Conquerors in Cute Clothing Analysis of Colonialism, Empathy, and Japanese Soft Power in Pikmin 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nintendo Co., Ltd

Nintendo Co., Ltd. Financial Results Briefing for the Nine-Month Period Ended December 2013 (Briefing Date: 1/30/2014) Supplementary Information [Note] Forecasts announced by Nintendo Co., Ltd. herein are prepared based on management's assumptions with information available at this time and therefore involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Please note such risks and uncertainties may cause the actual results to be materially different from the forecasts (earnings forecast, dividend forecast and other forecasts). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Consolidated Statements of Income Transition million yen FY3/2010 FY3/2011 FY3/2012 FY3/2013 FY3/2014 Apr.-Dec.'09 Apr.-Dec.'10 Apr.-Dec.'11 Apr.-Dec.'12 Apr.-Dec.'13 Net sales 1,182,177 807,990 556,166 543,033 499,120 Cost of sales 715,575 487,575 425,064 415,781 349,825 Gross profit 466,602 320,415 131,101 127,251 149,294 (Gross profit ratio) (39.5%) (39.7%) (23.6%) (23.4%) (29.9%) Selling, general and administrative expenses 169,945 161,619 147,509 133,108 150,873 Operating income 296,656 158,795 -16,408 -5,857 -1,578 (Operating income ratio) (25.1%) (19.7%) (-3.0%) (-1.1%) (-0.3%) Non-operating income 19,918 7,327 7,369 29,602 57,570 (of which foreign exchange gains) (9,996) ( - ) ( - ) (22,225) (48,122) Non-operating expenses 2,064 85,635 56,988 989 425 (of which foreign exchange losses) ( - ) (84,403) (53,725) ( - ) ( - ) Ordinary income 314,511 80,488 -66,027 22,756 55,566 (Ordinary income ratio) (26.6%) (10.0%) (-11.9%) (4.2%) (11.1%) Extraordinary income 4,310 115 49 - 1,422 Extraordinary loss 2,284 33 72 402 53 Income before income taxes and minority interests 316,537 80,569 -66,051 22,354 56,936 Income taxes 124,063 31,019 -17,674 7,743 46,743 Income before minority interests - 49,550 -48,376 14,610 10,192 Minority interests in income -127 -7 -25 64 -3 Net income 192,601 49,557 -48,351 14,545 10,195 (Net income ratio) (16.3%) (6.1%) (-8.7%) (2.7%) (2.0%) - 1 - Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

Super Smash Bros. Melee) X25 - Battlefield Ver

BATTLEFIELD X04 - Battlefield T02 - Menu (Super Smash Bros. Melee) X25 - Battlefield Ver. 2 W21 - Battlefield (Melee) W23 - Multi-Man Melee 1 (Melee) FINAL DESTINATION X05 - Final Destination T01 - Credits (Super Smash Bros.) T03 - Multi Man Melee 2 (Melee) W25 - Final Destination (Melee) W31 - Giga Bowser (Melee) DELFINO'S SECRET A13 - Delfino's Secret A07 - Title / Ending (Super Mario World) A08 - Main Theme (New Super Mario Bros.) A14 - Ricco Harbor A15 - Main Theme (Super Mario 64) Luigi's Mansion A09 - Luigi's Mansion Theme A06 - Castle / Boss Fortress (Super Mario World / SMB3) A05 - Airship Theme (Super Mario Bros. 3) Q10 - Tetris: Type A Q11 - Tetris: Type B Metal Cavern 1-1 A01 - Metal Mario (Super Smash Bros.) A16 - Ground Theme 2 (Super Mario Bros.) A10 - Metal Cavern by MG3 1-2 A02 - Underground Theme (Super Mario Bros.) A03 - Underwater Theme (Super Mario Bros.) A04 - Underground Theme (Super Mario Land) Bowser's Castle A20 - Bowser's Castle Ver. M A21 - Luigi Circuit A22 - Waluigi Pinball A23 - Rainbow Road R05 - Mario Tennis/Mario Golf R14 - Excite Truck Q09 - Title (3D Hot Rally) RUMBLE FALLS B01 - Jungle Level Ver.2 B08 - Jungle Level B05 - King K. Rool / Ship Deck 2 B06 - Bramble Blast B07 - Battle for Storm Hill B10 - DK Jungle 1 Theme (Barrel Blast) B02 - The Map Page / Bonus Level Hyrule Castle (N64) C02 - Main Theme (The Legend of Zelda) C09 - Ocarina of Time Medley C01 - Title (The Legend of Zelda) C04 - The Dark World C05 - Hidden Mountain & Forest C08 - Hyrule Field Theme C17 - Main Theme (Twilight Princess) C18 - Hyrule Castle (Super Smash Bros.) C19 - Midna's Lament PIRATE SHIP C15 - Dragon Roost Island C16 - The Great Sea C07 - Tal Tal Heights C10 - Song of Storms C13 - Gerudo Valley C11 - Molgera Battle C12 - Village of the Blue Maiden C14 - Termina Field NORFAIR D01 - Main Theme (Metroid) D03 - Ending (Metroid) D02 - Norfair D05 - Theme of Samus Aran, Space Warrior R12 - Battle Scene / Final Boss (Golden Sun) R07 - Marionation Gear FRIGATE ORPHEON D04 - Vs. -

Sega Megadrive European PAL Checklist

The Sega Megadrive European PAL Checklist □ 688 Attack Sub □ Crack Down □ Gunship □ Aaahh!!! Real Monsters □ Crue Ball □ Gunstar Heroes □ Addams Family Values □ Cutthroat Island □ Gynoug □ Addams Family, The □ Cyberball □ Hard Drivin' □ Adventures of Batman & Robin, The □ Cyborg Justice □ Hardball (Box) □ Adventures of Mighty Max, The □ Daffy Duck in Hollywood □ Hardball III □ Aero the Acro-Bat □ Dark Castle □ Hardball '94 □ Aero the Acro-Bat 2 □ David Robinson's Supreme Court □ Haunting, The □ After Burner 2 □ Davis Cup World Tour □ Havoc □ Aladdin □ Death and Return of Superman, The □ Hellfire □ Alex Kidd in the Enchanted Castle □ Decap Attack □ Herzog Zwei □ Alien 3 □ Demolition Man □ Home Alone □ Alien Soldier □ Desert Demolition starring Road Runner □ Hook □ Alien Storm □ Desert Strike: Return to the Gulf □ Hurricanes □ Alisia Dragoon □ Dick Tracy □ Hyperdunk □ Altered Beast □ Dino Dini's Soccer □ Immortal, The □ Andre Agassi Tennis □ Disney Collection, The □ Incredible Crash Dummies, The □ Animaniacs □ DJ Boy □ Incredible Hulk, The □ Another World □ Donald in Maui Mallard □ Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade □ Aquatic Games starring James Pond □ Double Clutch □ International Rugby □ Arcade Classics □ Double Dragon (Box) □ International Sensible Soccer □ Arch Rivals □ Double Dragon 3: The Arcade Game □ International Superstar Soccer Deluxe □ Ariel: The Little Mermaid □ Double Hits: Micro Machines & Psycho Pinball □ International Tour Tennis □ Arnold Palmer Tournament Golf □ Dr. Robotnik's Mean Bean Machine □ Izzy's Quest for the -

Nintendo Co., Ltd

Nintendo Co., Ltd. Financial Results Briefing for the Six-Month Period Ended September 2013 (Briefing Date: 10/31/2013) Supplementary Information [Note] Forecasts announced by Nintendo Co., Ltd. herein are prepared based on management's assumptions with information available at this time and therefore involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Please note such risks and uncertainties may cause the actual results to be materially different from the forecasts (earnings forecast, dividend forecast and other forecasts). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Semi-Annual Consolidated Statements of Income Transition million yen FY3/2010 FY3/2011 FY3/2012 FY3/2013 FY3/2014 Apr.-Sept.'09 Apr.-Sept.'10 Apr.-Sept.'11 Apr.-Sept.'12 Apr.-Sept.'13 Net sales 548,058 363,160 215,738 200,994 196,582 Cost of sales 341,759 214,369 183,721 156,648 134,539 Gross profit 206,298 148,791 32,016 44,346 62,042 (Gross profit ratio) (37.6%) (41.0%) (14.8%) (22.1%) (31.6%) Selling, general, and administrative expenses 101,937 94,558 89,363 73,506 85,321 Operating income 104,360 54,232 -57,346 -29,159 -23,278 (Operating income ratio) (19.0%) (14.9%) (-26.6%) (-14.5%) (-11.8%) Non-operating income 7,990 4,849 4,840 5,392 24,708 (of which foreign exchange gains) ( - ) ( - ) ( - ) ( - ) (18,360) Non-operating expenses 1,737 63,234 55,366 23,481 180 (of which foreign exchange losses) (664) (62,175) (52,433) (23,273) ( - ) Ordinary income 110,613 -4,152 -107,872 -47,248 1,248 (Ordinary income ratio) (20.2%) (-1.1%) (-50.0%) (-23.5%) (0.6%) Extraordinary income 4,311 190 50 - 1,421 Extraordinary loss 2,306 18 62 23 18 Income before income taxes and minority interests 112,618 -3,981 -107,884 -47,271 2,651 Income taxes 43,107 -1,960 -37,593 -19,330 2,065 Income before minority interests - -2,020 -70,290 -27,941 586 Minority interests in income 18 -9 -17 55 -13 Net income 69,492 -2,011 -70,273 -27,996 600 (Net income ratio) (12.7%) (-0.6%) (-32.6%) (-13.9%) (0.3%) - 1 - Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

Best Wishes to All of Dewey's Fifth Graders!

tiger times The Voice of Dewey Elementary School • Evanston, IL • Spring 2020 Best Wishes to all of Dewey’s Fifth Graders! Guess Who!? Who are these 5th Grade Tiger Times Contributors? Answers at the bottom of this page! A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R Tiger Times is published by the Third, Fourth and Fifth grade students at Dewey Elementary School in Evanston, IL. Tiger Times is funded by participation fees and the Reading and Writing Partnership of the Dewey PTA. Emily Rauh Emily R. / Levine Ryan Q. Judah Timms Timms Judah P. / Schlack Nathan O. / Wright Jonah N. / Edwards Charlie M. / Zhu Albert L. / Green Gregory K. / Simpson Tommy J. / Duarte Chaya I. / Solar Phinny H. Murillo Chiara G. / Johnson Talula F. / Mitchell Brendan E. / Levine Jojo D. / Colledge Max C. / Hunt Henry B. / Coates Eve A. KEY: ANSWER KEY: ANSWER In the News Our World............................................page 2 Creative Corner ..................................page 8 Sports .................................................page 4 Fun Pages ...........................................page 9 Science & Technology .........................page 6 our world Dewey’s first black history month celebration was held in February. Our former principal, Dr. Khelgatti joined our current Principal, Ms. Sokolowski, our students and other artists in poetry slams, drumming, dancing and enjoying delicious soul food. Spring 2020 • page 2 our world Why Potatoes are the Most Awesome Thing on the Planet By Sadie Skeaff So you know what the most awesome thing on the planet is, right????? Good, so you know that it is a potato. And I will tell you why the most awesome thing in the world is a potato, and you will listen. -

Ikaruga (For Gamecube)

Robin Ramirez, Jens Wouters – GDD1 Game Analysis Title: Ikaruga (for Gamecube) Release dates: Ikaruga (Arcade Japan) – December 20, 2001 Ikaruga (Dreamcast) – September 5, 2002 Ikaruga (Gamecube) – May 23, 2003 Ikaruga (Xbox Live Arcade) – April 9, 2008 Editor: Treasure Co. Ltd Designers: Hiroshi Iuci Director, BG Graphic Design, Music Atsutomo Nakagawa Co-Director, Main Programmer Yasushi Suzuki Character, Object Design Satoshi Murata Sound Effect, BGM Data Edit Masato Maegawa Executive Producer Publishers: Ikaruga (Arcade Japan) -> SEGA Ikaruga (Dreamcast) -> ESP Ikaruga (Gamecube) -> Atari Ikaruga (Xbox Live Arcade) -> Treasure Co. Ltd Type of game: shoot’em up Category: arcade Rating: 11+ Main target audience: shoot’em up hardcore arcade gamers Number of players: single player (1), co-op (2) Duration of game session: about 20, 30 minutes for the whole game Short description / Pitch: It’s a shoot’em up where you have to change polarization to dodge enemy fire and make your way trough 5 stages of innovative level design. Game analysis of Ikaruga (Gamecube) Robin Ramirez, Jens Wouters Page 1 of 9 GDD1 Executive summary Theme Scenario / Characters 2 Theme Universe / Themes/ Uniformity 3 Mechanisms Originality / Innovation / Freshness 4 Mechanisms Gameplay / Replayability 4 Mechanisms Rhythm 4 Mechanisms Player Experience 5 Mechanisms Rules System 5 Mechanisms Game Flow / Phases / Player’s Turn 4 Mechanisms Scoring System 5 Editorial style Terms, specific syntax 3 Editorial style Tone 4 Editorial style Contents 3 Graphics Logotype 4 Graphics Style guide, graphics 5 Graphics Cover, Packaging 3 Graphics Components 4 1: Very Poor; 2: Poor; 3: Fair; 4: Good; 5: Very Good Theme: Scenario / Characters It’s hard to know the story by just playing this Gamecube version. -

![CYCA3;4 Is a Post-Prophase Target of the APC/CCCS52A2 E3-Ligase Controlling Formative Cell 2 Divisions in Arabidopsis [W]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5306/cyca3-4-is-a-post-prophase-target-of-the-apc-cccs52a2-e3-ligase-controlling-formative-cell-2-divisions-in-arabidopsis-w-965306.webp)

CYCA3;4 Is a Post-Prophase Target of the APC/CCCS52A2 E3-Ligase Controlling Formative Cell 2 Divisions in Arabidopsis [W]

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.17.995506; this version posted March 19, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 CYCA3;4 Is a Post-Prophase Target of the APC/CCCS52A2 E3-Ligase Controlling Formative Cell 2 Divisions in Arabidopsis [W] 3 AUTHORS: 4 Alex Willems,a,b Jefri Heyman,a,b Thomas Eekhout,a,b Ignacio Achon,a,b Jose Antonio Pedroza- 5 Garcia,a,b Tingting Zhu,a,b Lei Li,a,b Ilse Vercauteren,a,b Hilde Van den Daele,a,b Brigitte van de 6 Cotte,a,b Ive De Smet,a,b and Lieven De Veyldera,b,1 7 AFFILIATIONS: 8 aDepartment of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics, Ghent University, Ghent, B-9052, 9 Belgium 10 bCenter for Plant Systems Biology, VIB, Ghent, B-9052, Belgium 11 ORCID IDs: 12 0000-0002-7211-8388 (A.W.); 0000-0003-3266-4189 (J.H.); 0000-0002-2878-1553 (T.E.); 0000- 13 0002-4553-1257 (I.A.); 0000-0001-8258-0157 (J.A.P.G); 0000-0002-0904-7636 (T.Z.); 0000- 14 0002-1820-9852 (L.L.); 0000-0001-9561-8468 (I.V.); 0000-0002-4271-6694 (H.V.d.D.); 0000- 15 0001-7236-9243 (B.v.d.C.); 0000-0003-4607-8893 (I.D.S.); 0000-0003-1150-4426 (L.D.V.) 16 RUNNING TITLE: CYCA3;4 control by APC/CCCS52A2 17 ONE-SENTENCE SUMMARY: 18 Timely post-prophase breakdown of the Arabidopsis cyclin CYCA3;4 by the Anaphase Promoting 19 Complex/Cyclosome is essential for meristem organization and development. -

Animal Crossing

Alice in Wonderland Harry Potter & the Deathly Hallows Adventures of Tintin Part 2 Destroy All Humans: Big Willy Alien Syndrome Harry Potter & the Order of the Unleashed Alvin & the Chipmunks Phoenix Dirt 2 Amazing Spider-Man Harvest Moon: Tree of Tranquility Disney Epic Mickey AMF Bowling Pinbusters Hasbro Family Game Night Disney’s Planes And Then There Were None Hasbro Family Game Night 2 Dodgeball: Pirates vs. Ninjas Angry Birds Star Wars Hasbro Family Game Night 3 Dog Island Animal Crossing: City Folk Heatseeker Donkey Kong Country Returns Ant Bully High School Musical Donkey Kong: Jungle beat Avatar :The Last Airbender Incredible Hulk Dragon Ball Z Budokai Tenkaichi 2 Avatar :The Last Airbender: The Indiana Jones and the Staff of Kings Dragon Quest Swords burning earth Iron Man Dreamworks Super Star Kartz Backyard Baseball 2009 Jenga Driver : San Francisco Backyard Football Jeopardy Elebits Bakugan Battle Brawlers: Defenders of Just Dance Emergency Mayhem the Core Just Dance Summer Party Endless Ocean Barnyard Just Dance 2 Endless Ocean Blue World Battalion Wars 2 Just Dance 3 Epic Mickey 2:Power of Two Battleship Just Dance 4 Excitebots: Trick Racing Beatles Rockband Just Dance 2014 Family Feud 2010 Edition Ben 10 Omniverse Just Dance 2015 Family Game Night 4 Big Brain Academy Just Dance 2017 Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer Bigs King of Fighters collection: Orochi FIFA Soccer 09 All-Play Bionicle Heroes Saga FIFA Soccer 12 Black Eyed Peas Experience Kirby’s Epic Yarn FIFA Soccer 13 Blazing Angels Kirby’s Return to Dream -

Wind Waker Manual

OFFICIAL NINTENDO POWER PLAYER'S GUIDE AVAILABLE AT YOUR NEAREST RETAILER! WWW.NINTENDO.COM Nintendo of America Inc. P.O. Box 957, Redmond, WA 98073-0957 U.S.A. www.nintendo.com IN S T R U C T IO N B O O K LET 50520A IN S T R U C T IO N B O O K LET PRINTED IN USA W A R N IN G : P L E A S E C A R E FU L L Y R E A D T HE S E P A R A T E P R E C A U T IO N S B O O K L E T IN C L U D E D W IT H T HIS P R O D U C T WARNING - Electric Shock B E FO R E U S IN G Y O U R N IN T E N D O ® HA R D W A R E S Y S T E M , To avoid electric shock when you use this system: G A M E D IS C O R A C C E S S O R Y . T HIS B O O K L E T C O N T A IN S IM P O R T A N T S A FE T Y IN FO R M A T IO N . Use only the AC adapter that comes with your system. Do not use the AC adapter if it has damaged, split or broken cords or wires. -

From Girlfriend to Gamer: Negotiating Place in the Hardcore/Casual Divide of Online Video Game Communities

FROM GIRLFRIEND TO GAMER: NEGOTIATING PLACE IN THE HARDCORE/CASUAL DIVIDE OF ONLINE VIDEO GAME COMMUNITIES Erica Kubik A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2010 Committee: Radhika Gajjala, Advisor Amy Robinson Graduate Faculty Representative Kristine Blair Donald McQuarie ii ABSTRACT Radhika Gajjala, Advisor The stereotypical video gamer has traditionally been seen as a young, white, male; even though female gamers have also always been part of video game cultures. Recent changes in the landscape of video games, especially game marketers’ increasing interest in expanding the market, have made the subject of women in gaming more noticeable than ever. This dissertation asked how gender, especially females as a troubling demographic marking difference, shaped video game cultures in the recent past. This dissertation focused primarily on cultures found on the Internet as they related to video game consoles as they took shape during the beginning of the seventh generation of consoles, between 2005 and 2009. Using discourse analysis, this dissertation analyzed the ways gendered speech was used by cultural members to define not only the limits and values of a generalizable video game culture, but also to define the idealized gamer. This dissertation found that video game cultures exhibited the same biases against women that many other cyber/digital cultures employed, as evidenced by feminist scholars of technology. Specifically, female gamers were often perceived as less authoritative of technology than male gamers. This was especially true when the concept “hardcore” was employed to describe the ideals of gaming culture. -

Jennifer Dewinter, Shigeru Miyamoto: Super Mario Bros., Donkey Kong

98 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PLAY • FALL 2016 pily travel with her as she traverses the As the video game industry ages, the need art and craft of designing for social play, to discuss game designers and their contri- physical play, and more. Still, there is the butions becomes paramount. While there niggling (and inevitable?) question of what are several ways of looking at and con- exactly constitutes “meaningful choice.” textualizing past milestones in the game After all, even the most complex games industry—such as the books in the MIT offer players only a handful of options in Press Platform Studies series—Jennifer the grand scheme of things and, there- deWinter and Carly Kocurek’s Influential fore, the promise rather than the reality Video Game Designers series, published of choice. But I suppose that will have to by Bloomsbury, is an attempt to move for- be a question for another book. ward the conversation between the design- For the uninitiated, I expect that How ers and their games over an entire career. Games Move Us will be pleasant reading, In the series’ debut book, Shigeru and it might make a good opening text in Miyamoto, deWinter examines the cre- an Introduction to Game Design course or ator of Mario, Donkey Kong, Pikmin, and find its way onto a friend’s summer read- many other games to figure out how the ing list. More experienced readers, though, designer’s life and interests affected his will likely be better served by exploring game designs. Miyamoto is a fitting icon Isbister’s traditional scholarly work, upon to begin a series like this, considering his which How Games Move Us is based and contributions to games are both large and examples of which are cited in the book’s significant. -

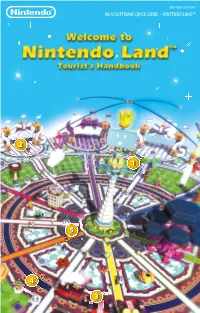

Wii U SOFTWARE QUICK GUIDE NINTENDO LAND™

MAAWUPALCPUKV Wii U SOFTWARE QUICK GUIDE NINTENDO LAND™ 2 1 5 4 3 The Legend of Zelda: Battle Quest 1 to 4 Players Enter a world of archery and swordplay and vanquish enemies left, right and centre in a valiant quest for the Triforce. Recommended for team play! 1–3 Some modes require the Wii Remote™ Plus. Pikmin Adventure 1 to 5 Players As Olimar and the Pikmin, work together to brave the dangers of a strange new world. Smash blocks, defeat enemies and overcome the odds to make it safely back to your spaceship! 1–4 Team Attractions Team Metroid Blast 1 to 5 Players Assume the role of Samus Aran and take on dangerous missions on a distant planet. Engage fearsome foes on foot or in the ying Gunship and blast your way to victory! Some modes require the 1–4 Wii Remote Plus and Nunchuk™. Mario Chase 2 to 5 Players Step into the shoes of Mario and his friends the Toads, and get set for a heart-racing game of tig. Can Mario outrun and outwit his relentless pursuers for long enough? 1–4 Luigi’s Ghost Mansion 2 to 5 Players In a dark, dank and creepy mansion, ghost hunters contend with a phantasmal foe. Shine light on the ghost to extinguish its eerie presence before it catches you! 1–4 Animal Crossing: Sweet Day 2 to 5 Players Competitive Attractions In time-honoured tradition, the animals are out to grab as many sweets as they can throughout the festival. It’s up to the vigilant village guards to apprehend these pesky creatures! 1–4 Requires Wii U GamePad Number of required X to X Players No.