Motion Picture, Became the Most Popular Form of Passive Recreation for Bay View Residents, Starting in 1905 When the Neighborhood's First Theater, the Comique, Opened

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rediscovering Milwaukee's Historic Breweries Part I: Milwaukee's Downtown Breweries Kevin M Cullen

Rediscovering Milwaukee's historic breweries Part I: Milwaukee's downtown breweries Kevin M Cullen When you mention Milwaukee, one asso- congregate in solidarity as we investigate ciation in particular comes to mind, beer. ancient and traditional alcoholic bever- This is because Milwaukee, Wisconsin ages around the world. Hence, it was a once boasted the largest production of logical and easy leap to get this eager beer than any other city in America and public on board to rediscover their own indeed the world. As an agricultural and city's brewing legacy. industrial hub on Lake Michigan for more than a century and a half with a thirsty Therefore, the first of what will be four population of ethnically proud beer ‘Legacies of Milwaukee Brewing’ tours lovers, Milwaukee was well poised to took place on 17 April 2010. It was decid- conquer the American brewing industry. ed given the breadth and scope of this What many people do not know however, city's brewing heritage, that we would is that this city has seen more than 100 focus our first tour on the historic and brewing companies come and go over contemporary breweries of downtown the past 170 years and unfortunately the Milwaukee. With Kalvin at the helm of a original breweries as well. full motor coach bus, Leonard Jurgensen as the Milwaukee brewery historian and I Therefore, as part of the Distant Mirror as the archaeological tour guide, we Archaeology Program at Discovery World made our way to one of Milwaukee's first (a science and technology museum in brewery sites at the end of Clybourn Milwaukee, Wisconsin) I am attempting Street (formerly Huron Street) and Lincoln to rediscover this brewing legacy through Memorial Drive (formerly the Lake urban archaeological expeditions. -

National Historic Landmark Nomination Northwestern

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NORTHWESTERN BRANCH, NHDVS Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Northwestern Branch, National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers Other Name/Site Number: Northwestern Branch, National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers Historic District; National Soldiers Home Historic District; Clement J. Zablocki Medical Center, Department of Veterans Affairs 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 5000 West National Avenue Not for publication: City/Town: Milwaukee Vicinity: State: WI County: Milwaukee Code: 079 Zip Code: 53295 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): ___ Public-Local: District: _X_ Public-State: ___ Site: ___ Public-Federal: ___ Structure: ___ Object: _X_ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 23 16 buildings 3 sites 2 2 structures 2 1 objects 30 19 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 31 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: DRAFT NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NORTHWESTERN BRANCH, NHDVS Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Communication Bulletin January, 2013 Volume 3

Communication Bulletin January, 2013 Volume 3 Prepared by: Christina Curran-Wurst National PR Director The intent of this bulletin is to convey news about the American Sokol 2013 Sports Festival taking place Tuesday, June 25 – Sunday, June 30 in Milwaukee, WI. This month, read about where to find the latest information, the first souvenir available for purchase, schedule update and addition, headquarter hotel room reservations and fun facts about Milwaukee. If you have questions or inquiries regarding the 2013 Sports Festival, send an email to [email protected]. Your email will be routed to the correct committee chairperson. Find the latest information at www.american-sokol.org Don’t be left out! The latest information is available on the American Sokol home page by clicking on the 2013 Sports Festival logo: Communication Bulletins o August 2012 o September 2012 o Bulletins not published Oct-Dec 2012 Promotional literature o Official Sports Festival poster o Schedule of Events rack card o 2013 Sports Festival presentation – use this to publicize the event to your organization, members, parents, and more! Instructional materials o 2013 Sports Festival manual o Flash Mob – perform a flash mob in your area to generate publicity! . Teaching video . Routine instructions . Performance instructions . Registration and release form Travel to Milwaukee o Discounted event hotel and rental cars Be sure to check it often for updates! American Sokol Organization • 9126 Ogden Ave. • Brookfield, IL 60513 708-255-5397 • www.american-sokol.org • [email protected] Communication Bulletin January, 2013 Volume 3 Prepared by: Christina Curran-Wurst National PR Director 2013 Sports Festival Pins for sale The first 2013 Sports Festival souvenir is available for purchase! Get the official pin today! Show your pride and promote the upcoming festival by wearing your pin to any and all events! Custom 1” round photo dome lapel pin. -

Doors Open Block Party See Inside Cover for Information

DOORS OPEN BLOCK PARTY SEE INSIDE COVER FOR INFORMATION Free access to 170+ buildings and 35+ tours across Milwaukee over 2 days. EXPLORE YOUR CITY! We have a new website— visit doorsopenmilwaukee.org to build your itinerary. Tripoli Shrine Center, photo by Jon Mattrisch, JMKE Photography A SPECIAL THANK YOU TO OUR PRESENTING SPONSOR, WELLS FARGO AND TO THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT OF THE ARTS, FOR RECOGNIZING DOORS OPEN WITH AN ART WORKS DESIGN GRANT. DOORS OPEN IS GRATEFUL FOR THE GENEROUS SUPPORT FROM OUR SPONSORS IN-KIND SPONSORS DOORS OPEN MILWAUKEE BLOCK PARTY & EVENT HEADQUARTERS East Michigan Street, between Water and Broadway (the E Michigan St bridge at the Milwaukee River is closed for construction) Saturday, September 28 and Sunday, September 29 PICK UP AN EVENT GUIDE ANY TIME BETWEEN 10 AM AND 5 PM BOTH DAYS ENJOY MUSIC WITH WMSE, FOOD VENDORS, AND ART ACTIVITIES FROM 11 AM TO 3 PM BOTH DAYS While you are at the block party, visit the Before I Die wall on Broadway just south of Michigan St. We invite the public to add their hopes and dreams to this art installation. Created by the artist Candy Chang, Before I Die is a global art project that invites people to contemplate mortality and share their personal aspirations in public. The Before I Die project reimagines how walls of our cities can help us grapple with death and meaning as a community. 2 VOLUNTEER Join hundreds of volunteers to help make this year’s Doors Open a success. Volunteers sign up for at least one, four-hour shift to help greet and count visitors at each featured Doors Open site throughout the weekend. -

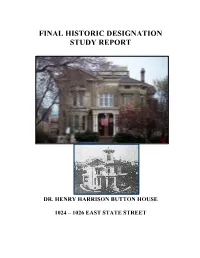

Final Historic Designation Study Report

FINAL HISTORIC DESIGNATION STUDY REPORT DR. HENRY HARRISON BUTTON HOUSE 1024 – 1026 EAST STATE STREET FINAL HISTORIC DESIGNATION STUDY REPORT HENRY H. BUTTON HOUSE (Written Fall, 2002) I. NAME Historic: Henry Harrison Button House Common: Button House/David Barnett Gallery II. LOCATION 1024-1026 E. State Street Legal Description: SUBD OF BLOCK 105 IN NW ¼ SEC 28-7-22 BLOCK 105 N 52’ LOT 6 & E 75’ (LOTS 7-8 & S 8’ LOT 6) 4th Aldermanic District Alderman Paul A. Henningsen III. CLASSIFICATION Structure IV. OWNER David J. Barnett 1024 E. State Street Milwaukee, WI 53202 NOMINATOR Susan Comstock V. YEAR BUILT 18751 ARCHITECT E. Townsend Mix2 VI. PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION The Henry Harrison Button House is located at the northwest corner of E. State Street and N. Waverly Place in what is known as the Yankee Hill Neighborhood. The house and grounds 1 Milwaukee Sentinel July 24, 1875 and December 31, 1875. 2 Ibid. 1 once occupied a spacious 180-foot by 127-foot parcel consisting of three lots. Today the property has been reduced to an L-shaped parcel dimensioned at roughly 180-feet by 75-feet by 128-feet by 52-feet by 52-feet. To the east of the house is Juneau Park and across from the house is a small green square bounded by E. State St., N. Astor St., N. Prospect Ave. and E. Kilbourn Ave. The neighborhood is characterized by a mix of 19th century houses and mansions dating mostly from the 1870’s through the 1890’s, early 20th century apartment buildings, and 19th century churches. -

A Guide From

1 - 0;% 9 / ) ) - 2 1 - 2 - %8 9 6 ) A Guide From: We welcome you to tour historic Milwaukee as it was in the early 1900s. Through the miniature models of Ferdinand Aumueller, seen at the Milwaukee County Historical Society, the architectural treasures of Milwaukee come to life, telling the story of a city rich in history. Now see these landmarks as they are today on this self-guided tour of historic Milwaukee. View the sites where these buildings once stood, as well as some of the buildings that are still standing. Through this self-guided tour you will learn about Milwaukee’s past as you tour Milwaukee’s present. = Exposition Building = Pabst Building = Germania Building = North Broadway = Republican House = Mitchell & Mackie Buildings = Schlitz Hotel & Palm Garden = Layton Art Gallery = 2nd Ward Savings Bank = Pabst Theater = Public Service Building = Milwaukee County Courthouse = Milwaukee River = City Hall = Gimbels = Milwaukee Road Depot Exposition Building Story Architect: Edward Townsend Mix; Constructed Contractor: Charles Kockhefer Jr. Milwaukeeís first Industrial Exposition, 1880 - 1881 featuring the slogan ìMake Milwaukee Mighty,î arrived in 1881 and showcased Architectural Style: local innovation in industry, arts, and culture. The event took place in Queen Ann the Exposition Building, created by the Milwaukee Industrial Exposition Commission. During the exposition, Construction Materials: over 145,000 visitors came from all over Brick, Metal, Glass the country to see products from all disciplines of industry and art. Dimensions: Following its inaugural year, the 400x 290; 100 feet high at main entrance; dome was Exposition Building was at the epicenter 226 feet high of a myriad of other events, both social and somber. -

The Renaissance Historic Third Ward

OFFICE SPACE FOR LEASE The Renaissance Historic Third Ward R THE RENAISSANCE 1,000-7,000 RSF Starting at $17.00 PSF 309 N. Water Street Milwaukee, WI 53202 THE RENAISSANCE is the crown jewel of Milwaukee’s Historic Third Ward, conveniently located just south of I-794 in downtown Milwaukee at the corner of Water and Buffalo Streets. Constructed in 1896, with extensive renovations completed in 2003, this seven-story mixed-use office building features exposed timber, original cream city brick, and an optimal blend of neighborhood amenities and services. LOCATION OVERVIEW Milwaukee’s Historic Third Ward Located in the heart of the Historic Third Ward, The Renaissance is a premier office location central to over 50 restaurants, high-end boutiques, and a diverse array of businesses. The Third Ward is known as Milwaukee’s arts and fashion district and is home to the award-winning Third Ward Riverwalk and Milwaukee Public Market. Neighborhood features include: • Headquarters for numerous local and international businesses • Proactive and engaged Historic Third Ward Association manages Building Amenities an array of neighborhood events throughout the year • 1,000-7,000 RSF prime custom-designed and/or move-in ready office space with • The Henry W. Maier Festival Park frontage on the Milwaukee Riverwalk is the site for a rotating line-up of • Convenient location just south of I-794 special events from spring to fall, and downtown Milwaukee and east of the including ethnic festivals and the Milwaukee River world’s largest music festival, Summerfest -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No%0-300 >) .'\0' f* fl /) (0 \0 5 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 1 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC Walker's Point Historic District i AND/OR COMMON Walker's Point Historic District LOCATION STREET & —NOFRPUB LI CATION ' ' * / 3 - ' - CITY. TOV\lN j ... , , »" CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT 1 Milwaukee . Fourth .VICINITY OF STATE CODE ; COUNTY CODE Wisconsin 55 Milwaukee 079 ,/' QCLA SSIFI C ATI ON i CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED ^COMMERCIAL X-PARK — STRUCTURE " 2?BOTH _WORK IN PROGRESS XEDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE -.-ENTERTAINMENT X-RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _(N PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED -^.GOVERNMENT ^SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED ..-_YES: UNRESTRICTED ^.INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Multiple• . ownership. STREET & NUMBER, CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF [LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEos,ETc. Milwaukee County Courthouse - Recorder of Deeds STREET& NUMBER 901 North Ninth Street CITY. TOWN STATE Milwaukee Wisconsin 53233 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Wisconsin Inventory of Historic Places DATE 1971 —FEDERAL ^STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS State Historical Society of Wisconsin CITY. TOWN STATE Madison Wisconsin 53706 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE —GOOD _RLJINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED Located approximately a mile west of Lake Michigan and a mile south of Milwaukee's commercial center, the Walker's Point Historic District is situated on flat land elevated about twenty feet above Lake Michigan. -

The Mark of Mix B Y C H R Is S Z C Z Esny-Adams

g a lleria Mix’s “Old Main,” the landmark building of the National Soldiers Home in Milwaukee, designed in 1867. It was built to house nearly 1,000 veterans. Image from John G. Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin (1931) THE MARK OF MIX B Y C H R IS S Z C Z ESNY-ADAMS Villa Louis in Prairie du Chien and dward Townsend Mix (1831–1890) rose to prominence in 19th-century the Soldiers Home and the Mitchell E American architecture through his design versatility, keen insight, and Building in Milwaukee are just a few personal expression. Mix was a handsome gentleman with cultured tastes, refined of the distinctive buildings designed perceptions, and engaging manners. He by architect E. Townsend Mix. The first established himself in the Midwest prior to the rise of the Chicago School, the exhibition of his work is on display White City, the Prairie style, and their famous architects: Daniel Burnham, John Edward Townsend Mix through August 16 at the Monroe W. Root, Louis Sullivan, and Frank Lloyd Photo courtesy Milwaukee County Historical Society Wright. Yet Mix designed more than 300 Arts Center, a building Mix originally known structures from New York to Nebraska and revolutionized designed as a church in 1869. the Midwest with his sophisticated architecture, creating a reputa- tion as an architect of distinction. WISCONSIN PE O P L E & I DEAS SPR I N G 2 0 0 8 33 g a lleria “Old Main” tower, National Soldiers Home (detail) Photos by Chris Szczesny-Adams The Monroe Arts Center was built as the First Methodist Church. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME HISTORIC Day, Dt% FIsk HoTbrook, House LOCATION 8000STREET West & NUMBERMilwaukee Avenue _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Wauwatosa VICINITY OF Fourth STATE CODE CODE Wisconsin 55 Milwaukee 079 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC -XOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM XBUILDING(S) _>PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Miss Florence Rust STREET & NUMBER 3D?Fi VJpqt. Highland Boulevard CITY. TOWN STATE Milwaukee VICINITY OF Wisconsin 53208 ! LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDs.ETc. Milwaukee County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER 901 North Ninth Street CITY. TOWN STATE Milwaukee Wisconsin 53233 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Wisconsin Inventory of Historic Places DATE 1976 v —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS State Historical Society of Wisconsin CITY. TOWN STATE S QT1 Wisconsin DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED .JDRIGINAL SITE —GOOD —RUINS -ALTERED —MOVED DATE______ —X-FAIR — UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Day house is a two-and-one-half story Victorian eclectic structure set on the largest (1.62 acres) residential lot in the city of Wauwatosa. It is set back 194.79 feet from the lot line and is sited on the high point of a gently sloping hill. -

National Register of Historic Places \ Registration Form

NFS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (January 1992) Wisconsin Word Processing Format (Approved 192) United States Department of Interior National Park Service __ W*V_JL/ National Register of Historic Places \ Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties an5 districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900A). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property____________________________________________ historic name Wisconsin Leather Company Building____________________________________ other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number 320 East Clyboura Street N/A not for publication city or town Milwaukee N/A vicinity state Wisconsin ____code WI county Milwaukee code 079 zip code 53202 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering -

Landmarks/Buildings Collection Call Number: Mss-1887 Bulk

Title: Landmarks/Buildings Collection Call Number: Mss-1887 Bulk: 3.6 cu. ft. Location: LM, Sh. 038-040 Abstract: The collection contains materials relating to landmarks and buildings in Milwaukee County. Some material relates to the Madison area and Wisconsin. The materials are organized by specific landmark or building, historic district or miscellaneous materials. See Also: Ernst Kronshage Collection, Mss-2166 Mary Ellen Young, Mss-2255 Administrative Info: The collection was processed by Nicolas L. Neylon in July 1992. It was revised by Janet Geronime in November 1994, by Steve Daily in 1996 and 1997, by Mary Ann Dyer in 1997, by Kevin Abing in February 2000 and 2001, and by Amanda Wynne in June 2009. Landmark/Building Box # Folder # A.O. Smith Research Building 1 A Abel-Decker Row House, 408-410 S 3rd St 1 A Abbot Row 1 A All Saints’ Episcopal Cathedral 1 A Allen-Bradley Building 1 A Allis-Chalmers Clubhouse (SueShar’s) 1 A Alexander Stewart House 1 A Amador-Almeda Apartments 1 A1 Ambassador Hotel 1 A American House Hotel 1 A Amtrak Station/Intermodel 1 A Angus Smith Home 1 A Annason Apartments 1 A Arena/Auditorium 1 A Astor On The Lake 1 A Astor St. Row Houses, 1225-1231 N. Astor St. 1 A Athenaeum 1 A Atlas Apartments 211 W. North Ave. 1 A Arthur Tess Service Station 2202 W Grrenfield Ave. 1 A Bank of Milwaukee Building 1 B1 Bank One Plaza 1 B Baumann-Chase, House, 421 N Pinecrest 1 B Baumbach Building 1 B Bay View Library 1 B Bay View Terrace 1 OS SM L Bertelson Building 1 B Blatz Brewery 1 B3 Blatz Hotel 1 B Blatz, The (Apartments) 1 B2 Blatz, Val, House 1 B Blessed Virgin of Pompeii Catholic Church 1 B4 Bluemel’s Florist and Garden Service 1 B Bogk, Frederick C., House 1 B Borchert Field 1 B Boston Lofts (Boston Store Building) 1 B Bradley Center 1 B5 Brandt House 1 B6 Bresler, F.