An Autoethnographical Tapestry of Feminist Reflection on My Journey of a Fitness Model Physique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bodybuilding and Fitness Doping in Transition. Historical Transformations and Contemporary Challenges

Article Bodybuilding and Fitness Doping in Transition. Historical Transformations and Contemporary Challenges Jesper Andreasson 1,* and Thomas Johansson 2 1 Department of Sport Science, Linnaeus University, 39182 Kalmar, Sweden 2 Department of Education, Learning and Communication, University of Gothenburg, 40530 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 16 January 2019; Accepted: 27 February 2019; Published: 4 March 2019 Abstract: This article describes and analyses the historical development of gym and fitness culture in general and doping use in this context in particular. Theoretically, the paper utilises the concept of subculture and explores how a subcultural response can be used analytically in relation to processes of cultural normalisation as well as marginalisation. The focus is on historical and symbolic negotiations that have occurred over time, between perceived expressions of extreme body cultures and sociocultural transformations in society—with a perspective on fitness doping in public discourse. Several distinct phases in the history of fitness doping are identified. First, there is an introductory phase in the mid-1950s, in which there is an optimism connected to modernity and thoughts about scientifically-engineered bodies. Secondly, in the 1960s and 70s, a distinct bodybuilding subculture is developed, cultivating previously unseen muscular male bodies. Thirdly, there is a critical phase in the 1980s and 90s, where drugs gradually become morally objectionable. The fourth phase, the fitness revolution, can be seen as a transformational phase in gym culture. The massive bodybuilding body is replaced with the well-defined and moderately muscular fitness body, but at the same time there are strong commercialised values which contribute to the development of a new doping market. -

The History of Bodybuilding: International and Hungarian Aspects

Művelődés-, Tudomány- és Orvostörténeti Folyóirat 2020. Vol. 10. No. 21. Journal of History of Culture, Science and Medicine e-ISSN: 2062-2597 DOI: 10.17107/KH.2020.21.165-178 The History of Bodybuilding: International and Hungarian Aspects A testépítés története: nemzetközi és magyar vonatkozások Petra Németh doctoral student dr. Andrea Gál docent Doctoral School of Sport Sciences, University of Physical Education [email protected], [email protected] Initially submitted Sept 2, 2020; accepted for publication Oct..20, 2020 Abstract Bodybuilding is a scarcely investigated cultural phenomenon in social sciences, and, in particular, historiography despite the fact that its popularity both in its competitive and leisure form has been on the rise, especially since the 1950s. Development periods of this sport are mainly identified with those iconic competitors, who were the most dominant in the given era, and held the ‘Mr. Olympia’ title as the best bodybuilders. Nevertheless, sources reflecting on the evolution of organizational background and the system of competitions are more difficult to identify. It is similarly challenging to investigate the history of female bodybuilding, which started in the 19th century, but its real beginning dates back to the 1970s. For analysing the history of international bodybuilding, mainly American sources can be relied on, but investigating the Hungarian aspects is hindered by the lack of background materials. Based on the available sources, the objective of this study is to discover the development -

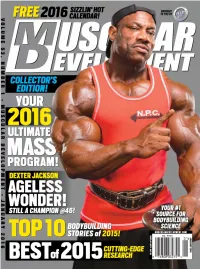

Muscular Development Is Your Number-One Source for Building Muscle, and for the Latest Research and Best Science to Enable You to Train Smart and Effectively

BONUS SIZE BONUS SIZE %MORE % MORE 20 FREE! 25 FREE! MUSCLETECH.COM MuscleTech® is America’s #1 Selling Bodybuilding Supplement Brand based on cumulative wholesale dollar sales 2001 to present. Facebook logo is owned by Facebook Inc. Read the entire label and follow directions. © 2015 NEW! PRO SERIES The latest innovation in superior performance from This complete, powerful performance line features the MuscleTech® is now available exclusively at Walmart! same clinically dosed key ingredients and premium The all-new Pro Series is a complete line of advanced quality you’ve come to trust from MuscleTech® over supplements to help you maximize your athletic the last 20 years. So you have the confi dence that potential with best-in-class products for every need: you’re getting the best research-based supplements NeuroCore®, an explosive, fast-acting pre-workout; possible – now at your neighborhood Superstore! CreaCore®, a clinically dosed creatine amplifier; MyoBuild®4X, a powerful amino BCAA recovery formula; AlphaTest®, a Clinically dosed, lab-tested key ingredients max-strength testosterone booster; and Muscle Builder, Formulated and developed based on the extremely powerful, clinically dosed musclebuilder. multiple university studies Plus, take advantage of the exclusive Bonus Size of Fully-disclosed formulas – no hidden blends our top-selling sustained-release protein – PHASE8TM. Instant mixing and amazing taste ERICA M ’S A # SELLING B Gŭŭ S OD IN UP YBUILD ND PLEMENT BRA BONUS SIZE MORE 33%FREE! EDITOR’s LETTER BY STEVE BLECHMAN, Publisher and Editor-in-Chief DEXTER JACKSON IS ‘THE BLADE’ BODYBUILDING’S NEXT GIFT? eing the number-one bodybuilder in the world is an achievement that commands respect from fans and fellow competitors alike. -

GMV Productions

GMV Productions Over 50 years of mail order and world-wide internet trading. WHAT SORT OF SERVICE CAN I EXPECT? You will receive the fastest, most friendly and courteous service, the equal of the very best web based mail order trader. As a general rule, all orders go the same day they are received. If you have a problem, email me personally at [email protected]<a target="_blank"></a> OUR GMV PRINCIPLES OF DOING BUSINESS The Guiding Principle. We believe in doing what's right for our customers. We will do whatever is necessary to satisfy your requests and fill your orders promptly. GMV Productions www.gmv.com.au has the largest collection of bodybuilding DVDs in the world featuring the top male and female bodybuilders and fitness athletes. GMV Bodybuilding www.gmvbodybuilding.com has one of the largest selections of male and female Digital Downloads of bodybuilders, contests and fitness athletes. All of our downloadable videos have been transferred directly from the original video master tapes and we are using the latest compression technology to produce high quality MP4 videos. We can say this because GMV Productions has been filming bodybuilding features, posing routines, events such as Olympias, Mr. Universe contests to natural amateur competitions, strongman, pump rooms, strength events, powerlifting and fitness expos - since 1965. In addition to the biggest range of titles, we also have the biggest names. These include, but are not restricted to names such as Arnold Schwarzenegger, Ronnie Coleman, Dorian Yates, Lee Haney, Jay Cutler, Sergio Oliva and all of the Olympia winners to present-day stars such as Phil Heath, Kai Greene, Dennis Wolf, Shawn Rhoden, Flex Lewis, Branch Warren etc amongst the men and every Ms Olympia winner, Iris Kyle, Cory Everson, Yaxeni Oriquen, Adela Garcia, Nicole Wilkins, Oksana Grishina, Alina Popa etc amongst the women. -

Origem E Desenvolvimento Do Fisiculturismo: Uma Análise Fílmica

Centro Universitário do Planalto Central Apparecido dos Santos Curso de Educação Física Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso Origem e Desenvolvimento do Fisiculturismo: uma análise fílmica Brasília-DF 2020 MARCELO VÍTOR BENÍCIO DE PINHO Origem e Desenvolvimento do Fisiculturismo: uma análise fílmica Artigo apresentado como requisito para conclusão do curso de Bacharelado em Educação Física pelo Centro Universitário do Planalto Central Apparecido dos Santos – Uniceplac. Orientador: Prof. Me. Demerson Godinho Maciel. Brasília-DF 2020 MARCELO VÍTOR BENÍCIO DE PINHO Origem e Desenvolvimento do Fisiculturismo: uma análise fílmica Artigo apresentado como requisito para conclusão do curso de Bacharelado em Educação Física pelo Centro Universitário do Planalto Central Apparecido dos Santos – Uniceplac. Brasília, 23 de novembro de 2020. Banca Examinadora Prof. Me. Demerson Godinho Maciel Orientador Prof. Dr. Arilson Fernandes Mendonça de Sousa Examinador Interno Prof. Me. Fernando Junio Antunes de Oliveira Cruz Examinador Externo 4 Origem e Desenvolvimento do Fisiculturismo: uma análise fílmica Marcelo Vítor Benício de Pinho1 Resumo: Este estudo buscou por meio de uma análise fílmica sobre o documentário Iron Generation 2, produzido no ano de 2017, sob a direção de Vlad Yudin, ampliar a visão acerca do fisiculturismo, por meio da análise de conteúdo das entrevistas de grandes personalidades do esporte, em que foi possível discorrer um pouco mais sobre a evolução do fisiculturismo, preconceito, uso de esteroides anabolizantes, questões psicológicas, entre outros temas, assim, o trabalho expõe de maneira mais ampla, um pouco da vida, rotina, pensamentos, e frustrações desses atletas que entregam suas vidas por esse esporte ainda tão desvalorizado no país. Palavras-chave: Corporeidade, Atletas, Fisiculturismo, Análise Fílmica. -

Pumping Iron Discussion Guide

www.influencefilmclub.com Pumping Iron Discussion Guide Directors: George Butler, Robert Fiore Year: 1977 Time: 85 min You might know this director from: Pumping Iron II: The Women (1985) The Endurance (2000) FILM SUMMARY Groundbreaking docudrama, PUMPING IRON, provides a compelling portrayal of the bodybuilding industry in the mid-1970. As the film’s central figures prepare themselves for the 1975 Mr. Olympia competition in Pretoria, South Africa, a spotlight is shined on this rather niche sport. World-famous, five-time Mr. Olympia champion, “the one and only Arnold Schwarzenegger” is at the forefront of the film. In defending his title, Schwarzenegger guides us through the ins and outs, ups and downs of this seemingly cosmetic sport which puts endurance and motivation to the test. Contestants compete in a tight-knit community, simultaneously supporting and taunting one another in a battle to be the best, to stand at the top of the number-one platform. In the end, it is the charm and ease of Schwarzenegger’s personality that wins us over, and we witness how the psychology of bodybuilding is just as important as physical training. Schwarzenegger baffles and belittles the competition as they sculpt their physiques to such highly developed states through endless hours of weight lifting, running, boxing, swimming, and bronzing. From Arnold’s training site of Gold’s Gym on the Californian coast to the competition venue in South Africa, from Franco Columbu’s hometown in Sardinia to Lou Ferrigno’s home in Brooklyn, New York, PUMPING IRON displays the oiled-up, hardened bodies of those men out on the hunt for corporeal perfection, and even helps launch a few acting careers in its wake. -

Pump&Circum Stance

RUTH SILVERMAN’S PUMP&CIRCUM STANCE Ms. O’s Fate Plus, fun in Santa Barbara The first Ms. Olympia competition I ever at- natural evolution, the huge Columbus, tended was in 1986, at the Felt Forum of Madi- Cory in ’88. Ohio, weekend is adding 212-and- son Square Garden in New York, the greatest under men’s bodybuilding as well as city in the world. Rick Wayne had just hired me men’s and women’s physique. to be his executive editor at Flex, and I was tak- As for the Ms. Olympia, promoter ing a crash course in the wacky world of weight Robin Chang hasn’t made any an- training. I knew very little about bodybuilding, nouncements, but based on all those particularly the women’s sport, but I was eager years of observation, I’d imagine that to learn, and, hey, any the organizers are still considering excuse to go to New what to do and that the contest may York for Thanksgiving be held somewhere near the end of weekend, the contest’s the season, in conjunction with anoth- date and destination for er event. Recall that in 1999, after that several years back then. year’s promoter could not pull it off Cory Everson was as a standing show, the late Kenny at the height of her six- Kassel and the still very alive Bob year reign. She was at- Bonham stepped up and added the tractive; had nice, round, Ms. O to the late-season show they athletic-looking muscle were putting on in New Jersey. -

Bodybuilding and Fitness Doping in Transition. Historical Transformations and Contemporary Challenges

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article Bodybuilding and Fitness Doping in Transition. Historical Transformations and Contemporary Challenges Jesper Andreasson 1,* and Thomas Johansson 2 1 Department of Sport Science, Linnaeus University, 39182 Kalmar, Sweden 2 Department of Education, Learning and Communication, University of Gothenburg, 40530 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 16 January 2019; Accepted: 27 February 2019; Published: 4 March 2019 Abstract: This article describes and analyses the historical development of gym and fitness culture in general and doping use in this context in particular. Theoretically, the paper utilises the concept of subculture and explores how a subcultural response can be used analytically in relation to processes of cultural normalisation as well as marginalisation. The focus is on historical and symbolic negotiations that have occurred over time, between perceived expressions of extreme body cultures and sociocultural transformations in society—with a perspective on fitness doping in public discourse. Several distinct phases in the history of fitness doping are identified. First, there is an introductory phase in the mid-1950s, in which there is an optimism connected to modernity and thoughts about scientifically-engineered bodies. Secondly, in the 1960s and 70s, a distinct bodybuilding subculture is developed, cultivating previously unseen muscular male bodies. Thirdly, there is a critical phase in the 1980s and 90s, where drugs gradually become morally objectionable. The fourth phase, the fitness revolution, can be seen as a transformational phase in gym culture. The massive bodybuilding body is replaced with the well-defined and moderately muscular fitness body, but at the same time there are strong commercialised values which contribute to the development of a new doping market. -

Not Simply Women's Bodybuilding: Gender and the Female Competition Categories

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Institute for Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Theses Studies Spring 5-1-2013 Not Simply Women's Bodybuilding: Gender and the Female Competition Categories Sheena A. Hunter Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/wsi_theses Recommended Citation Hunter, Sheena A., "Not Simply Women's Bodybuilding: Gender and the Female Competition Categories." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2013. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/wsi_theses/27 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOT SIMPLY WOMEN’S BODYBUILDING: GENDER AND THE FEMALE COMPETITION CATEGORIES by SHEENA A. HUNTER Under the Direction of Dr. Megan Sinnott ABSTRACT Once known only as Bodybuilding and Women’s Bodybuilding, the sport has grown to include multiple competition categories that both limit and expand opportunities for female bodybuilders. While the creation of additional categories, such as Fitness, Figure, Bikini, and Physique, appears to make the sport more inclusive to more variations and interpretation of the feminine, muscular physique, it also creates more in-between spaces. This auto ethnographic research explores the ways that multiple female competition categories within the sport of Bodybuilding define, reinforce, and complicate the gendered experiences of female physique athletes, by bringing freak theory into conversation with body categories. INDEX WORDS: Women’s bodybuilding, Gender performativity, Femininity, Gender, Freaks, Competition categories, In-betweenness, Stuckness NOT SIMPLY WOMEN’S BODYBUILDING: GENDER AND THE FEMALE COMPETITION CATEGORIES by SHEENA A. -

COMPETITIVE BODYBUILDERS and IDENTITY Insights from New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. COMPETITIVE BODYBUILDERS AND IDENTITY Insights from New Zealand A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Management, College of Business Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand. Anne Probert 2009 ABSTRACT This research explores competitive bodybuilders in New Zealand and their identities. Bodybuilders have often been construed as being broadly similar – excessively muscular people, who build their physiques for sometimes questionable reasons, such as for a cover for internal insecurities. Bodybuilding is often considered acceptable for men because muscles are symbolic of masculinity – on women they are seen as unnatural and unfeminine. While external critiques have tended to portray bodybuilders in a negative light, phenomenological accounts have often emphasised participants’ positive experiences. Existing research concerning the identity of bodybuilders has only scratched the surface. Identities reflect an understanding of ‘who one is’ – the continuing meanings people associate with themselves and as members of social groups. Furthermore, bodybuilders are not just ‘bodybuilders’, they are also people. Bodybuilding is not their only identity, it is one of their numerous identities. This research explored not only the meanings participants attribute to bodybuilding, but also how it is lived and experienced within the broader self. A phenomenological-inspired, mixed methodological approach was adopted using quantitative and qualitative methods. Participants were male and female competitive bodybuilders of varying ages residing in New Zealand. -

The Steve Wennerstrom Papers Part 2 Finding Aid Abstract Access

T h e Steve Wennerstrom Papers Part 2 The H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture & Sports The University of Texas at Austin Finding Aid Steve Wennerstrom Papers Part 2: 26 Boxes: 443 Folders, 2 Artifact and Media Boxes, 1 Large Photograph Box, 2 Trophies, no date, 1932-2017 (10755 items) Abstract Steve Wennerstrom is an expert on the history of women’s bodybuilding. He has served as the International Federation of Bodybuilding (IFBB) Women’s Historian. However, his interest in women’s sports extends beyond bodybuilding and the collection reflects that reality. Almost every sport that women have played is represented, making the Steve Wennerstrom Papers Part 2 an invaluable resource to all researchers with an interest in women’s sports. Wennerstrom graduated from Cal State Fullerton and ran track. He also created one of the first women’s track publications, Women’s Track and Field World. The collection covers everything from strongwomen and circus performers to bodybuilding and powerlifting. It is truly an amazing knowledge base for bodybuilding and sports fans everywhere, especially those interested in the rise of women’s sports throughout the recent decades. Access Access to the Steve Wennerstrom Papers Part 2 is restricted to visitors of the H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports and must be requested in writing prior to arrival at the Center. Furthermore, certain items in the collection (as identified below) are not suitable to be viewed by minors. The research request/proposal should explain the proposed project, the expected outcome, and institutional affiliation, if any.