Once Upon a Time in Italy by Daniel Paris-Clavel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It 2.007 Vc Italian Films On

1 UW-Madison Learning Support Services Van Hise Hall - Room 274 rev. May 3, 2019 SET CALL NUMBER: IT 2.007 VC ITALIAN FILMS ON VIDEO, (Various distributors, 1986-1989) TYPE OF PROGRAM: Italian culture and civilization; Films DESCRIPTION: A series of classic Italian films either produced in Italy, directed by Italian directors, or on Italian subjects. Most are subtitled in English. Individual times are given for each videocassette. VIDEOTAPES ARE FOR RESERVE USE IN THE MEDIA LIBRARY ONLY -- Instructors may check them out for up to 24 hours for previewing purposes or to show them in class. See the Media Catalog for film series in other languages. AUDIENCE: Students of Italian, Italian literature, Italian film FORMAT: VHS; NTSC; DVD CONTENTS CALL NUMBER Il 7 e l’8 IT2.007.151 Italy. 90 min. DVD, requires region free player. In Italian. Ficarra & Picone. 8 1/2 IT2.007.013 1963. Italian with English subtitles. 138 min. B/W. VHS or DVD.Directed by Frederico Fellini, with Marcello Mastroianni. Fellini's semi- autobiographical masterpiece. Portrayal of a film director during the course of making a film and finding himself trapped by his fears and insecurities. 1900 (Novocento) IT2.007.131 1977. Italy. DVD. In Italian w/English subtitles. 315 min. Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci. With Robert De niro, Gerard Depardieu, Burt Lancaster and Donald Sutherland. Epic about friendship and war in Italy. Accattone IT2.007.053 Italy. 1961. Italian with English subtitles. 100 min. B/W. VHS or DVD. Directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini. Pasolini's first feature film. In the slums of Rome, Accattone "The Sponger" lives off the earnings of a prostitute. -

Three Leading Italian Film-Makers Have Been Invited by the Museum of Modern Art

m The Museum of Modern Art No. 50 FOR RELEASE: U West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 245-3200 Cable: Modernart Tuesday, April 8, I969 Three leading Italian film-makers have been invited by The Museum of Modern Art to address the American public, Willard Van Dyke, Director of the Department of Film, announced today. The directors are Bernardo Bertolucci, who will appear, 8:00 p.m., April 8th; Cesare Zavattini,scheduled to speak on May I3; and Marco Bellocchio,who will talk on June 10; specially chosen motion pictures will accompany the talks held in cooperation with the Istituto Italiano di Cultura. Programs start at 8:00 p.m. in the Museum Auditorium. The evening with Bernardo Bertolucci will include a preview of his most recent feature, "Partner" inspired by Dostoevski's "The Double." The picture,described by Bertolucci as "the story of a man who meets his own double," stars Pierre Clementi, who played the vile, sold-toothed anti-hero in "Belle de Jour." Bertolucci, a poet, at 22 made his second feature film "Before the Revolution," which received critical acclaim and created controversy. One critic, Roger Greenspun, wrote -- "the film draws directly upon Stendhal's 'Charter House of Parma;' in its mood and tone it draws perhaps as significantly upon Flaubert's 'Sentimental Education.' But in its meaning and in its particular kind of appreciation of all the life it observes, the picture stands by itself drawing essentially upon the sensibility and gift for under standing of the man who made it." The title, "Before the Revolution," derives from Talleyrand -- "only those who lived before the revolution knew how sweet life can be." The theme, reputedly auto biographical, deals with a young man's search to find his own values and discard the established ones of his respectable milieu. -

Mafia Motifs in Andrea Camilleri's Detective

MAFIA MOTIFS IN ANDREA CAMILLERI’S DETECTIVE MONTALBANO NOVELS: FROM THE CULTURE AND BREAKDOWN OF OMERTÀ TO MAFIA AS A SCAPEGOAT FOR THE FAILURE OF STATE Adriana Nicole Cerami A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures (Italian). Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Dino S. Cervigni Amy Chambless Roberto Dainotto Federico Luisetti Ennio I. Rao © 2015 Adriana Nicole Cerami ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Adriana Nicole Cerami: Mafia Motifs in Andrea Camilleri’s Detective Montalbano Novels: From the Culture and Breakdown of Omertà to Mafia as a Scapegoat for the Failure of State (Under the direction of Ennio I. Rao) Twenty out of twenty-six of Andrea Camilleri’s detective Montalbano novels feature three motifs related to the mafia. First, although the mafia is not necessarily the main subject of the narratives, mafioso behavior and communication are present in all novels through both mafia and non-mafia-affiliated characters and dialogue. Second, within the narratives there is a distinction between the old and the new generations of the mafia, and a preference for the old mafia ways. Last, the mafia is illustrated as the usual suspect in everyday crime, consequentially diverting attention and accountability away from government authorities. Few critics have focused on Camilleri’s representations of the mafia and their literary significance in mafia and detective fiction. The purpose of the present study is to cast light on these three motifs through a close reading and analysis of the detective Montalbano novels, lending a new twist to the genre of detective fiction. -

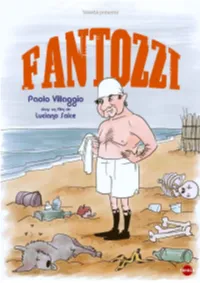

Ce N'est Pas À Moi De Dire Que Fantozzi Est L'une Des Figures Les Plus

TAMASA présente FANTOZZI un film de Luciano Salce en salles le 21 juillet 2021 version restaurée u Distribution TAMASA 5 rue de Charonne - 75011 Paris [email protected] - T. 01 43 59 01 01 www.tamasa-cinema.com u Relations Presse Frédérique Giezendanner [email protected] - 06 10 37 16 00 Fantozzi est un employé de bureau basique et stoïque. Il est en proie à un monde de difficultés qu’il ne surmonte jamais malgré tous ses efforts. " Paolo Villaggio a été le plus grand clown de sa génération. Un clown immense. Et les clowns sont comme les grands poètes : ils sont rarissimes. […] N’oublions pas qu’avant lui, nous avions des masques régionaux comme Pulcinella ou Pantalone. Avec Fantozzi, il a véritablement inventé le premier grand masque national. Quelque chose d’éternel. Il nous a humiliés à travers Ugo Fantozzi, et corrigés. Corrigés et humiliés, il y a là quelque chose de vraiment noble, n’est-ce pas ? Quelque chose qui rend noble. Quand les gens ne sont plus capables de se rendre compte de leur nullité, de leur misère ou de leurs folies, c’est alors que les grands clowns apparaissent ou les grands comiques, comme Paolo Villaggio. " Roberto Benigni " Ce n’est pas à moi de dire que Fantozzi est l’une des figures les plus importantes de l’histoire culturelle italienne mais il convient de souligner comment il dénonce avec humour, sans tomber dans la farce, la situation de l’employé italien moyen, avec des inquiétudes et des aspirations relatives, dans une société dépourvue de solidarité, de communication et de compassion. -

National Gallery of Art Fall 2014 Film Program

Film Fall 2014 Film Fall 2014 National Gallery of Art with American University School of Communication American Film Institute Goethe-Institut, Washington National Archives National Portrait Gallery Introduction 5 Schedule 7 Special Events 11 Suso Cecchi d’Amico: Homage at 100 15 Viewing China 19 American Originals Now: Jodie Mack 22 Morality and Beauty: Marco Bellocchio 23 The Play’s the Thing: Václav Havel, Art and Politics 28 Also Like Life: Hou Hsiao-hsien 30 Athens Today 32 Index 36 Standing Aside, Watching p34 Cover: Moon Over Home Village p19 During the fall of 2014, with the ongoing renovations in the East Building, a number of National Gallery of Art screen- ings are moving to various sites in Washington, DC; please note the temporary locations on the following pages. We are grateful this season for the cooperation of many other institutions, including the National Portrait Gallery, National Archives, American University, Goethe-Institut Washington, and American Film Institute. The season opens with a tribute to the influential Italian screenwriter Suso Cecchi d’Amico on her one-hundredth birthday. During subsequent weeks there are other opportunities to view the rich legacy of Italian cin- ema, including a retrospective devoted to Marco Bellocchio. Viewing China, a program of non-fiction work from mainland China, relates aspects of rural and urban life and contrasts recent indie cinema with films made by the state-owned Cen- tral Newsreel and Documentary Studio. In December there is an opportunity to view the important oeuvre of Taiwanese filmmaker Hou Hsiao-hsien during a major retrospective tak- ing place at the Freer Gallery, the American Film Institute, and the Goethe-Institut, in partnership with the National Gallery of Art. -

The Myth of the Good Italian in the Italian Cinema

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 5 No 16 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy July 2014 The Myth of the Good Italian in the Italian Cinema Sanja Bogojević Faculty of Philosophy, University of Montenegro Doi:10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n16p675 Abstract In this paper we analyze the phenomenon called the “myth of the good Italian” in the Italian cinema, especially in the first three decades of after-war period. Thanks to the recent success of films such as Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds or Academy Award- winning Benigni’s film La vita è bella and Spielberg’s Schindler’s List it is commonly believed that the Holocaust is a very frequent and popular theme. Nevertheless, this statement is only partly true, especially when it comes to Italian cinema. Soon after the atrocities of the WWII Italian cinema became one of the most prominent and influential thanks to its national film movement, neorealism, characterized by stories set amongst the poor and famished postwar Italy, celebrating the fight for freedom under the banners of Resistance and representing a nation opposed to the Fascist and Nazi regime. Interestingly, these films, in spite of their very important social engagement, didn’t even mention the Holocaust or its victims and it wasn’t until the 1960’s that Italian cinema focused on representing and telling this horrific stories. Nevertheless, these films represented Italians as innocent and incapable of committing cruel acts. The responsibility is usually transferred to the Germans as typically cold and sadistic, absolving Italians of their individual and national guilt. -

Film Schedule

Spaghetti Westerns - Week 1 – January 5 Week 6 – February 8 Winter 2017 Course Intro: Identifying The Zapata Spaghetti Plot Genres Run Man, Run (Corri uomo corri) – Professor: Yuri M. Sangalli Sergio Sollima, 1968 Week 2 – January 11 ☎: 661.2111 ext. 86039 The Classic Western Week 7 – February 15 ✉: Please use OWL for all course Shane – George Stevens, 1958 The (Stylized) Italian Western correspondence and (Genre) History Once Upon a Time in the West (C’era Marking scheme: una volta il West) – S. Leone, 1968 Test - two hours, in class 15% Group presentation + report February 20-24 Reading Week (written/web-based) 15% Essay - 2500 words max. 25% Final exam – three hours 30% Class participation and attendance* 15% Week 9 – March 8 *attendance taken at each After the Italian Western: The screening and class Professional Plot The Wild Bunch – Sam Peckinpah, Students are expected to view 1969 films and complete readings Week 10 – March 15 before coming to class. Vengeance Plots and Urban Week 3 – January 18 Vigilantes: the Poliziesco The Samurai Film and the Revolver – Sergio Sollima, 1973 Peplum Adventure Film Yojimbo – Akira Kurosawa, 1961 Week 11 – March 22 Quentin Tarantino’s “Southern Week 4 – January 25 Western” The Servant of 2 Masters Plot Week 8 – March 1 Django Unchained – Quentin Django – Sergio Corbucci, 1966 The Meta Spaghetti Western: Tarantino, 2012 Genre Parody Week 12 – March 29 Week 5 – February 1 My Name Is Nobody (Il mio nome è Group presentations The Transitional Plot nessuno) – Tonino Valerii, 1973 The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Il Week 13 – April 5 buono, il brutto e il cattivo) – Sergio March 2 – Test (2 hours) Group presentations Leone, 1966 Friday April 7 - Essay due . -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Uw Cinematheque Announces Fall 2012 Screening Calendar

CINEMATHEQUE PRESS RELEASE -- FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AUGUST 16, 2012 UW CINEMATHEQUE ANNOUNCES FALL 2012 SCREENING CALENDAR PACKED LINEUP INCLUDES ANTI-WESTERNS, ITALIAN CLASSICS, PRESTON STURGES SCREENPLAYS, FILMS DIRECTED BY ALEXSEI GUERMAN, KENJI MISUMI, & CHARLES CHAPLIN AND MORE Hot on the heels of our enormously popular summer offerings, the UW Cinematheque is back with the most jam-packed season of screenings ever offered for the fall. Director and cinephile Peter Bogdanovich (who almost made an early version of Lonesome Dove during the era of the revisionist Western) writes that “There are no ‘old’ movies—only movies you have already seen and ones you haven't.” With all that in mind, our Fall 2012 selections presented at 4070 Vilas Hall, the Chazen Museum of Art, and the Marquee Theater at Union South offer a moveable feast of outstanding international movies from the silent era to the present, some you may have seen and some you probably haven’t. Retrospective series include five classic “Anti-Westerns” from the late 1960s and early 70s; the complete features of Russian master Aleksei Guerman; action epics and contemplative dramas from Japanese filmmaker Kenji Misumi; a breathtaking survey of Italian Masterworks from the neorealist era to the early 1970s; Depression Era comedies and dramas with scripts by the renowned Preston Sturges; and three silent comedy classics directed by and starring Charles Chaplin. Other Special Presentations include a screening of Yasujiro Ozu’s Dragnet Girl with live piano accompaniment and an in-person visit from veteran film and television director Tim Hunter, who will present one of his favorite films, Tsui Hark’s Shanghai Blues and a screening of his own acclaimed youth film, River’s Edge. -

Appel À Contribution Édito Appel À Archive

ÉDITO Lettre envoyée par le président de l’association Home Cinéma à toutes les salles de cinéma parisiennes et aux institutions culturelles françaises , ou par mail à Bonjour, Depuis septembre 2019, l’association Home Cinéma que je préside occupe le cinéma [email protected] La Clef pour en empêcher la fermeture. Vous savez toutes et tous, comme moi, l’importance de cette salle et combien elle ne menace aucunement l’écosystème du paysage cinématographique français. Bien au contraire, elle complémente la production dominante sans lui porter préjudice, sans APPEL À ARCHIVE d'un numéro spécial, vue de la préparation En nous sommes à la recherche de tout document ou ou témoignages (photographies d'archives depuis sa du cinéma La Clef sur l'histoire autres) création. par courrier au nous les adresser pouvez Vous 34, rue Daubenton, 75005 Paris suivante : l'adresse de nous préciser leur n'oubliez pas P.S. : auteur•rice•s. et/ou provenance compétition déloyale. Ce cinéma a toujours accueilli des films précarisés et/ou laissé leur chance et du temps à des œuvres que les autres salles ne pouvaient plus garder sur leurs écrans. Nous savons votre soutien et vous en remercions. Mais aujourd’hui, il est urgent The Musketeers of Pig Alley, David Wark Griffith, 1912 que vous fassiez un pas supplémentaire pour prendre part à cette lutte. Son issue ne dépend plus de nous, l’association Home Cinéma, mais bien de vous, et de notre capacité à nous fédérer. La menace que constitue le groupe SOS concerne l’ensemble du secteur culturel parisien et français, et nous devons, collectivement, prendre la mesure de ce que cela signifie. -

(A) REGISTA TITOLO FILM QUANTITÀ Una

Fondo fotografico Ugo Casiraghi Scatola n. 10 ITALIA CONSUMO (A) INVENTARIO 197.592 QUANTITÀ FOTOGRAFIE: 136 REGISTA TITOLO FILM QUANTITÀ Duccio Tessari Una farfalla con le ali insanguinate 7 " " 1 Ignazio Dolce L'ammazzatina 2 " " 4 " " 2 " " 4 " " 1 " " 1 " " 1 n.r. " 1 n.r. " 1 n.r. " 15 n.r. n.r. 13 n.r. Banana Joe 2 n.r. Il giono del cobra 1 n.r. " 1 n.r. Sfrattato cerca casa equo canone 3 Luigi Filippo D'Amico L'arbitro 2 " " 1 " " 1 n.r. Frou Frou del Tabarin 2 Armando Crispino L'Etrusco uccide ancora 3 " " 1 " " 1 " " 1 " " 5 n.r. Quel movimento che mi piace tanto 5 n.r. Vamos a matar, compañeos 2 n.r. " 2 Franco Prosperi Un uomo dalla pelle dura 1 " " 1 " " 1 n.r. Processo per direttissima 3 Duccio Tessari Viva la muerte…tua! 1 " " 1 " " 1 Fernando Di Leo La bestia dagli occhi freddi 1 Pagina 1 Fondo fotografico Ugo Casiraghi Lucio Fulci I guerrieri dell'anno 2072 2 " " 1 n.r. Bello mio, bellezza mia 2 Silvio Amadio Quell'età maliziosa 4 " " 2 n.r. " 1 Franco Ferrini Caramelle da uno sconosciuto 1 Amico, stammi lontano almeno un Michele Lupo palmo… 1 " " 1 " " 4 Lucio Fulci Zanna bianca 1 Fausto Tozzi Trastevere 1 Giuseppe Murgia Maladolescenza 1 n.r. " 1 Luciano Salce La pecora nera 1 Duccio Tessari Tony Arzenta 1 Sergio Leone Il mio nome è Nessuno 1 n.r. " 1 n.r. " 1 Sergio Leone, Tonino Valerii " 1 " " 1 Giacomo Battiato Stradivari 1 Alberto Cavallone Zelda 5 Gianfranco Parolini Sotto a chi tocca 1 Luigi Faccini Garofano rosso 2 Pupi Avati Dichiarazione d'amore 1 ITALIA CONSUMO (B) INVENTARIO 197.594 QUANTITÀ FOTOGRAFIE: 141 REGISTA TITOLO FILM QUANTITÀ n.r. -

Roberto Rossellinips Rome Open City

P1: JPJ/FFX P2: FCH/FFX QC: FCH/FFX T1: FCH CB673-FM CB673-Gottlieb-v1 February 10, 2004 18:6 Roberto Rossellini’s Rome Open City Edited by SIDNEY GOTTLIEB Sacred Heart University, Fairfield, Connecticut v P1: JPJ/FFX P2: FCH/FFX QC: FCH/FFX T1: FCH CB673-FM CB673-Gottlieb-v1 February 10, 2004 18:6 PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press 2004 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2004 Printed in the United States of America Typefaces Stone Serif 9.5/13.5 pt. and Gill Sans System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, open city / edited by Sidney Gottlieb. p. cm. – (Cambridge film handbooks) Filmography: Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-521-83664-6 (hard) – ISBN 0-521-54519-6 (pbk.) 1. Roma, citta´ aperta (Motion picture) I. Gottlieb, Sidney. II. Cambridge film handbooks series. PN1997.R657R63