Andrew Viterbi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bernard M. Oliver Oral History Interview

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt658038wn Online items available Bernard M. Oliver Oral History Interview Daniel Hartwig Stanford University. Libraries.Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford, California November 2010 Copyright © 2015 The Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. Note This encoded finding aid is compliant with Stanford EAD Best Practice Guidelines, Version 1.0. Bernard M. Oliver Oral History SCM0111 1 Interview Overview Call Number: SCM0111 Creator: Oliver, Bernard M., 1916- Title: Bernard M. Oliver oral history interview Dates: 1985-1986 Physical Description: 0.02 Linear feet (1 folder) Summary: Transcript of an interview conducted by Arthur L. Norberg covering Oliver's early life, his education, and work experiences at Bell Laboratories and Hewlett-Packard. Subjects include television research, radar, information theory, organizational climate and objectives at both companies, Hewlett-Packard's associations with Stanford University, and Oliver's association with William Hewlett and David Packard. Language(s): The materials are in English. Repository: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford, CA 94305-6064 Email: [email protected] Phone: (650) 725-1022 URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Information about Access Reproduction is prohibited. Ownership & Copyright All requests to reproduce, publish, quote from, or otherwise use collection materials must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94304-6064. Consent is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission from the copyright owner. -

Claude Elwood Shannon (1916–2001) Solomon W

Claude Elwood Shannon (1916–2001) Solomon W. Golomb, Elwyn Berlekamp, Thomas M. Cover, Robert G. Gallager, James L. Massey, and Andrew J. Viterbi Solomon W. Golomb Done in complete isolation from the community of population geneticists, this work went unpublished While his incredibly inventive mind enriched until it appeared in 1993 in Shannon’s Collected many fields, Claude Shannon’s enduring fame will Papers [5], by which time its results were known surely rest on his 1948 work “A mathematical independently and genetics had become a very theory of communication” [7] and the ongoing rev- different subject. After his Ph.D. thesis Shannon olution in information technology it engendered. wrote nothing further about genetics, and he Shannon, born April 30, 1916, in Petoskey, Michi- expressed skepticism about attempts to expand gan, obtained bachelor’s degrees in both mathe- the domain of information theory beyond the matics and electrical engineering at the University communications area for which he created it. of Michigan in 1936. He then went to M.I.T., and Starting in 1938 Shannon worked at M.I.T. with after spending the summer of 1937 at Bell Tele- Vannevar Bush’s “differential analyzer”, the an- phone Laboratories, he wrote one of the greatest cestral analog computer. After another summer master’s theses ever, published in 1938 as “A sym- (1940) at Bell Labs, he spent the academic year bolic analysis of relay and switching circuits” [8], 1940–41 working under the famous mathemati- in which he showed that the symbolic logic of cian Hermann Weyl at the Institute for Advanced George Boole’s nineteenth century Laws of Thought Study in Princeton, where he also began thinking provided the perfect mathematical model for about recasting communications on a proper switching theory (and indeed for the subsequent mathematical foundation. -

Marconi Society - Wikipedia

9/23/2019 Marconi Society - Wikipedia Marconi Society The Guglielmo Marconi International Fellowship Foundation, briefly called Marconi Foundation and currently known as The Marconi Society, was established by Gioia Marconi Braga in 1974[1] to commemorate the centennial of the birth (April 24, 1874) of her father Guglielmo Marconi. The Marconi International Fellowship Council was established to honor significant contributions in science and technology, awarding the Marconi Prize and an annual $100,000 grant to a living scientist who has made advances in communication technology that benefits mankind. The Marconi Fellows are Sir Eric A. Ash (1984), Paul Baran (1991), Sir Tim Berners-Lee (2002), Claude Berrou (2005), Sergey Brin (2004), Francesco Carassa (1983), Vinton G. Cerf (1998), Andrew Chraplyvy (2009), Colin Cherry (1978), John Cioffi (2006), Arthur C. Clarke (1982), Martin Cooper (2013), Whitfield Diffie (2000), Federico Faggin (1988), James Flanagan (1992), David Forney, Jr. (1997), Robert G. Gallager (2003), Robert N. Hall (1989), Izuo Hayashi (1993), Martin Hellman (2000), Hiroshi Inose (1976), Irwin M. Jacobs (2011), Robert E. Kahn (1994) Sir Charles Kao (1985), James R. Killian (1975), Leonard Kleinrock (1986), Herwig Kogelnik (2001), Robert W. Lucky (1987), James L. Massey (1999), Robert Metcalfe (2003), Lawrence Page (2004), Yash Pal (1980), Seymour Papert (1981), Arogyaswami Paulraj (2014), David N. Payne (2008), John R. Pierce (1979), Ronald L. Rivest (2007), Arthur L. Schawlow (1977), Allan Snyder (2001), Robert Tkach (2009), Gottfried Ungerboeck (1996), Andrew Viterbi (1990), Jack Keil Wolf (2011), Jacob Ziv (1995). In 2015, the prize went to Peter T. Kirstein for bringing the internet to Europe. Since 2008, Marconi has also issued the Paul Baran Marconi Society Young Scholar Awards. -

Channel Coding

1 Channel Coding: The Road to Channel Capacity Daniel J. Costello, Jr., Fellow, IEEE, and G. David Forney, Jr., Fellow, IEEE Submitted to the Proceedings of the IEEE First revision, November 2006 Abstract Starting from Shannon’s celebrated 1948 channel coding theorem, we trace the evolution of channel coding from Hamming codes to capacity-approaching codes. We focus on the contributions that have led to the most significant improvements in performance vs. complexity for practical applications, particularly on the additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) channel. We discuss algebraic block codes, and why they did not prove to be the way to get to the Shannon limit. We trace the antecedents of today’s capacity-approaching codes: convolutional codes, concatenated codes, and other probabilistic coding schemes. Finally, we sketch some of the practical applications of these codes. Index Terms Channel coding, algebraic block codes, convolutional codes, concatenated codes, turbo codes, low-density parity- check codes, codes on graphs. I. INTRODUCTION The field of channel coding started with Claude Shannon’s 1948 landmark paper [1]. For the next half century, its central objective was to find practical coding schemes that could approach channel capacity (hereafter called “the Shannon limit”) on well-understood channels such as the additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) channel. This goal proved to be challenging, but not impossible. In the past decade, with the advent of turbo codes and the rebirth of low-density parity-check codes, it has finally been achieved, at least in many cases of practical interest. As Bob McEliece observed in his 2004 Shannon Lecture [2], the extraordinary efforts that were required to achieve this objective may not be fully appreciated by future historians. -

Vector Quantization and Signal Compression the Kluwer International Series in Engineering and Computer Science

VECTOR QUANTIZATION AND SIGNAL COMPRESSION THE KLUWER INTERNATIONAL SERIES IN ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER SCIENCE COMMUNICATIONS AND INFORMATION THEORY Consulting Editor: Robert Gallager Other books in the series: Digital Communication. Edward A. Lee, David G. Messerschmitt ISBN: 0-89838-274-2 An Introduction to Cryptolog)'. Henk c.A. van Tilborg ISBN: 0-89838-271-8 Finite Fields for Computer Scientists and Engineers. Robert J. McEliece ISBN: 0-89838-191-6 An Introduction to Error Correcting Codes With Applications. Scott A. Vanstone and Paul C. van Oorschot ISBN: 0-7923-9017-2 Source Coding Theory.. Robert M. Gray ISBN: 0-7923-9048-2 Switching and TraffIC Theory for Integrated BroadbandNetworks. Joseph Y. Hui ISBN: 0-7923-9061-X Advances in Speech Coding, Bishnu Atal, Vladimir Cuperman and Allen Gersho ISBN: 0-7923-9091-1 Coding: An Algorithmic Approach, John B. Anderson and Seshadri Mohan ISBN: 0-7923-9210-8 Third Generation Wireless Information Networks, edited by Sanjiv Nanda and David J. Goodman ISBN: 0-7923-9128-3 VECTOR QUANTIZATION AND SIGNAL COMPRESSION by Allen Gersho University of California, Santa Barbara Robert M. Gray Stanford University ..... SPRINGER SCIENCE+BUSINESS" MEDIA, LLC Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gersho, A1len. Vector quantization and signal compression / by Allen Gersho, Robert M. Gray. p. cm. -- (K1uwer international series in engineering and computer science ; SECS 159) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4613-6612-6 ISBN 978-1-4615-3626-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4615-3626-0 1. Signal processing--Digital techniques. 2. Data compression (Telecommunication) 3. Coding theory. 1. Gray, Robert M., 1943- . -

Information Theory and Statistics: a Tutorial

Foundations and Trends™ in Communications and Information Theory Volume 1 Issue 4, 2004 Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief: Sergio Verdú Department of Electrical Engineering Princeton University Princeton, New Jersey 08544, USA [email protected] Editors Venkat Anantharam (Berkeley) Amos Lapidoth (ETH Zurich) Ezio Biglieri (Torino) Bob McEliece (Caltech) Giuseppe Caire (Eurecom) Neri Merhav (Technion) Roger Cheng (Hong Kong) David Neuhoff (Michigan) K.C. Chen (Taipei) Alon Orlitsky (San Diego) Daniel Costello (NotreDame) Vincent Poor (Princeton) Thomas Cover (Stanford) Kannan Ramchandran (Berkeley) Anthony Ephremides (Maryland) Bixio Rimoldi (EPFL) Andrea Goldsmith (Stanford) Shlomo Shamai (Technion) Dave Forney (MIT) Amin Shokrollahi (EPFL) Georgios Giannakis (Minnesota) Gadiel Seroussi (HP-Palo Alto) Joachim Hagenauer (Munich) Wojciech Szpankowski (Purdue) Te Sun Han (Tokyo) Vahid Tarokh (Harvard) Babak Hassibi (Caltech) David Tse (Berkeley) Michael Honig (Northwestern) Ruediger Urbanke (EPFL) Johannes Huber (Erlangen) Steve Wicker (GeorgiaTech) Hideki Imai (Tokyo) Raymond Yeung (Hong Kong) Rodney Kennedy (Canberra) Bin Yu (Berkeley) Sanjeev Kulkarni (Princeton) Editorial Scope Foundations and Trends™ in Communications and Information Theory will publish survey and tutorial articles in the following topics: • Coded modulation • Multiuser detection • Coding theory and practice • Multiuser information theory • Communication complexity • Optical communication channels • Communication system design • Pattern recognition and learning • Cryptology -

IEEE Information Theory Society Newsletter

IEEE Information Theory Society Newsletter Vol. 63, No. 3, September 2013 Editor: Tara Javidi ISSN 1059-2362 Editorial committee: Ioannis Kontoyiannis, Giuseppe Caire, Meir Feder, Tracey Ho, Joerg Kliewer, Anand Sarwate, Andy Singer, and Sergio Verdú Annual Awards Announced The main annual awards of the • 2013 IEEE Jack Keil Wolf ISIT IEEE Information Theory Society Student Paper Awards were were announced at the 2013 ISIT selected and announced at in Istanbul this summer. the banquet of the Istanbul • The 2014 Claude E. Shannon Symposium. The winners were Award goes to János Körner. the following: He will give the Shannon Lecture at the 2014 ISIT in 1) Mohammad H. Yassaee, for Hawaii. the paper “A Technique for Deriving One-Shot Achiev - • The 2013 Claude E. Shannon ability Results in Network Award was given to Katalin János Körner Daniel Costello Information Theory”, co- Marton in Istanbul. Katalin authored with Mohammad presented her Shannon R. Aref and Amin A. Gohari Lecture on the Wednesday of the Symposium. If you wish to see her slides again or were unable to attend, a copy of 2) Mansoor I. Yousefi, for the paper “Integrable the slides have been posted on our Society website. Communication Channels and the Nonlinear Fourier Transform”, co-authored with Frank. R. Kschischang • The 2013 Aaron D. Wyner Distinguished Service Award goes to Daniel J. Costello. • Several members of our community became IEEE Fellows or received IEEE Medals, please see our web- • The 2013 IT Society Paper Award was given to Shrinivas site for more information: www.itsoc.org/honors Kudekar, Tom Richardson, and Rüdiger Urbanke for their paper “Threshold Saturation via Spatial Coupling: The Claude E. -

2010 Roster (V: Indicates Voting Member of Bog)

IEEE Information Theory Society 2010 Roster (v: indicates voting member of BoG) Officers Frank Kschischang President v Giuseppe Caire First Vice President v Muriel M´edard Second Vice President v Aria Nosratinia Secretary v Nihar Jindal Treasurer v Andrea Goldsmith Junior Past President v Dave Forney Senior Past President v Governors Until End of Alexander Barg 2010 v Dan Costello 2010 v Michelle Effros 2010 v Amin Shokrollahi 2010 v Ken Zeger 2010 v Helmut B¨olcskei 2011 v Abbas El Gamal 2011 v Alex Grant 2011 v Gerhard Kramer 2011 v Paul Siegel 2011 v Emina Soljanin 2011 v Sergio Verd´u 2011 v Martin Bossert 2012 v Max Costa 2012 v Rolf Johannesson 2012 v Ping Li 2012 v Hans-Andrea Loeliger 2012 v Prakash Narayan 2012 v Other Voting Members of BoG Ezio Biglieri IT Transactions Editor-in-Chief v Bruce Hajek Chair, Conference Committee v total number of voting members: 27 quorum: 14 1 Standing Committees Awards Giuseppe Caire Chair, ex officio 1st VP Muriel M´edard ex officio 2nd VP Alexander Barg new Max Costa new Elza Erkip new Ping Li new Andi Loeliger new Ueli Maurer continuing En-hui Yang continuing Hirosuke Yamamoto new Ram Zamir continuing Aaron D. Wyner Award Selection Frank Kschischang Chair, ex officio President Giuseppe Caire ex officio 1st VP Andrea Goldsmith ex officio Junior PP Dick Blahut new Jack Wolf new Claude E. Shannon Award Selection Frank Kschischang Chair, ex officio President Giuseppe Caire ex officio 1st VP Muriel M´edard ex officio 2nd VP Imre Csisz`ar continuing Bob Gray continuing Abbas El Gamal new Bob Gallager new Conference -

Reflections on Compressed Sensing, by E

itNL1208.qxd 11/26/08 9:09 AM Page 1 IEEE Information Theory Society Newsletter Vol. 58, No. 4, December 2008 Editor: Daniela Tuninetti ISSN 1059-2362 Source Coding and Simulation XXIX Shannon Lecture, presented at the 2008 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Toronto Canada Robert M. Gray Prologue Source coding/compression/quantization A unique aspect of the Shannon Lecture is the daunting fact that the lecturer has a year to prepare for (obsess over?) a single lec- source reproduction ture. The experience begins with the comfort of a seemingly infi- { } - bits- - Xn encoder decoder {Xˆn} nite time horizon and ends with a relativity-like speedup of time as the date approaches. I early on adopted a few guidelines: I had (1) a great excuse to review my more than four decades of Simulation/synthesis/fake process information theoretic activity and historical threads extending simulation even further back, (2) a strong desire to avoid repeating the top- - - ics and content I had worn thin during 2006–07 as an interconti- random bits coder {X˜n} nental itinerant lecturer for the Signal Processing Society, (3) an equally strong desire to revive some of my favorite topics from the mid 1970s—my most active and focused period doing Figure 1: Source coding and simulation. unadulterated information theory, and (4) a strong wish to add something new taking advantage of hindsight and experience, The goal of source coding [1] is to communicate or transmit preferably a new twist on some old ideas that had not been pre- the source through a constrained, discrete, noiseless com- viously fully exploited. -

Curriculum Vitae of Thomas Kailath

Curriculum Vitae-Thomas Kailath Hitachi America Professor of Engineering, Emeritus Information Systems Laboratory, Dept. of Electrical Engineering Stanford, CA 94305-9510 USA Tel: +1-650-494-9401 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Fields of Interest: Information Theory, Communication, Computation, Control, Linear Systems, Statistical Signal Processing, VLSI systems, Semiconductor Manufacturing and Lithography. Probability Theory, Mathematical Statistics, Linear Algebra, Matrix and Operator Theory. Home page: www.stanford.edu/~tkailath Born in Poona (now Pune), India, June 7, 1935. In the US since 1957; naturalized: June 8, 1976 B.E. (Telecom.), College of Engineering, Pune, India, June 1956 S.M. (Elec. Eng.), Massachusetts Institute of Technology, June, 1959 Thesis: Sampling Models for Time-Variant Filters Sc.D. (Elec. Eng.), Massachusetts Institute of Technology, June 1961 Thesis: Communication via Randomly Varying Channels Positions Sep 1957- Jun 1961 : Research Assistant, Research Laboratory for Electronics, MIT Oct 1961-Dec 1962 : Communications Research Group, Jet Propulsion Labs, Pasadena, CA. He also held a part-time teaching appointment at Caltech Jan 1963- Aug 1964 : Acting Associate Professor of Elec. Eng., Stanford University (on leave at UC Berkeley, Jan-Aug, 1963) Sep 1964-Jan 1968 : Associate Professor of Elec. Eng. Jan 1968- Feb 1968 : Full Professor of Elec. Eng. Feb 1988-June 2001 : First holder of the Hitachi America Professorship in Engineering July 2001- : Hitachi America Professorship in Engineering, Emeritus; recalled to active duty to continue his research and writing activities. He has also held shorter-term appointments at several institutions around the world: UC Berkeley (1963), Indian Statistical Institute (1966), Bell Labs (1969), Indian Institute of Science (1969-70, 1976, 1993, 1994, 2000, 2002), Cambridge University (1977), K. -

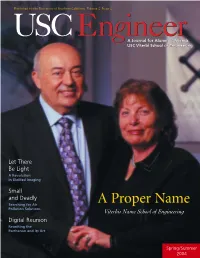

“USC Engineering and I Grew up Together,” Viterbi Likes to Say

Published by the University of Southern California Volume 2 Issue 2 Let There Be Light A Revolution in BioMed Imaging Small and Deadly A Proper Name Searching for Air A Proper Name Pollution Solutions Viterbis Name School of Engineering Digital Reunion Reuniting the Parthenon and its Art Spring/Summer 2004 One man’s algorithm changed the way the world communicates. One couple’s generosity has the potential to do even more. Andrew J. Viterbi: Presenting The University of Southern California’s • Inventor of the Viterbi Algorithm, the basis of Andrew and Erna Viterbi School of Engineering. all of today’s cell phone communications • The co-founder of Qualcomm • Co-developer of CDMA cell phone technology More than 40 years ago, we believed in Andrew Viterbi and granted him a Ph.D. • Member of the National Academy of Engineering, the National Academy of Sciences and the Today, he clearly believes in us. He and his wife of nearly 45 years have offered American Academy of Arts and Sciences • Recipient of the Shannon Award, the Marconi Foundation Award, the Christopher Columbus us their name and the largest naming gift for any school of engineering in the country. With the Award and the IEEE Alexander Graham Bell Medal • USC Engineering Alumnus, Ph.D., 1962 invention of the Viterbi Algorithm, Andrew J. Viterbi made it possible for hundreds of millions of The USC Viterbi School of Engineering: • Ranked #8 in the country (#4 among private cell phone users to communicate simultaneously, without interference. With this generous gift, he universities) by U.S. News & World Report • Faculty includes 23 members of the National further elevates the status of this proud institution, known from this day forward as USC‘s Andrew Academy of Engineering, three winners of the Shannon Award and one co-winner of the 2003 Turing Award and Erna Viterbi School of Engineering. -

Multi-Way Communications: an Information Theoretic Perspective

Full text available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1561/0100000081 Multi-way Communications: An Information Theoretic Perspective Anas Chaaban KAUST [email protected] Aydin Sezgin Ruhr-University Bochum [email protected] Boston — Delft Full text available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1561/0100000081 Foundations and Trends R in Communications and Information Theory Published, sold and distributed by: now Publishers Inc. PO Box 1024 Hanover, MA 02339 United States Tel. +1-781-985-4510 www.nowpublishers.com [email protected] Outside North America: now Publishers Inc. PO Box 179 2600 AD Delft The Netherlands Tel. +31-6-51115274 The preferred citation for this publication is A. Chaaban and A. Sezgin. Multi-way Communications: An Information Theoretic Perspective. Foundations and Trends R in Communications and Information Theory, vol. 12, no. 3-4, pp. 185–371, 2015. R This Foundations and Trends issue was typeset in LATEX using a class file designed by Neal Parikh. Printed on acid-free paper. ISBN: 978-1-60198-789-1 c 2015 A. Chaaban and A. Sezgin All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publishers. Photocopying. In the USA: This journal is registered at the Copyright Clearance Cen- ter, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use, or the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by now Publishers Inc for users registered with the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC).