By Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for Degree of in in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY of CALIFORN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamics September 6-4 1708.07400.Pdf

Dynamics of Current, Charge and Mass Bob Eisenberg Department of Applied Mathematics Illinois Institute of Technology USA Department of Physiology and Biophysics Rush University USA [email protected] Xavier Oriols Departament d’Enginyeria Electrònica, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, SPAIN [email protected] David Ferry School of Electrical, Computer, and Energy Engineering Arizona State University USA [email protected] Available on arXivhttps://arxiv.org/abs/1708.07400 at September 6, 2017 ABSTRACT Electricity plays a special role in our lives and life. The dynamics of electrons allow light to flow through a vacuum. The equations of electron dynamics are nearly exact and apply from nuclear particles to stars. These Maxwell equations include a special term, the displacement current (of a vacuum). The displacement current allows electrical signals to propagate through space. Displacement current guarantees that current is exactly conserved from inside atoms to between stars, as long as current is defined as the entire source of the curl of the magnetic field, as Maxwell did. We show that the Bohm formulation of quantum mechanics allows the easy definition of current without the mysteries of the theory of quantum measurements. We show how conservation of current can be derived without mention of the polarization or dielectric properties of matter. We point out that displacement current is handled correctly in electrical engineering by ‘stray capacitances’, although it is rarely discussed explicitly. Matter does not behave as physicists of the 1800's thought it did. They could only measure on a time scale of seconds and tried to explain dielectric properties and polarization with a single dielectric constant, a real positive number independent of everything. -

Leonardo Da Vinci and Perpetual Motion

Leonardo da Vinci and Perpetual Motion Allan A. Mills CELEBRATING LEONARDO DA VINCI CELEBRATING umankind has always sought to reduce the the same wheel, then the machine H ABSTRACT need for its own manual labor. Draught animals were one might turn “forever.” solution, but much more beguiling was the concept of ma- A number of empirical attempts Leonardo da Vinci illustrated chines that would work “by themselves,” with no obvious prime to achieve such a hydraulic chimera several traditional forms of mover [1]. Even in ancient times, it appears that at least two perhaps were made but went un- “perpetual-motion machine” in categories had been proposed: the self-pumping waterwheel recorded because they never worked. small pocket books now known and the mechanical overbalancing wheel. None of course Drawings and plans of self-pumping as the Codex Forster. He was well aware that these designs, worked, and as science and technology progressed it became wheels persisted into the 18th cen- based on waterwheel/pump apparent that any such device was theoretically impossible. tury and even into modern times combinations, mechanical However, before this understanding was fully achieved and as amusing artifacts of linear per- overbalancing hammers or became well known, many technologists and hopeful inven- spective [3]. Progress in the under- rolling balls, would not—and could not—work. tors [2] felt obliged to devote time to this hoary problem. standing of efficiency, friction and Among the former was Leonardo da Vinci. Well aware of the the conservation of energy gradu- futility of all suggestions for achieving “perpetual motion,” he ally vindicated the practical knowl- simply recorded—and refuted—ideas that were prevalent in edge that, no matter how ingenious, his time. -

The Museum of Unworkable Devices

The Museum of Unworkable Devices This museum is a celebration of fascinating devices that don't work. It houses diverse examples of the perverse genius of inventors who refused to let their thinking be intimidated by the laws of nature, remaining optimistic in the face of repeated failures. Watch and be amazed as we bring to life eccentric and even intricate perpetual motion machines that have remained steadfastly unmoving since their inception. Marvel at the ingenuity of the human mind, as it reinvents the square wheel in all of its possible variations. Exercise your mind to puzzle out exactly why they don't work as the inventors intended. This, like many pages at this site, is a work in progress. Expect revisions and addition of new material. Since these pages are written in bits and pieces over a long period of time, there's bound to be some repetition of ideas. This may be annoying to those who read from beginning to end, and may be just fine for those who read these pages in bits and pieces. Galleries The Physics Gallery, an educational tour. The physics of unworkable devices and the physics of the real world. The Annex for even more incredible and unworkable machines. Advanced Concepts Gallery where clever inventors go beyond the classical overbalanced wheels. New Acquisitions. We're not sure where to put these. Will They Work? These ideas don't claim perpetual motion or over-unity performance, nor do they claim to violate physics. But will they work? Whatever Were They Thinking? The rationale behind standard types of perpetual motion devices. -

Perpetual Motion Machines Math21a WATER MACHINE (1620)

Perpetual Motion Machines Math21a WATER MACHINE (1620). ABSTRACT. Is it possible to produce devices which produce energy? Such a machine is called a perpetual motion machine. It is also called with its Latin name perpetuum mobile. Water flowing down turns an pump which transports the water back up. There are many variants of this idea: a b electric motor which turns a generator whose electricity is LINE INTEGRALS. If F (x,y,z) is a vector field and γ : t 7→ r(t) is a curve, then W = F (r(t)) · r′(t) dt is Ra used to power the motor. In all of these ideas, there is called a line integral along the curve. The short-hand notation F · ds is also used. If F is a force field, Rγ a twist like some kind of gear or change of voltage which then W is work. confuses a naive observer. CLOSED CURVES. The fundamental theorem of line integrals assures that the line integral along a closed curve is zero if the vector field is a gradient field. The work done along a closed path is zero. In a physical context, this can be understood as energy conservation. BALL MACHINE (1997). ENERGY CONSERVATION. All physical experiments so far confirm that static force fields in our universe are of the form F = −∇U, where U is a function called the potential energy. If a body moves in this force The energy needed to lift the balls up is claimed to be field, its acceleration satisfies by Newton’s laws mx¨ = F (x). -

Zero-Point Fluctuations in Rotation: Perpetuum Mobile of the Fourth Kind Without Energy Transfer M

Zero-point fluctuations in rotation: Perpetuum mobile of the fourth kind without energy transfer M. N. Chernodub To cite this version: M. N. Chernodub. Zero-point fluctuations in rotation: Perpetuum mobile of the fourth kind without energy transfer. Mathematical Structures in Quantum Systems and pplications, Jun 2012, Benasque, Spain. 10.1393/ncc/i2013-11523-5. hal-01100378 HAL Id: hal-01100378 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01100378 Submitted on 9 Jan 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Zero-point fluctuations in rotation: Perpetuum mobile of the fourth kind without energy transfer∗ M. N. Chernoduby CNRS, Laboratoire de Math´ematiqueset Physique Th´eorique,Universit´eFran¸cois-Rabelais Tours, F´ed´eration Denis Poisson, Parc de Grandmont, 37200 Tours, France Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Gent, Krijgslaan 281, S9, B-9000 Gent, Belgium In this talk we discuss a simple Casimir-type device for which the rotational energy reaches its global minimum when the device rotates about a certain axis rather than remains static. This unusual property is a direct consequence of the fact that the moment of inertia of zero-point vacuum fluctuations is a negative quantity (the rotational vacuum effect). -

From Carlo Matteucci to Giuseppe Moruzzi

THE INTERNATIONAL MEETING : FROM CARLO MATTEUCCI TO GIUSEPPE MORUZZI : TWO CENTURIES OF EUROPEAN PHYSIOLOGY A SATELLITE OF THE 15 TH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF THE NEUROSCIENCES , ITALY, VILLA DI CORLIANO PISA 22-26 JUNE 2010 SPONSORING INSTITUTIONS Club d'histoire des neurosciences de la Société des Neurosciences, Paris. Galileo Museum, Firenze International Society for the History of Neurosciences. Università di Ferrara. Università di Pavia - Sistema Museale d’Ateneo. Université Pierre et Marie Curie – Paris. Université Diderot – Paris. Organizing Committee: Jean- Gaël Barbara, Cesira Batini, Michel Meulders, Marco Piccolino and Nicholas J. Wade. FINAL PROGRAM ND TUESDAY JUNE 22 VILLA DI CORLIANO 9:30-9:45 WELCOME BY THE HOSTS 9:45-10:15 HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION Alessandro Baldassari: The "Villa of Corliano " between art and history 10:15-11:45 OPENING SESSION : INTRODUCING MATTEUCCI AND MORUZZI : 10:15 Marco Piccolino, Ferrara. The electrophysiological work of Carlo Matteucci. 10:45 Michel Meulders Giuseppe Moruzzi: scientist and humanist. 11:15 COFFEE BREAK 11:45-12:15 Rita Levi-Montalcini, Roma. Giuseppe Moruzzi, a “formidable” scientist and a "formidable” man. 12:15 APERITIF AND LUNCH 15:00-16:00 MATTEUCCI AND HIS TIME 15:00 Simone Contardi and Mara Miniati, Firenze: Educating heart and mind: Vincenzo Antinori and the scientific culture in thee nineteenth century Florence. 15:30 Renato Mazzolini, Trento, Italy: Carlo Matteucci, between France and Italy. 16:00 COFFEE BREAK 16:15-18:30 THE BEGINNING AND DEVELOPMENT OF ELECTROPHYSIOLOGY 16:30 Nicholas J. Wade, Dundee, Stimulating the senses . 17:00 Marco Bresadola, Ferrara: Matteucci and the legacy of Luigi Galvani . -

HISTORICAL SURVEY SOME PIONEERS of the APPLICATIONS of FRACTIONAL CALCULUS Duarte Valério 1, José Tenreiro Machado 2, Virginia

HISTORICAL SURVEY SOME PIONEERS OF THE APPLICATIONS OF FRACTIONAL CALCULUS Duarte Val´erio 1,Jos´e Tenreiro Machado 2, Virginia Kiryakova 3 Abstract In the last decades fractional calculus (FC) became an area of intensive research and development. This paper goes back and recalls important pio- neers that started to apply FC to scientific and engineering problems during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Those we present are, in alphabet- ical order: Niels Abel, Kenneth and Robert Cole, Andrew Gemant, Andrey N. Gerasimov, Oliver Heaviside, Paul L´evy, Rashid Sh. Nigmatullin, Yuri N. Rabotnov, George Scott Blair. MSC 2010 : Primary 26A33; Secondary 01A55, 01A60, 34A08 Key Words and Phrases: fractional calculus, applications, pioneers, Abel, Cole, Gemant, Gerasimov, Heaviside, L´evy, Nigmatullin, Rabotnov, Scott Blair 1. Introduction In 1695 Gottfried Leibniz asked Guillaume l’Hˆopital if the (integer) order of derivatives and integrals could be extended. Was it possible if the order was some irrational, fractional or complex number? “Dream commands life” and this idea motivated many mathematicians, physicists and engineers to develop the concept of fractional calculus (FC). Dur- ing four centuries many famous mathematicians contributed to the theo- retical development of FC. We can list (in alphabetical order) some im- portant researchers since 1695 (see details at [1, 2, 3], and posters at http://www.math.bas.bg/∼fcaa): c 2014 Diogenes Co., Sofia pp. 552–578 , DOI: 10.2478/s13540-014-0185-1 SOME PIONEERS OF THE APPLICATIONS . 553 • Abel, Niels Henrik (5 August 1802 - 6 April 1829), Norwegian math- ematician • Al-Bassam, M. A. (20th century), mathematician of Iraqi origin • Cole, Kenneth (1900 - 1984) and Robert (1914 - 1990), American physicists • Cossar, James (d. -

Lesson Guide

SUGGESTED REFERENCES Perpetual Motion: The History of an Obsession Perpetual Motion W.J.G. Ord-Hume Kevin T. Kilty June 1998 Copyright 1992, 1999 All rights reserved Jim's Free Energy Page http://www.geocities.com/CapeCanaveral/Lab/1287/ NATIONAL SCIENCE EDUCATION STANDARDS Grades K - 4 and 5 - 8 Grades 5 - 8 Unifying Concepts and Processes Physical Science Evidence, models, and explanation Transfer of energy Form and function History and Nature of Science Science as Inquiry History of science VOLUME 16 ISSUE 7 Understanding about scientific inquiry PURSUING ENERGY ALTERNATIVES Physical Science Position and motion of objects SYNOPSIS Science and Technology Abilities of technological design What would you think of powering a car using a water fuel cell, a Understanding about science and technology home furnace powered by permanent magnets or a self driven elec- *Source: National Science Education Standards, 1996, National Academy Press tromagnetic engine with enough power to put a spacecraft into CREDITS orbit? This is all energy that we wouldn't have to pay for and Accreditation Board EDUCATOR ADVISORY PANEL for Engineering energy that wouldn't pollute the earth. Not only would free ener- and Fred Barch, M.S. Debra A. Murnan, B.A. Technology gy change our world but it would end our dependence on having to Rosemary Botting, M.S. John A. Murnan III, M.S. use so much of earth's fossil fuels. PRODUCTION CREDITS WRITER/PRODUCER: Megan Hantz In this edition of Science Screen Report for Kids, we will take a ASSOCIATE PRODUCER: Judi Sitkin look at the highly debated topic of free energy. -

Here Are Some Additional Notes I Was Jotting Down

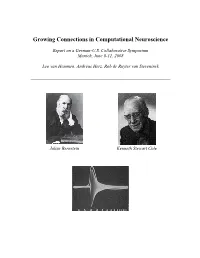

Growing Connections in Computational Neuroscience Report on a German-U.S. Collaborative Symposium Munich, June 8-11, 2008 Leo van Hemmen, Andreas Herz, Rob de Ruyter van Steveninck _____________________________________________________________ Julius Bernstein Kenneth Stewart Cole Cover pictures Portraits of Julius Bernstein and Kenneth Cole, and a key figure from a 1939 paper by Cole and Curtis. The figure demonstrates a dramatic increase in nerve membrane conductance during passage of an action potential. This result is a direct experimental confirmation of an essential feature of Bernstein’s theory of the action potential. Though their work was separated by a few decades, Cole’s studies in the United States were inspired by Bernstein’s work in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century. Cole, K.S. and Curtis, H.J., J Gen Physiol 22, 649-670 (1939) Acknowledgements The German-U.S. Collaborative Symposium, “Growing Connections in Computational Neuroscience,” was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF). 2 Contents Executive Summary............................................................................................................ 4 Introduction......................................................................................................................... 5 Scientific Background......................................................................................................... 5 Programmatic Background ................................................................................................ -

Carlo Matteucci, Giuseppe Moruzzi and Stimulation of the Senses: a Visual Appreciation

Archives Italiennes de Biologie, 149 (Suppl.): 18-28, 2011. Carlo Matteucci, Giuseppe Moruzzi and stimulation of the senses: a visual appreciation N.J. WADE School of Psychology, University of Dundee, UK A bstract The senses were stimulated electrically before speculations of the involvement of electricity in nerve transmis- sion received experimental support; it provided a novel means of defining the functions of the senses. Electrical stimulation was used by Charles Bell and Johannes Müller as a source of evidence for the doctrine of specific nerve energies because it resulted in the same sensations produced by natural or mechanical stimuli. The basis for understanding nerve transmission was provided by Luigi Galvani and Alesssandro Volta and elaborated by Carlo Matteucci and Emil du Bois-Reymond, both of whom maintained an interest in the senses. A century later, Giuseppe Moruzzi demonstrated how incoming sensory signals can be modulated by the reticular system. Key words Matteucci • Moruzzi • Nerve impulses • Reticular system • Senses Introduction of the senses. Indeed, the senses have provided an avenue to understanding the brain and its func- Giuseppe Moruzzi (1910-1986, Fig. 1) was born one tions since antiquity. However, sources of stimu- hundred years ago, and this significant anniversary has lation then available were limited: students could been marked by a conference held in Villa di Corliano, report on their experiences when stimulated natu- San Giuliano Terme (Fig. 1) from 22-26 June, 2010. rally, and they could relate them to their body parts. It also celebrated the distinguished physiologist Carlo Additional inferences could be drawn from disease Matteucci (1811-1868, Fig. -

Frank A.J.L. James *

— 149 — FRANK A.J.L. JAMES * Davy, Faraday and Italian Science ** An observer standing on Plymouth Hoe on the evening of 17 October 1813 would have seen a remarkable sight. This was a ship, sailing under a flag of truce, taking England’s leading chemist, Sir Humphry Davy,1 to France for a tour of the Continent. What was remarkable, of course, was that Britain and France had been engaged in a world war almost continuously for twenty years. The French govern- ment under the Emperor Napoleon (1769-1821) had provided him with a passport for a party to comprising himself, his wife and two servants to travel to France, to stay and to pass elsewhere in Europe.2 Although the Times had hoped that Davy would be interned in Verdun,3 the British government had no objection, and indeed facilitated the voyage as the Admiralty minuted to ‘Direct Transport Board to permit Sir Humphry & Lady Davy and 2 Servants to proceed in a Cartel to Mor- laix’.4 What all this suggests is that chemistry was not then seen by governments as playing a major role in the prosecution of war. Accompanying Davy were his wife Jane,5 whom he had married the previous * Royal Institution, 21 Albemarle Street, London, W1S 4BS, England. [email protected]. I wish to thank the Royal Institution, The Institution of Electrical Engineers and the Public Record Office (PRO) for permission to work on manuscripts in their possession. ** Relazione presentata al IX Convegno Nazionale di «Storia e Fondamenti della Chimica» (Modena, 25-27 ottobre 2001). -

Back Matter (PDF)

[ 229 • ] INDEX TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS, S e r ie s B, FOR THE YEAR 1897 (YOL. 189). B. Bower (F. 0.). Studies in the Morphology of Spore-producing Members.— III. Marattiaceae, 35. C Cheirostrobus, a new Type of Fossil Cone (Scott), 1. E. Enamel, Tubular, in Marsupials and other Animals (Tomes), 107. F. Fossil Plants from Palaeozoic Rocks (Scott), 1, 83. L. Lycopodiaceae; Spencerites, a new Genus of Cones from Coal-measures (Scott), 83. 230 INDEX. M. Marattiaceae, Fossil and Recent, Comparison of Sori of (Bower), 3 Marsupials, Tubular Enamel a Class Character of (Tomes), 107. N. Naqada Race, Variation and Correlation of Skeleton in (Warren), 135 P. Pteridophyta: Cheirostrobus, a Fossil Cone, &c. (Scott), 1. S. Scott (D. H.). On the Structure and Affinities of Fossil Plants from the Palaeozoic Ro ks.—On Cheirostrobus, a new Type of Fossil Cone from the Lower Carboniferous Strata (Calciferous Sandstone Series), 1. Scott (D. H.). On the Structure and Affinities of Fossil Plants from the Palaeozoic Rocks.—II. On Spencerites, a new Genus of Lycopodiaceous Cones from the Coal-measures, founded on the Lepidodendron Spenceri of Williamson, 83. Skeleton, Human, Variation and Correlation of Parts of (Warren), 135. Sorus of JDancea, Kaulfxissia, M arattia, Angiopteris (Bower), 35. Spencerites insignis (Will.) and S. majusculus, n. sp., Lycopodiaceous Cones from Coal-measures (Scott), 83. Sphenophylleae, Affinities with Cheirostrobus, a Fossil Cone (Scott), 1. Spore-producing Members, Morphology of.—III. Marattiaceae (Bower), 35. Stereum lvirsutum, Biology of; destruction of Wood by (Ward), 123. T. Tomes (Charles S.). On the Development of Marsupial and other Tubular Enamels, with Notes upon the Development of Enamels in general, 107.