Alfred Stieglitz: Photographic Processes and Related Conservation Issue Author(S): Rachel Danzing Topics in Photographic Preservation, Volume 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Street—Design for a Poster

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Alfred Stieglitz Key Set Alfred Stieglitz (editor/publisher) after Various Artists Alfred Stieglitz American, 1864 - 1946 The Street—Design for a Poster 1900/1901, printed 1903 photogravure image: 17.6 × 13.2 cm (6 15/16 × 5 3/16 in.) Alfred Stieglitz Collection 1949.3.1270.34 Key Set Number 266 Image courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art KEY SET ENTRY Related Key Set Photographs The Street—Design for a Poster 1 © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Alfred Stieglitz Key Set Alfred Stieglitz Alfred Stieglitz The Street, Fifth Avenue Fifth Avenue—30th Street 1900/1901, printed 1903/1904 1900/1901, printed 1929/1937 photogravure gelatin silver print Key Set Number 267 Key Set Number 268 same negative same negative Remarks The date is based on stylistic similarities to Spring Showers—The Street Cleaner (Key Set number 269) and Spring Showers—The Coach (Camera Notes 5:3 [January 1902], pl. A). This photograph was made at Fifth Avenue and 30th Street with a Bausch & Lomb Extra Rapid Universal lens, and won a grand prize of $300 in the 1903 “Bausch & Lomb Quarter-Century Competition”(see Camera Work 5 [January 1904], 53; and The American Amateur Photographer 16 [February 1904], 92). Lifetime Exhibitions A print from the same negative—perhaps a photograph from the Gallery’s collection—appeared in the following exhibition(s) during Alfred Stieglitz’s lifetime: 1903, Hamburg (no. 424, as The Street, photogravure) 1903, San Francisco (no. 34a, as The Street—Winter) 1904, Washington (no. -

SP18 Experimental Photography AS

Studio Art Course Santa Reparata International School of Art Course Syllabus Semester: Spring 2018 Course Title: Experimental Photography Course Number: Art 315 Credits: 3, Contact Hours: 90 1. COURSE DESCRIPTION Designed for students who show evidence of a strong foundation in black and white dark- room practices. The course will examine a variety of techniques that include Polaroid trans- fer, Cyanotypes, Tonning, Liquid emulsion and Digital painting. Students will experiment with image manipulation on different supports including 3-D. Class time will include visits to mu- seums, field trips, technical demonstrations, darkroom work, individual and group critiques. 2. CONTENT INTRODUCTION Designed for advanced independent students wishing to add the element of experimentation to their work in photography. This course is designed to expand the student’s photographic vocabulary, to encourage experimentation, utilizing a variety of materials and techniques, and push the boundaries of what makes a photograph. In technical terms the class will be concentrated primarily with the experimentation of alter- native techniques and the development of a personal portfolio. Class time will include slide presentations on work by a wide variety of photographers, past and present, to help clarify project goals and possible approaches as well as to inspire students in their own work. During class time there will be technical demonstrations, critiques and photo-shooting field trips. 3. PREREQUISITES Black & White Photography II or equivalent. All students must have a SLR camera that permits manual adjustment of shutter speeds and apertures. All students are required to purchase photographic paper. It is recommended to bring all lenses, tripods and other equipment that belongs to your camera. -

The Platinum Print: a Catalyst for Discussion

The Platinum Print: a catalyst for discussion Defined: distinguished by its matte finish and subtle tonal gradations image is embedded into the fibers of the paper non-silver process iron salts are used to sensitize paper prior to development Upon exposure to light, a faint image appears development process converts iron salts platinum faint image becomes more pronounced1 1. The History of the Platinum Print Due to the similar qualities and processes, The terms platinotype, palladium prints and platinum prints are often used interchangeably. According to James Reilly, the platinotype and the platinum print are in fact congruent photographic processes yielding in what would be the same photographic print. Having said that please refer to figure 1.1, below. This chart demonstrates not necessarily the date of invention or discovery of the most popular historic photographic processes, but rather the years in which the process was most dominantly used. 1 Figure 1.1 Chronology of the use of photographic processes in the United States. (up to 1984.) The chart indicates that platinum prints were popular for approximately 40 years from 1870s to the 1930s, competing with the well-established albumen prints and eventually being overtaken by the gelatin silver processes which came on the scene about the same time. A long string of inventors and their inventions led to the ultimate culmination in what became known as the platinum print, one of the few non-silver processes used in photography. In 1830, Ferdinand Gehlen noted that ultraviolet light would alter the color of platinum salts and cause the ferric salts to separate out into a ferrous state. -

The Fascination of Flash Photography

The fascination of flash photography. 2016 / 2017 The fascination of flash photography “Paint” with the flash. Every subject has its own particular charm. The creative use of flash opens up numerous photographing possibilities, e.g. reducing the subject contrast, highlighting certain picture areas or getting rid of unwanted shadows. The first-class flash units from Metz offer natural colours and harmonious mood lighting – with every subject. Metz – always first class.. www.metz-mecatech.de picture: Geissler Dominik 2 — 3 Contents | A focus on quality 05 Tradition with a focus on the future 24 Every detail absolutely brilliant Contents 06 Your subject in the best 28 accessories possible light 32 Technical glossary 10 A lot of power for the best light 34 Technical specifications System flash units mecablitz mecablitz mecablitz 12 64 AF-1 digital 14 52 AF-1 digital 16 44 AF-2 digital mecablitz mecablitz mecablitz 18 M400 20 26 AF-2 22 36 AF-5 digital System flash units Specialist flash units mecablitz 18 M400 mecablitz mecablitz 23 24 AF-1 digital 26 15 MS-1 digital-Kit picture on title: Florian Gerlach Metz – always first class. www.metz-mecatech.de Metz mecatech – a focus on quality. The name Metz has been synonymous with professional flash units for decades. Our company’s exceptional reputation has been shaped by numerous technical innovations – such as the use of USB connections which allow flash units within the camera system to be updated for the latest camera model even after purchase. Today, we offer a diverse range of products from Whether light output, convenience of use or reliability, the convenient compact flashes right through to powerful handheld first-class quality of Metz flash units is unquestionable – as flash guns. -

The Platinum/Palladium Process

9 The Platinum/Palladium Process OVERVIEW AND EXPECTATIONS In the majority of the classes and workshops that I’ve taught over the years, “the platinum/palladium process” is the answer that surfaces first when I ask the question, “What process do you want to learn the most?” In this chapter you will learn how, and, as in previous chapters, I begin with a little history. Then you will learn the chemistry and sequence of the various stages to a finished print. This chapter gives you alternatives to traditional platinum/palladium chemistry and provides you with a simple sensitizer “drop chart” that is based on the type of negative you are working with, rather than the print you would like to make. I also provide the beginnings of a trouble-shooting list to assist in hunting down problems that may be showing up in your work. Finally, you’ll get some brief alternative ideas for combining platinum/palladium with other techniques such as Van Dyke and gum bichromate. A LITTLE HISTORY Like most refined non-silver and alternative photographic processes, the art of platinum/palladium printing was developed in pieces over time by a number of dedicated artists and scientists. In 1830, Ferdinand Gehlen recorded the action and effects of light on platinum chloride, noting that UV light would alter the color of platinum salts and cause the ferric salts to precipitate out into a ferrous state. At around the same time, Johann Wolfgang Dobereiner (1780–1849) observed the decomposition of ferric oxalate on exposure to UV light and scientifically defined its sensitivity. -

Master Professional Portrait Lighting with These 20 Essential Studio Setups

LIGHTING GUIDE Master professional portrait lighting with these 20 essential studio setups REMBRANDT WITH A PORTALITE SOFTBOX REMBRANDT THROUGH AN UMBRELLA REMBRANDT WITH A HONEYCOMB GRID REMBRANDT WITH A SILVER UMBRELLA KIT: One D-lite RX4 head, one Clip-lock KIT: One D-lite RX4 head, KIT: One D-lite RX4 head, KIT: One D-lite RX4 head, Stand, one Portalite Softbox one Clip-lock Stand, one 16cm Reflector, one Clip-lock Stand, one 18cm Reflector one Clip-lock Stand, one 16cm Reflector, Position the light high and to the side to one Shoot-through Umbrella with Honeycomb one Silver Umbrella create a triangle on the model’s cheek. The Position the light high and to the side as with Position the light in the same manner as the Position the light in the same manner as the shadow of the nose should point towards the the ‘Rembrandt with a Portalite Softbox’ previous ‘Rembrandt’ techniques; the light previous ‘Rembrandt’ techniques. The light edge of the lips. The Portalite creates a soft setup. The light is slightly less contrasty, through the honeycomb grid is stronger and bouncing from the silver umbrella is more directional effect. because the light is less directional more dramatic. The grid makes it very easy direct and wraps around the features of the and there is always some reflection to direct the light on to the model and away face yet still creates the shadow from the from the studio surroundings. from the background, which becomes dark. nose towards the mouth. REMBRANDT SHORT REMBRANDT BROAD SPLIT SPLIT WITH FILL KIT: One D-lite RX4 head, one Clip-lock KIT: One D-lite RX4 head, one Clip-lock KIT: One D-lite RX4 head, one Clip-lock KIT: One D-lite RX4 head, one Clip-lock Stand, one Portalite Softbox Stand, one Portalite Softbox Stand, one Portalite Softbox Stand, one Portalite Softbox, one Use the principles of ‘Rembrandt’ lighting Use the principles of ‘Rembrandt’ lighting Position a light to one side of the model in small reflector to create the triangle of light on the face. -

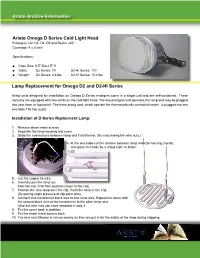

Lamp Replacement for Omega D2 and D2-HI Series Aristo Archive

Aristo Archive Information Aristo Omega D Series Cold Light Head Enlargers: D2, D3. D4, D5 and Besler 4x5* Coverage: 4 x 5 inch Specifications: ■ Case Size: 6.5” Dia x 5” H ■ Watts: D2 Series: 70 D2-HI Series: 110 ■ Weight: D2 Series: 4.8 lbs D2-HI Series: 15.4 lbs Lamp Replacement for Omega D2 and D2-HI Series Aristo units designed for installation on Omega D Series enlargers come in a single unit and are self-contained. These normally are equipped with two cords on the cold light head. The two pronged cord operates the lamp and may be plugged into your timer or footswitch. The three prong cord, which operate the thermostatically controlled heater, is plugged into any available 115 Vac outlet. Installation of D Series Replacment Lamp: 1. Remove sheet metal screws 2. Separate the lamp housing and cover 3. Undo the connections between lamp and Transformer. (By unscrewing the wire nuts.) 4. At the electrode-cut the silicone between lamp reflector housing (metal) and glass electrode by a sharp knife or blade. 5. Cut the copper tie wire. 6. Carefully pull the lamp out from the clip. (Pull from position closer to the clip) 7. Position the new lamp over the clip. Push the lamp in the Clip. (By putting slight pressure at clip point only) 8. Connect one transformer black wire to one lamp wire. Repeat the same with the second black wire of the transformer to the other lamp wire. (Use the wire nuts you have removed in step 3 8. Put the cover back in position. -

US Army Photography Course Laboratory Procedures SS0509

SUBCOURSE EDITION SS0509 8 LABORATORY PROCEDURES US ARMY STILL PHOTOGRAPHIC SPECIALIST MOS 84B SKILL LEVEL 1 AUTHORSHIP RESPONSIBILITY: SSG Dennis L. Foster 560th Signal Battalion Visual Information/Calibration Training Development Division Lowry AFB, Colorado LABORATORY PROCEDURES SUBCOURSE NO. SS0509-8 (Developmental Date: 30 June 1988) US Army Signal Center and Fort Gordon Fort Gordon, Georgia Five Credit Hours GENERAL The laboratory procedures subcourse is designed to teach tasks related to work in a photographic laboratory. Information is provided on the types and uses of chemistry, procedures for processing negatives and prints, and for mixing and storing chemicals, procedures for producing contact and projection prints, and photographic quality control. This subcourse is divided into three lessons with each lesson corresponding to a terminal learning objective as indicated below. Lesson 1: PREPARATION OF PHOTOGRAPHIC CHEMISTRY TASK: Determine the types and uses of chemistry, for both black and white and color, the procedures for processing negatives and prints, the procedures for mixing and storing chemicals. CONDITIONS: Given information and diagrams on the types of chemistry and procedures for mixing and storage. STANDARDS: Demonstrate competency of the task skills and knowledge by correctly responding to at least 75% of the multiple-choice test covering preparation of photographic chemistry. (This objective supports SM tasks 113-578-3022, Mix Photographic Chemistry; 113-578-3023, Process Black and White Film Manually; 113-578-3024, Dry Negatives in Photographic Film Drier; 113-578-3026, Process Black and White Photographic Paper). i Lesson 2: PRODUCE A PHOTOGRAPHIC PRINT TASK: Perform the procedures for producing an acceptable contact and projection print. -

Direct PDF Link for Archiving

Kurt E. Rahmlow “The admiration one feels for something strange and uncanny”: Impressionism, Symbolism, and Edward Steichen’s Submissions to the 1905 London Photographic Salon Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 15, no. 1 (Spring 2016) Citation: Kurt E. Rahmlow, “‘The admiration one feels for something strange and uncanny’: Impressionism, Symbolism, and Edward Steichen’s Submissions to the 1905 London Photographic Salon,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 15, no. 1 (Spring 2016), http://www. 19thc-artworldwide.org/spring16/rahmlow-on-impressionism-symbolism-steichen-1905- london-photographic-salon. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Rahmlow: Impressionism, Symbolism, and Edward Steichen’s Submissions to the 1905 London Photographic Salon Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 15, no. 1 (Spring 2016) “The admiration one feels for something strange and uncanny”: Impressionism, Symbolism, and Edward Steichen’s Submissions to the 1905 London Photographic Salon by Kurt E. Rahmlow In August 1904, Alfred Horsley Hinton (1863–1908), editor of the British periodical Amateur Photographer and a founding member of the London-based art photography club the Brotherhood of the Linked Ring (hereafter Linked Ring), wrote to Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) to critique recent photographs by Edward Steichen (1879–1973). In the note, Hinton remarks, I admire Steichen’s work for myself but it is the admiration one feels for something strange and uncanny—I can’t think that such work is healthy or would in this country have a beneficial influence. Many, nay most, of his things were very well exhibited to his fellow artists in his studio. -

Information to Users

Alfred Stieglitz and the opponents of Photo-Secessionism Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Zimlich, Leon Edwin, Jr., 1955- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 21:07:09 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/291519 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

Nuances De Vie

NUANCES DE VIE: PHOTOGRAPHIC PRINTMAKING IN THREE MEDIUMS A Project Presented to the faculty of the Departments of Art and Design California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in SPECIAL MAJOR (Printmaking and Photography) by Valerie Wheeler SPRING 2012 © 2012 Valerie Wheeler ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii NUANCES DE VIE: PHOTOGRAPHIC PRINTMAKING IN THREE MEDIUMS A Project by Valerie Wheeler Approved by: ________________________________, Sponsor Sharmon Goff ________________________________, Committee Member Roger Vail ________________________________, Committee Member Nigel Poor _______________________ Date iii Student: Valerie Wheeler I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the project. ______________________________, Dean ________________ Chevelle Newsome, Ph.D. Date Office of Graduate Studies iv Abstract of NUANCES DE VIE: PHOTOGRAPHIC PRINTMAKING IN THREE MEDIUMS by Valerie Wheeler The goal of this special major in printmaking and photography was to bridge the two art forms through photo etching using classical and modern methods. In the process of learning large format photography, intaglio printmaking (photogravure), and non-etch intagliotype printing, I expanded the project to include platinum and palladium printing (making platinotypes and platino-palladiotypes). The continuity among the mediums rested upon the images, a few of which were printed in more than one medium. Landscapes, floral still-lifes, architecture, and a few portraits came together in a body of complementary work consisting of fifty-two images in four sizes. The thesis exhibition was installed and open for a week in the Robert Else Gallery; it included short technical labels to explain the three mediums. -

User Manual 2.3 MB

10M 25M 50M 75M 100M 10Y 25Y 50Y 75Y 100Y impact TM For EX-100A accessories and to see all of our lighting equipment, please visit our Web site. impactTM EX-100A Monolight www.impactstudiolighting.com INSTRUCTIONS Page 20 Page 1 (back cover) (front cover) 10M 25M 50M 75M 100M 10Y 25Y 50Y 75Y 100Y Thank you for your purchase of the Impact EX-100A Monolight. The One-Year Limited Warranty EX-100A Monolight is economical and lightweight, yet durable enough to give you many years of trouble-free service and enjoyment. Please read these operating instructions and safety precautions carefully before operating this equipment. Features • Three-stop range – full power to 1/8 power, steplessly • Built-in optical slave • Modeling lamp can be set to proportional or full power • Accepts Elinchrom-style reectors and head accessories (8-inch grid reector included) • Tactile, “grippy” feel that resists slipping, scratches, and shock damage • Commonly available 1/8˝ mini-plug sync input • Low 4.3V trigger voltage – safe for any camera’s circuitry Power Requirements This light comes in two models; one is designed for use with 110/120V AC power in the US and the other for 220V AC power in Europe. Neither model can be used outside of its native power region. Both are supplied with a three-prong, grounded plug. Do not attempt to defeat this safety feature. If necessary, use only grounded extension cords rated for six amps or greater. Warning There are no user-serviceable parts inside the unit. Only qualied service engineers should access the inside of the case (Danger – high-voltage parts inside).