From Dispossession to Display: Authenticity, Aboriginality and the Queensland Museum, C. 1862-1917

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf, 509.06 KB

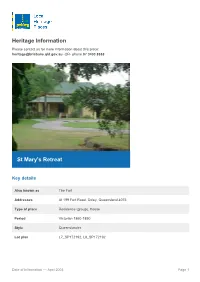

Heritage Information Please contact us for more information about this place: [email protected] -OR- phone 07 3403 8888 St Mary's Retreat Key details Also known as The Fort Addresses At 199 Fort Road, Oxley, Queensland 4075 Type of place Residence (group), House Period Victorian 1860-1890 Style Queenslander Lot plan L7_SP172192; L8_SP172192 Date of Information — April 2003 Page 1 Key dates Local Heritage Place Since — 1 January 2004 Date of Information — April 2003 Construction Roof: Corrugated iron; Walls: Timber People/associations Henry William Coxen and family (Occupant) Criterion for listing (A) Historical; (E) Aesthetic; (H) Historical association This house was built in the early 1880s for Henry William Coxen, one of the pioneering graziers in south-east Queensland. He established Jondaryan station on the Darling Downs and was Chairman of the Sherwood Division in 1902. From 1955-1962, this large property of 12.4 hectares was acquired by the Provincial of the Congregation of the Passion in Australasia. It is now used as a retreat centre and home for the Passionist Fathers in Queensland. History In 1865, Henry Coxen purchased 24 acres and 1 rood of riverfront land at Oxley with William Sim for £59 15s. In 1866, Coxen became the sole owner of the land. Coxen added to his property at Oxley in 1870 when he purchased an adjoining 8 acres, and again in 1883 when he purchased another eight acres of riverfront land. Coxen moved with his wife and four children to Oxley in 1880 when he was 57 years old. He probably built this house in the early 1880s, as he was Chairman of the Yeerongpilly Divisional Board (similar to a shire council) in 1887. -

Caleb Threlkeld's Family

Glasra 3: 161–166 (1998) Caleb Threlkeld’s family E. CHARLES NELSON Tippitiwitchet Cottage, Hall Road, Outwell, Wisbech, PE14 8PE, U. K. MARJORIE RAVEN 7 Griffin Avenue, Bexley, New South Wales 2207, Australia. INTRODUCTION The Revd Dr Caleb Threlkeld was the author of the first flora of Ireland (Nelson 1978, 1979; Doogue & Parnell, 1992), and a keen amateur botanist (Nelson, 1979, 1986). A native of Cumberland, Threlkeld was a physician by profession and a dissenting minister by vocation. He lived in Dublin from 3 April 1713 until his death on 28 April 1728. Hitherto biographical information about Caleb Threlkeld has been derived from contemporary parochial and university records, from his book Synopsis stirpium Hibernicarum (Threlkeld, 1726; Nelson & Synnott, 1998), and from biographies written many years after his death (Pulteney, 1777, 1790). Until the present authors, quite by chance, made contact no other sources were known to Irish and British scholars, but we now wish to draw attention to the existence of a manuscript containing substantial details of Threlkeld’s family in The Mitchell Library, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. In particular, the manuscript provides previously unavailable information about Caleb Threlkeld’s parents, wife, and children. THE THRELKELD MANUSCRIPT: history and contents The Mitchell Library manuscript, a book of 60 folios, was ‘found among the private papers of the Revd Lancelot Threlkeld, late of Premier Terrace, William Street, Sydney’, following his death on 10 October 1859.1 Lancelot Edward Threlkeld was descended from Joshua Threlkeld (b. 29 July 1673), an elder brother of the Irish botanist, the Revd Dr Caleb Threlkeld. -

Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession Around the Pacific Rim

Cambridge Imperial & Post-Colonial Studies INTIMACIES OF VIOLENCE IN THE SETTLER COLONY ECONOMIES OF DISPOSSESSION AROUND THE PACIFIC RIM EDITED BY PENELOPE EDMONDS & AMANDA NETTELBECK Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series Series Editors Richard Drayton Department of History King’s College London London, UK Saul Dubow Magdalene College University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK The Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies series is a collection of studies on empires in world history and on the societies and cultures which emerged from colonialism. It includes both transnational, comparative and connective studies, and studies which address where particular regions or nations participate in global phenomena. While in the past the series focused on the British Empire and Commonwealth, in its current incarna- tion there is no imperial system, period of human history or part of the world which lies outside of its compass. While we particularly welcome the first monographs of young researchers, we also seek major studies by more senior scholars, and welcome collections of essays with a strong thematic focus. The series includes work on politics, economics, culture, literature, science, art, medicine, and war. Our aim is to collect the most exciting new scholarship on world history with an imperial theme. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/13937 Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck Editors Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession around the Pacific Rim Editors Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck School of Humanities School of Humanities University of Tasmania University of Adelaide Hobart, TAS, Australia Adelaide, SA, Australia Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series ISBN 978-3-319-76230-2 ISBN 978-3-319-76231-9 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76231-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018941557 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 This work is subject to copyright. -

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook BA Hons (Trent), War Studies (RMC) This thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences UNSW@ADFA 2005 Acknowledgements Sir Winston Churchill described the act of writing a book as to surviving a long and debilitating illness. As with all illnesses, the afflicted are forced to rely heavily on many to see them through their suffering. Thanks must go to my joint supervisors, Dr. Jeffrey Grey and Dr. Steve Harris. Dr. Grey agreed to supervise the thesis having only met me briefly at a conference. With the unenviable task of working with a student more than 10,000 kilometres away, he was harassed by far too many lengthy emails emanating from Canada. He allowed me to carve out the thesis topic and research with little constraints, but eventually reined me in and helped tighten and cut down the thesis to an acceptable length. Closer to home, Dr. Harris has offered significant support over several years, leading back to my first book, to which he provided careful editorial and historical advice. He has supported a host of other historians over the last two decades, and is the finest public historian working in Canada. His expertise at balancing the trials of writing official history and managing ongoing crises at the Directorate of History and Heritage are a model for other historians in public institutions, and he took this dissertation on as one more burden. I am a far better historian for having known him. -

The Quest for Natural Biogeographic Regions

Chapter 3 Carving up Australasia: the quest for natural biogeographic regions Most systematists will squirm at inferences derived from a non-monophyletic or artificial taxon. The importance of monophyly is critical to understanding the natural world and drawing inferences about past processes and events. Since the early 19th century, plant and animal geographers have also been concerned about correctly identifying natural areas. Plant geographer and taxonomist Augustin de Candolle tried to propose natural laws when proposing natural areas and failed. Humboldt abandoned natural classification and assigned vegetable forms, thereby creating a useful classification, which was unfortunately artificial. For early 19th century Australasian biogeographers, the concept of cladistic biogeography and area monophyly was decades away, while the importance of finding natural areas was immediate. Natural areas allowed the biogeographer to make inferences about the biotic evolution of a region such as Australia or New Zealand. Discovering the relationships between natural areas would allow for better inferences about dispersal pathways and evolutionary connections between continental floras and faunas, rather than proposing ephemeral land-bridges or sunken continents. Still, after 150 years of searching, biogeographers puzzle over the natural regions of Australasia. Why natural regions? As in biological systematics, artificial taxa represent a pastiche of distantly related taxa (think of the term ‘insectivores’, which would include all insect eating animals, such as funnel-web spiders, bee-eaters and echidnas). Artificial taxa are more closely related to other taxa than they are to themselves. The same is true for biogeography – artificial areas, such as ‘Australia’, are composites that are more closely related to other areas than they are to themselves. -

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE a History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE A History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016 CONTENTS 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Romanesque Style . 4 3. Australian Romanesque: An Overview . 25 4. New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory . 52 5. Victoria . 92 6. Queensland . 122 7. Western Australia . 138 8. South Australia . 156 9. Tasmania . 170 Chapter 1: Introduction In Australia there are four Catholic cathedrals designed in the Romanesque style (Canberra, Newcastle, Port Pirie and Geraldton) and one Anglican cathedral (Parramatta). These buildings are significant in their local communities, but the numbers of people who visit them each year are minuscule when compared with the numbers visiting Australia's most famous Romanesque building, the large Sydney retail complex known as the Queen Victoria Building. God and Mammon, and the Romanesque serves them both. Do those who come to pray in the cathedrals, and those who come to shop in the galleries of the QVB, take much notice of the architecture? Probably not, and yet the Romanesque is a style of considerable character, with a history stretching back to Antiquity. It was never extensively used in Australia, but there are nonetheless hundreds of buildings in the Romanesque style still standing in Australia's towns and cities. Perhaps it is time to start looking more closely at these buildings? They will not disappoint. The heyday of the Australian Romanesque occurred in the fifty years between 1890 and 1940, and it was largely a brick-based style. As it happens, those years also marked the zenith of craft brickwork in Australia, because it was only in the late nineteenth century that Australia began to produce high-quality, durable bricks in a wide range of colours. -

Rare and Curious Specimens, an Illustrated

Having held the position in an acting capacity, Etheridge experienced no dif ficulty in assuming the full-time position of curator on 1 January 1895. He had, of course, to relinquish his half-time post in the Geological Survey but, as consulting palaeontologist to the Survey, he retained a foot in each camp and continued to publish under the aegis of both institutions. His scientific staff consisted of six men. Whitelegge was still active in his researches on marine invertebrates and was engaged in testing the efficiency of formalin as a preservative. North continued his studies on birds, but somewhat less actively since, to free Brazier for work on his long-delayed catalogue, he had been made responsible also for the ethnological, numismatic and historical collections. Conchology was now in the hands of Charles Hedley, first appointed in 1891 on a temporary basis to handle the routine matters of this department and to leave Brazier more time for his catalogue. Born in England, Hedley came to Australia at the age of twenty to seek relief from asthma and after a short period working on an oyster lease on Stradbroke Island, turned to fruit growing at Boyne Island. When a badly fractured left arm rendered him unfit for heavy work, he moved to Brisbane where, in 1889, he obtained a position on the staff of the Queensland Museum and developed an interest in shells. Finding that the collections and library of that insti tution were inadequate for his needs, he moved to Sydney and, within a few months, was recruited to the Museum at the age of thirty. -

Lennon Heritage Places in Queensland Heritage

Lennon Heritage places in Queensland Heritage Places in Queensland Jane Lennon For millennia people have left their mark on the land - scarred trees, handprints, rock art, shell middens. This urge to leave a sign of passing, of occupation, is strong in most cultures. These often accidental marks are today's heritage, the physical legacy of previous generations. From the historical date of some events and records of what happened on that date in a specific place, we can construct an account of its history. By examining the evidence left at the place as well as this record of history, we can determine its cultural significance to people today; that is, we create its heritage. A timeline of European events of historical significance to Queensland by century is presented in Appendix 1. The exploration of Terra Australis by mariners is the preoccupation of the first two centuries, until John Oxiey's survey in 1823. The convict era commenced in 1824 and ran until 1840, when free settlement brought an extensive if tenuous occupation to the southeast of today's Queensland and wider pastoral exploration began. After 30 years of European settlement, Brisbane was perceived as a 'sleepy hollow' and in 1854 there were complaints of dilapidated government buildings and services, but brick houses were being erected in North Quay and immigrants were establishing a thriving village in Fortitude Valley.^ By 1859 there were about 28,000 Queenslanders of European origin, half located in the country north to Rockhampton and half divided between Brisbane, Ipswich and smaller provincial towns. Following separation from New South Wales, the new colony set about establishing its mark in land surveys, marking out freehold, roads, railways and other utilitarian reserves. -

1993 Monash University Calendar Part 1

Monash University Calendar 1993 Part I- Lists of members Part II-Legislation Monash University Calendar is published in January each year and updated throughout the year as required. Amendments to statutes and regulations are only published following Council approva1 and promulgation. The Publishing Department must be advised throughout the year of all changes to staff listings on a copy of the 1993 Amendments to staff details form located in Part I and approved by the appropriate head of department. Caution The information contained in this Calendar is as correct as possible at the publication date shown on each page. See also the notes at the start of Part I and Part II. Produced by. Publishing Department, Office of University Development Edited by: David A. Hamono Inquiries: Extn 75 6003 Contents Part I- Lists of members Officers and staff Principal officers ................................. 1 Members of Council ............................. 1 The Academic Board ............................ 2 Emeritus professors .............................. 3 Former officers ................................... 5 The professors .................................... 8 Faculty of Arts .................................. 12 Faculty of Business ............................. 18 Faculty of Computing and Information Technology ................................... 21 Faculty of Economics Commerce and Management ................................. 24 Faculty of Education ........................... 27 Faculty of Engineering ......................... 29 Faculty -

1 Reflections on the Life and Ministry of the Revd. John Williams, Pioneer

Reflections on the life and ministry of the Revd. John Williams, pioneer missionary serving under the London Missionary Society 1816-1839 Brief Biography Born at Tottenham High Cross, London 27th June 1796 son of John Williams and Margaret Maidmeet. Educated at a school in Lower Edmonton. Apprenticed to a Mr Elias Tonkin ironmonger. Invited to attend Whitefield Tabernacle, City Road 1814 on suggestion of Mrs Tonkin. Applied to the Missionary Society 1815 for work in the South Seas Ordained at Surrey Chapel 30th Sept 1816. Married Mary Chawner Oct 29th 1816 Set off in the Harriet 17th Nov 1816. (to Sydney) Arrived in the Society Islands (Moorea) via Rio and the Cape Horn, Hobart and Sydney on Nov 17th 1817. From Sydney sailed in the Active. Served in the (Leeward) islands of Huahine and Raiatea with Rev. Lancelot Threlkeld. On the latter island he had encouragement from Tamatoa, chief of Raiatea. Williams was anxious to develop work in other groups of islands, but had no encouragement from the directors of the LMS. 1821 Travelled to Sydney for medical advice for himself and his wife. En route he lands native teachers on Aitutaki (the Hervey Islands – now part of the Cook Islands). Purchased ship the Endeavour. Travelled back to Raiatea. Ship renamed Te Matamua (“The Beginning”). 1822 Visited the Hervey Islands. Discovered Raratonga. Left Papeiha, a native Raiatean teacher on Rarotonga. Rurutu and Rimatara were visited later in the year. The Endeavour has to be sold. Williams’ next visit to the Herveys (1827) was by charted ship, also taking Rev. Charles and Mrs Elizabeth Pitman to Rarotonga. -

Australian Historians and Historiography in the Courtroom

Advance Copy AUSTRALIAN HISTORIANS AND HISTORIOGRAPHY IN THE COURTROOM T ANYA JOSEV* This article examines the fascinating, yet often controversial, use of historians’ work and research in the courtroom. In recent times, there has been what might be described as a healthy scepticism from some Australian lawyers and historians as to the respective efficacy and value of their counterparts’ disciplinary practices in fact-finding. This article examines some of the similarities and differences in those disciplinary practices in the context of the courts’ engagement with both historians (as expert witnesses) and historiography (as works capable of citation in support of historical facts). The article begins by examining, on a statistical basis, the recent judicial treatment of historians as expert witnesses in the federal courts. It then moves to an examination of the High Court’s treatment of general works of Australian history in aid of the Court making observations about the past. The article argues that the judicial citation of historical works has taken on heightened significance in the post-Mabo and ‘history wars’ eras. It concludes that lasting changes to public and political discourse in Australia in the last 30 years — namely, the effect of the political stratagems that form the ‘culture wars’ — have arguably led to the citation of generalist Australian historiography being stymied in the apex court. CONTENTS I Introduction .................................................................................................................. -

Lynette Russell – 'An Unpicturesque Vagrant': Aboriginal Victorians at The

Lynette Russell ‘An unpicturesque vagrant’: Aboriginal Victorians at the Melbourne International Exhibition 1880–1881* THE GRAND DAME of Melbourne architecture, the Royal Exhibition Building was the first non-Aboriginal cultural site in Australia awarded UNESCO World Heritage listing. In 2004, in Suzhou China, the UNESCO World Heritage Committee announced that the Royal Exhibition Building and surrounding Carlton Gardens qualified under cultural criterion (ii) of the Operational Guidelines for the implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Criterion (ii) lists sites that exhibit ‘an important interchange of human values, over a span of time or within a cultural area of the world, on developments in architecture or technology, monumental arts, town-planning or landscape design’.1 The Royal Exhibition Building does, however, have links to the Aboriginal community of Melbourne beyond being constructed on Kulin land. Contemporary Kulin connections are intensified by the proximity to the Melbourne Museum and Bunjilaka Aboriginal Cultural Centre. This article considers some evidence of Aboriginal presence at the Exhibition building during the Melbourne International Exhibition of 1880-81. The Exhibition building was famously built to house the Melbourne International Exhibition of 1880-81. Designed by architect Joseph Reed, the building was heralded as a magnificent achievement – indeed it was monumental, with its dome the tallest construction in the city. As Graeme Davison illustrated in his seminal study Marvellous Melbourne, our metropolis was, in the 1880s, a boom city; the International exhibition was to be a celebration of the city’s economic success, its technological and industrial achievements and all that was marvellous.2 The newspapers and magazines carried articles that exulted the enthusiasm and energy of the city along with the incredible optimism that characterised the 1880s boom.