Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Hamilton Planning and Economic Development Department Planning Division

CITY OF HAMILTON PLANNING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT PLANNING DIVISION TO: Chair and Members Planning Committee COMMITTEE DATE: January 16, 2018 SUBJECT / REPORT NO: Preliminary Screening for the Request to Designate 650 and 672 Sanatorium Road, Hamilton, Under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act (Ward 8) (PED18001) WARD(S) AFFECTED: Ward 8 PREPARED BY: Jeremy Parsons 905-546-2424 Ext. 1214 SUBMITTED BY: Steve Robichaud Director, Planning and Chief Planner Planning and Economic Development Department SIGNATURE: RECOMMENDATION (a) That Council direct and authorize staff to undertake a Cultural Heritage Assessment of 650 and 672 Sanatorium Road, Hamilton, shown on Appendix “A” to Report PED18001, to determine whether the property is of cultural heritage value worthy of designation under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act; (b) That the Cultural Heritage Assessment work be assigned a high priority and be added to staff’s work plan for completion and presentation to the Hamilton Municipal Heritage Committee (HMHC) no later than December 31, 2018, as per the attached Appendix “G” to Report PED18001; (c) That should the Cultural Heritage Assessment determine that 650 and 672 Sanatorium Road, Hamilton, is of cultural heritage value or interest, a Statement of Cultural Heritage Value or Interest and Description of Heritage Attributes be prepared by staff for Council’s consideration for designation under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act; (d) Pursuant to Section 27(1.2) of the Ontario Heritage Act, that Council direct staff to add the respective buildings located at 650 and 672 Sanatorium Road, shown in Appendix “A” of Report PED18001, to the Register of Property of Cultural Heritage Value or Interest (the “Register”), following consultation with the HMHC as per the Council-approved Designation Process (see Appendix “D” to Report PED18001); OUR Vision: To be the best place to raise a child and age successfully. -

Draft Recreational Trails Master Plan

Hamilton Recreational Trails Master Plan DRAFT | NOVEMBER 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................... i-v Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................................ vi 1.0 Study Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 A History of Trails in Hamilton ..................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Trail Vision, Goals, & Objectives for the City of Hamilton ............................................................ 2 1.3 The Benefi ts of Trail Development ............................................................................................. 3 1.4 The Organization of the Master Plan Report ............................................................................... 5 2.0 The Trails Network ........................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Understanding what has Already Been Done: The Previous Trail Master Plan (2007) ................... 7 2.2 The Trail Master Plan Update Process ....................................................................................... 7 2.2.1 Trails Master Plan Opportunities ............................................................................. -

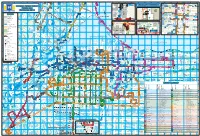

HSR Customer C D O W Hunter St

r r C D e k a r n o r s D o t b is t t r r a l Mo L s C n e D m e te s e e n g v n S r R o h i P M C o a C s m h o o r K W O i e C lo s ms a M a m n F d g s lk d u ff o A s i a H te on r e n C i r u a Dr t y N te a lic l r e a g y o v L rm ic C de 's u n r t R e P a a e D F A ld l s ti a Cumberlandd t o l n L v r t u a n iti n W i l r C in r gh a y n a u e o D D e o a D C Dr e w m S d r r a s m t A M n e r o C v a C C M e v A S F lv R h e l R c t t lm l v Guelph Line e or v e W G A r c r re a P a v v Laurentian en L n R en A R i c a l d s a yatt Rd b a r t D v A c e ni A t a s C r d e a T n t ie ie A t u C C o r k t h rt n D i r t r d g C a e la Dr C il r a r e a p e R e C M y A kvi D C T y a e n v O a d R w r C l a L o k B t w w F O A e e k T o L v l e o a La r a d a u r v n k f le R a is w D e or a d d to ic r sid t t Pear id P Fi c k Spruce e C C M s k M ge h P v S A t C ree gsbrid o D l Brant St M Kin s er H r ap New St Pi O im v T s o A n h G A m le e ak o t r r Ct Fisherv n r l e h a l C w r e D C n w il l s e C o l L i o o D o w o D r ve o r N o h d t n l p t M d Harvester Rd D r e a R ic r w C to r D y e y L d h w l o n t olson Ct o r o e M a p A l c f s e B s v il m z B a s R u u d r d ln B P a d U G a u r r o a er le W W e a v C n r t p c rtv T H l R D C ko e r S iew B mesbu d P r nd r y R B H ay Dr A r d r F a ingw D Concession 8 E C m y i a D o r l e u e t m C n R h s i t r e J tl C e S w e d o a t r C l l W n d c t l A a h C e a s s r l n t i d n e a l rpi D R J r e n e li s to r A r vl e e le n v n C t n v i t d g o C ffe -

SNAP IT! Are You Hosting an Event in Ward 8? Sometimes Pictures Speak Louder Than Words

ISSUE 7 • SPRING/SUMMER 2013 Dear Friends, Welcome to the 2013 Summer Issue of Saying Goodbye to The Honourable the Whitehead Report. As always, I am pleased to provide you with updates on what’s happening in and around our Lincoln M. Alexander community, and to share information On October 26, 2012 the City of Hamilton had the opportunity to about issues that affect our city. honour and remember a beloved Hamiltonian and Canadian; As your Councillor, I am committed to Ontario's 24th Lieutenant Governor, the Honourable Lincoln providing information, implementing Alexander. A number of agencies and individuals should be resolutions and sharing dialogue on thanked and recognized for their involvement in planning and issues of concern to you. That’s why coordinating this incredible state funeral including Mayor and every year I host over 22 issue and Mrs. Bratina, police, HSR, Hamilton Entertainment and budget oriented neighbourhood Convention Facilities Inc., parking, traffic and many other City meetings throughout the ward. I also departments, volunteers and residents. It was an honour to meet area residents each month during celebrate a proud Hamiltonian and to show our great City and my constituency days at Westcliffe residents to the rest of Canada. Mall. Photo Credit: Nick Westoll For those looking to contact me online, my new website with blog and Twitter posts is a great source for the latest Construction: Road Work in your Area information and happenings in and There are a number of construction projects taking place in • Sanatorium Rd. - Redfern to Chedmac/Rice around City Hall. You can also interact Ward 8, the main one to draw your attention to is the closure • West 5th - LINC to Marlowe • with me and other ward 8 residents by of the Queen Street Hill from June 01 to August 30th. -

41 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

41 bus time schedule & line map 41 41a Chedoke Hospital View In Website Mode The 41 bus line (41a Chedoke Hospital) has 7 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) 41a Chedoke Hospital: 12:00 AM - 11:20 PM (2) Gage at Industrial: 3:28 PM (3) Gage at Industrial Via Kenilworth: 12:25 AM - 11:51 PM (4) Gage at Industrial Via Ottawa: 12:03 AM - 11:33 PM (5) Lime Ridge Mall: 2:07 PM - 3:29 PM (6) Meadowlands: 12:20 AM - 11:40 PM (7) Mohawk at Upper James: 1:05 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 41 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 41 bus arriving. Direction: 41a Chedoke Hospital 41 bus Time Schedule 79 stops 41a Chedoke Hospital Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:28 AM - 11:47 PM Monday 5:02 AM - 11:20 PM Industrial Opposite Depew 42 Industrial Drive, Hamilton Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:20 PM Gage at Burlington Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:20 PM 950 Burlington Street, Hamilton Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:20 PM At 377 Gage Friday 12:00 AM - 11:20 PM 377 Gage Avenue, Hamilton Saturday 12:00 AM - 11:28 PM Gage at Beach 337 Gage Avenue, Hamilton Beach at Albemarle 140 Beach Road, Hamilton 41 bus Info Direction: 41a Chedoke Hospital Beach at Rowanwood Stops: 79 11 Rowanwood Street, Hamilton Trip Duration: 49 min Line Summary: Industrial Opposite Depew, Gage at Beach Opposite Gate 3 Burlington, At 377 Gage, Gage at Beach, Beach at 276 Beach Road, Hamilton Albemarle, Beach at Rowanwood, Beach Opposite Gate 3, Beach at Ottawa, Ottawa at Beach, Beach at Beach at Ottawa Woodleigh, Beach at Bayƒeld, Grenfell at Martimas, -

2018 Tax Supported Final Capital Budget

2018 Tax Supported Final Capital Budget Book 2 2018 Capital Budget Detail Sheets FCS17099 2018-2027 PROJECT SUMMARIES & 2018 CAPITAL PROJECT DETAIL SHEETS BY DEPARTMENT 2018 CAPITAL BUDGET TABLE OF CONTENTS & LIST APPENDICES Appendix Page Name Description Number 2018 Capital Project Detail Sheets & 2018-2027 Project Summaries by Department By Ward 2018-2027 Projects Grouped by Ward, by Multi-Wards & by City Wide 1 C&E Serv Community & Emergency Services Department Overview 40 Hamilton Fire Department 42 Housing Services 48 Long Term Care Homes 53 Community Services - Other Divisions 61 Hamilton Paramedic Service 64 Plan & Dev Planning & Economic Development Department Overview 68 Economic Development 70 Growth Management 72 Parking Services 75 Planning Services 81 Planning - General Manager's Office 85 Tourism & Culture 87 Urban Renewal 97 2018 CAPITAL BUDGET TABLE OF CONTENTS & LIST APPENDICES Appendix Page Name Description Number Boards Outside Boards & Agencies Department Overview 108 CityHousing Hamilton 110 H.C.A. & Westfield Heritage Village 113 Hamilton Beach Rescue (HBRU) 117 Hamilton Public Library 120 Police 124 Council Council Initiatives Department Overview 130 Area Rating Special Capital Reinvestment 132 Council Strategic Projects 143 City Manager City Manager Department Overview 146 City Manager 147 Human Resources 151 Corp Serv Corporate Services Department Overview 156 Finance 158 Information Technology (IT) 163 City Clerk 170 Customer Service and POA 173 2018 CAPITAL BUDGET TABLE OF CONTENTS & LIST APPENDICES Appendix -

Together Saving Changing

TOGETHER WE ARE SAVING AND CHANGING LIVES ANNUAL REPORT 2017/2018 OUR COMMUNITY PROGRAMS Legal Advocacy & Resource Centre for Women www.intervalhousehamilton.org VISION, MISSION & VALUES Our Vision Our Values Board of Directors • Empowerment IHOH will be an innovative (2017/18) leader providing compassionate • Confidentiality & Privacy care and sustainable, highly- • Health & Safety President integrated services in our quest • Diversity & Inclusion for violence free lives for women, Peter Bieling children and communities. • Equity for Women • Effective & Responsive Treasurer Our Mission Communication Diana Simmons Violence free lives for all women, • Responsible & children and communities. Professional Service Secretary Angela Slade A Balanced Score Financial Directors Karen Vandenbeukel Card Approach to • Development Plan Strategic Goals of… • Increase Revenue Vanessa Vrbanic Funding & Sources • Innovative Leadership Leah Hogan • Compassionate Care Krista Schmid • Sustainability Learning & Growth • Highly Integrated Services Pankaj Kasturi • Performance Management System in Place Michaela Walker Women & Community • Improvement in Health, Stakeholder Safety and Wellness of Staff Teams Board of Directors • Quality and Accessible • Innovation and (2018/19) Compassionate Service Knowledge Generation • Highly Integrated President Partnerships • Advocacy & Systems Peter Bieling Navigation • Prevention & Education Treasurer Diana Simmons Internal Process • Proactive Human Secretary Resource Plan Angela Slade • Standard Operating Practices Across -

The History of the Department of Anesthesia Historical Timeline - Manuscript

The History of the Department of Anesthesia Historical Timeline - Manuscript 1812 The Burlington Heights and Emigrant Hospital is a temporary military medical barrack established in 1812 (due to the absence of any municipal hospital in Hamilton at this time) that treated the military, arriving immigrants, and poor residents of Hamilton. Temporary buildings for medical treatment for the most common illnesses such as smallpox, cholera, and typhus were also set up along the bayshore; however, these primitive medical centers were closed in 1849 due to the opening of Hamilton’s first municipal hospital in 18481. 1844 Nitrous Oxide is introduced into the medical community as an anesthetic agent by a Connecticut Dentist by the name of Horace Wells; however, its anesthetic properties were not recorded to have been put to general surgical use until twenty years after its discovery. Nitrous Oxide and its dependency on oxygen to function, leads to the development of an intermittent flow nitrous oxide and oxygen anesthetic gas machine in the 1910. The first successful use of the gas machine and nitrous oxide in surgery is attributed to Dr. E.I. McKessen.2 1846 The City of Hamilton is Incorporated. Ether is introduced into the medical community as one of the first anesthetic agents in 1846; however, the earliest recording that points to its anesthetic properties were made in 1540 by a German botanist named Valerius Cordus. Cordus synthesized ether and discovered its (similar) anesthetic effects via inhalation, when he would use it to enliven recreational parties, or as they have been nick named, “ether frolicks”.3 Historically speaking, there remains debate and contention over who the first discoverer of ether is as Crawford W. -

Download the October. 2017 Issue in PDF Format

PRIME ADVERTISING SPACE AVAILABLE! Contact [email protected] for information on how to get YOUR business noticed! FAREWELL TO ST. LUKE’S THANKSGIVING SUBMITTED BY BRIAN ROULSTON SUBMITTED BY KEN HIRTER of Christ’s Church if he could fund a new parish for them. Once funded the group pur- chased a wood frame build- ing which was at one time used as Methodist Episcopal Church then moved it to the present-day site of St. Luke’s. It opened as the 6th Episcopal place for worship in Hamilton Thanksgiving is defined as: “the act of giving thanks, on July 9,1882. The sermon grateful acknowledgment or favors, an expression of was presided by Dr. Mockridge thanks, a public celebration in acknowledgment of and the Reverend F.E Howitt. divine favor or kindness” This church would serve the community for 7 years. Thanksgiving weekend this year starts on Saturday October the 07th to Monday October the 09th 2017. By 1883 the church became self- supported. Plans were But did you know…… made to build a new more Long before Europeans settled in North America, modern brick church. The new festivals of thanks and celebrations of harvest took church with a seating capacity place in Europe in the month of October. The very The Parish Church of St.Luke’s, founded in 1822 of 300 opened to worshipers in 1889. first Thanksgiving celebration took place in Canada and stands proudly on the corner of John and Ma- when Martin Frobisher, an Explorer from England Between 1916 and 1922 the parish hall was built arrived in Newfoundland in 1578. -

Respiratory Medicine at Mcmaster University, Hamilton, Ontario: 1968 to 2013

HIstorY OF RESPIratorY MEDICINE IN canada Respiratory medicine at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario: 1968 to 2013 Norman L Jones MD FRCP FRCPC, Paul M O’Byrne MB FRCPC FRSC NL Jones, PM O’Byrne. Respiratory medicine at McMaster DISTRIBUTION OF INHALED particles: Michael University, Hamilton, Ontario: 1968 to 2013. Can Respir J Newhouse and Myrna Dolovich used inhaled radiolabelled aerosols to 2014;21(6):325. study the distribution of inhaled particles and their clearance in nor- mal subjects, smokers and patients with chronic obstructive pulmo- The medical school at McMaster University (Hamilton, Ontario) was nary disease. They developed the aerochamber, and were the first to conceived in 1965, and admitted the first class in 1969. John Evans radiolabel therapeutic aerosols to distinguish the effects of peripheral became the founding Dean and he invited EJ Moran Campbell to be versus central deposition. Particle deposition and clearance were the first Chairman of the Department of Medicine. Moran Campbell, shown to be impaired in ciliary dyskinesia and cystic fibrosis. already a world figure in respiratory medicine and physiology, arrived DYSPNEA: Moran Campbell and Kieran Killian measured psycho- at McMaster in September 1968, and he invited Norman Jones to be physical estimates of the sense of effort in breathing in studies of Coordinator of the Respiratory Programme. loaded breathing and exercise to show that dyspnea increased as a At that time, Hamilton had a population of 300,000, with two full- power function of both duration and intensity of respiratory muscle time respirologists, Robert Cornett at the Hamilton General Hospital contraction, and in relation to reductions in respiratory muscle and Michael Newhouse at St Joseph’s Hospital. -

Sovera Health Information Managment

Case Study _experience the commitment TM Sovera® Health Information Management Hamilton Health Sciences (HHS) CGI Sovera Health Information Solution provides anytime, anywhere online access to patient health records at Hamilton Health Sciences. Hamilton Health Sciences (HHS) is a family of hospitals serving the 468,000 citi- zens of the city of Hamilton and the more than two million residents of Central- South Ontario, Canada. HHS is one of Canada’s largest teaching hospitals, and its 10,000 staff, physicians and volunteers provide a comprehensive range of acute, non-acute and specialized services, catering to health care needs from preconcep- tion through to aging adults. Chedoke Hospital, Hamilton General Hospital, Hender- son General Hospital, McMaster Children’s Hospital and McMaster University Medical Centre are all part of the HHS family, along with the Juravinski Cancer Centre, the most comprehensive centre for cancer care and research in the entire region. THE CHALLENGE Although Hamilton Health Sciences operates its five hospitals on four campuses as a single, combined facility, each hospital still had its own independent health re- cords department, resulting in significant challenges managing patient health re- cords. A patient at HHS could end up with as many as four different health records, for “With the help of CGI’s example, requiring considerable effort by medical staff when pulling together the healthcare knowledge and comprehensive clinical picture of that patient’s history they use to ensure delivery experience, our implementation of the best possible care. of the Sovera solution gave us a With the consolidation of the hospitals and the growing number of patients, the pa- giant step forward in bridging per health records at HHS were becoming very difficult to manage. -

HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT for Proposed Scenic Trails Apartment Lands, 1 Redfern Avenue Hamilton, Ontario

HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR Proposed Scenic Trails Apartment Lands, 1 Redfern Avenue Hamilton, Ontario April 1, 2015 BARRY BRYAN ASSOCIATES Architects, Engineers, Project Managers 250 Water Street Telephone: 905 666-5252 Suite 201 Toronto: 905 427-4495 Whitby, Ontario Fax: 905 666-5256 Canada Email: [email protected] L1N 0G5 Web Site: www.bba-archeng.com HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR Proposed Scenic Trails Apartment Lands, 1 Redfern Avenue Hamilton, Ontario Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE ..............................................................................................................1 2.0 SITE LOCATION AND DESCRIPTION ........................................................................................................2 3.0 HISTORY OF SITE .....................................................................................................................................3 4.0 DESCRIPTION AND EVALUATION OF CULTURAL HERITAGE RESOURCES ...............................................4 5.0 DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT ........................................................................................5 6.0 PLANNING CONTEXT ...............................................................................................................................6 7.0 EVALUATION OF IMPACT ON HERITAGE RESOURCES.............................................................................7 8.0 MITIGATION OF HERITAGE IMPACT........................................................................................................8