARD NO-4 PO/PS- CHOUDHURY ABHAYAPURI DIST-BONGAIGAON ASSAM S/O NUR ISLAM CHAPGARH PT-1 PO-KHUDIMARI 20007 ABDUL HAKIM PS- GAURIPUR DISTT- DHUBRI HASAN ALI, VILL-NO.2 CHENGAPAR, PO-SIPAJHAR, 20008 ABDUL HAMID DIST-DARANG, PIN-784145 S/O LT. SARIF UDDIN LASKAR VILL- DUDPUR PART-III, 20009 ABDUL HANNAN LASKAR PO- DUDPUR VIA ARUNACHAL DIST- CACHAR, ASSAM Abdul Jalil 20010 Late Mafiguddin Ahmed, Mukalmua, nalbari-781126 MUZAHAR ALI AHMED, VILL- CHENGELIA, PO- 20011 ABDUL JUBBER AHMED KALAHBHANGA, DIST- BARPETA, ASSAM, 781315 MD ISHAHQUE ALI, VILL+PO-PATUAKATA, PS- 20012 ABDUL KARIM MIKIRBHETA, MORIGAON, 782104 S/o Nazrul Haque, Dabotter Barundanga, 20013 Abdul Khaleke Motherjhar, Golakgonj, Dhubri S/O MUSLEM MOLLAH VILL- GUILEZA, PO- 20014 ABDUL KHALEQUE CHARCHORRIA, DIST- BARPETA, ASSAM, PIN-781319 S/O LATE IDRISH ALI BARBHUIYA, VILL-DHAMALIA, ABDUL KHALIQUE 20015 PO-UTTAR KRISHNAPUR, DIST-CACHAR, ASSAM, PIN- BARBHUIYA, 788006 MD ANWAR HUSSAIN, VILL-SIOLEKHATI, PO- 20016 ABDUL MATIN KACHARIHAT, GOLAGHAT, 7865621 Page 1 Sheet1 KASHEM ULLA, VILL-SINDURAI PART II, PO-BELGURI, 20017 ABDUL MONNAF ALI PS-GOLAKGANJ, DIST-DHUBRI, 783334 S/O LATE ABDUL WAHAB VILL-BHATIPARA 20018 ABDUL MOZID PO&PS&DIST-GOALPARA ASSAM PIN-783101 ABDUL ROUF,VILL-GANDHINAGAR, PO+DIST- 20019 ABDUL RAHIZ BARPETA, 781301 Late Fizur Rahman Choudhury, vill- badripur, PO- 20020 Abdul Rashid choudhary Badripur, Pin-788009, Dist- Silchar MD. -

An Introduction to the Sattra Culture of Assam: Belief, Change in Tradition

Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 12 (2): 21–47 DOI: 10.2478/jef-2018-0009 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE SATTRA CULT URE OF ASSAM: BELIEF, CHANGE IN TRADITION AND CURRENT ENTANGLEMENT BABURAM SAIKIA PhD Student Department of Estonian and Comparative Folklore University of Tartu Ülikooli 16, 51003 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT In 16th-century Assam, Srimanta Sankaradeva (1449–1568) introduced a move- ment known as eka sarana nama dharma – a religion devoted to one God (Vishnu or Krishna). The focus of the movement was to introduce a new form of Vaishnava doctrine, dedicated to the reformation of society and to the abolition of practices such as animal sacrifice, goddess worship, and discrimination based on caste or religion. A new institutional order was conceptualised by Sankaradeva at that time for the betterment of human wellbeing, which was given shape by his chief dis- ciple Madhavadeva. This came to be known as Sattra, a monastery-like religious and socio-cultural institution. Several Sattras were established by the disciples of Sankaradeva following his demise. Even though all Sattras derive from the broad tradition of Sankaradeva’s ideology, there is nevertheless some theological seg- mentation among different sects, and the manner of performing rituals differs from Sattra to Sattra. In this paper, my aim is to discuss the origin and subsequent transformations of Sattra as an institution. The article will also reflect upon the implication of traditions and of the process of traditionalisation in the context of Sattra culture. I will examine the power relations in Sattras: the influence of exter- nal forces and the support of locals to the Sattra authorities. -

Muga Silk Rearers: a Field Study of Lakhimpur District of Assam

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 9, ISSUE 04, APRIL 2020 ISSN 2277-8616 Muga Silk Rearers: A Field Study Of Lakhimpur District Of Assam Bharat Bonia Abstract: Assam the centre of North- East India is a highly fascinated state with play to with biodiversity and wealth of natural resource. Lakhimpur is an administrative district in the state of Assam, India. Its headquarter is North Lakhimpur. Lakhimpur district is surrounded by North by Siang and Papumpare district of Arunachal Pradesh and on the East by Dhemaji District and Subansiri River. The geographical location of the district is 26.48’ and 27.53’ Northern latitude and 93.42’ and 94.20' East longitude (approx.). Their existence of rare variety of insects and plants, orchids along various wild animals, birds. And the rest of the jungle and sanctuaries of Assam exerts a great contribution to deliberation of human civilization s. Among all these a peculiar kind of silkworm “Mua” sensitive by nature, rare and valuable living species that makes immense impact on the economy of the state of Assam and Lakhimpur district and paving the way for the muga industry. A Muga silkworm plays an important role in Assamsese society and culture. It also has immense impacts on Assams economy and also have an economic impacts on the people of Lakhimpur district which are specially related with muga rearing activities. Decades are passes away; the demand of Muga is increasing day by day not only in Assam but also in other countries. But the ratio of muga silk production and its demand are disproportionate.