Pre-Meeting Excursion Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards a Housing Strategy to Support Industrial Decentralization: a Case Study of Athi River Town

I TOWARDS A HOUSING STRATEGY TO SUPPORT INDUSTRIAL DECENTRALIZATION: A CASE STUDY OF ATHI RIVER TOWN HENRY MUTHOKA MWAU B.Sc.(Hons) Nairobi, 1986. \ A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PART FULFILMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS (PLANNING) IN THE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI. ;* * * N AND «eg<onal planning OFPA.TTVENT " A - U lT r & ARCHITECTURE, OCSICN -NO OEVFLOPMEn t ' ONIv. RSiTY OK NAlKOil ■“"'Sttrffftas ’ NAIROBI, KENYA (ii) DECLARATION This thesis is my original work and*has not been presented for a degree in any other university• Signed HENRY M. KWAU This thesis has been submitted for examination with my approval as University Supervisor, Signed DR. P.0. ONOIEGE (SUPERVISOR) *av*i*n t o „ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study would not have been successful without the assistance of many people in various institutions. It therefore gives me pleasure to mention a few and express my sincere appreciation for their assistance. First, I would like to thank the Directorate of Personnel Management (DPM)|through the Department of Physical Planning, Ministry of Local Government and Physical Planning whose sponsorship made this work possible. Their collaboration with the department of Urban and Regional Planning, especially through the Chairman, Mr. Z. Maleche, University of Nairobi, made the training course successful. I am greatly indebted to Dr. P. 0. Ondiege, the project supervisor and lecturer in the department, for his guidance throughout the research work. Thanks go to Mr. P. Karanja, the then acting Town Clerk/Treasurer, at time of research work and Mr. Kyatha, both of Athi River Town Council, whose co-operation eased the field work task. -

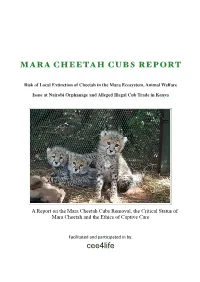

MARA CHEETAH CUBS REPORT Cee4life

MARA CHEETAH CUBS REPORT Risk of Local Extinction of Cheetah in the Mara Ecosystem, Animal Welfare Issue at Nairobi Orphanage and Alleged Illegal Cub Trade in Kenya A Report on the Mara Cheetah Cubs Removal, the Critical Status of Mara Cheetah and the Ethics of Captive Care Facilitated and par-cipated in by: cee4life MARA CHEETAH CUBS REPORT Risk of Local Extinction of Cheetah in the Mara Ecosystem, Animal Welfare Issue at Nairobi Orphanage and Alleged Illegal Cub Trade in Kenya Facilitated and par-cipated in by: cee4life.org Melbourne Victoria, Australia +61409522054 http://www.cee4life.org/ [email protected] 2 Contents Section 1 Introduction!!!!!!!! !!1.1 Location!!!!!!!!5 !!1.2 Methods!!!!!!!!5! Section 2 Cheetahs Status in Kenya!! ! ! ! ! !!2.1 Cheetah Status in Kenya!!!!!!5 !!2.2 Cheetah Status in the Masai Mara!!!!!6 !!2.3 Mara Cheetah Population Decline!!!!!7 Section 3 Mara Cub Rescue!! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!3.1 Abandoned Cub Rescue!!!!!!9 !!3.2 The Mother Cheetah!!!!!!10 !!3.3 Initial Capture & Protocols!!!!!!11 !!3.4 Rehabilitation Program Design!!!!!11 !!3.5 Human Habituation Issue!!!!!!13 Section 4 Mara Cub Removal!!!!!!! !!4.1 The Relocation of the Cubs Animal Orphanage!!!15! !!4.2 The Consequence of the Mara Cub Removal!!!!16 !!4.3 The Truth Behind the Mara Cub Removal!!!!16 !!4.4 Past Captive Cheetah Advocations!!!!!18 Section 5 Cheetah Rehabilitation!!!!!!! !!5.1 Captive Wild Release of Cheetahs!!!!!19 !!5.2 Historical Cases of Cheetah Rehabilitation!!!!19 !!5.3 Cheetah Rehabilitation in Kenya!!!!!20 Section 6 KWS Justifications -

Flash Update

Flash Update Kenya Floods Response Update – 29 June 2018 Humanitarian Situation and Needs Kenya Country Office An estimated 64,045 flood-affected people are still in camps in Galole, Tana Delta and Tana North Sub counties in Tana River County. A comprehensive assessment of the population still displaced in Tana River will be completed next week. Across the country, the heavy long rains season from March to May has displaced a total of 291,171 people. Rainfall continues in the Highlands west of the Rift Valley (Kitale, Kericho, Nandi, Eldoret, Kakamega), the Lake Basin (Kisumu, Kisii, Busia), parts of Central Rift Valley (Nakuru, Nyahururu), the border areas of Northwestern Kenya (Lokichoggio, Lokitaung), and the Coastal strip (Mombasa, Mtwapa, Malindi, Msabaha, Kilifi, Lamu). Humanitarian access by road is constrained due to insecurity along the Turkana-West Pokot border and due to poor roads conditions in Isiolo, Samburu, Makueni, Tana River, Kitui, and Garissa. As of 25 June 2018, a total of 5,470 cases of cholera with 78 deaths have been reported (Case Fatality Rate of 1.4 per cent). Currently, the outbreak is active in eight counties (Garissa, Tana River, Turkana, West Pokot, Meru, Mombasa, Kilifi and Isiolo counties) with 75 cases reported in the week ending 25 June. A total of 111 cases of Rift Valley Fever (RVF) have been reported with 14 death in three counties (Wajir 75, Marsabit 35 and Siaya 1). Case Fatality Rate is reported at 8 per cent in Wajir and 20 per cent in Marsabit. Active case finding, sample testing, ban of slaughter, quarantine, and community sensitization activities are ongoing. -

Using Tows Matrix As a Strategic Decision-Making Tool in Managing KWS Product Portfolio

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319351999 Using Tows Matrix as a Strategic Decision-Making Tool in Managing KWS Product Portfolio Article · August 2017 CITATIONS READS 0 2,950 1 author: Mary Mugo Multimedia University College of Kenya 9 PUBLICATIONS 0 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Mary Mugo on 07 September 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Using Tows Matrix as a Strategic Decision-Making Tool in Managing KWS Product Portfolio 1. Mugo Mary 2. Kamau Florence 3. Mukabi Mary 4. Kemunto Christine 1. Multimedia University of Kenya 2. Multimedia University of Kenya 3. Multimedia University of Kenya 4. Multimedia University of Kenya Abstract In today's changing business environment, product portfolio management is a vital issue. Majority of companies are developing, applying and attaining better results from managing their product portfolio effectively, as the success of any organization is dependent on how well it manages its products and services especially in an unpredictable business environment. The aim of this study was to understand the concept of SWOT analysis as a decision making tool that can be used to manage the product portfolio of Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) with the aim of maximizing returns and staying competitive in a dynamic business environment. The study was conducted in the eight KWS conservation areas. Primary data was collected through semi structured questionnaires and in depth interviews. Collected data was analyzed using descriptive statistics. Research findings revealed that each conservancy had its own strengths, weaknesses, threats, and opportunities; some unique and others similar. -

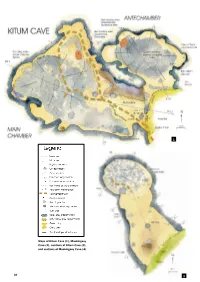

30 SWARA October – December 2007 Maps of Kitum Cave

1 Maps of Kitum Cave (1), Mackingeny Cave (2), sections of Kitum Cave (3), and sections of Mackingeny Cave (4). 30 SWARA October – December 2007 2 behaviour 3 Mount Elgon’s ‘elephant caves’ Joyce Lundberg and Donald McFarlane contemplate and map the extraordinary underground attractions of western Kenya’s Mount Elgon National Park. 4 SWARA October – December 2007 31 ne of Kenya’s least vis- that are far too busy eating the herbivore ited parks, the Mount equivalent of chocolate mousse to take Elgon National Park much notice of their potential fate. Oprotects a narrow band The salts are mainly mirabalite, of forest climbing the eastern flank sodium sulphate (commonly called of East Africa’s fifth highest mas- Glauber’s salt), which grows out sif, standing 4,321 metres (14,178 from the walls and can form curved crys- feet) above sea level (see map below). tals resembling pig’s tusks. The crystals are For most visitors, the Park’s principal licked off the wall by buffalos or scraped/ attraction rests in its suite of unique caves, gouged out by bushbuck and elephants. of which the Kitum and the Makingeny Buffalos cannot scrape the rock themselves, Caves are best known. Used by the Elgony so they eat mainly the leftover bits dropped people for centuries, the Elgon caves came by the elephants. The marks left by bush- to wider attention through the writings of buck teeth and elephant tusks are clearly Joseph Thomson (Through Masai Land, identifiable on the cave walls. 1885), and are thought to have been the These marks should not be confused inspiration too for H. -

KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis

REPUBLIC OF KENYA KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis Published by the Government of Kenya supported by United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce National Council for Population and Development (NCPD) P.O. Box 48994 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-271-1600/01 Fax: +254-20-271-6058 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ncpd-ke.org United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce P.O. Box 30218 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-76244023/01/04 Fax: +254-20-7624422 Website: http://kenya.unfpa.org © NCPD July 2013 The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the contributors. Any part of this document may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced or translated in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. It may not be sold or used inconjunction with commercial purposes or for prot. KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS JULY 2013 KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS i ii KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................iv FOREWORD ..........................................................................................................................................ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ..........................................................................................................................x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................xi -

Staging Nation Statist Self-Identity in Jaramogi Odinga's Not Yet Uhuru (1967).Pdf

WORLD Journal of Postcolonial Writing and World Literatures https://royalliteglobal.com LITERATURES Staging Nation Statist Self-Identity in Jaramogi Odinga’s Not Yet Uhuru (1967) George Obara Nyandoro Department of Languages, Linguistics and Literature, This article is published by Royallite Kisii University, Kenya Global, P. O. Box 26454-Nairobi Email: [email protected] 00504 Kenya in the: Journal of Postcolonial Abstract Writing and World This article argues that an autobiographer, at the time Literatures of writing about self, is aware of existing public perception about who s/he is. The construction of self Volume 1, Issue 1, 2020 in the autobiography is therefore a form of staging self © 2020 The Author(s) as an interplay between knowledge of self against This open access article is nuanced public understanding of the autobiographer distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) and circumstances which produce him. The paper 4.0 license. employs Istvan Dobos’s argument on autobiography as a staging of self to analyse how Oginga Odinga Article Information Submitted: 30th April 2020 constructs self in his Not Yet Uhuru. The paper is also Accepted: 5th May 2020 informed by Craig Calhoun’s theory of nationalism Published: 15th May 2020 Conflict of Interest: No potential particularly his arguments on the construction of civic conflict of interest was reported nationalist identities. The paper relied on close reading by the author of the text to evaluate how the autobiographical self- Funding: None constructs self-relative to his thematic thrust a well as Additional information is relative to other characters in the text. However, available at the end of the article insights of the context which informed the autobiography were gleaned by extrapolating other secondary texts. -

Download List of Physical Locations of Constituency Offices

INDEPENDENT ELECTORAL AND BOUNDARIES COMMISSION PHYSICAL LOCATIONS OF CONSTITUENCY OFFICES IN KENYA County Constituency Constituency Name Office Location Most Conspicuous Landmark Estimated Distance From The Land Code Mark To Constituency Office Mombasa 001 Changamwe Changamwe At The Fire Station Changamwe Fire Station Mombasa 002 Jomvu Mkindani At The Ap Post Mkindani Ap Post Mombasa 003 Kisauni Along Dr. Felix Mandi Avenue,Behind The District H/Q Kisauni, District H/Q Bamburi Mtamboni. Mombasa 004 Nyali Links Road West Bank Villa Mamba Village Mombasa 005 Likoni Likoni School For The Blind Likoni Police Station Mombasa 006 Mvita Baluchi Complex Central Ploice Station Kwale 007 Msambweni Msambweni Youth Office Kwale 008 Lunga Lunga Opposite Lunga Lunga Matatu Stage On The Main Road To Tanzania Lunga Lunga Petrol Station Kwale 009 Matuga Opposite Kwale County Government Office Ministry Of Finance Office Kwale County Kwale 010 Kinango Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Floor,At Junction Off- Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Kinango Ndavaya Road Floor,At Junction Off-Kinango Ndavaya Road Kilifi 011 Kilifi North Next To County Commissioners Office Kilifi Bridge 500m Kilifi 012 Kilifi South Opposite Co-Operative Bank Mtwapa Police Station 1 Km Kilifi 013 Kaloleni Opposite St John Ack Church St. Johns Ack Church 100m Kilifi 014 Rabai Rabai District Hqs Kombeni Girls Sec School 500 M (0.5 Km) Kilifi 015 Ganze Ganze Commissioners Sub County Office Ganze 500m Kilifi 016 Malindi Opposite Malindi Law Court Malindi Law Court 30m Kilifi 017 Magarini Near Mwembe Resort Catholic Institute 300m Tana River 018 Garsen Garsen Behind Methodist Church Methodist Church 100m Tana River 019 Galole Hola Town Tana River 1 Km Tana River 020 Bura Bura Irrigation Scheme Bura Irrigation Scheme Lamu 021 Lamu East Faza Town Registration Of Persons Office 100 Metres Lamu 022 Lamu West Mokowe Cooperative Building Police Post 100 M. -

Ruaha Journal of Arts and Social Sciences (RUJASS), Volume 7, Issue 1, 2021

RUAHA J O U R N A L O F ARTS AND SOCIA L SCIENCE S (RUJASS) Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences - Ruaha Catholic University VOLUME 7, ISSUE 1, 2021 1 Ruaha Journal of Arts and Social Sciences (RUJASS), Volume 7, Issue 1, 2021 CHIEF EDITOR Prof. D. Komba - Ruaha Catholic University ASSOCIATE CHIEF EDITOR Rev. Dr Kristofa, Z. Nyoni - Ruaha Catholic University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Prof. A. Lusekelo - Dar es Salaam University College of Education Prof. E. S. Mligo - Teofilo Kisanji University, Mbeya Prof. G. Acquaviva - Turin University, Italy Prof. J. S. Madumulla - Catholic University College of Mbeya Prof. K. Simala - Masinde Murilo University of Science and Technology, Kenya Rev. Prof. P. Mgeni - Ruaha Catholic University Dr A. B. G. Msigwa - University of Dar es Salaam Dr C. Asiimwe - Makerere University, Uganda Dr D. Goodness - Dar es Salaam University College of Education Dr D. O. Ochieng - The Open University of Tanzania Dr E. H. Y. Chaula - University of Iringa Dr E. Haulle - Mkwawa University College of Education Dr E. Tibategeza - St. Augustine University of Tanzania Dr F. Hassan - University of Dodoma Dr F. Tegete - Catholic University College of Mbeya Dr F. W. Gabriel - Ruaha Catholic University Dr M. Nassoro - State University of Zanzibar Dr M. P. Mandalu - Stella Maris Mtwara University College Dr W. Migodela - Ruaha Catholic University SECRETARIAL BOARD Dr Gerephace Mwangosi - Ruaha Catholic University Mr Claudio Kisake - Ruaha Catholic University Mr Rubeni Emanuel - Ruaha Catholic University The journal is published bi-annually by the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Ruaha Catholic University. ©Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Ruaha Catholic University. -

The Impact of Kenya National Library Services (KNLS), Kisumu Provincial Mobile Library Services on Education in Kisumu County,Kenya

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 2012 The Impact of Kenya National Library Services (KNLS), Kisumu Provincial Mobile Library Services On Education in Kisumu County,Kenya. James Macharia Tutu Maseno University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Tutu, James Macharia, "The Impact of Kenya National Library Services (KNLS), Kisumu Provincial Mobile Library Services On Education in Kisumu County,Kenya." (2012). Library Philosophy and Practice (e- journal). 879. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/879 THE IMPACT OF KNLS KISUMU PROVINCIAL MOBILE LIBRARY SERVICES ON EDUCATION IN KISUMU COUNTY Abstract The purpose of this study was to establish the impact of KNLS Kisumu provincial mobile library services on education in Kisumu County. Qualitative research approach was used to conduct the study. Interviews were used to collect data and data was analysed qualitatively. Ten schools were sampled for the study, six secondary schools and four primary schools. Personnel working with KNLS Kisumu provincial mobile library services and teachers in sampled schools were interviewed. The study established that the impact of KNLS Kisumu provincial mobile library services on education in Kisumu County was positive. The study recommends the diversification of the mobile library services by offering internet services. Key words: mobile libraries, Kenya National Library Services, education 1. Introduction and Background Information Mobile library is any kind of medium that takes books and other library items to people. This medium rages from vans, rivers and canals, trains, sacks, donkeys and camels. -

Advancing Africa's Sustainable Development Vii

Advancing Africa’s Sustainable Development Advancing Africa’s Sustainable Development: Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Science Advancement Edited by Alain L. Fymat and Joachim Kapalanga Advancing Africa’s Sustainable Development: Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Science Advancement Edited by Alain L. Fymat and Joachim Kapalanga This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Alain L. Fymat, Joachim Kapalanga and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0655-X ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0655-8 CONTENTS Foreword .................................................................................................. viii Acknowledgments ...................................................................................... xi Contributors .............................................................................................. xiv About the Editors ...................................................................................... xvi Preface ...................................................................................................... xix Abbreviations .......................................................................................... -

No. 1. Makhan Singh

Makhan Singh Every Inch A Fighter Reflections on Makhan Singh and the Trade Union Struggle in Kenya By Shiraz Durrani Presentation in Nairobi. Saturday August 3, 2013 Notes & Quotes Study Guide Series No. 1 (2014) Nairobi 1 Every Inch A Fighter Reflections on Makhan Singh and the Trade Union Struggle in Kenya By Shiraz Durrani Nairobi. Saturday August 3, 2013 Highlights of the presentation at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CByviTH5HC0&t=0s Notes & Quotes Study Guide Series No. 1 (2014) ISBN 978-1-869886-02-8 http://vitabooks.co.uk London. UK Photo: Makhan Singh, Nairobi, 1947. Photo by Gopal Singh Chandan a quote here.” 2 Every inch a fighter Reflections on Makhan Singh and the Trade Union Struggle in Kenya Nairobi. Saturday August 3, 2013 December this year will mark Makhan Singh's 100th birthday. To mark this anniversary and reflect on his life and contribution to Kenya’s liberation, Mau Mau Research Centre invites you to a lecture celebrating the life and work of Makhan Singh on 3rd August 2013 from 1.30pm to 4.00pm. The highlight of the day will be a presentation by our invited speaker, Shiraz Durrani titled: “Every inch a fighter Reflections on Makhan Singh and the trade union struggle in Kenya”. The lecture will take place at the Professional Centre, St John’s Gate, Parliament Road. This Study Guide is based on the presentation made at that event. Highlights of the event can be see on YouTube at the following link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CByviTH5HC0&t=0s 3 Life and times of Makhan Singh Born 27-12-1913, Gharjakh, India 1927: Came to Kenya 1931: Worked in printing press 1939: To India 1940-45: Detained in India 1947: Returned to Kenya 1950-61: Imprisoned in Kenya 4 Makhan Singh, the trade unionist March, 1935: elected Secretary of the Indian Trade Union; Aug 1949: President Influenced ITU to change to Labour Trade Union of Kenya: open it to workers irrespective of race, religion, colour.