The Fabrication of Medieval History: Archaeology and Artifice at the Office of Works Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LCA Introduction

The Hambleton and Howardian Hills CAN DO (Cultural and Natural Development Opportunity) Partnership The CAN DO Partnership is based around a common vision and shared aims to develop: An area of landscape, cultural heritage and biodiversity excellence benefiting the economic and social well-being of the communities who live within it. The organisations and agencies which make up the partnership have defined a geographical area which covers the south-west corner of the North York Moors National Park and the northern part of the Howardian Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The individual organisations recognise that by working together resources can be used more effectively, achieving greater value overall. The agencies involved in the CAN DO Partnership are – the North York Moors National Park Authority, the Howardian Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, English Heritage, Natural England, Forestry Commission, Environment Agency, Framework for Change, Government Office for Yorkshire and the Humber, Ryedale District Council and Hambleton District Council. The area was selected because of its natural and cultural heritage diversity which includes the highest concentration of ancient woodland in the region, a nationally important concentration of veteran trees, a range of other semi-natural habitats including some of the most biologically rich sites on Jurassic Limestone in the county, designed landscapes, nationally important ecclesiastical sites and a significant concentration of archaeological remains from the Neolithic to modern times. However, the area has experienced the loss of many landscape character features over the last fifty years including the conversion of land from moorland to arable and the extensive planting of conifers on ancient woodland sites. -

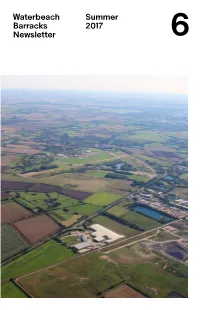

Waterbeach Barracks Newsletter Summer 2017

Waterbeach Summer Barracks 2017 Newsletter 6 Welcome to the sixth community newsletter from Urban&Civic. Urban&Civic is the Development Manager appointed by the Hello Defence Infrastructure Organisation (DIO) to take forward the development of the former Waterbeach Barracks and Airfield site. In this edition: With the Outline Planning Application submitted in February 2017, and formal consultation events Waterbeach Running Festival 4-5 concluded, the key partners involved are working through a range of follow-up discussions and Summer at the Beach 6-7 technical reviews as part of the planning process. 514 Squadron Reunion 8 While those discussions continue, Urban&Civic is continuing to open up the Barracks for local Planehunters Lancaster 9 use and is building local partnerships to ensure NN775 Excavation the development coming forward maximises local benefits and minimises local impacts. Reopening of the Waterbeach 10-11 Military Heritage Museum In this newsletter we set out the latest on the planning discussions and some of the recent Feature on Denny Abbey and 12-15 community events on site including the Waterbeach The Farmland Museum Running Festival, Summer at the Beach and the reopening of the Waterbeach Military Heritage Cycling Infrastructure 16-17 Museum. We have also been out and about exploring Denny Abbey and the Farmland Museum. Planning update 18-19 We are always happy to meet up with anyone who wants a more detailed discussion of the plans, to come along to speak to local groups or provide a tour of the site or the facilities for hire. Please get in touch with me using the contact details below. -

HERITAGE CYCLE TRAILS in North Yorkshire

HERITAGE CYCLE TRAILS Leaving Rievaulx Abbey, head back Route Two English Heritage in Yorkshire to the bridge, and turn right, in North Yorkshire continuing towards Scawton. Scarborough Castle-Whitby Abbey There’s always something to do After a few hundred metres, you’ll (Approx 43km / 27 miles) with English Heritage, whether it’s pass a turn toward Old Byland enjoying spectacular live action The route from Scarborough Castle to Whitby Abbey and Scawton. Continue past this, events or visiting stunning follows a portion of the Sustrans National Cycle and around the next corner, locations, there are over 30 Network (NCN route number one) which is well adjacent to Ashberry Farm, turn historic properties and ancient signposted. For more information please visit onto a bridle path (please give monuments to visit in Yorkshire www.sustrans.org.uk or purchase the official Sustrans way to horses), which takes you south, past Scawton Croft and alone. For details of opening map, as highlighted on the map key. over Scawton Moor, with its Red Deer Park. times, events and prices at English Heritage sites visit There are a number of options for following this route www.english-heritage.org.uk/yorkshire. For more The bridle path crosses the A170, continuing into the Byland between two of the North Yorkshire coast’s most iconic and information on cycling and sustainable transport in Yorkshire Moor Plantation at Wass Moor. The path eventually joins historic landmarks. The most popular version of the route visit www.sustrans.org.uk or Wass Bank Road, taking you down the steep incline of Wass takes you out of the coastal town of Scarborough. -

England | HIKING COAST to COAST LAKES, MOORS, and DALES | 10 DAYS June 26-July 5, 2021 September 11-20, 2021

England | HIKING COAST TO COAST LAKES, MOORS, AND DALES | 10 DAYS June 26-July 5, 2021 September 11-20, 2021 TRIP ITINERARY 1.800.941.8010 | www.boundlessjourneys.com How we deliver THE WORLD’S GREAT ADVENTURES A passion for travel. Simply put, we love to travel, and that Small groups. Although the camaraderie of a group of like- infectious spirit is woven into every one of our journeys. Our minded travelers often enhances the journey, there can be staff travels the globe searching out hidden-gem inns and too much of a good thing! We tread softly, and our average lodges, taste testing bistros, trattorias, and noodle stalls, group size is just 8–10 guests, allowing us access to and discovering the trails and plying the waterways of each opportunities that would be unthinkable with a larger group. remarkable destination. When we come home, we separate Flexibility to suit your travel style. We offer both wheat from chaff, creating memorable adventures that will scheduled, small-group departures and custom journeys so connect you with the very best qualities of each destination. that you can choose which works best for you. Not finding Unique, award-winning itineraries. Our flexible, hand- exactly what you are looking for? Let us customize a journey crafted journeys have received accolades from the to fulfill your travel dreams. world’s most revered travel publications. Beginning from Customer service that goes the extra mile. Having trouble our appreciation for the world’s most breathtaking and finding flights that work for you? Want to surprise your interesting destinations, we infuse our journeys with the traveling companion with a bottle of champagne at a tented elements of adventure and exploration that stimulate our camp in the Serengeti to celebrate an important milestone? souls and enliven our minds. -

Geoffrey Wheeler

Ricardian Bulletin Magazine of the Richard III Society ISSN 0308 4337 March 2012 Ricardian Bulletin March 2012 Contents 2 From the Chairman 3 Society News and Notices 9 Focus on the Visits Committee 14 For Richard and Anne: twin plaques (part 2), by Geoffrey Wheeler 16 Were you at Fotheringhay last December? 18 News and Reviews 25 Media Retrospective 27 The Man Himself: Richard‟s Religious Donations, by Lynda Pidgeon 31 A new adventure of Alianore Audley, by Brian Wainwright 35 Paper from the 2011 Study Weekend: John de la Pole, earl of Lincoln, by David Baldwin 38 The Maulden Boar Badge, by Rose Skuse 40 Katherine Courtenay: Plantagenet princess, Tudor countess (part 2), by Judith Ridley 43 Miracle at Denny Abbey, by Lesley Boatwright 46 Caveat emptor: some recent auction anomalies, by Geoffrey Wheeler 48 The problem of the gaps (from The Art of Biography, by Paul Murray Kendall) 49 The pitfalls of time travelling, by Toni Mount 51 Correspondence 55 The Barton Library 57 Future Society Events 59 Branches and Groups 63 New Members and Recently Deceased Members 64 Calendar Contributions Contributions are welcomed from all members. All contributions should be sent to Lesley Boatwright. Bulletin Press Dates 15 January for March issue; 15 April for June issue; 15 July for September issue; 15 October for December issue. Articles should be sent well in advance. Bulletin & Ricardian Back Numbers Back issues of The Ricardian and the Bulletin are available from Judith Ridley. If you are interested in obtaining any back numbers, please contact Mrs Ridley to establish whether she holds the issue(s) in which you are interested. -

ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain

ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain Volume 4.5:2002 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.40.219, on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:49:11, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0066622X00001118 SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS OF GREAT BRITAIN The Alice Davis Hitchcock Medallion is presented annually to authors of outstanding contributions to the literature of architectural history. Recipients of the award have been: 1959: H. M. COLVIN 1981: HOWARD COLVIN i960: JOHN SUMMERSON 1982: PETER THORNTON 1961: KERRY DOWNES 1983: MAURICE CRAIG 1962: JOHN FLEMING 1984: WILLIAM CURTIS 1963: DOROTHY STROUD 1985: JILL LEVER 1964: F. H. W. SHEPPARD 1986: DAVID BROWNLEE 1965: H. M. & JOAN TAYLOR 1987: JOHN HARVEY 1966: NIKOLAUS PEVSNER 1988: ROGER STALLEY 1967: MARK GIROUARD 1989: ANDREW SAINT 1968: CHRISTOPHER HUSSEY 1990: CHARLES SAUMAREZ SMITH 1969: PETER COLLINS 1991: CHRISTOPHER WILSON 1970: A. H. GOMME& 1992: EILEEN HARRIS & NICHOLAS SAVAGE D. M. WALKER 1993: JOHN ALLAN 1971: JOHN HARRIS 1994: COLIN CUNNINGHAM & 1972: HBRMIONE HOBHOUSE PRUDENCE WATERHOUSE 1973: MARK GIROUARD 1995: MILES GLENDINNING & 1974: J. MORDAUNT CROOK & STEFAN MUTHESIUS M. H. PORT 1996: ROBERT HILLENBRAND 1975: DAVID WATKIN 1997: ROBIN EVANS 1976: ANTHONY BLUNT 1998: IAN BRISTOW 1977: ANDREW SAINT 1999: DEREK LINSTRUM 1978: PETER SMITH 2000: LINDA FAIRBAIRN 1979: TED RUDDOCK 2001: NICHOLAS COOPER, PETER 1980: ALLAN BRAHAM FERGUSSON & STUART HARRISON 17K Society's Essay Medal is presented annually to the winner of the Society's essay medal competition. -

RIEVAULX ABBEY and ITS SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT, 1132-1300 Emilia

RIEVAULX ABBEY AND ITS SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT, 1132-1300 Emilia Maria JAMROZIAK Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2001 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Dr Wendy Childs for her continuous help and encouragement at all stages of my research. I would also like to thank other faculty members in the School of History, in particular Professor David Palliser and Dr Graham Loud for their advice. My thanks go also to Dr Mary Swan and students of the Centre for Medieval Studies who welcomed me to the thriving community of medievalists. I would like to thank the librarians and archivists in the Brotherton Library Leeds, Bodleian Library Oxford, British Library in London and Public Record Office in Kew for their assistance. Many people outside the University of Leeds discussed several aspects of Rievaulx abbey's history with me and I would like to thank particularly Dr Janet Burton, Dr David Crouch, Professor Marsha Dutton, Professor Peter Fergusson, Dr Brian Golding, Professor Nancy Partner, Dr Benjamin Thompson and Dr David Postles as well as numerous participants of the conferences at Leeds, Canterbury, Glasgow, Nottingham and Kalamazoo, who offered their ideas and suggestions. I would like to thank my friends, Gina Hill who kindly helped me with questions about English language, Philip Shaw who helped me to draw the maps and Jacek Wallusch who helped me to create the graphs and tables. -

Chapter 3: Strategic Sites

ChapterChapter 33 StrategicStrategic SitesSites Northstowe Bourn Airfield New Village Waterbeach New Town Cambourne West Proposed Submission South Cambridgeshire Local Plan July 2013 Chapter 3 Strategic Sites Chapter 3 Strategic Sites 3.1 The Spatial Strategy Chapter identifies the objectively assessed housing requirement for 19,000 new homes in the district over the period 2011-2031 and the strategic sites that form a major part of the development strategy in the Local Plan. These are a combination of sites carried forward from the Local Development Framework (2007-2010) and three new sites. Policy S/6 confirms that the Area Action Plans for the following sites remain part of the development plan for the plan period to 2031 or until such time as the developments are complete: Northstowe (except as amended by Policy SS/7 in this chapter) North West Cambridge; Cambridge Southern Fringe; and Cambridge East (except as amended by Policy SS/3 in this chapter). 3.2 This chapter includes polices for the following existing and new strategic allocations for housing, employment and mixed use developments: Edge of Cambridge: Orchard Park – site carried forward from the Site Specific Policies Development Plan Document (DPD) 2010 with updated policy to provide for the completion of the development; Land between Huntingdon Road and Histon Road – the site carried forward from the Site Specific Policies DPD 2010 but extended to the north following the Green Belt review informing the Local Plan. The notional capacity of the sites as extended is -

Tang WK & Kam Helen

Study Tour Report for the Medieval Germany, Belgium, France and England (Cathedral, Castle and Abbey --- a day visit in York) TANG Wai Keung / Helen KAM 1 Study Tour Report for the Medieval Germany, Belgium, France and England (Cathedral, Castle and Abbey --- a day visit in York) During this 8-day tour in England, we were requested to present a brief on York around its history, famous persons, attractive buildings and remarkable events etc. With the float of the same contents kept in minds even after the tour, we are prepared to write a study tour report based on this one-day visit with emphasis around its medieval period. York has a long turbulent period of history and, as King Edward VI said, “The history of York is the history of England”. This report will start with a brief history of York, which inevitably be related to persons, events and places we came across during this medieval tour. The report will also describe three attractions in York, viz., York Minster and its stained glass, Helmsley Castle and Rievaulx Abbey. 1 York's history The most important building in York is the York Minster, where in front of the main entrance, we found a statue of Constantine (photo 1). It reflects the height of Roman’s powers that conquered the Celtic tribes and founded Eboracum in this city; from here, the history of York started. 1.1 Roman York During our journey in the southern coast of England, Father Ha introduced to us the spots where the Roman first landed in Britain. -

Lilleshall Parish Council the Memorial Hall, Hillside, Lilleshall, Shropshire, TF10 9HG

J3/60/2 Lilleshall Parish Council The Memorial Hall, Hillside, Lilleshall, Shropshire, TF10 9HG. Tel: 01952 676379 Email: [email protected] Dear Sir EXAMINATION OF THE TELFORD AND WREKIN LOCAL PLAN 2011-2031 MATTERS, ISSUES & QUESTIONS PAPER Matter – 3 Question 3.2 Is the Local Plan’s settlement hierarchy and proposed distribution of development, particularly between the urban and rural areas, sufficiently justified? With reference to paragraph 28 of the Framework, is adequate provision made for development in rural settlements? I write on behalf of the Lilleshall Parish Council to confirm our support for the statement issued by the Parish & Town Council Group regarding Policy HO10 of the emerging Local Plan. We (the Parish Council) would like to supplement the statement by pointing out that the fundamental aspects of our rural communities are the built and natural environments which combine to provide the intrinsic quality of our landscape. This makes our rural communities what they are. It is therefore impossible to consider the distribution of sustainable development within the rural area, without consideration for the natural environment. The emerging Local Plan provides for sustainable development along with protection of our natural environment through the Policy HO10 in conjunction with the proposals included in Section 6 - Natural environment, where Policy NE7 - Strategic Landscapes is of particular importance. However, Question 6.2 of the Matters challenges the justification of Strategic Landscapes and their consistency with national policy in the Framework. We therefore wish to supplement the statement issued by Parish & Town Council Group with the following points for your consideration. The Lilleshall Parish Council supports the adoption of the Strategic Landscapes, and their purpose to protect the appearance and intrinsic quality of the designated areas. -

Old Houses Shrewsbury

Old H ou se s Sh rewsbu ry THEIR HISTORY AND ASSOCIATIONS . O R H . E F R EST , Val l e lu o . c Ca mdoc a nd S r n l d b H n S e . eve y C , “ ’ ‘ A uthor o the Fa una o Nor th W a les F a un a o S ho slz z re etc . f f ' f p , 1 1 9 1 . W S on m e e e . ilding , Li it d , Print rs , Shr wsbury P R E F A C E . LTHOUGH many books dealing with the history or 2 topography of Shrewsbury have appeared from time m work t o to ti e , no devoted the history of its old I houses has hitherto been published . n the present volume I h a ve tried to give a succinct a ccount of these in terestin g — ’ old buildings Shrewsbury s most a ttractive feature l a m partly by co lating all available dat regarding the , and partly by careful study and comparison of the structures themselves . The principal sources of information as to their past ’ history are Owen an d Bl akeway s monument a l History of S hrewsbur y , especially the numerous footnotes therein the Tra n sa ction s of the S hropshir e A r chwol ogica l S oc iety in clud ’ n d Bl k M S . a a ewa s ing the famous Taylor . y Topo ’ graphical History oi Shrewsbury Owen s A c coun t of S hrewsbury published an onymously in 1 80 8 S hropshir e Notes a n d Quer ies reprinted from the Shrewsbury Chr on i cle and S hr eds a n d P a tches a similar series of earlier ’ ’ date from Eddowes Journal . -

English Monks Suppression of the Monasteries

ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES by GEOFFREY BAS KER VILLE M.A. (I) JONA THAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED I937 JONATHAN CAPE LTD. JO BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON AND 91 WELLINGTON STREET WEST, TORONTO PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN IN THE CITY OF OXFORD AT THE ALDEN PRESS PAPER MADE BY JOHN DICKINSON & CO. LTD. BOUND BY A. W. BAIN & CO. LTD. CONTENTS PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 I MONASTIC DUTIES AND ACTIVITIES I 9 II LAY INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 45 III ECCLESIASTICAL INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 72 IV PRECEDENTS FOR SUPPRESSION I 308- I 534 96 V THE ROYAL VISITATION OF THE MONASTERIES 1535 120 VI SUPPRESSION OF THE SMALLER MONASTERIES AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE 1536-1537 144 VII FROM THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE TO THE FINAL SUPPRESSION 153 7- I 540 169 VIII NUNS 205 IX THE FRIARS 2 2 7 X THE FATE OF THE DISPOSSESSED RELIGIOUS 246 EPILOGUE 273 APPENDIX 293 INDEX 301 5 PREFACE THE four hundredth anniversary of the suppression of the English monasteries would seem a fit occasion on which to attempt a summary of the latest views on a thorny subject. This book cannot be expected to please everybody, and it makes no attempt to conciliate those who prefer sentiment to truth, or who allow their reading of historical events to be distorted by present-day controversies, whether ecclesiastical or political. In that respect it tries to live up to the dictum of Samuel Butler that 'he excels most who hits the golden mean most exactly in the middle'.