Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

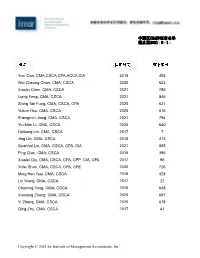

中国区cma持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日

中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Yixu Cao, CMA,CSCA,CPA,ACCA,CIA 2019 492 Wai Cheung Chan, CMA, CSCA 2020 622 Xiaolin Chen, CMA, CSCA 2021 785 Liang Feng, CMA, CSCA 2021 845 Shing Tak Fung, CMA, CSCA, CPA 2020 621 Yukun Hsu, CMA, CSCA 2020 676 Shengmin Jiang, CMA, CSCA 2021 794 Yiu Man Li, CMA, CSCA 2020 640 Huikang Lin, CMA, CSCA 2017 7 Jing Lin, CMA, CSCA 2018 415 Quanhui Liu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CIA 2021 855 Ping Qian, CMA, CSCA 2018 396 Xiaolei Qiu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFP, CIA, CFA 2017 96 Yufei Shan, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFE 2020 726 Ming Han Tsai, CMA, CSCA 2018 428 Lin Wang, CMA, CSCA 2017 22 Chunling Yang, CMA, CSCA 2020 648 Xiaolong Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 697 Yi Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 678 Qing Zhu, CMA, CSCA 2017 41 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. 中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Siha A, CMA 2020 81134 Bei Ai, CMA 2020 84918 Danlu Ai, CMA 2021 94445 Fengting Ai, CMA 2019 75078 Huaqin Ai, CMA 2019 67498 Jie Ai, CMA 2021 94013 Jinmei Ai, CMA 2020 79690 Qingqing Ai, CMA 2019 67514 Weiran Ai, CMA 2021 99010 Xia Ai, CMA 2021 97218 Xiaowei Ai, CMA, CIA 2019 75739 Yizhan Ai, CMA 2021 92785 Zi Ai, CMA 2021 93990 Guanfei An, CMA 2021 99952 Haifeng An, CMA 2021 92781 Haixia An, CMA 2016 51078 Haiying An, CMA 2021 98016 Jie An, CMA 2012 38197 Jujie An, CMA 2018 58081 Jun An, CMA 2019 70068 Juntong An, CMA 2021 94474 Kewei An, CMA 2021 93137 Lanying An, CMA, CPA 2021 90699 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. -

![Directors, Supervisors and Parties Involved in the [Redacted]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1262/directors-supervisors-and-parties-involved-in-the-redacted-21262.webp)

Directors, Supervisors and Parties Involved in the [Redacted]

THIS DOCUMENT IS IN DRAFT FORM. THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN IS INCOMPLETE AND IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE. THIS DOCUMENT MUST BE READ IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE SECTION HEADED “WARNING” ON THE COVER OF THIS DOCUMENT. DIRECTORS, SUPERVISORS AND PARTIES INVOLVED IN THE [REDACTED] DIRECTORS AND SUPERVISORS Name Address Nationality Executive Directors Mr. Sun Haijin Room 211, Building 1 Chinese Airport Sidao Air Cargo Terminal, Baoan District, Shenzhen Mr. Tsang Hoi Lam Flat C, 15/F, Block 1 Chinese Greenfield Garden (Hong Kong) NO 2-20, Palm Street, Tai Kok Tsui Hong Kong Mr. Chen Lin Room 702, Block 1, Building 17 Chinese Fangrunxuan Huaming Street, Hongze Revenue Dongli District Tianjin Non-executive Directors Mr. Chan Fei Room 32A, Block 2 Chinese Harbour Green (Hong Kong) NO. 8, Sham Mong Road Tai Kok Tsui Yau Tsim Mong District Hong Kong Mr. Xu Zhijun Room 6B, Building 29 Chinese Cuihua Garden Huali Road Luohuo District Shenzhen Mr. Li Qiuyu 28th Floor Chinese No. 90, Zhongshan East Road Qinhuai District Nanjing Jiangsu Province –72– THIS DOCUMENT IS IN DRAFT FORM. THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN IS INCOMPLETE AND IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE. THIS DOCUMENT MUST BE READ IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE SECTION HEADED “WARNING” ON THE COVER OF THIS DOCUMENT. DIRECTORS, SUPERVISORS AND PARTIES INVOLVED IN THE [REDACTED] Independent non-executive Directors Mr. Chan Kok Chung No.70, Cedar Drive Chinese Redhill Peninsula (Hong Kong) Tai Tam Hong Kong Mr. Wong Hak Kun 13th Floor, Block A1 Chinese Nicholson Tower (Hong Kong) No. 8, Wong Nai Chung Gap Road Hong Kong Mr. Zhou Xiang Room 21A, Block 3 Chinese The Hermitage, Mong Kok, Kowloon (Hong Kong) Hong Kong Supervisors Mr. -

The South China Sea and Its Coral Reefs During the Ming and Qing Dynasties: Levels of Geographical Knowledge and Political Control Ulisesgrana Dos

East Asian History NUMBER 32/33 . DECEMBER 20061]uNE 2007 Institute of Advanced Studies The Australian National University Editor Benjamin Penny Associate Editor Lindy Shultz Editorial Board B0rge Bakken Geremie R. Barme John Clark Helen Dunstan Louise Edwards Mark Elvin Colin Jeffcott Li Tana Kam Louie Lewis Mayo Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Kenneth Wells Design and Production Oanh Collins Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This is a double issue of East Asian History, 32 and 33, printed in November 2008. It continues the series previously entitled Papers on Far Eastern History. This externally refereed journal is published twice per year. Contributions to The Editor, East Asian History Division of Pacific and Asian History Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Phone +61 2 6125 5098 Fax +61 2 6125 5525 Email [email protected] Subscription Enquiries to East Asian History, at the above address Website http://rspas.anu.edu.au/eah/ Annual Subscription Australia A$50 (including GST) Overseas US$45 (GST free) (for two issues) ISSN 1036-6008 � CONTENTS 1 The Moral Status of the Book: Huang Zongxi in the Private Libraries of Late Imperial China Dunca n M. Ca mpbell 25 Mujaku Dochu (1653-1744) and Seventeenth-Century Chinese Buddhist Scholarship John Jorgensen 57 Chinese Contexts, Korean Realities: The Politics of Literary Genre in Late Choson Korea (1725-1863) GregoryN. Evon 83 Portrait of a Tokugawa Outcaste Community Timothy D. Amos 109 -

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory Pictures in a Time of Defeat: Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory pictures in a time of defeat: depicting war in the print and visual culture of late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/18449 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. VICTORY PICTURES IN A TIME OF DEFEAT Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884-1901 Yin Hwang Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the History of Art 2014 Department of the History of Art and Archaeology School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 2 Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. -

Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: the Great Qing and the Maritime World

Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: The Great Qing and the Maritime World in the Long Eighteenth Century Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultüt der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt von Chung-yam PO Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Harald Fuess Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Joachim Kurtz Datum: 28 June 2013 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Acknowledgments 3 Emperors of the Qing Dynasty 5 Map of China Coast 6 Introduction 7 Chapter 1 Setting the Scene 43 Chapter 2 Modeling the Sea Space 62 Chapter 3 The Dragon Navy 109 Chapter 4 Maritime Customs Office 160 Chapter 5 Writing the Waves 210 Conclusion 247 Glossary 255 Bibliography 257 1 Abstract Most previous scholarship has asserted that the Qing Empire neglected the sea and underestimated the worldwide rise of Western powers in the long eighteenth century. By the time the British crushed the Chinese navy in the so-called Opium Wars, the country and its government were in a state of shock and incapable of quickly catching-up with Western Europe. In contrast with such a narrative, this dissertation shows that the Great Qing was in fact far more aware of global trends than has been commonly assumed. Against the backdrop of the long eighteenth century, the author explores the fundamental historical notions of the Chinese maritime world as a conceptual divide between an inner and an outer sea, whereby administrators, merchants, and intellectuals paid close and intense attention to coastal seawaters. Drawing on archival sources from China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and the West, the author argues that the connection between the Great Qing and the maritime world was complex and sophisticated. -

Daoist Symbols of Immortality and Longevity : on Late Ming Dynasty Porcelain

Daoist symbols of immortality and longevity : on late Ming Dynasty porcelain Autor(en): Vries, Patrick de Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Asiatische Studien : Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Asiengesellschaft = Études asiatiques : revue de la Société Suisse-Asie Band (Jahr): 62 (2008) Heft 1 PDF erstellt am: 11.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-147774 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch DAOIST SYMBOLS OF IMMORTALITY AND LONGEVITY ON LATE MING DYNASTY PORCELAIN Patrick de Vries, Zurich Abstract This paper explores aspects of Daoist symbolism as found on the ceramics produced during the Jiajing (˜iå reign 1522– 1566) of the late Ming dynasty. -

Adaptive Fuzzy Pid Controller's Application in Constant Pressure Water Supply System

2010 2nd International Conference on Information Science and Engineering (ICISE 2010) Hangzhou, China 4-6 December 2010 Pages 1-774 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1076H-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-7616-9 1 / 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS ADAPTIVE FUZZY PID CONTROLLER'S APPLICATION IN CONSTANT PRESSURE WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM..............................................................................................................................................................................................................1 Xiao Zhi-Huai, Cao Yu ZengBing APPLICATION OF OPC INTERFACE TECHNOLOGY IN SHEARER REMOTE MONITORING SYSTEM ...............................5 Ke Niu, Zhongbin Wang, Jun Liu, Wenchuan Zhu PASSIVITY-BASED CONTROL STRATEGIES OF DOUBLY FED INDUCTION WIND POWER GENERATOR SYSTEMS.................................................................................................................................................................................9 Qian Ping, Xu Bing EXECUTIVE CONTROL OF MULTI-CHANNEL OPERATION IN SEISMIC DATA PROCESSING SYSTEM..........................14 Li Tao, Hu Guangmin, Zhao Taiyin, Li Lei URBAN VEGETATION COVERAGE INFORMATION EXTRACTION BASED ON IMPROVED LINEAR SPECTRAL MIXTURE MODE.....................................................................................................................................................................18 GUO Zhi-qiang, PENG Dao-li, WU Jian, GUO Zhi-qiang ECOLOGICAL RISKS ASSESSMENTS OF HEAVY METAL CONTAMINATIONS IN THE YANCHENG RED-CROWN CRANE NATIONAL NATURE RESERVE BY SUPPORT -

Ming China As a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Winter 12-15-2018 Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Duan, Weicong, "Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620" (2018). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1719. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1719 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Dissertation Examination Committee: Steven B. Miles, Chair Christine Johnson Peter Kastor Zhao Ma Hayrettin Yücesoy Ming China as a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 by Weicong Duan A dissertation presented to The Graduate School of of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 St. Louis, Missouri © 2018, -

Violence and Predation, Mainly in the Form of Piracy, Were Two Of

violence and predation robert j. antony Violence and Predation on the Sino-Vietnamese Maritime Frontier, 1450–1850 iolence and predation, mainly in the form of piracy, were two of V the most persistent and pervasive features of the Sino-Vietnamese maritime frontier between the mid-fifteenth and mid-nineteenth cen- turies.1 In the Gulf of Tonkin, which is the focus of this article, piracy was, in fact, an intrinsic feature of this sea frontier and a dynamic and significant force in the region’s economic, social, and cultural devel- opment. My approach, what scholars call history from the bottom up, places pirates, not the state, at center stage, recognizing their impor- tance and agency as historical actors. My research is based on various types of written history, including Qing archives, the Veritable Records of Vietnam and China, local Chinese gazetteers, and travel accounts; I also bring in my own fieldwork in the gulf region conducted over the past six years. The article is divided into three sections: first, I discuss the geopolitical characteristics of this maritime frontier as a background to our understanding of piracy in the region; second, I consider the socio-cultural aspects of the gulf region, especially the underclass who engaged in clandestine activities as a part of their daily lives; and third, I analyze five specific episodes of piracy in the Gulf of Tonkin. The Gulf of Tonkin (often referred to here simply as the gulf), which is tucked away in the northwestern corner of the South China Sea, borders on Vietnam in the west and China in the north and east. -

P020110307527551165137.Pdf

CONTENT 1.MESSAGE FROM DIRECTOR …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 03 2.ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 05 3.HIGHLIGHTS OF ACHIEVEMENTS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 Coexistence of Conserve and Research----“The Germplasm Bank of Wild Species ” services biodiversity protection and socio-economic development ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 The Structure, Activity and New Drug Pre-Clinical Research of Monoterpene Indole Alkaloids ………………………………………… 09 Anti-Cancer Constituents in the Herb Medicine-Shengma (Cimicifuga L) ……………………………………………………………………………… 10 Floristic Study on the Seed Plants of Yaoshan Mountain in Northeast Yunnan …………………………………………………………………… 11 Higher Fungi Resources and Chemical Composition in Alpine and Sub-alpine Regions in Southwest China ……………………… 12 Research Progress on Natural Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV) Inhibitors…………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Predicting Global Change through Reconstruction Research of Paleoclimate………………………………………………………………………… 14 Chemical Composition of a traditional Chinese medicine-Swertia mileensis……………………………………………………………………………… 15 Mountain Ecosystem Research has Made New Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Plant Cyclic Peptide has Made Important Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Progresses in Computational Chemistry Research ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 New Progress in the Total Synthesis of Natural Products ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… -

Eight Transitional Treasures Eight Transitional Treasures 30Th Anniversary Exhibition

Eight Transitional Treasures Eight Transitional Treasures 30th Anniversary Exhibition BERWALD ORIENTAL ART LONDON 2 Introduction [Chinese] Chronology of This exhibition encompasses a ffty-year period that saw the 本展涵蓋明末清初半世紀,見證明代衰亡,滿清立國。自 emperors decline and eventual fall of the Ming dynasty and ended with the 約1620年起至1670年代中期間,中華製瓷工藝之風格及題 Ming dynasty establishment of the new Manchurian Qing dynasty. Lasting roughly Jiajing from 1620 to the mid 1670s, this period marks a remarkable change 材經歷嬗變,非比尋常。雖時局動盪,然官窰並無衰落之 1521 – 1567 in the style and subject matter of Chinese porcelain manufacture. Far Wanli 象,反而推陳翻新,臻藝菁華。明朝宮廷燒製大批瓷器, from suffering a decline during this turbulent time, the imperial kilns 1572 – 1620 壟斷生產,至明末衰落,無力繼承奢風,瓷器工藝改為富 Tianqi experienced a period of astounding creativity and artistic brilliance. 1621 – 1627 The Ming court, whose massive orders had until now totally domi- 商巨賈而製。後者鍾情山水景物,熱衷瓷器鑑賞,成就製 Chongzhen nated porcelain production, could no longer sustain their customary 1628 – 1644 瓷技術創新突破,於中華史上獨一無二。 extravagance and a new clientele of wealthy merchants took their Qing dynasty place. It was the tastes and aspirations of this new clientele, particu- 自宋(西元960 - 1279年)前起,製瓷均乃中國之重要工 Shunzhi larly their love of landscapes, which prompted this period of breath- 1644 – 1661 業,至晚明為極盛。宮廷需求熱切,御窰廠供不應求,故 Kangxi taking innovation in porcelain making, which remains unique in 1662 – 1722 Chinese history. 寄燒於規模較小之民窰,有謂「官搭民燒」。江西景德鎮 Porcelain had been a major industry in China since before the 御窰製作規模龐大,架構精密,除瓷匠與畫師外,司爐、 Song dynasty (960 - 1279) and in the late Ming production was at its 木匠、木材商人、礦工、陶土加工師等從業者眾,或直接 height. Court orders were so numerous that the imperial kilns had to farm out orders to smaller private kilns, a practice that became 受聘,或從中得利,經營、運輸等人數極多,更不在話下。 known as ‘ordered by the government, fred by the people’. -

Catholic Music in Macau and Mainland China During the Late Ming and Early Qing Dynasties

224 Chapter 7 Chapter 7 Catholic Music in Macau and Mainland China during the Late Ming and Early Qing Dynasties In this essay, the expression “Catholic music” is used to refer to the European music brought to Macau and mainland China directly by European missionar- ies, including musical theory, musical composition, musical instruments, and the chants used in Catholic ritual.1 Before the Ming dynasty (i.e., prior to 1368), many Christian churches had been built in China thanks to the spread of Christianity during the Tang (618–907), Song (960–1279), and Yuan (1279–1368) dynasties. During the Yuan dynasty, for example, Franciscan missionaries built three magnificent churches in Quanzhou city alone.2 It can be assumed, therefore, that Catholic music would have been introduced into China together with church music well before the Yuan dynasty. However, after the Yuan dynasty, as Catholicism disappeared in China, Catholic music also vanished. As European merchants and missionaries headed east from the middle years of the Ming dynasty onwards, Catholic music was once again introduced into China. According to the available sources, Shuangyu port, in the Ningbo area of Zhejiang province, was the first place into which Catholic music was introduced during the Ming period. The Portuguese explorer Fernão Mendes Pinto 平托 (1509–83) gave the following account of Shuangyu port: Antonio de Faria boarded this boat. Amid the extremely loud music of trumpet, flute, timpani, treble flute, and bass drum as well as the earsplit- 1 The research on this topic