Is Facebook an Effective Crisis Communication Tool for Companies?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Protection Strategy Plan

DEEPWATER HORIZON OIL SPILL PROTECTION STRATEGY PLAN CITY OF APALACHICOLA JULYS, 2010 Van W. Johnson, Sr., Mayor Brenda Ash, Commissioner Betty Webb,City Administrator John M. Bartley, Sr., Commissioner J. Patrick Floyd, City Attorney Frank Cook, Commissioner Lee Mathes, City Clerk James L. Elliott, Commissioner CITY OF APALACmCOLAHOTLINE 850-653-1526 www.cityofapalachicola.com. OFFICIAL WEBSITE FOR UNIFIED COMMAND: www.deepwaterhorizonresponse.com. A LETTER FROM MAYOR VAN JOHNSON Dear Citizens of Historic Apalachicola, After looking at the failure of many of the efforts of BP and those working with BP to the west of us here in Apalachicola to locate and contain the approaching oil spill and prevent it from coming ashore in these communities (Pensacola Beach, etc.), and after reviewing the projections of scientists from following the dye put in the oil erupting from the spill site, I am convinced that we must act immediately to defend and protect ourselves from this oil. We here in Apalachicola already know from our fight with the Army Corps of Engineers and upstream water takers over the illegal taking of our fresh water flow down the Apalachicola River, particularly during drought, that "no one is going to protect your backyard like you're going to protect your backyard." (Quote from Tony Kennon, Mayor, Orange Beach, AL- 6/14/10) We have been asking BP and our government for assistance to enable Apalachicola to protect against this oil for weeks, mostly without any response. Some of our sister cities to the west experienced the same delay and after five weeks the oil came to their shores and their focus has now been turned to clean-up rather than keeping the oil from getting to them. -

Mississippi Canyon 252 Oil Spill Submerged Aquatic Vegetation Tier 2 Pre-Assessment Post Spill Exposure Characterization Plan

Deepwater Horizon/MC 252 Oil Spill November 8, 2011 SA V Tier 2 Preassessment Plan Mississippi Canyon 252 Oil Spill Submerged Aquatic Vegetation Tier 2 Pre-Assessment Post Spill Exposure Characterization Plan Natalie Cosentino-Manning(National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration) Eva DiDonato (National Park Service) Jud Kenworthy (National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration) Shahrokh Rouhaiii (NewFields) Michael Wild (NewFields) Paul Carlson (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission) Laura Yarbro (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission) Amy Uhrin (National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration) Ken Heck (Dauphin Is. Sea Lab) Gail French Fricano (Industrial Economics) For the MC 252 NRDA Submerged Aquatic Vegetation Technical Working Group Mississippi Canyon 252 Trustees Final Version November 8, 2011 First Drafted May 25, 2010 Comments and questions should be addressed to: Natalie Cosentino-Manning (Natalie.c-manning@ [email protected] ) DWH-AR0013315 Deepwater Horbon/MC 252 Oil Spill S/1 y Tier 2 Preassessment Plan Novembers. 2011 Mississippi Canyon 252 Incident Submerged Aquatic Vegetation Tier 2 Pre-Assessment Post-Spill Exposure Characterization Plan Approval o f this Tier 2 Post-Spill Exposure Characterization Plan is for the /,/ obt^ning data for the Natural Resource Damage Assessment. Each party rescues it 'srieht to interpretation and analysis o f any data collected pursuant to this This plan will be implemented consistent with existing Trustee regulations and aalial^^ah applicable state andjederal permits must be obtained prior to conducting work rjrtf WomedllK Tm m s' d^lonK^ve‘dH‘^ 2 o u l^ ld V p l and addenda. By signing this workplan and agreeing to fund the work addendn h T preliminary conclusions articulated in the workplan or addenda, including addenda developed subsequent to the signature date APPROVED: fer t\/\Cj l2n\1 ent of Commerce Trustee Representative; Date a lag I aoicx. -

Ke Nako – Es Ist Zeit

AZ 3900 Brig • Samstag, 12. Juni 2010 • Nr. 133 • 170. Jahrgang • Fr. 2.20 SEAT GOOD STUFF SONDERMODELLE MIT BIS ZU FR. 2’520 .– PREISVORTEIL. 3.9% Superzins- Leasing*** Ibiza Good Stuff ab Fr. 21’700 .–* oder Fr. 244.–/Monat*** TomTom • 16" Alu-Felgen • Bluetooth Leon Good Stuff ab Fr. 25’250 .–** oder Fr. 284.–/Monat*** Multifunktionslenkrad • 16" Alu-Felgen • Tempomat Auto Neubrück AG Gmeisand 3922 Stalden Tel. 027 952 20 01 www.walliserbote.ch • Redaktion Telefon 027 922 99 88 • Abonnentendienst Telefon 027 948 30 50 • Mengis Annoncen Telefon 027 948 30 40 • Auflage 25 261 Expl. Gute Wintersaison KOMMENTAR Walliser Bergbahnen zufrieden mit Ergebnis Ke Nako – Wir sind L e B o u v e r e t. – (wb) Bei nen. Es habe sich aber ge- der GV der Walliser Bergbah- zeigt, dass die Bahnen offen- alles Afrikaner nen konnte ein gutes Ergebnis bar krisenresistent sind. Wei- Er hat wahrlich schon andere der Wintersaison 2009/2010 ter wurde an der Generalver- Zeiten durchgemacht. An der präsentiert werden, dies trotz sammlung über ein einheitli- Seite von Nelson Mandela. In pessimistischer Voraussagen. ches Tarifsystem für alle Es ist Zeit diesem Land mit seiner men- «Die Vorzeichen für die Sai- Bergbahnen diskutiert. Eine schenverachtenden Vergangen- son, wie etwa die Wirt- Arbeitsgruppe hat bereits ein heit, das sich seine Geburt zur schaftskrise oder die Bedro- neues Tarifmodell für Aufent- Die Fussball-WM am Kap der Guten Hoffnung ist eröffnet Regenbogen-Nation so sehr er- hung durch die Grippe A halte ab zwei Tagen und mehr leiden musste. H1N1 waren nicht gut», so ausgearbeitet. -

(850) 921-0217 Florida Deepwater

CHARLIE CRIST SECRETARY MICHAEL W. SOLE DAVID HALSTEAD Governor Florida Department of Environmental Protection State Coordinating Officer MEDIA ADVISORY: TUESDAY, JUNE 15, 2010 CONTACT: PUBLIC INFORMATION (ESF 14): (850) 921-0217 FLORIDA DEEPWATER HORIZON RESPONSE JUNE 15, 2010 TALLAHASSEE – Under the leadership of Governor Charlie Crist, the State Emergency Response Team and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) are actively coordinating and responding to the Deepwater Horizon incident. The following is a summary of state and BP response actions to date, as well as tips for residents and visitors to take precautions both pre and post-landfall. Landfall Reports and Predictions: On June 14, dime to five inch-sized tar balls and tar patties were found in widely scattered areas of Northwest Florida. Perdido Pass and Pensacola Pass will be closed with the tide to prevent oil from entering inland waters. Boom will be deployed across each Pass at flood tide (water coming in) and removed at ebb tide (water going out). o Boaters in areas where skimming is being conducted, or where boom has been set, have been requested to maintain no-wake speeds. o Based on oil activity recently, the United States Coast Guard's Captain of the Port for Sector Mobile authorized the official closure of Perdido Pass and Pensacola Pass. These waterways will be manned to allow access to necessary vessel traffic. Perdido Pass and Pensacola Pass will be open for vessel traffic during low tide. See NOAA tide predictions. o Boat traffic needing access in or out of boom locations, should call 1-850-736- 2261. -

United States District Court Eastern District of Louisiana

Case 2:10-md-02179-CJB-DPC Document 13983 Filed 01/06/15 Page 1 of 7 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA In re: Oil Spill by the Oil Rig MDL NO. 2179 ADeepwater Horizon@ in the Gulf of Mexico, on April 20, 2010 SECTION J Applies to: 10-4182, 10-4183, 13-2645, JUDGE BARBIER 13-2646, 13-2647, 13-2813 MAGISTRATE JUDGE SHUSHAN ORDER [Regarding Alabama Damage Cases – Alabama Motion to Dismiss ( Rec. doc. 13513)] Before the Court is the motion of the State of Alabama to dismiss Defendants’ set-off claims, or in the alternative, motion to strike set-off affirmative defenses. Rec. doc. 13513. BACKGROUND The Deepwater Horizon oil spill began on April 20, 2010. The well was declared sealed on September 19, 2010. In August 2010, BPXP established the Gulf Coast Claims Facility. BPXP reports that between April 20, 2010 and February 28, 2014 it paid: (1) approximately $1.8 billion to individuals and businesses in Alabama through various claims processes; and (2) approximately $115 million in payments to Alabama or its agencies. It reports spending more than $14 billion on spill response and cleanup activities, including block grants to state and local governments. The grants to Alabama included: (1) May 2010 - $25 million block grant; (2) June 2010 - $25 million for implementation of its Area Contingency Plan; (3) May 2010 - $15 million for tourism promotion; (4) March 2011 - $16 million for tourism promotion; (5) August 2010 - $12 million to the Department of Mental Health; and (6) August 2010 - $7 million to the Alabama Gulf Coast Convention and Visitor’s Bureau for tourism promotion.1 1 BPXP’s first supplemental response to Alabama’s interrogatory no. -

ALERT FINAL NCP Rules 150422

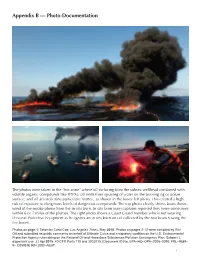

Appendix B –– Photo-Documentation The photos were taken in the “hot zone” where oil surfacing from the subsea wellhead combined with volatile organic compounds like BTEXs, oil mists from spraying of water on the burning rig or ocean surface, and oil aerosols (fine particulate matter), as shown in the lower left photo. This created a high risk of exposure to dangerous levels of dangerous compounds. The top photo clearly shows boats down- wind of the smoke plume from the in situ burn. In situ burn team captains reported they were sometimes within 6 or 7 miles of the plumes. The right photo shows a Coast Guard member who is not wearing Personal Protective Equipment as he ignites an in situ burn on oil collected by the two boats towing the fire boom. Photos on page 1: Taken by Carol Coe, Los Angeles Times, May 2010. Photos on pages 2-12 were compiled by Riki Ott and submitted as public comments on behalf of Ultimate Civics and a signatory coalition on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency rulemaking on the National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan, Subpart J, dispersant use. 22 Apr 2015. 40 CFR Parts 110 and 3002015, [Document ID No. EPA–HQ–OPA–2006–0090; FRL–9689– 9– OSWER] RIN 2050–AE87. 1 On May 26, 2010, seven fishermen on in-situ burn teams for the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster were taken by Medevac life-flights from their fishing boats directly to West Jefferson Medical Center in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana. Burning oil concentrates toxic PAHs; first responders typically wear a full- face positive-pressure self-contained breathing apparatus and protective suit for fighting oil fires. -

Lack of Basic Research Cripples Scientists When Assessing Toll of BP Oil Spill on Gulf's Natural System | Al.Com

Lack of basic research cripples scientists when assessing toll of BP oil spill on Gulf's natural system | al.com JOBS AUTOS REAL ESTATE RENTALS CLASSIFIEDS OBITUARIES FIND N SAVE LOCAL BUSINESSES Sign in | Join Alabama 55° Set your local edition » 5-day | Satellite NEWS BUSINESS SPORTS H.S. SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT LIVING Lack of basic research cripples scientists when assessing toll of BP oil spill on Gulf's natural system 6 comments By Ben Raines | [email protected] Email the author | Follow on Twitter on April 20, 2013 at 7:10 AM, updated April 20, 2013 at 8:56 AM Most Comments Most Read College football's $500 million question: 547 Who's going to pick the playoff teams? View full size Schools of multiple species of baby fish are swarming around the rocks at Perdido Pass this week. The tiny fish, all under an inch, prove reproduction is occurring, but scientists can't say whether adult Auburn A-Day Live Updates: Orange 35, populations have returned to normal after the BP oil spill. (Ben 400 Blue 14; Auburn smashes attendance Raines/[email protected]) record with 83,401 (final) Three years after the BP oil spill, scientists are left scratching their heads when asked if Boston bomb suspect in serious condition, populations of sea creatures in the Gulf of Mexico have returned to normal. 285 unable to answer questions No one knows the answer to that most central question, the scientists say, because of a lack of basic monitoring of marine populations, both before and after the spill. A party revolt? Democratic Party Chairman 185 Mark Kennedy is resigning -

Quantification of Water and Salt Exchanges in a Tidal Estuary

Water 2015, 7, 1769-1791; doi:10.3390/w7051769 OPEN ACCESS water ISSN 2073-4441 www.mdpi.com/journal/water Article Quantification of Water and Salt Exchanges in a Tidal Estuary Janesh Devkota 1 and Xing Fang 2,* 1 Dynamic Solutions International LLC, Edmonds, WA 98020, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Civil Engineering, Auburn University, Auburn, AL 36849-5337, USA * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-334-844-8778; Fax: +1-334-844-6290. Academic Editor: Say-Leong Ong Received: 28 January 2015 / Accepted: 20 April 2015 / Published: 24 April 2015 Abstract: A calibrated three-dimensional hydrodynamic model was applied to study subtidal water and salt exchanges at various cross sections of the Perdido Bay and Wolf Bay system using the Eulerian decomposition method from 6 September 2008 to 13 July 2009. Salinity, velocity, and water levels at each cross section were extracted from the model output to compute flow rates and salt fluxes. Eulerian analysis concluded that salt fluxes (exchanges) at the Perdido Pass and Dolphin Pass cross sections were dominated by tidal oscillatory transport FT, whereas shear dispersive transport FE (shear dispersion due to vertical and lateral shear transport) was dominant at the Perdido Pass complex, the Wolf-Perdido canal, and the lower Perdido Bay cross sections. The flow rate QF and total salt transport rate FS showed distinct variation in response to complex interactions between 3 −1 discharges from upstream rivers and tidal boundaries. QF and FS ranged from −619 m ·s (seaward) to 179 m3·s−1 (landward) and −13,480–6289 kg·s−1 at Perdido Pass when river discharges ranged 11.0–762.5 m3·s−1 in the 2008–2009 simulation period. -

Temporal and Spatial Assessment of Pahs in Water, Sediment, and Oysters As a Result of the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1-1-2012 Temporal and Spatial Assessment of PAHs in Water, Sediment, and Oysters as a Result of the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Meghan Christina Dailey University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Dailey, Meghan Christina, "Temporal and Spatial Assessment of PAHs in Water, Sediment, and Oysters as a Result of the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1334. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1334 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Temporal and Spatial Assessment of PAHs in Water, Sediment, and Oysters as a Result of the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Mississippi Meghan Dailey June 2012 Copyright Meghan Dailey 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude and sincere thanks to Dr. Kristine Willett for the support through all the frustrations this project has given us. Also, for being wonderful and fun! I would also like to thank Dr. Marc Slattery for funding me while working on this project, as well for his guidance and support. I am also thankful for Dr. Bonnie Avery for agreeing to be on my committee and being involved in the program. She is a wonderful asset. -

Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill

State of Alabama DEEPWATER HORIZON OIL SPILL S OGRES REPOR PR T ON TI A R O T S E R te da Up 2018 2 ALABAMA DEEPWATER HORIZON RESTORATION | 2018 UPDATE Table of Contents 1 Letter from Governor Kay Ivey 2 Letter from Commissioner Chris M. Blankenship 3 Executive Summary 4 Understanding the DWH Restoration Processes in Alabama 6 Restoration Goals Replenish and Protect Living Coastal and Marine Resources 12 Support and Enhance Community Resilience 25 Provide and Enhance Economic Development & Infrastructure 29 Restore, Conserve and Enhance Habitat 34 Provide and Enhance Recreation/Public Access 47 Restore Water Quality 55 Provide Planning Support 62 Project Status 63 Looking to the Future 69 Additional Alabama Restoration Information 70 MicDesign ALABAMA DEEPWATER HORIZON RESTORATION | 2018 UPDATE 1 LETTER FROM GOVERNOR IVEY We are blessed and fortunate to live in the most beautiful state in the country. Alabama boasts tremendous natural diversity, including over 4,500 species of plants and animals. In April 2010, that beauty was marred when the Deepwater Horizon exploded, killing 11 people and impacting our natural resources and way of life in coastal Alabama. Since the earliest days of the spill, the State of Alabama has been engaged in the recovery of Alabama’s natural resources and coastal economy. In partnership with our state, federal and local partners as well as thousands of Alabamians, we have worked to plan and implement restoration projects that will not only provide benefits to those of us who call Alabama home today, but also preserve our resources and strengthen the economy for future generations of Alabamians. -

Mississippi Canyon 252 Incident Submerged Aquatic Vegetation Tier 1 Pre-Assessment Plan Pre-Impact Baseline Characterization

Deepwater Horizon/MC 252 Oil Spill SAV Tier 1 Preassessment Plan Mississippi Canyon 252 Oil Spill Submerged Aquatic Vegetation Tier 1 Pre-Assessment Plan Pre-Impact Baseline Characterization Natalie Cosentino-Manning (National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration) Eva DiDonato (National Park Service) Shahrokh Rouhani (Newfields) Alexandra Van Geel (Industrial Economics) Paul Carlson (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission) Laura Yarbro (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission) Jud Kenworthy (National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration) Amy Uhrin (National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration) Ken Heck (Dauphin Is. Sea Lab) Sean Meehan (National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration) Mark Fonseca (National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration) Katherine von Stackleberg (Industrial Economics) In coordination with Chris Pfeifer (Entrix) Russ Burge (Entrix) John Dimitry (Entrix) For the MC 252 NRDA Submerged Aquatic Vegetation Technical Working Group Mississippi Canyon 252 Trustees Draft Version 7.0 Date September 28, 2010 Originally drafted May 11, 2010 1 Deepwater Horizon/MC 252 Oil Spill SA V Tier] Preassessment Plan Mississippi Canyon 252 Incident Submerged Aquatic Vegetation Tier 1 Pre-Assessment Plan Pre-Impact Baseline Characterization Approval ofthis Tier I Pre-Assessment plan isfor the purposes ofobtaining datafor the Natural Resource Damage Assessment. Each party reserves its right to produce its own independent interpretation and analysis ofany data collectedpursuant to this workplan. This plan will be implemented consistent -

Perdido River and Bay SWIM Plan Northwest Florida Water Management District

Perdido River and Bay Surface Water Improvement and Management Plan October 2017 Program Development Series 17-07 Northwest Florida Water Management District Perdido River and Bay Surface Water Improvement and Management Plan October 2017 Program Development Series 17-07 NORTHWEST FLORIDA WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT GOVERNING BOARD George Roberts Jerry Pate John Alter Chair, Panama City Vice Chair, Pensacola Secretary-Treasurer, Malone Gus Andrews Jon Costello Marc Dunbar DeFuniak Springs Tallahassee Tallahassee Ted Everett Nick Patronis Bo Spring Chipley Panama City Beach Port St. Joe Brett J. Cyphers Executive Director Headquarters 81 Water Management Drive Havana, Florida 32333-4712 (850) 539-5999 Crestview Econfina Milton 180 E. Redstone Avenue 6418 E. Highway 20 5453 Davisson Road Crestview, Florida 32539 Youngstown, FL 32466 Milton, FL 32583 (850) 683-5044 (850) 722-9919 (850) 626-3101 Perdido River and Bay SWIM Plan Northwest Florida Water Management District Acknowledgements This document was developed by the Northwest Florida Water Management District under the auspices of the Surface Water Improvement and Management (SWIM) Program and in accordance with sections 373.451-459, Florida Statutes. The plan update was prepared under the supervision and oversight of Brett Cyphers, Executive Director and Carlos Herd, Director, Division of Resource Management. Funding support was provided by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund. The assistance and support of the NFWF is gratefully acknowledged. The authors would like to especially recognize members of the public, as well as agency reviewers and staff from the District and from the Ecology and Environment, Inc., team that contributed to the development of this plan.