Mumbai Human Development Report 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Office of the Commissioner of Police, Mumbai - 1

Office of the Commissioner of Police, Mumbai - 1 - I N D E X Section 4(1)(b) I to XVII Topic B) Information given on topics Page No. Nos. The particulars of the Police Commissionerate organization, functions I 2 – 3 & duties II The Powers and duties of officers and employees 4 – 8 The procedure followed in decision-making process including channels of III 9 supervision and accountability. IV The norms set for the discharge of functions 10 The rules, regulations, instructions manuals and records held or used by V 11-13 employees for discharging their functions. VI A statement of categories and documents that are held or under control 14 The Particulars of any arrangement that exists for consultation with or VII representation by the members of the public in relation to the formulation 15 of policy or implementation thereof; A statement of the boards, councils, committees and bodies consisting of two or more persons constituted as its part for the purpose of its advice, VIII and as to whether meetings of those board, councils, committees and other 16 bodies are open to the public, or the minutes of such meetings are accessible for public; IX Directory of Mumbai Police Officials -2005. 17-23 The monthly remuneration received by each of the officers and X employees including the system of compensation as provided in the 24 regulations. The budget allocated to each agency, indicating the particulars of all plans 25-31 XI proposed, expenditures and reports of disbursements made; The manner of execution of subsidy programmes, including the amounts -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

4.31 History (Paper-I)

Enclosure to Item No. 4.31 A.C. 25/05/2011 UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI Syllabus for the F.Y.B.A. Program : B.A. Course : History (Paper-I) (History of Modern Maharashtra 1848-1960 AD) (Credit Based Semester and Grading System with effect from the academic year 2011‐2012) 1. Syllabus as per Credit Based Semester and Grading System. i. Name of the Programme - B.A. ii. Course Code ‐ iii. Course Title - History (Paper-I) (History of Modern Maharashtra 1848-1960 AD) iv. Semester wise Course Contents - As per Syllabus v. References and additional references ‐ Submitted already vi. Credit structure - 3 Semester-I & 3 Semester-II vii. No. of lectures per Unit - 11,11,11 & 12 = 45 viii. No. of lectures per week / semester - 45 lectures per semester 2. Scheme of Examination ‐ 4 questions of 15 marks each internal & semester end. 3. Special notes, if any ‐ As per University Norms 4. Eligibility, if any ‐ As per University Norms 5. Free Structure ‐ As per University Norms 6. Special Ordinances / Resolutions, if any ‐ History of Modern Maharashtra (1848-1960) Semester End Examination 60 marks and Internal assessment 40 marks =100 marks per semester The Course should be completed / Covered/Taught in 45 (forty-five) Lectures (45) learning hours for Students) per Semester. In addition to this the student required to spend same number of hours (45) on self study in Library and / or institution or at home, on case study, writing journal, assignment, project etc to complete the course. The total credit value of this course is (03) three credits 45 teaching hours plus 45 hours self study of the student). -

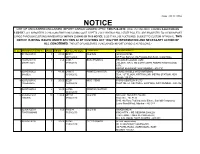

NOTICE LIST of UNCLEARED/UNCLAIMED IMPORT CARGO LANDED UPTO 18Th Feb 2014 to BE PUT in FORTH-COMING E-AUCTION on 12/01/17

Date : 20.12.2016 NOTICE LIST OF UNCLEARED/UNCLAIMED IMPORT CARGO LANDED UPTO 18th Feb 2014 TO BE PUT IN FORTH-COMING E-AUCTION ON 12/01/17. ALL IMPORTERS / CHA CONCERNED INCLUDING GOVT. DEPTTS. / ALL CENTRAL PSU / STATE PSU, ETC. ARE REQUESTED TO CLEAR IMPORT CARGO THROUGH CUSTOMS IMMEDIATELY WITHIN 15 DAYS OF THIS NOTICE; ELSE IT WILL BE AUCTIONED SUBJECT TO CUSTOM APPROVAL. THIS NOTICE IS BEING ISSUED UNDER SECTION 48 OF CUSTOMS ACT 1962 FOR INFORMATION AND NECESSARY ACTION OF ALL CONCERNED. THE LIST OF UNCLEARED / UNCLAIMED IMPORT CARGO IS AS FOLLOWS:- Sr.no MAWBNO/HAWB No PKGS GRWT FLT No/Flt Date COMMODITY CONSIGNEEADDRESS 1 08172652790 1 28.50 QF051 CLOTHS ILYAS A PATEL 29/11/2009 AT Post- Samrod, Via-Palsana,Dist-Surat, Gujrat State. 2 16034297410 1 2.50 CX017 ELECTRONICS RELIANCE GLOBAL COM 4051918449 09/05/2012 J BLOCK, GATE NO 4,DHIRUBHAI AMBANI KNOWLEDGE CITY, KOPAR KHAIRANE, NAVI MUMBAI - 400 710 3 02045005822 3 41.30 LH8370 PRINTED MATTER YOUNG ANGELS INTERNATIONAL 0469925 13/09/2012 70-A, 1ST FLOOR, KIRTI NAGAR, METRO STATION ,NEW DELHI- 110 015. 4 62072925300 3 20.00 BZ201 MISC ITEMS FIGRO GEOTECH P LTD 7855850645 15/09/2012 PLOT NO. 51, SECTOR 6, SANPADA, NAVI MUMBAI - 400 705. 5 02057045763 2 14.00 LH756 PRINTED MATTER 08/03/2010 6 23260621234 10 142.00 MH194 CLOTHS NEELAM HOSIERY HOUSE 1004006 09/04/2010 Kind Attn :- Mr. Punit B-45, 4th Floor,Todi Industrial Estate, Sun Mill Compound, Lower Parel(West), Mumbai - 400 013 7 02368352793 1 1.00 FX5034 CLOTHS GRAZIA INDIA 798515960440 31/03/2010 KIND ATTN :- MS. -

Transport in India Transport in the Republic of India Is an Important

Transport in India Transport in the Republic of India is an important part of the nation's economy. Since theeconomic liberalisation of the 1990s, development of infrastructure within the country has progressed at a rapid pace, and today there is a wide variety of modes of transport by land, water and air. However, the relatively low GDP of India has meant that access to these modes of transport has not been uniform. Motor vehicle penetration is low with only 13 million cars on thenation's roads.[1] In addition, only around 10% of Indian households own a motorcycle.[2] At the same time, the Automobile industry in India is rapidly growing with an annual production of over 2.6 million vehicles[3] and vehicle volume is expected to rise greatly in the future.[4] In the interim however, public transport still remains the primary mode of transport for most of the population, and India's public transport systems are among the most heavily utilised in the world.[5] India's rail network is the longest and fourth most heavily used system in the world transporting over 6 billionpassengers and over 350 million tons of freight annually.[5][6] Despite ongoing improvements in the sector, several aspects of the transport sector are still riddled with problems due to outdated infrastructure, lack of investment, corruption and a burgeoning population. The demand for transport infrastructure and services has been rising by around 10% a year[5] with the current infrastructure being unable to meet these growing demands. According to recent estimates by Goldman Sachs, India will need to spend $1.7 Trillion USD on infrastructure projects over the next decade to boost economic growth of which $500 Billion USD is budgeted to be spent during the eleventh Five-year plan. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

E-Bulletin Library and Documentation Unit

E-bulletin Library and Documentation Unit ………. Honor the past and create the future INSIDE THE ISSUE INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION This e-bulletin gives an overview of the work done by CEHAT on the charita- ble hospitals in Mumbai with a summary of Research and Advocacy. STATE AIDED CHARITABLE CEHAT has been actively involved in issues such as Health Financing, Regu- HOSPITALS IN MUMBAI lation of Private Healthcare Sector, Gender & Health and Violence against OBJECTIVES OF women. One of the areas of research in past year was the state aided charitable THE STUDY KEY FINDINGS hospitals. Visit the website ADVOCACY LIST OF THE CHARITABLE HOSPITALS STATE AIDED CHARITABLE HOSPITALS IN CEHAT RESOURCES MUMBAI PUBLICATION CATALOGUE Charitable Trust Hospitals get various benefits from the government such as HIGHLIGHT LI- land, electricity at subsidized rates, concessions on import duty and income BRARY RE- SOURCES tax, in return for which they are expected to provide free treatment to a certain NEW ARRIVALS number of indigent patients. In 2005, a scheme was instituted by the Mumbai CEHAT IN NEWS High Court formalizing that 20 per cent beds must be set aside for free and concessional treatment at these hospitals. In Mumbai, these hospitals have a UPCOMING PUB- LICATIONS combined capacity of more than 1600 beds. However, it has been brought to ABOUT CEHAT light both by the government and the media that these hospitals routinely flout CONFERENCE their legal obligations. Considering that charitable hospitals are key resources ALERT for provisioning of health services to an already strained public health system, PUBLICATIONS it is vital to ensure their accountability. -

Hotel List 19.03.21.Xlsx

QUARANTINE FACILITIES AVAILABLE AS BELOW (Rate inclusive of Taxes and Three Meals) NO. DISTRICT CATEGORY NAME OF THE HOTEL ADDRESS SINGLE DOUBLE VACANCY POC CONTACT NUMBER FIVE STAR HOTELS 1 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Hilton Andheri (East) 3449 3949 171 Sandesh 9833741347 2 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star ITC Maratha Andheri (East) 3449 3949 70 Udey Schinde 9819515158 3 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Hyatt Regency Andheri (East) 3499 3999 300 Prashant Khanna 9920258787 4 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Waterstones Hotel Andheri (East) 3500 4000 25 Hanosh 9867505283 5 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Renaissance Powai 3600 3600 180 Duty Manager 9930863463 6 Mumbai Surburban 5 Star The Orchid Vile Parle (East) 3699 4250 92 Sunita 9169166789 7 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Sun-N- Sand Juhu, Mumbai 3700 4200 50 Kumar 9930220932 8 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star The Lalit Andheri (East) 3750 4000 156 Vaibhav 9987603147 9 Mumbai Surburban 5 Star The Park Mumbai Juhu Juhu tara Rd. Juhu 3800 4300 26 Rushikesh Kakad 8976352959 10 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Sofitel Mumbai BKC BKC 3899 4299 256 Nithin 9167391122 11 Mumbai City 5 Star ITC Grand Central Parel 3900 4400 70 Udey Schinde 9819515158 12 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Svenska Design Hotels SAB TV Rd. Andheri West 3999 4499 20 Sandesh More 9167707031 13 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Meluha The Fern Hiranandani Powai 4000 5000 70 Duty Manager 9664413290 14 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Grand Hyatt Santacruz East 4000 4500 120 Sonale 8657443495 15 Mumbai City 5 Star Taj Mahal Palace (Tower) Colaba 4000 4500 81 Shaheen 9769863430 16 Mumbai City 5 Star President, Mumbai Colaba -

MUMBAI RAILWAYS Media Solutions

MUMBAI RAILWAYS Media solutions 1 Quick tag line for railway advertising: Create opportunities to reach out to a wide Positioning variety of audience Various such as families, Reach out to Brands on travelers, students and 7.5 million even children. passengers with our Rail Since moving Billboards 12 Years and promotional activities. 2 Why Railway advertising? Focused exposure at a single point Excellent visibility Wider reach ability to a large spectrum of audience Long and wide distance coverage The large, colorful, innovative designs demand attention. You have exclusivity in your space. 3 How important is Mumbai Railways? Mumbai Suburban Railways operates over 2,300 train services every single day. Mumbai’s local rail network is the busiest commuter train system in the world with 7.5 million people using the trains to commute daily. 4 Commuter details 80% who live in the suburbs, Thane, Palghar districts and Navi Mumbai of the people use local to go from home to office. 80 37 43 10 lakh lakh lakh lakh No of daily No of daily No of daily No of daily commuters commuters commuters commuters on estimated on WR estimated on WR estimated on CR Harbour line and CR 5 Target audience-Central line Masjid Currey Byculla Dadar Sion Vidyavihar Vikhroli Bunder Road Chatrapati Sandhurst Shivaji Chinchpokli Parel Matunga Kurla Ghatkopar Road Terminus Tourist Residential Hospital Commercial Business Religious Students Industrial Shopping Entertainment Corporate People People estates Hub 6 Target audience-Central line Diva Bhandup Mulund Kalwa Dombivli -

Tele Phones : 022-29277177 / 09892473204 / 07208566896 (Whattsapp)

www.saicomponents.com Manufacturers of Testing and Measuring Instruments and Accessories for Electronic Instrumentation Regd. Off. 5A/201, Sunrise, opp. Samna Pariwar, General A. K Vaidya Road, Dindoshi, Malad (East) Mumbai. 400097 Maharashtra, India Tele Phones : 022-29277177 / 09892473204 / 07208566896 (WhattsApp) www.saicomponents.com Manufacturers of Testing and Measuring Instruments and Accessories for Electronic Instrumentation Regd. Off. 5A/201, Sunrise, opp. Samna Pariwar, General A. K Vaidya Road, Dindoshi, Malad (East) Mumbai. 400097 Maharashtra, India Tele Phones : 022-29277177 / 09892473204 / 07208566896 (WhattsApp) www.saicomponents.com Manufacturers of Testing and Measuring Instruments and Accessories for Electronic Instrumentation Regd. Off. 5A/201, Sunrise, opp. Samna Pariwar, General A. K Vaidya Road, Dindoshi, Malad (East) Mumbai. 400097 Maharashtra, India Patch cord BNC to open type Alligator Clips with RG-59 or RG 58 cable SBC-60 Patch cord BNC to BNC with RG-59 or RG 58 cable SBB-59 Patch cord 4mm rear stackable Banana Plug to open type Alligator clip SPC-4C Patch cord 4mm rear stackable Banana Plug to fully insulated Alligator clip SPC-4CS Tele Phones : 022-29277177 / 09892473204 / 07208566896 (WhattsApp) www.saicomponents.com Manufacturers of Testing and Measuring Instruments and Accessories for Electronic Instrumentation Regd. Off. 5A/201, Sunrise, opp. Samna Pariwar, General A. K Vaidya Road, Dindoshi, Malad (East) Mumbai. 400097 Maharashtra, India Patch cord 4mm rear stackable Banana Plug to 4mm Banana Socket SPC-4S Patch cord Integrally moulded 4mm Side stackable heavy duty Banana Plug on both the end SPC-8 Test Probe 4mm side stackable Banana Plug to 2mm Test Probe STP-10 Test Probe 4mm side stackable Banana Plug to 2mm Test Probe. -

Answered On:31.07.2000 Buildings for Post Offices Baliram

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA COMMUNICATIONS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:1258 ANSWERED ON:31.07.2000 BUILDINGS FOR POST OFFICES BALIRAM Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state: (a) the details of post offices functioning in rented buildings particularly in Azamgarh and Mau districts of U.P. and Mumbai in Maharashtra, district-wise; (b) the amount paid by the Government as rent for these buildings during 1999-2000; (c) whether the Government propose to construct departmental buildings for the post offices at those places; (d) if so, the details thereof, district-wise; and (e) if not, the reasons therefor? Answer MINISTER OF STATE FOR COMMUNICATIONS (SHRI TAPAN SIKDAR): (a) There are a total of 2599 post offices functioning in rented buildings in U.P. and 228 post offices functioning in rented buildings in Mumbai city. Details of the post offices functioning in rented buildings particularly in Azamgarh and Mau district of U.P. and Mumbai in Maharashtra is given district wise at Annexure `A`. (b) The amount paid by the Government as rent for these rented buildings is given at Annexure `B`. (c) There is no immediate proposal for construction of departmental buildings at place mentioned in (a) above. (d)&(e) No reply called for in view of (c) above. STATEMENT IN RESPECT OF PART (a) & (b) OF THE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 1258 FOR 31ST JULY, 2000 REGARDING BUILDINGS FOR POST OFFICES. ANNEXURE `A` (a) The details of post offices functioning in Azamgarh districts, district wise is as follows: Ahraula, Ambari, Atraulia, Azamgarh -

India Architecture Guide 2017

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Zone 1: Zanskar Geologically, the Zanskar Range is part of the Tethys Himalaya, an approximately 100-km-wide synclinorium. Buddhism regained its influence Lungnak Valley over Zanskar in the 8th century when Tibet was also converted to this ***** Zanskar Desert ཟངས་དཀར་ religion. Between the 10th and 11th centuries, two Royal Houses were founded in Zanskar, and the monasteries of Karsha and Phugtal were built. Don't miss the Phugtal Monastery in south-east Zanskar. Zone 2: Punjab Built in 1577 as the holiest Gurdwara of Sikhism. The fifth Sikh Guru, Golden Temple Rd, Guru Arjan, designed the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) to be built in Atta Mandi, Katra the centre of this holy tank. The construction of Harmandir Sahib was intended to build a place of worship for men and women from all walks *** Golden Temple Guru Ram Das Ahluwalia, Amritsar, Punjab 143006, India of life and all religions to come and worship God equally. The four entrances (representing the four directions) to get into the Harmandir ਹਰਿਮੰਦਿ ਸਾਰਹਬ Sahib also symbolise the openness of the Sikhs towards all people and religions. Mon-Sun (3-22) Near Qila Built in 2011 as a museum of Sikhism, a monotheistic religion originated Anandgarh Sahib, in the Punjab region. Sikhism emphasizes simran (meditation on the Sri Dasmesh words of the Guru Granth Sahib), that can be expressed musically *** Virasat-e-Khalsa Moshe Safdie Academy Road through kirtan or internally through Nam Japo (repeat God's name) as ਰਿਿਾਸਤ-ਏ-ਖਾਲਸਾ a means to feel God's presence.