New Approaches and Old Mechanisms for Combatting Impunity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

En En Mission Report

European Parliament 2014-2019 Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs 14.11.2018 MISSION REPORT following the Ad - hoc delegation to Slovakia and Malta 17-20 September 2018 Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs Members of the mission: Sophia in 't Veld (ALDE) (Leader of the mission) Roberta Metsola (PPE) Josef Weidenholzer (S&D) Monica Macovei (ECR) Sven Giegold (Verts/ALE) CR\1164444EN.docx PE628.485v01-00 EN United in diversity EN Summary account of meetings The Head of the delegation opened all meetings by recalling the two-fold objective of the ad hoc fact-finding mission, i.e. the investigations on the murders of journalists and the way these are progressing, and on the status of the rule of law and corruption in the two visited countries. Monday, 17 September 2018 12:00 - 13:30 Round table discussions with NGOs active in the fight against corruption Venue: EP Information Office, Palisády 29, SK-811 06 Bratislava The Members of the delegation had an exchange of views with: • Mr Milan Šagát - VIA IURIS - Civil society organisation in the field of justice, rule of law and democracy • Mrs Zuzana Wienk and Peter Kunder - Fair Play Alliance, Civil society organisation in the area of transparency and anti-corruption • Mr Matej Hruška, Bring to a Halt of Corruption – Foundation in the field of fight against corruption. In the exchange the representatives of the NGOs underlined, among others, that: - they would be surprised if the investigations would be closed, underlined that at the beginning they had doubts -

How to Fund Investigative Journalism Insights from the Field and Its Key Donors Imprint

EDITION DW AKADEMIE | 2019 How to fund investigative journalism Insights from the field and its key donors Imprint PUBLISHER RESPONSIBLE PUBLISHED Deutsche Welle Jan Lublinski September 2019 53110 Bonn Carsten von Nahmen Germany © DW Akademie EDITORS AUTHOR Petra Aldenrath Sameer Padania Nadine Jurrat How to fund investigative journalism Insights from the field and its key donors Sameer Padania ABOUT THE REPORT About the report This report is designed to give funders a succinct and accessible introduction to the practice of funding investigative journalism around the world, via major contemporary debates, trends and challenges in the field. It is part of a series from DW Akademie looking at practices, challenges and futures of investigative journalism (IJ) around the world. The paper is intended as a stepping stone, or a springboard, for those who know little about investigative journalism, but who would like to know more. It is not a defense, a mapping or a history of the field, either globally or regionally; nor is it a description of or guide to how to conduct investigations or an examination of investigative techniques. These are widely available in other areas and (to some extent) in other languages already. Rooted in 17 in-depth expert interviews and wide-ranging desk research, this report sets out big-picture challenges and oppor- tunities facing the IJ field both in general, and in specific regions of the world. It provides donors with an overview of the main ways this often precarious field is financed in newsrooms and units large and small. Finally it provides high-level practical ad- vice — from experienced donors and the IJ field — to help new, prospective or curious donors to the field to find out how to get started, and what is important to do, and not to do. -

IMPACT REPORT a Word from the Founder and Director|

2017 - 2020 IMPACT REPORT A word from the founder and director| In October 2017 as we were preparing to launch a collaborative " network of journalists dedicated to pursuing and publishing the work of other reporters facing threats, prison or murder, prominent Maltese investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was horrifically silenced with a car bomb. Her murder was a cruel and stark reminder of how tenuous the free flow of information can be when democratic systems falter. We added Daphne to the sad and long list of journalists whose work Forbidden Stories is committed to continuing. For five months, we coordinated a historic collaboration of 45 journalists from 18 news organizations, aimed at keeping Daphne Caruana Galizia’s stories alive. Her investigations, as a result of this, ended up on the front pages of the world’s most widely-read newspapers. Seventy-four million people heard about the Daphne Project worldwide. Although her killers had hoped to silence her stories, the stories ended up having an echo way further than Malta. LAURENT RICHARD Forbidden Stories' founder Three years later, the journalists of the Daphne Project continue and executive director. to publish new revelations about her murder and pursue the investigations she started. Their explosive role in taking down former Maltese high-ranking government officials confirms that collaboration is the best protection against impunity. 2 2017-2020 Forbidden Stories Impact Report A word from the founder and director| That’s why other broad collaborative On a smaller scale, we have investigations followed. developed rapid response projects. We investigated the circumstances The Green Blood Project, in 2019, pursued behind the murders of Ecuadorian, the stories of reporters in danger for Mexican and Ghanaian journalists; investigating environmental scandals. -

Stephen Grey – Draft of Opening Remarks – Check Vs Delivery 1

STEPHEN GREY – DRAFT OF OPENING REMARKS – CHECK VS DELIVERY 1 Ladies and Gentleman, I am honored to be invited to speak to the European Parliament, though saddened that – due to my government’s intentions – I may not be able to return again as a European citizen. I have been a journalist for 30 years, today working as a special correspondent at the Reuters news agency in its investigative team that produces in depth articles on matters of public interest. I am not here however to represent Reuters but the Daphne Project, which I helped to found under the leadership and coordination of Forbidden Stories, an NGO based in Paris, which continues the work of slain or imprisoned journalists. Any opinions I may express, however, are my own. It is on facts, however, that I wish to assist on. I have reported on Malta and the legacy of Daphne Caruana Galizia objectively and without partisan concern. I will address our specific factual conclusions. But first some general points. The object of journalism is not to prove a crime; just as it is not the job of politicians in a healthy democracy to send their opponents to jail. We are both – journalists and parliamentarians – detectives of last resort, aiming to shed public light on the facts of an injustice or wrongdoing when the specialist agencies of government – police, magistrates or public regulators are failing. We do not have powers of subpoena or arrest, so we cannot replace official inquiries: we can only hold them to account. STEPHEN GREY – DRAFT OF OPENING REMARKS – CHECK VS DELIVERY 2 Daphne made a number of allegations about wrongdoing in Malta. -

European Parliament Resolution of 28 March 2019 on The

26.3.2021 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 108/107 Thursday 28 March 2019 P8_TA(2019)0328 Situation of rule of law and fight against corruption in the EU, specifically in Malta and Slovakia European Parliament resolution of 28 March 2019 on the situation of the rule of law and the fight against corruption in the EU, specifically in Malta and Slovakia (2018/2965(RSP)) (2021/C 108/10) The European Parliament, — having regard to Articles 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 and 10 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), — having regard to Article 20 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), — having regard to Articles 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12 and 47 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, — having regard to the opinion on questions relating to the appointment of judges of the constitutional court of the Slovak Republic, adopted by the Venice Commission at its 110th Plenary Session (Venice, 10-11 March 2017), — having regard to the opinion on constitutional arrangements and separation of powers and the independence of the judiciary and law enforcement in Malta, adopted by the Venice Commission at its 117th Plenary Session (Venice, 14-15 December 2018), — having regard to the report of 23 January 2019 from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions entitled ‘Investor Citizenship and Residence Schemes in the European Union’ (COM(2019)0012), — having regard to its resolution of 16 January 2014 on EU citizenship for sale (1) and to -

European Commission Berlaymont Rue De La Loi 200, 1049 Brussels Brussels, 10 October 2018 First Vice-President Timmermans, Commissioner Jourová

European Commission Berlaymont Rue de la Loi 200, 1049 Brussels Brussels, 10 October 2018 First Vice-President Timmermans, Commissioner Jourová, In view of the latest revelations of the Daphne Project, a group of world-renowned journalists continuing the work of investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, we feel it is our duty to draw your attention to the following facts relevant to the investigation into the assassination of Daphne Caruna Galizia: Politicians exposed by Daphne Caruana Galizia’s reporting to be involved in corruption and money laundering continue to hold public office. Keith Schembri, the Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff and Konrad Mizzi, the Tourism minister, were exposed by the Panama Papers leak as the UBOs of offshore companies into which they planned to funnel exorbitant funds that could not be legitimately explained; 1 Ali Sadr Hasheminejad, the owner of Pilatus Bank, exposed by Daphne Caruana Galizia’s reporting as being involved in money laundering for PEPs including Keith Schembri and the Azeri regime, is now facing a 125-year prison sentence in the United States.2 The request to withdraw Pilatus Bank’s license was only made after the arrest of Mr Hasheminejad;3 Nexia BT, the firm that represented Mossack Fonseca in Malta and worked in concert with Mossack Fonseca to create the money laundering structures exposed by Daphne Caruana Galizia’s reporting, continues to operate without consequence and continues to receive lucrative government contracts;4 Silvio Valletta, the Assistant Commissioner of Police, led the investigation into the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia. He is the husband of a government minister who was also criticised by Daphne Caruana Galizia. -

Daphne Caruana Galizia's Assassination and The

Restricted AS/Jur (2019) 23 20 May 2019 ajdoc23 2019 Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights Daphne Caruana Galizia’s assassination and the rule of law, in Malta and beyond: ensuring that the whole truth emerges Draft report Rapporteur: Mr Pieter OMTZIGT, the Netherlands, Group of the European People’s Party A. Preliminary draft resolution 1. Daphne Caruana Galizia, Malta’s best known and most widely-read investigative journalist, whose work focused on corruption amongst Maltese politicians and public officials, was assassinated by a car bomb close to her home on 16 October 2017. The response of the international community was immediate. Within the Council of Europe, the President of the Parliamentary Assembly, the Secretary General and the Commissioner for Human Rights all called for a thorough investigation of the murder. Ms Caruana Galizia’s murder and the continuing failure of the Maltese authorities to bring the suspected killers to trial or identify those who ordered her assassination raise serious questions about the rule of law in Malta. 2. Recalling the recent conclusions of the European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission) and the Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) concerning Malta, the Assembly notes the following: 2.1. The Prime Minister of Malta is predominant in Malta’s constitutional arrangements, sitting at the centre of political power, with extensive powers of appointment; 2.2. The Office of the Prime Minister has taken over responsibility for various areas of activity that present particular risks of money laundering, including on-line gaming, investment migration (‘golden passports’) and regulation of financial services, including cryptocurrencies; 2.3. -

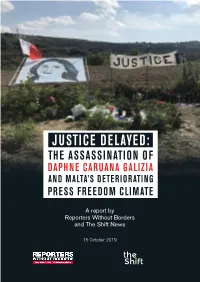

A Report by Reporters Without Borders and the Shift News

A report by Reporters Without Borders and The Shift News 15 October 2019 CONTENTSI Acknowledgements 2 Executive Summary 3 1 - Chapter One: An unthinkable act 4 2 - Chapter Two: Investigating the assassination 7 3 - Chapter Three: The magisterial inquiry and police interference 20 4 - Chapter Four: Malta’s deteriorating press freedom climate 25 5 - Chapter Five: The international reaction 35 6 - Chapter Six: An urgent need for an independent and impartial public inquiry 42 Concluding observations and recommendations 46 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This publication is a joint report of Reporters Without Borders (RSF) and The Shift News, researched and co-authored by RSF UK Bureau Director Rebecca Vincent and The Shift News Founder and Editor Caroline Muscat. Editorial support was provided by RSF Editor-in-Chief Bertin Leblanc and the Head of RSF’s EU-Balkans Desk, Pauline Adès-Mével, with proofreading done by RSF UK Programme Assistant Katie Fallon. This report has been published with the kind financial support of the Justice for Journalists Foundation. 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARYN On 16 October 2017, journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was assassinated by a car bomb that detonated near her home in Bidnija, Malta – an act that was previously unthinkable in an EU state. Caruana Galizia was the country’s most prominent journalist, known for her courageous investigative reporting exposing official corruption in Malta and beyond, including her reporting on the Panama Papers. A full two years on, there has still been no justice for this heinous assassination, which has shed light on broader systemic failings with regard to Malta’s press freedom climate, rule of law, and democratic checks and balances. -

1 Combating Impunity for Killings of Journalists

COMBATING IMPUNITY FOR KILLINGS OF JOURNALISTS Lessons to be learned from murders of Daphne Caruana Galizia and Jan Kuciak by Šejla Karić LLM Human Rights Capstone Thesis SUPERVISORS: Professor Miklós Haraszti Professor Sejal Parmar Central European University CEU eTD Collection © Central European University 7 June 2020 1 Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................3 Chapter 1: Indicating the problem ........................................................................................................5 Chapter 2: Outlining the legal obligations.............................................................................................9 Chapter 3: Malta and Slovakia’s responses to murders of journalists .................................................... 11 3.1. Case study 1: Murder of Daphne Caruana Galizia in Malta........................................................ 11 3.2. Case study 2: Murder of Jan Kuciak in Slovakia ....................................................................... 12 3.3. Malta’s response to the murder of Daphne Caruana Galizia ....................................................... 13 3.4. Slovakia’s response to the murder of Jan Kuciak ...................................................................... 16 Chapter 4: Comparative analysis of the factors that influenced state responses ...................................... 18 4.1. Journalist community movements ........................................................................................... -

IMPACT REPORT a Word from the Founder and Director|

2017 - 2020 IMPACT REPORT A word from the founder and director| In October 2017 as we were preparing to launch a collaborative " network of journalists dedicated to pursuing and publishing the work of other reporters facing threats, prison or murder, prominent Maltese investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was horrifically silenced with a car bomb. Her murder was a cruel and stark reminder of how tenuous the free flow of information can be when democratic systems falter. We added Daphne to the sad and long list of journalists whose work Forbidden Stories is committed to continuing. For five months, we coordinated a historic collaboration of 45 journalists from 18 news organizations, aimed at keeping Daphne Caruana Galizia’s stories alive. Her investigations, as a result of this, ended up on the front pages of the world’s most widely-read newspapers. Seventy-four million people heard about the Daphne Project worldwide. Although her killers had hoped to silence her stories, the stories ended up having an echo way further than Malta. LAURENT RICHARD Forbidden Stories' founder Three years later, the journalists of the Daphne Project continue and executive director. to publish new revelations about her murder and pursue the investigations she started. Their explosive role in taking down former Maltese high-ranking government officials confirms that collaboration is the best protection against impunity. 2 2017-2020 Forbidden Stories Impact Report A word from the founder and director| That’s why other broad collaborative On a smaller scale, we have investigations followed. developed rapid response projects. We investigated the circumstances The Green Blood Project, in 2019, pursued behind the murders of Ecuadorian, the stories of reporters in danger for Mexican and Ghanaian journalists; investigating environmental scandals. -

Rebuilding Investigative Journalism. Collaborative Journalism: Sharing Information, Sharing Risk

Observatorio (OBS*) Journal, (2020, vol14, no4), 135-157 1646-5954/ERC123483/2020 135 Rebuilding investigative journalism. Collaborative journalism: sharing information, sharing risk Pedro Coelho*, Inês Alves Rodrigues* *Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal Abstract This article details the role of collaborative journalism during the process of rebuilding investigative journalism at its core thus assuring enduring investment in its quality. We will start by characterizing the concepts of investigative journalism and collaborative journalism, using leading scholars in both of these complementary areas; we will, then, identify the pressures that constrains investigative journalism, and analyse how journalistic collaboration has a potential for resistance that can protect both investigative journalism and the journalists who practice it. Our article path will be complemented with the case study of the “Daphne Project”, the first project of the consortium “Forbidden Stories”, the international platform created by Laurent Richard. This project will be characterized through a documentary analysis and with interviews we conducted with both its founder, Laurent Richard, and Mathew Caruana Galizia, the son of Daphne Caruana Galizia, the Maltese journalist murdered on October 16th 2017, during her investigations. The Daphne Project was created for the purpose of keeping alive stories of journalists who have been killed, imprisoned or, for some reason, were unable to pursue their investigations. Not only does collaborative journalism protect investigative journalism and investigative journalists, but cross-borders collaboration also allows “sharing the risk across a wide range of international players” (Sambrook, 2017). If the absolute exposure of the lonely investigative journalist turns him/her into a target in territories where freedom of speech is threatened, the murder of this Maltese journalist, followed by the murder of Slovakian Ján Kuciak, in 2018, placed Europe as an unlikely set on the risk map. -

Letter Fius David Casa.Pdf

Financial Intelligence Unit For the attention of the Director 26 April 2018 Dear Director, I wish to bring to your attention evidence of systemic money laundering by Pilatus Bank - an entity operating with a Maltese license and based in Malta. Pilatus Bank’s clients are predominantly Azeri politically exposed persons. In addition, the bank has been shown to launder money derived from corruption for top Maltese government officials. The bank’s AML violation have been described as ‘glaring’ and ‘deliberate’ in documents leaked from Malta’s anti-money laundering agency (the ‘FIAU’). Pilatus Bank applied for a banking licence with the Malta Financial Services Authority in December 2013. The licence was issued less than one month later, on 2 January 2014. A few months after the licence was issued, in May 2014, the United States Treasury Department issued a FinCEN advisory FIN-2014- A004. The notice alerted financial institutions worldwide to a pattern of Iranian nationals purchasing St Kitts & Nevis passports ‘in order to facilitate financial crime’. The owner of Pilatus Bank, Seyed Ali Sadr Hasheminejad, is an Iranian national who purchased a St Kitts & Nevis passport through Henley & Partners in 2009. The CEO of the bank, Hamidreza Ghanbari, is an Iranian national with a Dominican passport. The mother company of Pilatus Bank in Malta is Pilatus Capital Ltd, a UK company opened in 2008 by Mehdi Shamszadeh (a.k.a. Shams), an Iranian national who acquired British citizenship in 2011. Shamszadeh was sentenced to death in Iran following a conviction on charges of embezzlement of billions of dollars of public revenue while he was a director of the Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Line, and while tasked with circumventing sanctions for his country’s Ministry of Oil.