Texas Indian Papers, 1825-1843 1 Illustrations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Tennessee

SECTION VI State of Tennessee A History of Tennessee The Land and Native People Tennessee’s great diversity in land, climate, rivers, and plant and animal life is mirrored by a rich and colorful past. Until the last 200 years of the approximately 12,000 years that this country has been inhabited, the story of Tennessee is the story of its native peoples. The fact that Tennessee and many of the places in it still carry Indian names serves as a lasting reminder of the significance of its native inhabitants. Since much of Tennessee’s appeal for settlers lay with the richness and beauty of the land, it seems fitting to begin by considering some of the state’s generous natural gifts. Tennessee divides naturally into three “grand divisions”—upland, often mountainous, East Tennessee; Middle Tennessee, with its foothills and basin; and the low plain of West Tennessee. Travelers coming to the state from the east encounter first the lofty Unaka and Smoky Mountains, flanked on their western slope by the Great Valley of East Tennessee. Moving across the Valley floor, they next face the Cumberland Plateau, which historically attracted little settlement and presented a barrier to westward migration. West of the Plateau, one descends into the Central Basin of Middle Tennessee—a rolling, fertile countryside that drew hunters and settlers alike. The Central Basin is surrounded on all sides by the Highland Rim, the western ridge of which drops into the Tennessee River Valley. Across the river begin the low hills and alluvial plain of West Tennessee. These geographical “grand divisions” correspond to the distinctive political and economic cultures of the state’s three regions. -

Stephen F. Austin and the Empresarios

169 11/18/02 9:24 AM Page 174 Stephen F. Austin Why It Matters Now 2 Stephen F. Austin’s colony laid the foundation for thousands of people and the Empresarios to later move to Texas. TERMS & NAMES OBJECTIVES MAIN IDEA Moses Austin, petition, 1. Identify the contributions of Moses Anglo American colonization of Stephen F. Austin, Austin to the colonization of Texas. Texas began when Stephen F. Austin land title, San Felipe de 2. Identify the contributions of Stephen F. was given permission to establish Austin, Green DeWitt Austin to the colonization of Texas. a colony of 300 American families 3. Explain the major change that took on Texas soil. Soon other colonists place in Texas during 1821. followed Austin’s lead, and Texas’s population expanded rapidly. WHAT Would You Do? Stephen F. Austin gave up his home and his career to fulfill Write your response his father’s dream of establishing a colony in Texas. to Interact with History Imagine that a loved one has asked you to leave in your Texas Notebook. your current life behind to go to a foreign country to carry out his or her wishes. Would you drop everything and leave, Stephen F. Austin’s hatchet or would you try to talk the person into staying here? Moses Austin Begins Colonization in Texas Moses Austin was born in Connecticut in 1761. During his business dealings, he developed a keen interest in lead mining. After learning of George Morgan’s colony in what is now Missouri, Austin moved there to operate a lead mine. -

Free Land Attracted Many Colonists to Texas in 1840S 3-29-92 “No Quitting Sense” We Claim Is Typically Texas

“Between the Creeks” Gwen Pettit This is a compilation of weekly newspaper columns on local history written by Gwen Pettit during 1986-1992 for the Allen Leader and the Allen American in Allen, Texas. Most of these articles were initially written and published, then run again later with changes and additions made. I compiled these articles from the Allen American on microfilm at the Allen Public Library and from the Allen Leader newspapers provided by Mike Williams. Then, I typed them into the computer and indexed them in 2006-07. Lois Curtis and then Rick Mann, Managing Editor of the Allen American gave permission for them to be reprinted on April 30, 2007, [email protected]. Please, contact me to obtain a free copy on a CD. I have given a copy of this to the Allen Public Library, the Harrington Library in Plano, the McKinney Library, the Allen Independent School District and the Lovejoy School District. Tom Keener of the Allen Heritage Guild has better copies of all these photographs and is currently working on an Allen history book. Keener offices at the Allen Public Library. Gwen was a longtime Allen resident with an avid interest in this area’s history. Some of her sources were: Pioneering in North Texas by Capt. Roy and Helen Hall, The History of Collin County by Stambaugh & Stambaugh, The Brown Papers by George Pearis Brown, The Peters Colony of Texas by Seymour V. Conner, Collin County census & tax records and verbal history from local long-time residents of the county. She does not document all of her sources. -

Traditional Caddo Stories—7Th Grade

Caddo Traditional Stories Personal Thoughts: My experience this past summer at the workshop and camping down the road at Mission Tejas State Park reinvigorated a personal connection to history. Most authors of history have been men. So, the word history, is simply restated as his story. The collection of oral stories was a tremendous task for early scholars. Winners of conflicts were often the ones to write down the tales of soldiers and politicians alike. Tales of everyday life were equally complex as the tales of battle. With Caddo stories, the main characters were often based on animals. So, a Caddo story can be a historical narrative featuring the environment, culture, and time period. The sounds of nighttime crawlers of the 21st century are the same sounds heard by the Caddo of Caddo Mounds State Historic Site. The nighttime sky above the forests of pine, pecan, and oak is the same as back then. The past is all around us, we just have to take it in. About This Lesson General Citation This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration files for Caddo Mounds State Historic Site (also known as the George C. Davis site) and materials prepared by the Texas Historical Commission. It was written by Kathy Lathen, a Texas educator with over a decade of classroom instructional experience. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country. Where is fits into Curriculum Topics and Time Period: This lesson could be incorporated with the Texas history unit on the historical era, Natural Texas and Its People (Prehistory to 1528). -

The Caddo After Europeans

Volume 2016 Article 91 2016 Reaping the Whirlwind: The Caddo after Europeans Timothy K. Perttula Heritage Research Center, Stephen F. Austin State University, [email protected] Robert Cast Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Cite this Record Perttula, Timothy K. and Cast, Robert (2016) "Reaping the Whirlwind: The Caddo after Europeans," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 2016, Article 91. https://doi.org/10.21112/.ita.2016.1.91 ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2016/iss1/91 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Regional Heritage Research at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reaping the Whirlwind: The Caddo after Europeans Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This article is available in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2016/iss1/91 -

Onetouch 4.6 Scanned Documents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1. Native Empires in the Old Southwest . 20 2. Early Native Settlers in the Southwest . 48 3. Anglo-American Settlers in the Southwest . 76 4. Early Federal Removal Policies . 110 5. Removal Policies in Practice Before 1830 . 140 6. The Federal Indian Commission and the U.S. Dragoons in Indian Territory . .181 7. A Commission Incomplete: The Treaty of Camp Holmes . 236 8. Trading Information: The Chouteau Brothers and Native Diplomacy . 263 Introduction !2 “We presume that our strength and their weakness is now so visible, that they must see we have only to shut our hand to crush them” - Thomas Jefferson to William Henry Harrison, February 27, 1803 Colonel Henry Dodge of the U.S. dragoons waited nervously at the bottom of a high bluff on the plains of what is now southwestern Oklahoma. A Comanche man on a white horse was barreling down the bluff toward Dodge and the remnants of the dragoon company that stood waiting with him. For weeks the dragoons had been wandering around the southern plains, hoping to meet the Comanches and impress them with the United States’ military might. However, almost immediately after the dragoon company of 500 men had departed from Fort Gibson in June 1834, they were plagued by a feverish illness and suffered from the lack of adequate provisions and potable water. When General Henry Leavenworth, the group’s leader, was taken ill near the Washita River, Dodge took command, pressing forward in the July heat with about one-fifth of the original force. The Comanche man riding swiftly toward Dodge was part of a larger group that the dragoons had spotted earlier on the hot July day. -

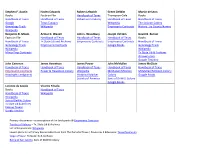

Stephen F. Austin Books

Stephen F. Austin Haden Edwards Robert Leftwich Green DeWitt Martin de Leon Books Facts on File Handbook of Texas Thompson-Gale Books Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Robertson’s Colony Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Google Texas Escapes Wikipedia The DeLeon Colony Genealogy Trails Wikipedia Empresario Contracts History…by County Names Wikipedia Benjamin R. Milam Arthur G. Wavell John L. Woodbury Joseph Vehlein David G. Burnet Facts on File Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Books Handbook of Texas Tx State Lib and Archives Empresario Contracts Empresario Contracts Handbook of Texas Genealogy Trails Empresario Contracts Google Books Genealogy Trails Wikipedia Wikipedia Minor Emp Contracts Tx State Lib & Archives Answers.com Google Timeline John Cameron James Hewetson James Power John McMullen James McGloin Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Empresario Contracts Power & Hewetson Colony Wikipedia McMullen/McGloin McMullen/McGloin Colony Headright Landgrants Historical Marker Colony Google Books Society of America Sons of DeWitt Colony Google Books Lorenzo de Zavala Vicente Filisola Books Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Wikipedia Wikipedia Sons of DeWitt Colony Tx State Lib & Archives Famous Texans Google Timeline Primary documents – transcriptions of the land grants @ Empresario Contracts Treaties of Velasco – Tx. State Lib & Archives List of Empresarios: Wikipedia Lesson plans for a Primary Source Adventure from The Portal of Texas / Resources 4 Educators: Texas Revolution Siege of Bexar: Tx State Lib & Archives Battle of San Jacinto: Sons of DeWitt Colony . -

Anson Jones and the Diplomacy of Texas Anneation

379l /. ~ ANSON JONES AND THE DIPLOMACY OF TEXAS ANNEATION THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 13y Ralph R. Swafford, B.S.E. Denton, Texas January, 1961 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. EARLY POLITICAL AND DIPLOMATIC CAREER . .... M .... II. ANSON JONES, SECRETARY OF STATE . 14 III. INDEPENDENCE ORANNZXATION . 59 IV. ANNEXATION ACHIEVEI.V. .!.... 81 V* ASSESSMENT . 91 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 101 Ii CHAPTER I EARLY POLITICAL AND DIPLOMATIC CAREER Because of the tremendous hardships and difficulties found in early Texas, one would suppose that the early Anglo- American pioneers were all hardy adventurers. Although many early Texans were of this variety, some were of a more gentle, conservative nature. Anson Jones, a man in the latter category, was not the type one usually pictures as a pioneer. He was a New Englander with a Puritan streak in his blood which almost seemed out of place in early Texas. 1 His yearning for power and prestige, coupled with a deep bitterness inherited from childhood, combined to give Jones an attitude that destined him for an unhappy existence and helps explain many of his caustic remarks concerning his associates. In all of his writings he has a definite tendency to blame others for fail- ures and give himself credit for the accomplishments. When Anson Jones referred to his early life, these references were usually filled with bitterness and remorsefulness. According to Jones, his home life was extremely dismal and bleak, and he blamed his family for some of his early sorrow.2 1 Herbert Gambrell, Anson Jones, The Last President of Texas (Garden City, N. -

Italian and Irish Contributions to the Texas War for Independence

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 23 Issue 2 Article 7 10-1985 Italian and Irish Contributions to the Texas War for Independence Valentine J. Belfiglio Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Belfiglio, alentineV J. (1985) "Italian and Irish Contributions to the Texas War for Independence," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 23 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol23/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 28 EAST TEXAS mSTORICAL ASSOCIATION ITALIAN AND IRISH CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE TEXAS WAR FOR INDEPENDENCE by Valentine J. Belfiglio The Texas War for Independence erupted with the Battle of Gon zales on October 2, 1835.' Centralist forces had renounced the Mex ican constitution and established a dictatorship. The Texas settlers, meanwhile, developed grievances. They desired to retain their English language and American traditions, and feared that the Mex ican government would abolish slavery. Texans also resented Mex ican laws which imposed duties on imported goods, suspended land contracts, and prohibited American immigration. At first the Americans were bent on restoring the constitution, but later they decided to fight for separation from Mexico. Except for research by Luciano G. Rusich (1979, 1982), about the role of the Marquis of " Sant'Angelo, and research by John B. -

Mary Jones: Last First Lady of the Republic of Texas

MARY JONES: LAST FIRST LADY OF THE REPUBLIC OF TEXAS Birney Mark Fish, B.A., M.Div. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2011 APPROVED: Elizabeth Hayes Turner, Major Professor Richard B. McCaslin, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History D. Harland Hagler, Committee Member Denis Paz, Committee Member Sandra L. Spencer, Committee Member and Director of the Women’s Studies Program James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Fish, Birney Mark. Mary Jones: Last First Lady of the Republic of Texas. Doctor of Philosophy (History), December 2011, 275 pp., 3 tables, 2 illustrations, bibliography, 327 titles. This dissertation uses archival and interpretive methods to examine the life and contributions of Mary Smith McCrory Jones in Texas. Specifically, this project investigates the ways in which Mary Jones emerged into the public sphere, utilized myth and memory, and managed her life as a widow. Each of these larger areas is examined in relation to historiographicaly accepted patterns and in the larger context of women in Texas, the South, and the nation during this period. Mary Jones, 1819-1907, experienced many of the key early periods in Anglo Texas history. The research traces her family’s immigration to Austin’s Colony and their early years under Mexican sovereignty. The Texas Revolution resulted in her move to Houston and her first brief marriage. Following the death of her husband she met and married Anson Jones, a physician who served in public posts throughout the period of the Texas Republic. Over time Anson was politically and personally rejected to the point that he committed suicide. -

Archaeological Findings from an Historic Caddo Site (41AN184) in Anderson County, Texas

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SFA ScholarWorks Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State Volume 2010 Article 24 2010 Archaeological Findings from an Historic Caddo Site (41AN184) in Anderson County, Texas Timothy K. Perttula Center for Regional Heritage Research, Stephen F. Austin State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Repository Citation Perttula, Timothy K. (2010) "Archaeological Findings from an Historic Caddo Site (41AN184) in Anderson County, Texas," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 2010 , Article 24. https://doi.org/10.21112/.ita.2010.1.24 ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2010/iss1/24 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Archaeological Findings from an Historic Caddo Site (41AN184) in Anderson County, Texas Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This article is available in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2010/iss1/24 Archaeological Findings from an Historic Caddo Site (41AN184) in Anderson County, Texas Timothy K. -

Chapter 12: the Lone Star Republic

RepublicThe of Te x a s 1836–1845 Why It Matters As you study Unit 4, you will learn about Texas as a republic. After the creation of the United States from the original 13 colonies, other territories were granted statehood. Only Texas entered the union as a separate and independent nation. The distinctive nature of Texas owes much to its having been a republic before it was a state and to the influence of its settlers. Primary Sources Library See pages 690–691 for primary source readings to accompany Unit 4. Going Visiting by Friedrich Richard Petri (c. 1853) from the Texas Memorial Museum, Austin, Texas. Socializing with neighbors was an important part of community life during the years of the republic. Not all Texas settlers wore buckskin and moccasins as this well-dressed family shows. 264 “Times here are easy… money plenty, the people much better satisfied.” —Dr. Ashbel Smith, December 22, 1837 GEOGRAPHY&HISTORY RICH HERITAGE There are many reasons why people take the big step of leaving their homes and moving to an unknown land— and Texas, during the years 1820 to 1860, witnessed all of them. The newly arriving immigrant groups tended to set- tle in one particular area, since it was easier to work with and live around people who spoke the same language and practiced the same customs. Many Mexicans came north while Texas was still a Spanish territory to set up farms on the fertile Coastal Plains. As A traditional band plays lively German the United States grew, more Native Americans, who had music at the Texas Folklife Festival.