Playing Senior Inter-County Gaelic Games: Experiences, Realities and Consequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Guide 2020

The Ladies Gaelic Football Association Est 1974 Official Guide 2020 6th April The Ladies Gaelic Football Association The Ladies Gaelic Football Association was founded in Hayes Hotel, Thurles, County Tipperary on 18 July 1974. Four counties, Offaly, Kerry, Tipperary and Galway attended the meeting. However, eight counties namely Cork, Kerry, Tipperary, Waterford, Galway, Roscommon, Laois and Offaly participated in the first official All Ireland Senior Championship of that year, which was won by Tipperary. Today, Ladies Gaelic Football is played in all counties in Ireland. It is also played in Africa, Asia, Australia, Britain, Canada, Europe, New Zealand, South America and the USA on an organised basis. It is imperative for our Association to maintain and foster our supportive contact with our International units. Our Association in Ireland must influence and help Ladies Football Clubs Internationally and share the spirit of home with those who are separated physically from their homes and to introduce those who have no connection with Ireland to the enjoyment of our sporting culture and heritage. The structure of the Ladies Gaelic Football Association is similar to that of the GAA with Clubs, County Boards, Provincial Councils, Central Council and Annual Congress. The National President is elected for one term of four years and shall not serve two consecutive terms. The Association was recognised by the GAA in 1982. In the early years of its foundation, the Association used the rules in the Official Guide of the GAA in conjunction with its own rules. The Ladies Gaelic Football Association decided at a Central Council meeting on 7th October 1985 to publish its own Official Guide. -

2020 Electric Ireland Higher Education GAA Championship Fixtures

2020 Electric Ireland Higher Education GAA Championship Fixtures 1 Please Note (General): • The following dates and fixtures for all competitions are indicative and subject to change. Full fixtures will be circulated later today. • All teams will be represented by numbered balls for draws. Seeds and unseeded teams listed in alphabetical order. • Result on the day if necessary in all knock-out fixtures. Two ten-minute periods of extra time, followed by a penalty taking competition if necessary. 2 Round 1 – Jan 12th 2020 First Team Named Has Home Advantage (A) NUIG v UCC (B) IT Tralee v IT Carlow (C) IT Sligo v UL (D) Athlone IT v Letterkenny IT (E) UCD v UU (F) Maynooth U v St Mary’s (G) DCU DE v Garda College (H) QUB v TU Dublin Quarter Finals – Jan 19th 2020 First team named has Home Advantage subject to Home and Away arrangement. (I) Winner of A v Winner of B (J) Winner of C v Winner of D (K) Winner of E v Winner of F (L) Winner of G v Winner of H Semi Finals – Jan 22nd 2020 Venue TBC (M) Winner of I v Winner of J (N) Winner of K v Winner of L Final – 29.01.20 – TBC Relegation Final – Jan 19th2020 - Neutral Loser of Fixture B v Loser of Fixture D 3 4 Groups: • 2 Groups of 3 teams, 2 group of 4 teams. • Top 2 teams in each group qualify for quarter finals. Group A 1. UL 2. DCU DE 3. Maynooth U 4. Trinity Group B 1. -

Gaa Master Fixtures Schedule

GAA MASTER FIXTURES SCHEDULE AN LÁR CHOISTE CHEANNAIS NA GCOMÓRTAISÍ 2017 Version: 21.11.2016 Table of Contents Competition Page Master Fixture Grid 2017 3 GAA Hurling All-Ireland Senior Championship 11 Christy Ring Cup 15 Nicky Rackard Cup 17 Lory Meagher Cup 19 GAA Hurling All-Ireland Intermediate Championship 20 Bord Gáis Energy GAA Hurling All-Ireland U21 Championships 21 (A, B & C) Hurling Electric Ireland GAA Hurling All-Ireland Minor Championships 23 Fixture Schedule Fixture GAA Hurling All-Ireland U17 Competition 23 AIB GAA Hurling All-Ireland Club Championships 24 GAA Hurling Interprovincial Championship 25 GAA Football All-Ireland Senior Championship 26 GAA Football All-Ireland Junior Championship 31 Eirgrid GAA Football All-Ireland U21 Championship 32 Fixture Fixture Electric Ireland GAA Football All-Ireland Minor Championship 33 GAA Football All-Ireland U17 Competition 33 Schedule AIB GAA Football All-Ireland Club Championships 34 Football GAA Football Interprovincial Championship 35 Allianz League 2017 (Football & Hurling) 36 Allianz League Regulations 2017 50 Extra Time 59 Half Time Intervals 59 GAA Master Fixture Schedule 2017 2 MASTER FIXTURE GRID 2017 Deireadh Fómhair 2016 Samhain 2016 Nollaig 2016 1/2 (Sat/Sun) 5/6 (Sat/Sun) 3/4 (Sat/Sun) AIB Junior Club Football Quarter-Final (Britain v Leinster) Week Week 40 Week 45 Week 49 8/9 (Sat/Sun) 12/13 (Sat/Sun) 10/11 (Sat/Sun) AIB Senior Club Football Quarter-Final (Britain v Ulster) 10 (Sat) Interprovincial Football Semi-Finals Connacht v Leinster Munster v Ulster Interprovincial -

2013 Annual Congress Papers

1 An Chomhdháil Bhliantúil 2013 Contents 1 Clár 2 Teachtaireacht ón Uachtarán 4 Highlights from 2012 6 Tuairisc an Ard Stiúrthóra Sealadach 27 Provincial and Overseas Reports 52 Sub-Committees Reports 67 Reports from Camogie Representatives on GAA Sub-Committees 71 Report and Financial Statements 82 Motions 90 Torthaí na gComórtas 2012 91 Principle Dates 2013 92 Soaring Stars 2012 93 All Stars 2012 An Chomhdháil Bhliantúil 2013 1 An Chomhdháil Bhliantúil 2013 22 agus 23 Márta 2013 Hotel Wesport, Mayo Dé hAoine, 22 Márta 4.30 - 5.30pm Integrated Fixtures Workshop and ‘Camogie For All’ Workshop 6.00 - 7.30pm Registration 8.00pm Fáilte 8.15pm Adoption of standing orders 8.20pm Minutes of Congress 2012 8.30pm Affiliations motion presentation – Q&A round table clarifications 9.00pm Reports: Provincial, International Units, National Education Councils, Sub-committees 10.00pm Críoch Dé Sathairn, 23 Márta 8.45am Registration 9.15am Financial Accounts 9.40am Ard Stiúrthóir’s Report 10.15am Address from John Treacy, CEO Irish Sports Council 10.50am Break 11.20am Consideration of motions 12.30am Address by Uachtarán Aileen Lawlor 1.00pm Lón 2.00pm Consideration of motions 3.50pm Venue for Congress 2014 4.00pm Críoch 7.30pm Mass 8.00pm Congress Dinner BUANORDAITHE (Standing Orders) An Cumann 1. The proposer of a resolution or an amendment may speak for five minutes. Camógaíochta 2. A delegate to a resolution or an amendment may not exceed three minutes. Ardchomhairle, 3. The proposer of a resolution or an amendment may speak a second time for three minutes before a vote is taken. -

Annual Report

Introduction GAA Games Development 2014 Annual Report for the Irish Sports Council GAA Games Development 2014 A Annual Report for the Irish Sports Council @GAAlearning GAALearning www.learning.gaa.ie Foreword Foreword At a Forum held in Croke Park in June 2014 over 100 young people aged 15 – 19 were asked to define in one word what the GAA means to them. In their words the GAA is synonymous with ‘sport’, ‘parish’, ‘club’, ‘family’, ‘pride’ ‘passion’, ‘cultúr’, ‘changing’, ‘enjoyment’, ‘fun’, ‘cairdeas’. Above all these young people associated the GAA with the word ‘community’. At its most fundamental level GAA Games Development – through the synthesis of people, projects and policies – provides individuals across Ireland and internationally with the opportunity to connect with, participate in and contribute as part of a community. The nature and needs of this unique community is ever-changing and continuously evolving, however, year upon year GAA Games Development adapts accordingly to ensure the continued roll out of the Grassroots to National Programme and the implementation of projects to deliver games opportunities, skill development and learning initiatives. As recognised by Pierre Mairesse, Director General for Education and Culture in the European Commission, these serve to ‘go beyond the traditional divides between sports, youth work, citizenship and education’. i Annual Report for the Irish Sports Council. GAA Games Development 2014 2014 has been no exception to this and has witnessed some important milestones including: 89,000 participants at Cúl Camps, the introduction of revised Féile competitions that saw the number of players participating in these tournaments increase by 4,000, as well as the first ever National Go Games Week - an event that might have seemed unlikely less than a decade ago. -

Camogie Development Plan 2019

Camogie Development Plan 2019 - 2022 Vision ‘an engaged, vibrant and successful camogie section in Kilmacud Crokes – 2019 - 2022’ Camogie Development Ecosystem; 5 Development Themes Pursuit of Camogie Excellence Funding, Underpinning everything we do: Part of the Structure & ➢ Participation Community Resources ➢ Inclusiveness ➢ Involvement ➢ Fun ➢ Safety Schools as Active part of the Volunteers Wider Club • A player centric approach based on enjoyment, skill development and sense of belonging provided in a safe and friendly environment • All teams are competitive at their age groups and levels • Senior A team competitive in Senior 1 league and championship • All players reach their full potential as camogie players • Players and mentors enjoy the Kilmacud Crokes Camogie Experience • Develop strong links to the local schools and broader community • Increase player numbers so we have a minimum of 40 girls per squad OBJECTIVES • Prolong girls participation in camogie (playing, mentoring, refereeing) • Minimize drop-off rates • Mentors coaching qualifications are current and sufficient for the level/age group • Mentors are familiar with best practice in coaching • Well represented in Dublin County squads, from the Academy up to the Senior County team • More parents enjoying attending and supporting our camogie teams Milestones in Kilmacud Crokes Camogie The Camogie A dedicated section was nursery started U16 Division 1 Teams went from started in 1973 by County 12 a side to 15 a Promoted Eileen Hogan Champions Bunny Whelan side- camogie in -

PRESENTED in ASSOCIATION with Mcaleer & RUSHE and O'neills

LOOKING FORWARD TO THIS YEAR’S NATIONAL LEAGUES PRESENTED IN ASSOCIATION WITH McALEER & RUSHE AND O’NEILLS he GAA is central to Tyrone and the people 3 in it. It makes clear statements about Who Working as a Team we are and Where we’re from, both as Tindividuals and as a community. The Red CLG Thír Eoghain … Hand Fan is now a fixed part of the lead-in to the working to develop TYRONE GAA & OUR SPONSORS new Season for our young people. Read it. Enjoy it. and promote Gaelic But above all, come along to the Tyrone games and games and to foster be part of it all. ‘Walk into the feeling!’ local identity and After another McKenna Cup campaign culture across Tyrone that we can take many positives from, we’re approaching the Allianz League in It’s a very simple but very significant a very positive mind-set. We’ve always fact that the future of Tyrone as a prided ourselves on the importance County and the future of the GAA we place on every game and this year’s in our County, currently sit with Allianz League is no exception. the 20,000 pupils who attend our schools. These vitally important young Tyrone people are the main focus of the work we all do at Club, School and County level. Tyrone GAA is about providing a wholesome focus for our young people, about building their sense of ‘Who they are’ and ‘Where they are from’ and about bolstering their self-esteem and personal contentment. We’re producing this Fanzine for all those pupils … and also, of course, for their parents, guardians, other family members and, very importantly, their teachers. -

GAA Annual Report 1-256

REPORT OF THE ARD STIÚRTHÓIR 8 AN CHOMHDÁIL BHLIANTÚIL 2018 2017 TUARASCÁIL AN ÁRD STIÚRTHÓRA AGUS CUNTAIS AIRGID 9 REPORT OF THE ARD STIÚRTHÓIR INTRODUCTION “In the All-Ireland hurling championship, the new order well and truly replaced the old” The outstanding achievement in the GAA sporting in the All-Ireland quarter-fnal. All of which made their year was undoubtedly Dublin’s third victory in-a-row in semi-fnal defeat to Dublin the more disappointing. the All-Ireland Senior Football Championship. Only an The success of the Kerry minor team should not be exceptional team can reach such a consistently high overlooked; their 2017 All-Ireland victory was their standard, so there can be no question about the merit fourth title in-a-row, an exceptional achievement that of Dublin’s victory in 2017. When the stakes were at augurs well for the future of their senior team as it their highest and the pressure at its greatest, Dublin seeks to overcome Dublin’s current superiority. again proved themselves to be true champions. And yet the margin of fnal victory in September was as In the All-Ireland hurling championship, the new order small as it could be, not just in the fnal score but in well and truly replaced the old. It was not simply that the whole ebb and fow of what was an extraordinarily Kilkenny failed to reach even the Leinster fnal, but tense fnal against Mayo. So close was the encounter that the two other titans of hurling, Tipperary and that it was easy afterwards to imagine scenarios – a Cork, were also toppled in their respective All-Ireland chance not missed, a diferent option taken – in which semi-fnals. -

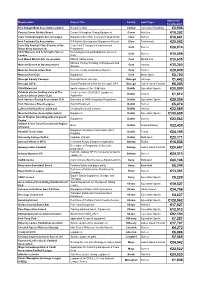

Grid Export Data

Amount to Organisation Project Title County Sport Type be allocated Irish Dragon Boat Association Limited Buoyancy Aids Carlow Canoeing / Kayaking €3,998 County Cavan Athletic Board Cavan / Monaghan Timing Equipment Cavan Athletics €19,302 Clare Schoolboy/girls Soccer League Equipment for CSSL newly purchased facility Clare Soccer €18,841 Irish Taekwon-Do Association ITA Athlete Development Equipment Project Clare Taekwondo €20,042 Cork City Football Club (Friends of the Cork City FC Equipment Improvement Cork Soccer Rebel Army Society Ltd) Programme €28,974 Cork Womens and Schoolgirls Soccer Increasing female participation in soccer in Cork Soccer League Cork €10,599 Irish Mixed Martial Arts Association IMMAF Safety Arena Cork Martial Arts €10,635 Munster Hockey Funding for Equipment and Munster Branch of Hockey Ireland Cork Hockey Storage €35,280 Munster Cricket Union CLG Increase facility standards in Munster Cork Cricket €29,949 Munster Kart Club Equipment Cork Motor Sport €2,700 Donegal County Camogie Donegal Senior camogie Donegal Camogie €1,442 Donegal LGFA Sports Equipment & Kits for Donegal LGFA Donegal Ladies Gaelic Football €8,005 ChildVision Ltd sports equipment for ChildVision Dublin Equestrian Sports €30,009 Cricket Leinster (trading name of The Cricket Leinster 2020/2021 Equipment Dublin Cricket Leinster Cricket Union CLG) Application €1,812 Irish Harness Racing Association CLG Extension of IHRA Integration Programme Dublin Equestrian Sports €29,354 Irish Homeless Street Leagues Sports Equipment Dublin Soccer €5,474 Leinster -

CLG ULADH an Chomhdháil Bhliantúíl 2016

#WeAreUlsterGAA CLG ULADH An Chomhdháil Bhliantúíl 2016 TUARASCÁIL AN RÚNAÍ #WeAreUlsterGAA Tuarascáil an Rúnaí A Chairde, Pension’ requirements. At the end of supporters for their continued the year Comhairle Uladh had worked attendances at our games. The The progress of the Association is its way through the many complex substantial reduction in the value of onwards, upwards and at times very legal aspects that apply to employees, the Euro has had significant impacts slowly before us. The performance Comhairle Uladh and to the law of the on transfers in the euro and sterling of our Counties is generally good but land. This has witnessed the ongoing transactions. The Marketing of our the matter of hurling does need to be of the requirements being more and games has been very substantially reviewed and renewed. more regulated and everything from maintained and this in turn has seen VAT to Pensions are placing greater a continued increase in online sales of When the past year is examined there responsibility on organisations like tickets for games ensuring that those are many aspects that are admirable ourselves. The ongoing inputs relating attending our games can pre - purchase as we are very competitive in football, to the proposed redevelopment of tickets either through our units or via but we do need to adhere to the Casement Park are also quite time tickets.ie or through outlets of the One Club One Association ideal. We consuming; the increased attendances, Musgrave Group. We are now starting welcome and admire the success greater input into funding for to see the growth in the wider economy of the Tír Eoghain Under 21 football projects and the stringent budgetary and we shall continue to market our team in winning the All-Ireland requirements places further obligations games, continue to work for the Championship. -

Na Fianna Nuacht 160318

Na Fianna Nuacht The Sports Forum Event was set up to provide funding to teams for the year ahead with all of the profits to be distributed to teams. The organizing committee started the process back in November with the intention of putting on a show with a high quality line up in a high quality setting that would appeal to members and non-members alike. A total of nine teams from juvenile to adult participated who would share in the profits from selling tickets and adverts as well as auction and raffle. As a club we are fortunate to have such a diverse group of members and the show would not have been possible without the help of our very own MC Shane Coleman from Newstalk, Dessie Farrell, John Horan, Jonny Cooper as well as past members Kieran McGeeney and Kenny Cunningham, and behind the scenes Senan Connell, Karl Donnelly, Neil Mulhern, Tom Dowd and Stephen Behan helped with the production. The night kicked off with Barry Murphy’s alter ego Gunther Grun providing the entertainment and it was clear to see why he is recognised as one of the 10 Kings of Irish Comedy over the last 20 years by Hot Press. Next up were Shane Coleman with Anna Geary, Kenny Cunningham and Shane Horgan. Each of the panel shared some great stories and delved into a variety of topics keeping the audience suitably entertained. After the break we were treated to some more fun from Barry Murphy, this time MC Shane Coleman being the subject matter. Following this and allowing Shane some respite from Barry’s attentions, Shane welcomed on stage Jonny Cooper and Kieran McGeeney who gave us insights into coaching and what it takes to play at the top level in sport. -

MIC Annual Report 2015-2016 English 2.Pdf

2015 2016 ANNUAL REPORT www.mic.ul.ie fl MIC ANNUAL REPORT 15-16 PAGE 2 Professor Peadar Cremin President of Mary Immaculate College 1999 - 2011 In 1999 Professor Cremin was appointed as the first lay President of the College in 101 years. Over the term of his presidency, the College community expanded dramatically with, by the time of his retirement in 2011, over 3,000 students enrolled on 30 different academic programmes at under - graduate, postgraduate and doctoral levels. Professor Cremin contributed hugely to the development of the College, including the growth in student numbers, the introduction of new academic programmes and the physical transformation of the campus. He oversaw the completion of a major capital investment programme to a total of €40 million, resulting in the provision of class-leading facilities that include Tailteann, our award winning multi-purpose sports complex, and TARA – a teaching and recreational building. Professor Cremin was also the driving force behind the establishment of Limerick's premier theatre venue, the very successful 510-seat Lime Tree Theatre. Throughout his long and exceptional career in Mary Immaculate College, Peadar-as he was always known - made an indelible mark in three respects particularly. He was a natural leader, as likely in company to make the first foray into tale or rhyme as he was, amongst colleagues, to set an ambitious vision and marshall all and sundry towards its realisation. Secondly, with remarkable tenacity, and in the face of towering odds, he succeeded in orchestrating the physical transformation of the campus by wrestling funds from an economy entering free-fall in mid-2008.