Boundary Spanning and Intermediation for Urban Regeneration: Comparative Case Studies from Three Indian Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thiruvallur District

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR 2017 TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT tmt.E.sundaravalli, I.A.S., DISTRICT COLLECTOR TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT TAMIL NADU 2 COLLECTORATE, TIRUVALLUR 3 tiruvallur district 4 DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT - 2017 INDEX Sl. DETAILS No PAGE NO. 1 List of abbreviations present in the plan 5-6 2 Introduction 7-13 3 District Profile 14-21 4 Disaster Management Goals (2017-2030) 22-28 Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability analysis with sample maps & link to 5 29-68 all vulnerable maps 6 Institutional Machanism 69-74 7 Preparedness 75-78 Prevention & Mitigation Plan (2015-2030) 8 (What Major & Minor Disaster will be addressed through mitigation 79-108 measures) Response Plan - Including Incident Response System (Covering 9 109-112 Rescue, Evacuation and Relief) 10 Recovery and Reconstruction Plan 113-124 11 Mainstreaming of Disaster Management in Developmental Plans 125-147 12 Community & other Stakeholder participation 148-156 Linkages / Co-oridnation with other agencies for Disaster 13 157-165 Management 14 Budget and Other Financial allocation - Outlays of major schemes 166-169 15 Monitoring and Evaluation 170-198 Risk Communications Strategies (Telecommunication /VHF/ Media 16 199 / CDRRP etc.,) Important contact Numbers and provision for link to detailed 17 200-267 information 18 Dos and Don’ts during all possible Hazards including Heat Wave 268-278 19 Important G.Os 279-320 20 Linkages with IDRN 321 21 Specific issues on various Vulnerable Groups have been addressed 322-324 22 Mock Drill Schedules 325-336 -

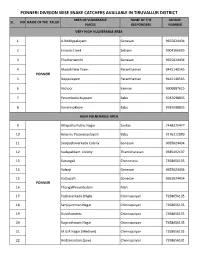

Snake Catchers Available in Tiruvallur District Area of Vulnerable Name of the Mobile Sl

PONNERI DIVISION WISE SNAKE CATCHERS AVAILABLE IN TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT AREA OF VULNERABLE NAME OF THE MOBILE SL. NO NAME OF THE TALUK PLACES RESPONDERS NUMBER VERY HIGH VULNERABLE AREA 1 A.Reddypalayam Ganesan 9655024434 2 Ennore Creek Selvam 9904166695 3 Thathamanchi Ganesan 9655024434 4 Manali New Town Paranthaman 9445140545 PONNERI 5 Nappalayam Paranthaman 9445140545 6 Vichoor Kannan 9600887625 7 Perumbedu Kuppam Babu 9787698835 8 Vanchivakkam Babu 9787698835 HIGH VULNERABLE AREA 9 Athipattu Puthu Nagar Sankar 7448375477 10 Gnayiru Pasavanpalayam Babu 9176212090 11 Sirupazhaverkadu Colony Ganesan 9655024434 12 Kadapakkam Colony Thamizharasan 9585492137 13 Karungali Chinnarasu 7358656135 14 Kalanji Ganesan 9655024434 15 Kattupalli Ganesan 9655024434 PONNERI 16 ThangalPerumbulam Mari 17 Pazhaverkadu (High) Chinnapaiyan 7358656135 18 Senjiyamman Nagar Chinnapaiyan 7358656135 19 Kulathumedu Chinnapaiyan 7358656135 20 Rajarathinam Nagar Chinnapaiyan 7358656135 21 M.G.R Nagar (Medium) Chinnapaiyan 7358656135 22 Andarmadam (Low) Chinnapaiyan 7358656135 PONNERI DIVISION WISE SNAKE CATCHERS AVAILABLE IN TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT AREA OF VULNERABLE NAME OF THE MOBILE SL. NO NAME OF THE TALUK PLACES RESPONDERS NUMBER MEDIUM VULNERABLE AREA Elavur Firka, 23 Ellaiyan & Babu 8754224946 Sunnambukulam Village Gummidipoondi Firka, 24 Ellaiyan & Babu 8754224946 Gummidipoondi EB Village 25 Enathimelpakkam Village Ellaiyan & Babu 8754224946 26 Chinna Soliyambakkam Village Ellaiyan & Babu 8754224946 27 Periya Soliyambakkam Village Ellaiyan & Babu 8754224946 Elavur -

106Th MEETING

106th MEETING TAMIL NADU STATE COASTAL ZONE MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY Date: 25.07.2019 Venue: Time: 11.00 A.M Conference Hall, 2nd floor, Namakkal Kavinger Maligai, Secretariat, Chennai – 600 009 INDEX Agenda Pg. Description No. No. 01 Confirmation of the minutes of the 105th meeting of the Tamil Nadu State 1 Coastal Zone Management Authority held on 21.05.2019 02 The action taken on the decisions of 105th meeting of the Authority held on 12 21.05.2019 03 Construction of 30” OD Underground Natural Gas Pipeline of M/s. Indian Oil Corporation Ltd., from Ennore LNG Terminal situated inside Kamarajar Port Limited, Ennore, Tiruvallur district to Salavakkam Village, Uthiramerur Taluk, 15 Kancheepuram district 04 Construction of doubling of Railway Line between Existing Holding Yard No.1 at Ch.00m (Near Bridge No.5) to Entry of Container Rail Terminal Yard of M/s. Kamarajar Port Ltd., at Athipattu, Puzhuthivakkam and Ennore Village of 17 Ponneri Taluk, Tiruvallur district 05 Erection of Transmission tower and transmission line for 400 KV power evacuation line from SEZ to Ennore Thermal Power Station (ETPS) expansion project, SEZ to North Chennai (NC) Pooling Station, EPS expansion project to NC Pooling Station and 765 KV Power evacuation line from North Chennai 19 Thermal Power Station-Stage-III (NCTPS-III) to NC Pooling Station at Ennore by M/s. Tamil Nadu Transmission Corporation Limited (TANTRANSCO) 06 Revalidation of CRZ Clearance for the Foreshore facilities viz., Pipe Coal Conveyor, Cooling Water Intake and Outfall Pipeline for the project and ETPS Expansion Thermal Power Project (1x660 MW) proposed within the existing 21 ETPS at Ernavur Village, Thiruvottiyur Taluk, Tiruvallur district proposed by TANGEDCO 07 Proposed Container Transit Terminal at S.F.No.1/3B3, Pulicat Road, Kattupalli Village, Tiruvallur district by M/s. -

Urban and Landscape Design Strategies for Flood Resilience In

QATAR UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING URBAN AND LANDSCAPE DESIGN STRATEGIES FOR FLOOD RESILIENCE IN CHENNAI CITY BY ALIFA MUNEERUDEEN A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Science in Urban Planning and Design June 2017 © 2017 Alifa Muneerudeen. All Rights Reserved. COMMITTEE PAGE The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Alifa Muneerudeen defended on 24/05/2017. Dr. Anna Grichting Solder Thesis Supervisor Qatar University Kwi-Gon Kim Examining Committee Member Seoul National University Dr. M. Salim Ferwati Examining Committee Member Qatar University Mohamed Arselene Ayari Examining Committee Member Qatar University Approved: Khalifa Al-Khalifa, Dean, College of Engineering ii ABSTRACT Muneerudeen, Alifa, Masters: June, 2017, Masters of Science in Urban Planning & Design Title: Urban and Landscape Design Strategies for Flood Resilience in Chennai City Supervisor of Thesis: Dr. Anna Grichting Solder. Chennai, the capital city of Tamil Nadu is located in the South East of India and lies at a mere 6.7m above mean sea level. Chennai is in a vulnerable location due to storm surges as well as tropical cyclones that bring about heavy rains and yearly floods. The 2004 Tsunami greatly affected the coast, and rapid urbanization, accompanied by the reduction in the natural drain capacity of the ground caused by encroachments on marshes, wetlands and other ecologically sensitive and permeable areas has contributed to repeat flood events in the city. Channelized rivers and canals contaminated through the presence of informal settlements and garbage has exasperated the situation. Natural and man-made water infrastructures that include, monsoon water harvesting and storage systems such as the Temple tanks and reservoirs have been polluted, and have fallen into disuse. -

The Benchmark-January 2021

Approved by AICTE, DTE, Maharashtra State Government and Affiliated to Mumbai University Accredited with “B+” Grade by NAAC The Benchmark JANUARY 2021 Vol 03 Edition 07 Patrons Dr. Jitendra B. Patil - Campus Director Mr. Rajesh Dubey - H.O.D., Civil ` POST BEARERS KATHIPARA JUNCTION Mr. Rahul Patil (Pg. – 02) - General Secretary Ms. Takshika Bhut - Joint Secretary Mr. Chirag Gangani - Treasurer Mr. Brijesh Chauhan - Technical Head Concrete Cafe Mr. Praneeth Hegde Seismic River - Documentation Head Mr. Rohan Talekar - Creative Head Gravel Garden Ms. Sakshi Dubey - Discipline Head Department Vision Ms. Vrushti Makwana - Hospitality Head Grouting Gym To excel in every area of Civil Engineering, inculcate research oriented study to explore hidden talent. Mr. Dhruv Parmar Canvas Providing Opportunity to display creativity, out of the box thinking & innovativeness, aimed at providing cutting edge Ms. Pranali Gudekar (Pg. – 08) technology for sustainable development. - Marketing Head Tension Tower Department Mission Mr. Yagnesh Jamvecha Ms. Khushi Patil Volume Providing qualified, motivated faculties to deliver the content - Public Relation Officer using updated teaching methodology, inviting industry experts from various areas to disseminate subject knowledge Village in Civil Engineering. EDITORS Motivating students to undertake the Research Oriented studies, participate in competitions at all levels, grasping new Mr. Brijesh Chauhan Editor’s Desk techniques and methods which can be improved on further. Ms. Kalpita Chafekar Conducting and participating in seminars, workshops and We are pleased to present January 2021 edition of training programs with a view to make the students industry ready and improve their employability factor for global career benchmark.In this edition you all will find an article ahead. -

To, Prof. T. Haque, Dr. N. P. Shukla, Dr. H. C. Sharatchandra, Mr

To, Prof. T. Haque, Dr. N. P. Shukla, Dr. H. C. Sharatchandra, Mr. V. Suresh, Dr. V. S. Naidu Mr. B. C. Nigam Dr. Manoranian Hota Dr. Dipankar Saha Dr. Jayesh Ruparelia Dr. (Mrs.) Mayuri H. Pandya Dr. M. V. Ramana Murthy Prof. Dr. P.S.N. Rao Mr. Kushal Vashist February 5, 2019 Dear Sirs and Ma’am, I write to you from Citizen consumer and civic Action Group (CAG), a 33 year old non-profit, non-political and professional organisation that works towards protecting citizens' rights in consumer, civic and environmental issues and promoting good governance processes including transparency, accountability, and participatory decision-making. This is with regard to an application for consideration of the Proposed Revised Master Plan Development of Kattupalli Port, by Marine Infrastructure Developer Private Limited (MIDPL) at Kattupalli, Tiruvallur District, Tamil Nadu, which is to be considered in the 38th EAC Meeting (CRZ- Infrastructure 2 Projects), on February 6, 2019. It is required of Project Proponents to consider alternate sites, when presenting a proposal. This has been enshrined in the MoEF’s guideline for a Project Feasibility Report, which requires it to detail ‘alternate sites to be considered, and the basis for choosing the proposed site, particularly the environmental considerations gone into it should be highlighted’. For the project in question though, alternate sites have not been considered. In fact, the consultant concedes that ‘no other site selection criterion has been considered’ for the project, since it is a strategic location with an existing draft, reliable power supply and allows for multimodal connectivity, among other things [3.1]. -

Ennore Port, 16 Km North of Chennai Port, Another Erosion Problem Was Emerged and Similar Issues Like Chennai Port Are on the Way

i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The coastline of Chennai with a hinterland of 20km offer a variety of environmental issues and problems, which need integrated management. These include the coastal erosion and accretion, pollution from human settlement and industries, loss of aesthetics in tourism beaches and declining fishery resources. The ICMAM Project Directorate undertook the task of analysing above problems and prepared integrated management solutions, which will help to solve these problems and also avoidance of occurrence of such problems in future. It is well known that the shoreline along Chennai coast is subjected to oscillations due to natural and man made activities. After construction of Chennai port, coast north of port is eroded and 350 hectares land is lost into sea. The river Cooum that carries domestic sewage is closed due to accretion of sand south port. State Government resorted to short term measures for protecting coastal stretch of length 6 km at Royapuram with sea wall and the erosion problem shifted to further north. Now with the construction of Ennore port, 16 km North of Chennai port, another erosion problem was emerged and similar issues like Chennai port are on the way. If, no intervention is planned, threat to ecologically sensitive Pulicat Lake is inevitable. North Ennore Coast is already experiencing increased wave action and the naturally formed protection barriers, the “Ennore Shoals”, may likely to be disturbed by construction of Port. Baseline data reveal that the Ennore creek on south of Ennore port is experiencing increased siltation. Since the available information on Ennore coast is not sufficient for working out suitable measures, a research project entitled “Shoreline management along Ennore” has been formulated to conduct detailed field and model investigations on various dynamical aspects (water level variations, currents & circulation, tides, waves, bathymetric variations, sediment transport, shoreline changes etc) of Ennore coast covering Ennore creek to Pulicat mouth. -

Marine Infrastructure Developer Private Limited (MIDPL)

Marine Infrastructure Developer Private Limited (MIDPL) Executive Summary PROPOSED REVISED MASTER PLAN DEVELOPMENT OF KATTUPALLI PORT December 2020 PREPARED BY C1161303 NABET ACCREDITED Certificate No: NABET/EIA/2023/RA 0175 RP003, Rev. A L&T Infrastructure Engineering Ltd. Client: Marine Infrastructure Developer Private Limited (MIDPL) Project: Proposed Revised Master Plan Project No.: Development of Kattupalli Port C1161303 Title: Document No.: Rev.: Executive Summary RP003 A This document is the property of L&T Infrastructure Engineering Ltd. and File path: must not be passed on to any person or body not authorised by us to receive it l:\ports\2016\c1161303 - ceia kattupalli port nor be copied or otherwise made use of either in full or in part by such person or expansion\outputs\reports\rp003-executive summary\13.12.2020\executive body without our prior permission in writing. summary-14.12.2020.docx Notes: 1. Revision Details: SAP TKS A 13.12.2020 Second Submission SNV BRT S SNV SAP TKS 0 26.10.2020 First Submission Sd/- Sd/- Sd/- IRR BRT S Init. Sign. Init. Sign. Init. Sign. Rev. Date Details Prepared Checked Approved Table of Contents Proposed Revised Master Plan Development of Kattupalli Port C1161303 Executive Summary RP003 rev. A TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction .....................................................................................................................................1 2 Project Site ......................................................................................................................................1 -

Brainstorming Meet on Chennai Water Managemnet

BRAINSTORMING MEET ON CHENNAI WATER MANAGEMNET Organised by REGIONAL METEOROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT & INDIAN METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY, CHENNAI CHAPTER. ECOSYSTEM BASED SOLUTIONS FOR DISASTER RISK REDUCTION IN CHENNAI CITY AND IT’S SUB URBS. By T. Kanthimathinathan, Water Resources Management (Hydrology & Flood Control) Consultant, T.N.D.R.R.D.A. CHENNAI 03.08.2019. HYDROLOGICAL FEATURES OF CHENNAI AND ITS SUBURBS AN OVERVIEW NATURAL DRAINAGE SYSTEMS OF CHENNAI BASIN Chennai City and its suburbs in Thiruvallur and Kancheepuram Districts lies in Chennai Basin. The main rivers flowing in Chennai basin are, 1. Araniyar 2. Kosasthalaiyar 3. Cooum 4. Adayar There are only five outlets for discharging the entire runoff from Chennai Basin into Bay of Bengal are, 1. Pulicat Creek (Araniyar River) 2. Ennore Creek (Kosasthalaiyar River) 3. Cooum River mouth (Cooum River) 4. Adayar River mouth (Adayar River) 5. Kovalam Creek (Muttukadu & Pallikkaranai isolated water sheds) NATURAL DRAINAGE SYSTEMS OF CHENNAI BASIN Contnd…. The estuarine coastal fragile eco-systems available behind the above outlets of Chennai Basin are, 1. Pulicat Lake behind Pulicat creek 2. Ennore backwaters behind Ennore Creek 3. Pallikkaranai marsh land and Muttukadu backwaters behind Kovalam Creek. Chennai Basin is divided into the following eight sub-basins according to the drainage pattern 1. Gummidipoondi Sub basin 2. Araniyar Sub basin 3. Kosasthalaiyar Sub basin 4. Nagariyar Sub basin 5. Nandhiyar Sub basin 6. Cooum Sub basin 7. Adayar Sub basin & 8. Kovalam Sub basin INTER BASIN TRANSFER SYSTEMS AVAILABLE FOR SUPPLEMENTING CHENNAI BASIN WATER NEEDS. Krishna River to Chennai Basin : From Srisailam reservoir to Somasila reservoir through SRMC, link cannal, Velugodu balancing Reservoir, TGP main canal and CMP Canal. -

Puzhuthivakkam Survey No

Via Email on 24th October Ongoing encroachment of Kosasthalai River and backwaters by Kamarajar Port – Puzhuthivakkam Survey No. 143 & Athipattu Survey No. 354 To: Commissioner, Revenue Administration State Disaster Management Authority Government of Tamil Nadu To: Commissioner, State Disaster Management Authority Government of Tamil Nadu To: Collector Thiruvallur District To: RDO, Office of the Collector Thiruvallur District To: Commissioner, Greater Corporation of Chennai Ripon Building, Chennai To: Secretary (E&F)Chairman, State Coastal Zone Management Authority Government of Tamil Nadu To: Chairman, Expert Appraisal Committee (CRZ Ports)Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change New Delhi 24 October, 2017 Dear Sir/Madam: Subject: Ongoing encroachment of Kosasthalai River and backwaters by Kamarajar Port – Puzhuthivakkam Survey No. 143 & Athipattu Survey No. 354 Despite desperate pleas by us and fisherfolk, and manifest evidence that the Kosasthalai River is being encroached upon, Kamarajar Port Ltd is going about its business of irreversibly destroying more and more of the wetlands. These are images from 21 October, 2017. Where the rest of the city is busy clearing up clogged waterways in preparation for the Northeast monsoon, Kamarajar Port is encroaching on what is left of Kosasthalai's backwaters secure in its impunity. We have already briefed you, via personal meetings, letters or phone conversations, about the illegal recommendation for clearance by the State Coastal Zone Management Authority for diversion of Kosasthalai River for construction of coal yards, warehouse zones and car parks by KPL. That clearance was aided by using a fraudulent map that denies the existence of Kosasthalaiyar north of the estuary - http://www.newindianexpress.com/states/tamil-nadu/2017/jul/25/illegal-map-used-to- clear-port-plan-in-ennore-creek-1633204.html The ongoing activity has been projected as part of Phase III Masterplan expansion and the application for CRZ clearance is pending pending at the Expert Appraisal Committee, MoEFCC. -

Research Paper Geo Spatial Application

Academia Journal of Scientific Research 6(10): 382-393, October 2018 DOI: 10.15413/ajsr.2018.0152 ISSN 2315-7712 ©2018 Academia Publishing Research Paper Geo spatial application in impact assessment of oil spill on sensitive coastal resources: A case study of oil spill accident in Chennai (India) Accepted 30th October, 2018 ABSTRACT An accidental discharge of oil in the near shore regions requires a comprehensive post- spill assessment of environmental impact and biological effects for planning the response and post mitigation efforts. This study discusses Remote Sensing and GIS based impact assessment on the coastal resources coupled with model simulation. The oil spill impact was estimated through spill simulation and incorporated environmental sensitivity index as level of concern to assess the impact. The best guess of the trajectory simulation was used to assess the spatial distribution and concentration of oil on the coastal region to notify the area and resources to analyze the impact of the spilled oil. Under the simulation of weathering process, it is estimated that 94% oil is stranded on the shoreline. S. Arockiaraj1*, Mary Angelin1, M. C. There has been attempt to document the oil on the water surface using remote John Milton1, G. Bhaskaran2 sensing data collected by Sentinel 1A, 2A and Landsat/OLI and trajectory of the released oil. Near real time detection of oil trajectory and quantification using 1PG & Research Department of remote sensing data help with possible oil landing information. The potential Advanced Zoology and Biotechnology, Loyola College, effect of oil on species was assessed through Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon Chennai 600034. -

MINUTES of the 228Th MEETING of the EXPERT APPRAISAL

MINUTES OF THE 228th MEETING OF THE EXPERT APPRAISAL COMMITTEE FOR PROJECTS RELATED TO COASTAL REGULATION ZONE HELD ON 29th NOVEMBER, 2019 AT INDIRA PARYAVARAN BHAWAN, MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, FOREST AND CLIMATE CHANGE, NEW DELHI. The 228th Meeting of the Expert Appraisal Committee for projects related to Coastal Regulation Zone was held on 29.11.2019 at Brahmaputra Conference Hall, Vayu Block, 1st Floor, Indira Paryavaran Bhawan, New Delhi. The members present are: 1. Dr. Deepak Arun Apte - Chairman 2. Dr. M.V Ramana Murthy - Member 3. Dr. Anil Kumar Singh - Member 4. Dr. V. K. Jain - Member 5. Dr. Anuradha Shukla - Member 6. Dr. Manoranjan Hota - Member 7. Dr. Rajesh Shah - Member 8. Ms. Bindhu Manghat - Member Shri Prabhakar Singh, Shri Narendra Surana, Shri N.K. Gupta, Shri. N.K. Verma and Shri Sanjay Singh were absent. Shri. W. Bharat Singh, Member Secretary was unable to attend as he had to attend to an inter-ministerial assignment on off shore wind energy programme of the Government of India. The meeting was therefore officiated by Dr. P. Saranya as Member Secretary. The deliberations held and the decisions taken are as under: 2.0 CONFIRMATION OF THE MINUTES OF THE LAST MEETING. The Committee having noted that the Minutes of the 226th meeting are in order, confirmed the same with suggestions that in case any typographical/grammatical errors are noticed in due course, the same may be corrected suitably. 3.0 FRESH PROPOSALS: 3.1 Proposal for Construction of doubling of Railway Line between Existing Holding Yard No.1 at Ch.00 m (Near Bridge No.5) to Entry of Container Rail Terminal Yard of M/s Kamarajar Port Ltd.